Burnham Plan and Tenement Housing

Historical Essay

by John Baranski

This excerpt originally appeared in "Progressive Era Housing Reform," Chapter One of Housing the City by the Bay: Tenant Activism, Civil Rights, and Class Politics in San Francisco (see below for copyright and book information)

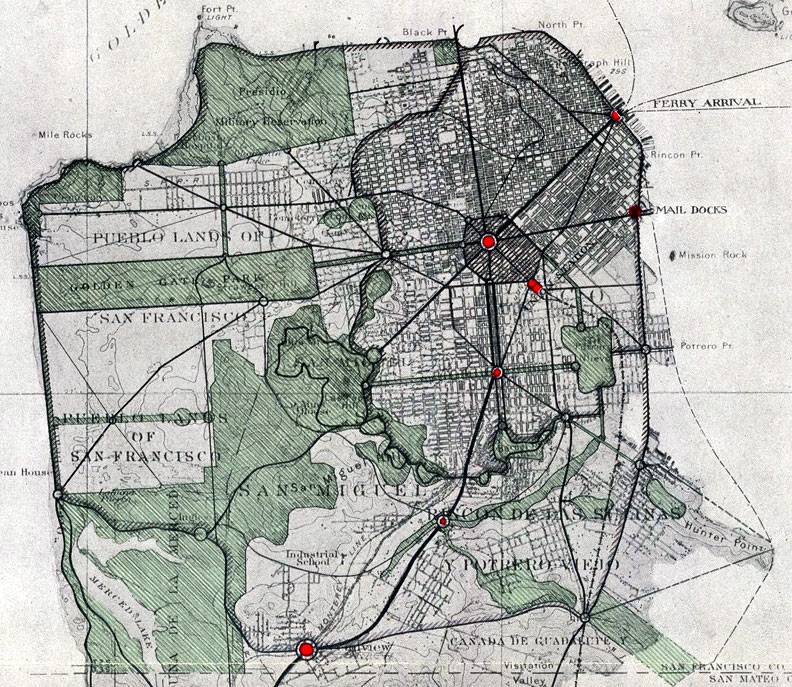

A version of the Burnham Plan's reorganization of urban arterials and street patterns.

The damage from the earthquake also revived interest in a major redevelopment plan. While Finance Committee and Finance Corporation members dispensed relief and built temporary homes, some of the city’s leaders worked a scheme called the Burnham plan, which, like Devine’s housing plans raised larger questions about the economic role of government. Two years before the quake, James Phelan, former San Francisco mayor and one of the city’s largest landowners, led a group of businessmen and politicians who hired Daniel Hudson Burnham to redesign the city. An architect and city planner, Burnham was a leading figure of the City Beautiful movement, whose participants viewed urban planning as a way to enhance a city’s physical design and foster social harmony. His plan for San Francisco drew inspiration from Europe’s imperial cities and called for wider boulevards, majestic public parks, a civic and culture center to serve the needs of residents and businesses, and planned residential developments. City leaders hoped the plan would help to maintain San Francisco’s edge and power over West Coast competitors, such as Los Angeles and Portland, and impose social order in a city marked by class conflict. The Burnham plan incorporated these hopes and reflected the latest ideas in international and large-scale urban planning.(10)

Prior to the 1906 fire, the implementation of the plan had languished because of its cost, its fifty-year time frame, and the need to put massive tracts of land under public control. The earthquake and fire renewed hope for the Burnham plan: Sup- porters saw in the rubble and ashes a chance to reinvigorate interest and debate. A public information campaign urged San Franciscans to approve the project, but the plan never found the necessary popular and political support. According to historians William Issel and Robert Cherny, “[n]either the strongest supporters of the plan nor its staunchest opponents would agree that city government ought to exercise the sweeping powers over private property necessary for the implementation of a comprehensive city plan.” Without the implementation of the Burnham plan or government housing programs, private developers and landlords controlled the shape of housing and urban development, and in the process they left substandard housing across the city.(11)

To reformers who believed dark, poorly ventilated, and shoddy housing generated social and civic problems, the post-quake housing conditions gave new urgency to housing reform. Alice Griffith wrote, “To one with eyes trained to seek for all that makes for the welfare of the people, the fire has left a print which will not be eradicated for years. The houses are rebuilt, but such has been the demand for homes, that both landlords and tenants have overlooked all but the barest needs of shelter.” Griffith worried about how these homes influenced an individual’s character. “The greatest want in this district, as in other parts of the city, is the social work. The existence of the camps, living in the shacks, drives the people—particularly the younger members of families—into all kinds of ill- advised amusements.”(12)

