Carol Seajay, Old Wives Tales and the Feminist Bookstore Network

Historical Essay

by Elizabeth Sullivan

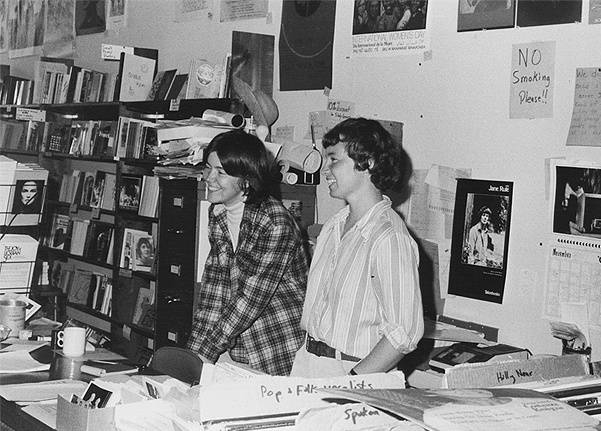

Staffers cavort in front of Old Wives Tales, c. early 1980s.

Photographer unknown, via Facebook

Interior of Old Wives Tales bookstore, 1980s.

"I came to San Francisco with a ray of hope about living life as a lesbian woman."

Starting from the early 1970s, Carol Seajay knows intimately the history of women's bookstores in San Francisco. In addition to her work with Full Moon in San Francisco and A Woman's Place in Oakland, she is a co-founder of Old Wives Tales, the women's bookstore on Valencia Street that closed in 1995. She is also a founder of the Feminist Bookstore Network and Newsletter, which is going stronger than ever in 1997.

Carol Seajay arrived in San Francisco from school in Michigan in December of 1973. The first connection she made with the women's and lesbian culture that she was seeking here was through a flyer in a women's bathroom in the Main Library. It advertised a Women's Coffeehouse and Bookstore, at a place called the Full Moon. The early seventies saw a concerted effort on the part of feminists to cultivate an alternative culture--a world based on feminist values and the celebration of the power of women. Posting announcements in women's bathrooms was a favorite technique, the perfect expression of solidarity between women.

Seajay already had an affinity for books by and for lesbians. She had attended the Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo, and there she read early lesbian classics like Anne Aldridge, Beebo Brinker, The Price of Salt--anything about lesbians that she could find. But none had a happy ending. She said, "I just never read the last chapter--that was the advice everyone gave you." Early lesbian novels available in the late sixties inevitably ended in double suicides or dramatic conversions. A friend gave her a grant of $50 a month to write a lesbian novel with a happy ending. For her last year of school Seajay worked on the novel and at a job doing abortion counseling.

January 22, 1973 brought a huge change for women in the United States with the supreme court ruling on abortion, Roe vs. Wade. After the decision, according to Seajay, there was a race between Planned Parenthood and the more radical activists for funding to provide health care for women. "I'd be willing to bet that 2/3 of those active in the abortion movement at the time were lesbians," Seajay said. "There is a clear connection between freedom from pregnancy and the freedom to be a lesbian, the freedom to make your own choices about what you do with your body." But one woman in the health care community used a strategy of outing radical feminists as lesbian (there were not many out lesbians at the time) in order to secure a job for herself. In those days outing meant certain exclusion, and Seajay was an early casualty.

She worked for a while as a cocktail waitress, saved her money, and bought a 2-cylinder Honda motorcycle for $400. She left Michigan and drove the Honda to San Francisco. At the time, Seajay said, the choice was strictly New York or San Francisco for lesbian and gay people. But in New York, people did the bars at night, slept all day and jumped off a bridge when they got to be 30. "I came to San Francisco with a ray of hope about living life as a lesbian woman," she said. San Francisco offered acceptance, companionship, and even celebration of being a lesbian or a gay man. That vision, of children and friends all knowing and of growing old while being out, was the promise San Francisco held out for Seajay. This was also true for many other lesbians and gay men who began streaming here from all across the country in the late 60s and 70s.

