Bohemian San Francisco Between the Wars

Historical Essay

by Kenneth Rexroth, written in November-December 1973, reposted from the collected columns of Rexroth at the Bureau of Public Secrets

Communist Party stages May Day demonstration on May 1, 1934, just a few short weeks before the epic waterfront strike began.

Photo: Bancroft Library

North Beach and Telegraph Hill — The Last Bohemia. Now that almost a generation has passed since the first Abstract Expressionists and Morris Graves lived here and the San Francisco Renaissance and the Beats started writing and the Tape Music Center began and San Francisco became for ten years the liveliest culture capital in the world and its artists and writers famous from Asunción to Reykjavik and from Irkutsk to Mexico City and the place every young intellectual wanted to go as soon as possible, it is hard to believe how provincial the City was between the First War and the Depression.

I hadn’t been here very long before I got a visit from the leading artist, who looked around the walls and said, “Waall I see you’re experimentin’ with abstract form like Matissey and Picassio.” Folks were nothing if not loyal to local talent. Everybody, but everybody, believed the greatest living poet was George Sterling, the greatest living novelist Kathleen Norris, and that Papa Hertz was an orchestral conductor and the rubbery sounds emitted by his Symphony were music. My wife and I had to admit it was a change of pace after Paris, New York and Chicago.

There were advantages, as there always are to provincialism and cultural lag. The marketplace was far away. It was quite impossible to make a living as an artist, writer or composer in San Francisco, so the practitioners of the arts were in it for love, and they were mostly very poor indeed. This economic situation produced a Bohemia very like that of New York or Chicago from the 1880s to the First War.

Montgomery Block, 1930s

Photo: Courtesy of Jimmie Shein

Another important factor was that Prohibition simply didn’t exist. There were several bars on Market Street alone where a perfect stranger could walk in and get a full whiskey glass of respectable moonshine or grappa for 25¢, and it was easy to find red wine for $2 a gallon or less. A studio in the Montgomery Block cost $12. Over on Washington and Sansome were even bigger rooms, gaslit, for $8-10 a month. If you had practically no money at all you could get free buttermilk at the Golden State Dairy nearby and in the produce district as the markets closed all the free vegetables you could carry away, and free fish at the wholesale fish market. There was another place where you could get free dried fruit. There was no problem, if you knew your way around, in maintaining a very healthful diet. None of the cheap hotels in North Beach cost more than a dollar a day. The cheapest Italian restaurants served a full dinner and a glass of red ink for 25¢, and you could put together a Chinese dinner at Yee Jun’s for 25¢ a person — or less.

The hangouts were: the Casa Begine, a wonderful restaurant then entering its decline — Mama and Papa Begine were growing old, and their customers were deserting Bohemia for the Establishment; the Telegraph Hill Tavern, run by a great cook and great lover and bad poet, a lady who called herself Myrtokleia, after a character in The Songs of Bilitis; and Izzy Gomez’s, at first on Pacific, across from the firehouse, immortalized in William Saroyan’s The Time of Your Life. The Casa Begine in its best days was a genuine artists’ and writers’ restaurant where people lingered long after splendid dinners in passionate discussions or intense chess games, and after many glasses of wine ended up singing until after midnight. It must have been something like the Closerie des Lilas in Paris in the 1900s, when the evenings were presided over by Paul Fort, the “Prince of Poets.”

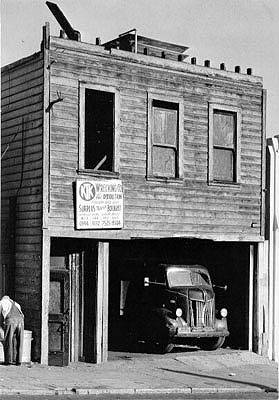

Izzy Gomez's old place on Pacific Ave., favorite haunt of many a San Franciscan in days not so long gone by.

Photos: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

Myrto’s was different. The customers were mostly pure Bohemians — people with artistic personalities but little or no artistic talent, who enjoyed many of the pleasures of the rich while sacrificing many of the necessities of even the poor. The atmosphere was one of muted orgy, liable to break loose at any late hour into gay, bedraggled abandon. Myrto and her friends were always getting busted at the annual arts ball for appearing in the altogether or as they say in French, à poil. Myrto’s was more like the Café Dôme in Montparnasse’s craziest days or the even crazier “bohemian tea rooms” of Greenwich Village or Chicago’s Near North Side — Grace’s Garret, the Purple Pup, the Green Mask, the Gray Cottage, all of them dead long before the Telegraph Hill Tavern was born.

Izzy Gomez’s was something else. Unique. Sui generis. It really was as portrayed in The Time of Your Life, except that it was also a favorite hangout for hardboiled, sophisticated newspapermen of the kind that flourished in the good old days when no self-respecting newspaperman, including even the editorial writers, believed a word of the Social Lie, but knew all the real answers. They gave the place a rowdy, slightly underworld character of half-suppressed brawl. Now they’re all dead. The last to go was handsome Pat O’Niall who died, fat and alcoholic, on the Pittsburgh Press, a legend of awe and wonder to his colleagues in what has come to be called “the profession of journalism.” Izzy’s grappa, the best liquor in town, was 25 cents a shot. He served nothing else but home brew. Bootleg big brewery beer was made only by the Organization and not allowed in San Francisco. For meals Izzy served thick, luscious steaks, French fries and salads — a considerable number of meals and liquor free, not just to starving artists, but to people he liked. I was always a little embarrassed to patronize the place because he would never take any money from me. If I brought guests for dinner I had to give them the money and have them pretend to be hosting me. Even so, Izzy would not usually take the money. [...]