The city’s housing reformers followed their counterparts in other U.S. cities by focusing more on regulating the quality of housing than on pursuing large-scale housing projects. Despite the allure of public and cooperatively owned housing and limited-dividend housing,(13) these large-scale projects did not have much popular or government support in the United States. New York City housing reformer Lawrence Veiller, who wrote extensively on housing laws and was part of the international housing reform community, knew the benefits of large-scale housing projects and admitted that a focus on the physical nature of housing did “not touch the questions which most vitally concern the welfare of the great mass of people.” And yet, for the practical Veiller, the creation of government regulations and building codes to ensure safe housing was a good first step. As he put it, housing reformers needed to be “interested . . . in the quality of brick and mortar, in methods of fire-proofing, . . . in rivets and flanges of iron beams and columns.” He thought a gradualist approach to the housing question, through civic education and legislation, would slowly and continuously expand the role of government in housing and make housing better and safer.(14)

San Francisco and California housing reformers pursued his approach: In July 1907, the city of San Francisco passed the Tenement House Ordinance, which required builders to leave at least 30 percent of a lot open; and in January 1909, the state legislature passed the State Tenement House Act, which established standards to improve the health and safety of the state’s housing. Unfortunately, neither the city nor the state allocated adequate resources to enforce this early housing legislation, which meant that virtually no inspectors could be hired, leaving local residents and voluntary associations with the burden of enforcing the new laws. Nevertheless, in spirit if not in practice, the laws were the kind of legislative efforts promoted by housing reformers such as Veiller in the short term.(15)

To help build support for local and state housing legislation, San Francisco reformers used social science research methods to study California’s homes. These “social surveys” modeled those being conducted in rural and urban areas on both sides of the Atlantic and had the same purpose: to agitate those who were interested in problems of social welfare and get them involved in organizations working for social reform.(16)

previous article • continue reading

Notes

10. Kahn, Imperial San Francisco; William Issel and Robert W. Cherny, San Francisco, 1865–1932: Politics, Power, and Urban Development (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), 109–11; Michael Kazin, Barons of Labor: The San Francisco Building Trades and Union Power in the Progressive Era (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987); William H. Wilson, The City Beautiful Movement (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989); Gray Brechin, Imperial San Francisco: Urban Power, Earthly Ruin (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999); Rodgers, Atlantic Crossings, especially chapter 5; Robert Fishman, ed., The American Planning Tradition: Culture and Policy (Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2000).

11. Quote in Issel and Cherny, San Francisco, 110. Ocean Howell argues that a key source of opposition came from the Mission Promotion Association, which had become a political power in urban planning in and out of the Mission district. See his Making the Mission: Planning and Ethnicity in San Francisco (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015).

12. Quote in Telegraph Hill Neighborhood Association, Annual Report (1907).

13. For housing reformers, large-scale projects offered the most hope for addressing the housing problem and eradicating slum conditions, but these kinds of projects generally lacked government support and financing. Here are some definitions of various housing types, used in this discussion: (1) Limited-dividend housing offers investors a legal structure for a fixed return on their investment; the housing is affordable for tenants, of adequate quality, and allows the government a way to regulate the housing itself. (2) Public housing agencies build, own, and manage low-cost housing. (3) Cooperative housing creates a corporation that is run by occupant-owners, who act as a collective landlord under the guidelines of the corporation. See Rodgers, Atlantic Crossings.

14. Veiller’s idea of a gradualist legislative reform approach would focus on building codes (unexciting and technical but easiest to pass); the Tenement House Laws (better for dealing with light and ventilation and plumbing issues); and housing legislation (best for outlawing all substandard housing, whether owned or rented). Veiller, A Model Housing Law, especially preface and chapter 1, quotes on 11. For biographical information on Veiller, see Robert Bruce Fairbanks, “From Better Dwellings to Better Neighborhoods: The Rise and Fall of the First National Housing Movement,” in John F. Bauman, Roger Biles, and Kristin M. Szylvian, eds., From Tenements to the Taylor Homes: In Search of an Urban Housing Policy in Twentieth-Century America (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000).

15. San Francisco Housing Association, Annual Reports (1911, 1912, and 1913). See Veiller, A Model Housing Law.

16. San Francisco Housing Association, Annual Reports (1911, 1912, and 1913); Telegraph Hill Neighborhood Association, Annual Reports (1907 and 1911).

Excerpted from Housing the City by the Bay: Tenant Activism, Civil Rights, and Class Politics in San Francisco by John Baranski, published by Stanford University Press. Used by permission. © Copyright 2019 by John Baranski. All rights reserved.