David Hewes and His Steam Paddy Works

Historical Essay

by David D. Schmidt, 2019

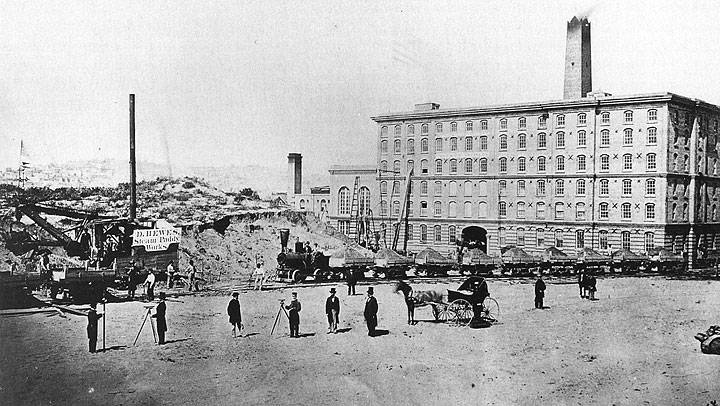

The "Hewes Steam Paddy Works" at left side of photo shows how the sand dunes that once dominated the South of Market were leveled, filling in the once ubiquitous fresh water ponds. 'Paddy' refers derogatorily to the Irish laborers who were replaced by the steam shovel. The building is Gordon's Sugar Works at 8th and Harrison.

Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco, CA

San Francisco exploded in all directions during the Gold Rush, despite huge sand dunes that covered the future Market Street and rocky hills on the south, north and west of its original nucleus around Portsmouth Square in today’s Financial District. One clever immigrant, David Hewes, was hired by the owner of a large lot at the corner of Stockton and O’Farrell Streets to remove a sand hill and level it. Hewes bought a shovel and a wheelbarrow and hired a Chinese laborer to do the work. He quickly scaled up to 20 Chinese workers sweating 12 hours a day for two dollars an hour. The unwanted sand and soil went to fill nearby low-lying lots, where landowners needed it to raise the ground to street level – and paid him again to get it. When the job was finished, he had netted a profit of $600 – equivalent to more than $10,000 today.

Gold Rush San Francisco, hillier than it is today, was filled with such jobs, and Hewes became the go-to guy for grading and levelling, getting contracts from the city government – paid for by sales of water lots – to level streets. In 1852 Hewes and James Cunningham brought a steam shovel, rail cars, two steam “pony” locomotives, and two miles of rails by ship from Worcester, Mass. With this earth-moving system they commenced levelling nearly eight square miles of sand hills and filling the bay on an industrial scale. The steam shovel loaded the cars with sand, and the trains took it down to the wharves, where workers shoveled it onto the “water lots.” The operation had more than 100 laborers toiling six days a week.

By this time, “The piling across the bay and the filling were constantly going on. No sooner was a water lot piled and capped than up sprang a [wood] frame building upon it; no sooner was the hollow beneath filled than the house of wood was destroyed, and replaced by some elegant brick or granite structure.” By 1853 there were “12 large wharves, besides nearly as many small cross ones. About 2 ½ miles of streets and wharves [were] made on piles over the water.”(1) Each of these wharves and cross-wharves made it possible to transport cartloads or train car loads of sand to any of the water lots, whose owners paid to fill them in, creating high-priced real estate. Although San Francisco had no gold deposits, its bay mud, in effect, was being transformed into gold.