Arriving in San Francisco

When Seajay was first in San Francisco, there was already a very developed, very intense, lesbian scene. It was a vibrant community. Seajay had read Lyon and Martin's The Ladder back in Michigan. A subscriber had to sign a slip swearing she was 21, so Seajay borrowed it from a friend. "I remember thinking, there are enough lesbians [in San Francisco] to publish a magazine!" When she got to San Francisco and was first getting involved in the scene here, "it was electric, every night, there were at least two very exciting things you could do--you had to choose because there was so much.

"There was a sense then, that if we wanted to turn over patriarchy--we could." In that spirit, with possibilities opening to women in such dramatic new ways, Seajay decided that she wanted to be an electrician. She signed up with a women's trade group to be trained once she passed the union admission tests, but the waiting list for training was 2 1/2 years, due to the bad economy at the time. So, while waiting she went to a local free school operating at the time and took classes like, Lesbianism, Socialism and Feminism and Criticism and Self-criticism. This deepened her love of reading as well as her lesbian identity.

Full Moon Cafe and Bookstore, the bookstore on the flyer in the Main Library women's bathroom, was on 18th Street. The collective, which Seajay quickly joined, spent all spring getting the store together. They laid a new cement floor. They also handled all the drainage and plumbing themselves. "It was a dyke thing to do everything ourselves," Seajay said. "So if you open a dyke coffeehouse, and it needs a new cement floor, you learn to lay cement floors."

The side room of the cafe held books (it was about the size of a Murphy bed), and that was the bookstore. The collective's attitude about most things was always, "Why ask? We'll just do it." Unfortunately that meant that they never got licenses for any of the cabarets or gatherings held at Full Moon. In 1977 they were closed because they didn't have a cabaret license. Upstairs neighbors complained and the Full Moon collective lost their lease.

Seajay got a job with the state where she coded questionnaires as an assistant statistician, and read her homework for free school at lunch time. "In those days," she recalled, "for an hour of minimum wage work a person could afford to buy six mass market books. Nowadays they could afford maybe 1/2 maybe 2/3 of one book. But there was a very socialist feel to San Francisco then, people had way less stuff." After saving up some money, she went to India for four months. When she got back, she moved in next door to a woman from her socialism class named Gretchen Milne (now Forest), who was one of the women who started A Woman's Place, a feminist bookstore in Oakland.

San Francisco Lesbian Literary Scene

It was the mid seventies, the recession, and Seajay's new neighbor, Gretchen Milne, was living on unemployment and working on A Woman's Place bookstore. Seajay went down to check it out, there were two whole shelves of lesbian books. "I was astounded. After I finished reading all the lesbian books I started reading Black women's work. It was similarly woman-identified and very powerful. Ann Petry, The Street, Toni Morrison." Everything she could want. She started volunteering, riding the bus to Oakland once or twice a week to sit on the floor and read every last book.

At the time, Seajay recalled, lots of lesbian ideas were actually coming out in poetry. People were starting to do anthologies, self-published, staple-bound. Poetry became very important to San Francisco's lesbian community. The Women's Press Collective was started and Judy Grahn and Wendy Cadden were making all the books themselves. There was even a women's distribution company for women's newspapers!

Paula Wallace was a worker at A Woman's Place with Seajay at this time and she and Seajay were also lovers. They decided to start a San Francisco women's bookstore together. So they applied for a loan from the very friendly San Francisco Feminist Federal Credit Union. At the time, there were three people on the loan committee. A feminist bookstore owner from Hayward was one, and a lesbian feminist published poet was another. This illustrates the success of feminist organizing in the seventies. When the women's bookstore project needed a loan, they went to the Feminist Credit Union. After applying, Seajay went off to the First National Women in Print Conference.

Ruth Mahaney and Molly Martin, interviewed in late 2018 and early 2019 respectively, remember early encounters with feminist bookstores and lesbian printing.

Video: Shaping San Francisco

Beginning of Feminist Bookstore News

The First National Women in Print Conference happened thanks to the organizing of June Arnold and Daughters Publishers. No one else from A Woman's Place could go (partly because there was the I Hotel crisis at that time) so Seajay got in her car and went herself. "It was a traveling time," Seajay recalled, "people just got in cars and drove where they wanted to go. That's how this literature got around. We drove it. People didn't have to worry as much about money, or keeping jobs, there were ways to get by.