San Francisco’s Bohemia, between the two world wars, may have been provincial, but in those days there was no question whatever that the laissez faire and dolce far niente of la vie méditerranée was stronger and lasted longer here than anywhere on that tideless inland sea itself.

San Tropez wasn’t in it with Telegraph Hill. Most of the hill was still unpaved. There weren’t even real streets on the north side and only rickety wooden staircases on the east. Two different old ladies herded goats in the vacant lots and kept them at night in barns that were part of their own homes. The Italians were almost all from North Italy, the largest contingent from Lucca. To this day the Lucchese have the largest town club in the Bay Area, and whenever I have visited Lucca all sorts of people greet me by name and invite me for a drink.

At harvest time the gutters were purple with overflowing refuse from the vine presses, and an atmosphere of wholesome orgy borne on the strains of mandolins, guitars and accordions enveloped the whole hill. This Latin virtú communicated itself most infectiously to the scattered bohemians who still constituted a very small minority. San Francisco must have been the only city in the United States where intellectuals drank wine rather than hard liquor or cocktails at their parties.

Even the sex was wholesome, though promiscuous. You seldom felt the frustration, tensions and combativeness so characteristic of Greenwich Village. Most parties or even just nightly get-togethers ended with singing. Six months going about on Telegraph Hill would have provided anyone with an immense repertoire of authentic folk songs, old English ballads and the highest quality of classic bawdy songs. Myrtokleia, and after her day the painter Richard Ayer, father of the young woman poet Hilary Ayer, had absolutely unlimited repertoires and could sing all night. So could a man I believe is still alive down in Big Sur, Harry Dick Ross, who had a bellow like the late movie actor Joe E. Brown — which covered the fact he couldn’t sing a note. All Telegraph Hill needed to be the Land of Cockayne come true were those roast pigeons flying around with a knife and fork sticking in them.

There wasn’t much other music in those days. King Oliver had played San Francisco in the early ’20s and so had “Frisco, the American Apache Dancer,” who was the first man to take a jazz band into Palace Time vaudeville.

But this spirit did not last. Perhaps the reason was that the black community in San Francisco was very small. It stretched from Ellis Street to Sutter and from Webster to Laguna, sparsely sprinkled amongst the predominantly Japanese population. Fillmore Street in those days was mostly Jewish. Still, one after another there were wonderful gathering places of the kind that came to be known as “after-hours joints.” The earliest I can remember was a speakeasy called, I think, Timmes’. It was a house, west of Fillmore a few doors, probably on O’Farrell, and it was like an ideal Harlem rent party that never stopped. Timmes’ served excellent liquor, red wine and very good grappo, which I believe he got from the same supplier as Izzy Gomez.

The place had a piano with a fine collection of ragtime rolls, but there was usually somebody around who could play it in an ultra-funky Jelly Roll Morton style. I don’t know where they came from since there was no market for their talents, but all sorts of musicians with all sorts of instruments would wander in and jam until dawn, while between the little tables the customers would roll and bump. After Timmes’ there was a succession of wonderful places. Elsie’s, Blackshears’, Jack Bryant’s in the tiny black district of seagoing folks at Pacific and Embarcadero. Timmes’ and Elsie’s had the friendliest atmosphere of any entertainment places I’ve ever been in. And Jack Bryant had the most beautiful waitresses I’ve ever seen, girls who’d make the chorus line at the Harlem Apollo Theatre look plain and dowdy.

There was, in those days, no hostility directed toward hip white people whatever. Although there were very few of them at the tables, there were always plenty of white musicians jamming, and welcome.

By the time Blackshears’ came along, a faint note of hostility had begun to appear and by the time of Jimbo’s, the most famous of them all, black hostility toward whites gradually became oppressive. When Wilma opened Soulsville a few years ago, white musicians were quietly frozen off the stand — to her distress. I must say that I never felt any discrimination or hostility whatsoever either in the after-hours joints or in regular clubs like Jack’s or the Club Alabam. The latter was pretty funky but Jack’s was very high-class, and although the black community was small, functioned as a kind of black Hungry i. Jack’s introduced a remarkable list of entertainers, even the great bass singer Kenneth Spencer, who went on from Sutter and Fillmore to fame in Bach, Mozart and Monteverdi in Europe.

Years later I came into a Chinese restaurant near the Sorbonne in Paris. Behind me a powerful bass voice was speaking and my wine glass trembled in front of me. “My God!” I said to my wife, “Kenneth Spencer’s in this room somewhere!” So he was. He was with Alberta Hunter, an old friend of mine from Chicago, the first woman to ever sing blues on the concert stage (though the surviving records don’t sound very bluesy). We spent the night talking about the old days.

They were pretty good old days. There was probably less interracial tension and less prejudice against blacks in San Francisco than anywhere else in the world. Private parties, clubs, after-hours joints and big dances were places of pure joy. Something that I have always thought very significant of interracial naturalness, not just tolerance, is the incidence of white male-black female interracial couples. In those days in a place like Jack’s or Timmes’ there were almost as many as the other way around. Alas, today interracial tensions have grown so severe that natural contacts have almost died out — first in interracial organizations like CORE and at last, and finally, in jazz.