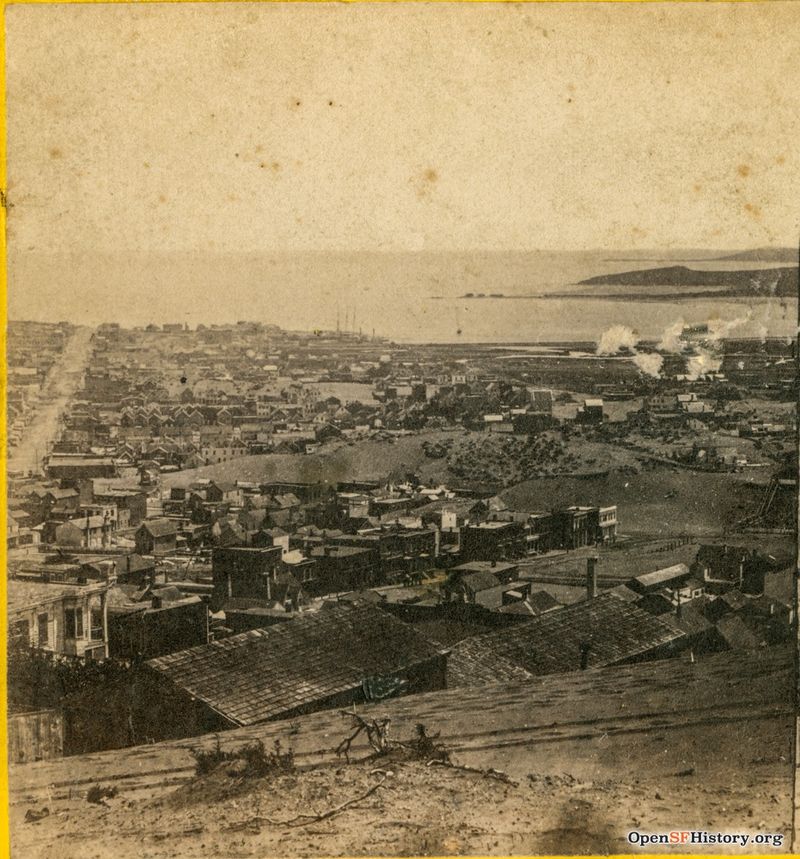

Hewes got a city government contract to level Market Street from Third to Tenth Streets, which required him to take down a 200-foot-high sand hill at Market and Third. The dune shrank as the endless parade of rail cars extended the shoreline eastward into the bay.

Charles Leander Weed took this photo from approximately Sacramento and Taylor near the top of Nob Hill in 1858, looking south/southeast. The large sand dune in the middle of the image blocked Market at 3rd Street until Hewes was hired to take it down.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp24.0149a

Others with less capital also got into the business. Julia L. Hare, who had lived in San Francisco as a girl in 1853, recalled that “As we stood out on the street during each week day, what we saw most often passing were the water carts [which sold fresh water by the bucket, since there were no wells or piped water], or stronger carts hauling sand from the hills to the bay. So the bay was getting filled under and about the wharves.”(2)

Hewes called his sand-hauling system the “Steam Paddy Works.” “Paddy” referred to the Gold Rush city’s numerous Irishmen, refugees from the Potato Famine in Ireland, some of whom were named “Patrick,” and commonly called “Paddies.” The Steam Paddy was said to do the work of 20 human Paddies. Actually the machine did much more. In a single bite it scooped up a cubic yard of sand weighing 1 ½ tons, more than twice what a single-horse cart could move. The Steam Paddy could move up to 2,500 tons in a single day. In the 1860s there were two Steam Paddies constantly at work in San Francisco. Hewes and his exhausted workers (they went on strike in 1860 to reduce their 12-hour work day to 10) filled in hundreds of acres of Yerba Buena Cove, plus a smaller cove at North Beach (today a misnomer because the former beach is landlocked), and finally Mission Bay (a much larger inlet, now a neighborhood south of the Bay Bridge), all without Hewes himself ever lifting a shovel. The steam paddy made him so wealthy that when the Transcontinental Railroad was completed at Promontory Point, Utah on May 10, 1869, Hewes donated the final railroad tie – made from a California laurel tree – and the final spike of pure gold.

Notes

1. Soule, Frank, John H. Gihon, MD, and James Nisbet, The Annals of San Francisco (originally published in 1856, 1966 edition by Lewis Osborne, Palo Alto), pp. 414, 494.

2. Julia L. Hare, reminiscences, California State Library

From a forthcoming book by David D. Schmidt, San Francisco Bay Area: The Environmental History. For more information, contact the author at davidnaturesf@gmail.com.