"You see, the baby boom left school and there weren't any jobs for us. We weren't necessary. But we said, good, we don't want your jobs anyway. In Canada at the time they were experiencing the same thing, and the government encouraged kids to travel around, see the country instead of work; they sponsored crash pads all over."

It was a week long conference in Nebraska (picked because it was equidistant from the coasts and everybody was driving), and it was incredible, according to Seajay. 18-20 women's bookstores and 180 women at a beautiful Campfire girl camp. It was attended by bookstore workers and owners, illustrators, and printers, but no writers, because it was a conference for workers, Seajay emphasized. "We were very influenced by Marxist ideas about laborers controlling their own labor. We didn't put the writers on a pedestal." The initial idea for Feminist Bookstore News came out of this conference as a way to stay in touch with each other. The first issue was published on October 14, 1976.

The week before the Women in Print conference, Seajay got notice that she could finally get into an electrician's class. During the conference Paula called to report that their loan from the credit union was approved. Elated, Seajay instantly decided to pursue the decidedly more risky venture of starting a feminist bookstore. So with $6,000 from the credit union, and a $2,000 loan from Paula's parents, they started Old Wives Tales.

Success in the Mission Dolores Neighborhood

The first store was at 532 Valencia St., below the Club for the Deaf. They were around the corner from the George Jackson Defense Fund, Rainbow Grocery, The Communist Party Bookstore, the Roxie movie theater, the Tenants Union, Artemis Cafe (a women-only cafe), Osento (a women-only bath house), Garbos (a lesbian-owned haircutting shop) and Amelia's (a women's dance bar--now called the Elbo Room). Angela Davis was a frequent customer at Old Wives Tales. Lesbians were proudly coming out in the Mission Dolores neighborhood and making it their own.

At the time Seajay lived in collective households, first, right around the corner on Rondell Avenue, and later on 21st Street between Valencia and Guerrero. "I would walk home at night and feel that it was the golden age of the world. It was a precious time, and I knew it might not last. I knew it was all so radical that I feared a repercussion. Look, if we were as threatening as we wanted to be, then we could expect some right wing vigilantism. Still, I expected that by the time I was 40 there would at least be socialized health care. I mean, at the time there was a War on Poverty. It was understood that it was poverty that made kids dumb."

They opened Old Wives Tales on Halloween, 1976, paying themselves $200 a month. Around this time Seajay and her housemates took on a foster daughter through a program for gay and lesbian teens who had run away to San Francisco. The first person they hired was a friend of Seajay's foster daughter, who worked part time and stayed for ten years. There was a great deal of internal pressure on participants as everyone tried to work in an egalitarian and cooperative way--not a familiar mode for anyone raised in a capitalist society. And this was in addition to the external pressure of trying to run a small business (bills, expenses etc.) After two years, in 1978, Seajay and Wallace broke up.

Wallace drove off and ended up in New Mexico, where she bought Full Circle books. Old Wives Tales became a collective instead of a partnership. They also moved from 532 to 1009 Valencia for more space. The time was a struggle, but the community really supported the store, and tourists and travelers came from all over to shop at and see Old Wives Tales. Most people easily felt comfortable upon entering, because the vision behind the project was a women-owned store where the whole community was welcome. Over the next few years, Seajay watched it grow into an integral and bustling corner of the women's community on Valencia Street.

Falling Apart

Around 1982, lots of internal hassles surfaced. Seajay had invited another lover to join the collective after Wallace left, and the break up that came a few years later was rather difficult--the collective also tried mediation. Then, like a lot of feminist organizations in the 1980s, there came discouraging problems around racism. The Old Wives Tales collective dealt with embezzlement, alcoholism, and went through more mediation as a group.

Exhausted with all she had put into Old Wives Tales over the years, Seajay was literally watching the store fall apart. By 1994 it needed to be fully rebuilt organizationally. Seajay decided to resign, but the collective wouldn't accept her resignation. "I was very burned out, but I stayed for a while because it does take skill to run a bookstore well." She advised the collective and passed on her formidable bookstore-running skills. Gradually the collective transitioned into an official non-profit and Seajay resigned. She didn't really recoup any part of her investment from Old Wives Tales when she left.

People without experience were running the store once Seajay left, and it was in and out of financial trouble. When A Different Light came to town from New York, it squeezed Old Wives Tales even more. They took business from Old Wives Tales mainly because Old Wives Tales began to look like old-fashioned feminism next to the slick New York-associated A Different Light. This was illustrated best by the two groups lining up on different sides of the S/M wars which were raging at the time. Some Old Wives Tales workers were critical of those who "acted out their childhood pain through sexual violence" while many Different Light people saw S/M as a liberating avenue to heightened sexual excitement and self-awareness.

In 1995, riddled with strife and debt, Old Wives Tales closed its doors. Seajay's attention was already turned full time to the Feminist Bookstore News and Network.

Although San Francisco is poorer for the loss of our women's bookstore, today there are 120 feminist bookstores all over the United States and Canada (150 loosely counted.) In April of 1997, Feminist Bookstore News will celebrate its twenty year anniversary of connecting women's bookstores across the country.

"We had a vision," Seajay said, "that women could learn to do for ourselves, that we could make our own mistakes, and I still believe this passionately."

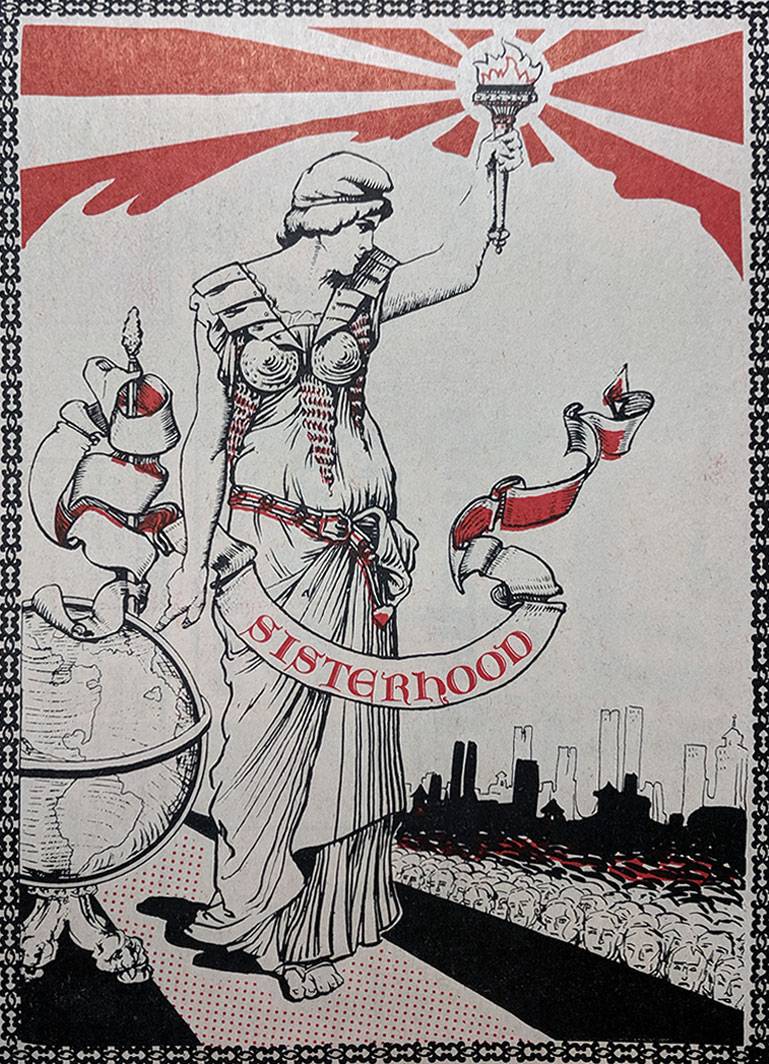

Centerfold from Leviathan newspaper, 1969.

courtesy Peter Wiley