Bohannon’s Challenge to BART

Historical Essay

by Julia Paris, 2021

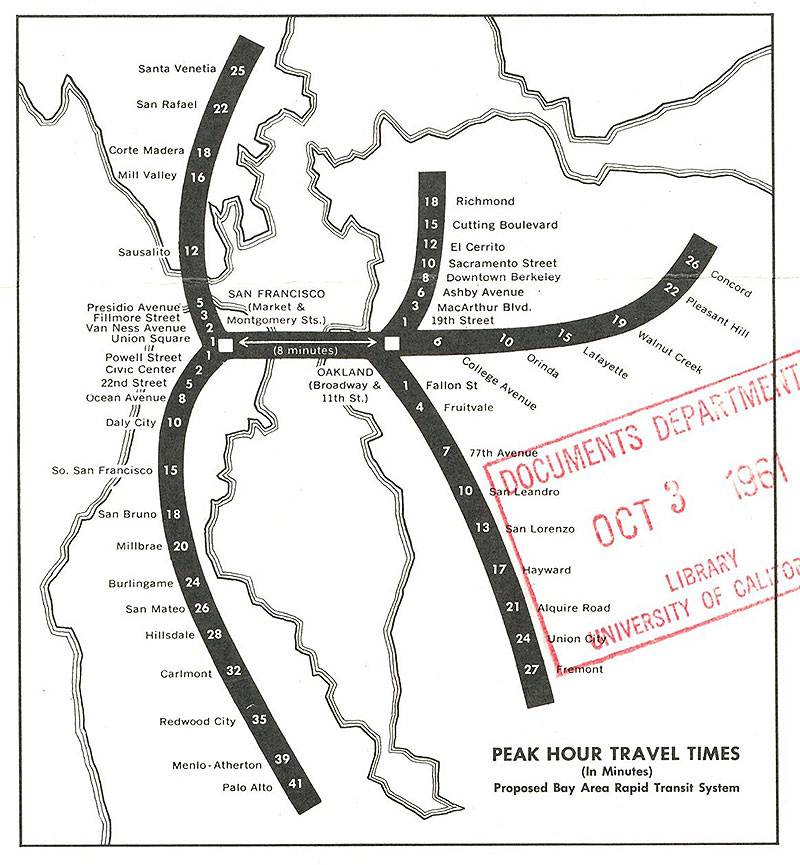

| The original plans for BART included a “Peninsula Line” traversing San Mateo county; however, the construction of this line was cancelled when the county’s Board of Supervisors voted to withdraw from the BART district in late 1961. This decision is commonly attributed to the high cost that BART would have imposed on the county; however, real estate developer David Bohannon was also a driving force behind the decision to withdraw. Bohannon likely opposed the proposed BART line in order to protect the profitability of his commercial developments, particularly the Hillsdale Shopping Center. There is also strong, though circumstantial, evidence that Bohannon’s opposition to BART was founded in a desire to maintain San Mateo’s racial exclusivity. |

August 1961: BART plans (peak hour travel times).

Image courtesy of Eric Fischer

David Bohannon may not be a household name in the Bay Area; however, he played a pivotal role in shaping the region as we know it today. Bohannon was among the most prominent developers of both residential and commercial land, including San Mateo’s Hillsdale Shopping Center, in the Bay Area (1). He was also an “avowed transit foe”(2) who “worked assiduously”(3) to defeat the proposed inclusion of San Mateo county in the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) system. Though Bohannon’s role in the San Mateo’s decision to leave BART is rarely acknowledged, his influence was highly consequential. This article explores the avenues through which Bohannon advocated against San Mateo’s inclusion in the transit system, as well as the economic—and perhaps racialized—motives behind his fierce opposition to BART.

When the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District was initially formed in 1957 to design and implement the BART system, it comprised five counties: Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, San Francisco, and San Mateo (4). The original plans for BART projected that, in the first phase of construction, these five counties would be connected by a futuristic train system, with Santa Venetia, Richmond, Concord, and Fremont each acting as the terminus for different train lines (5). Though Santa Clara county was not officially a member of the transit district, one BART line was also planned to end in Palo Alto after traversing San Mateo county.

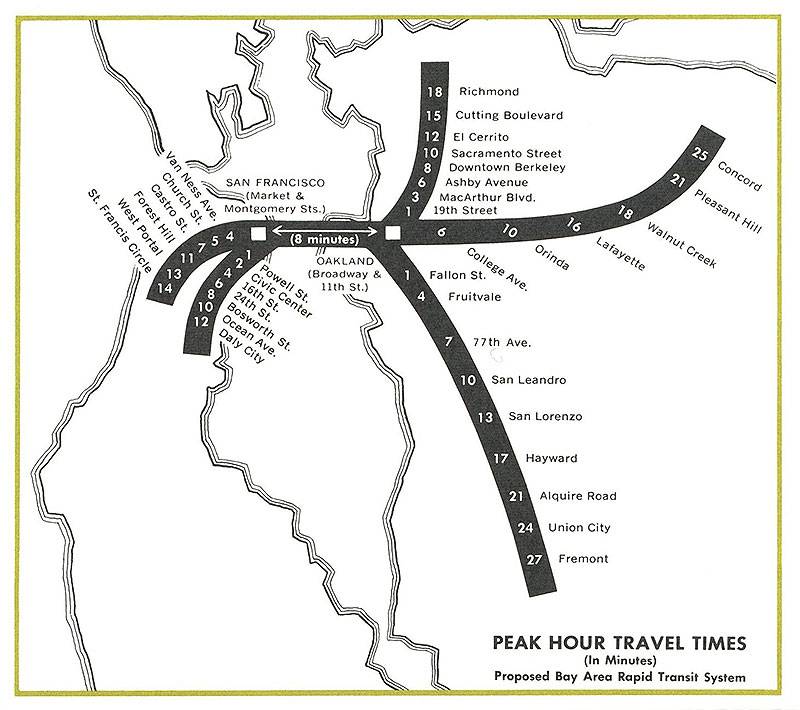

In order to begin construction on BART, bonds needed to be approved by a plebiscite in the member counties (6). The measure was added to the ballot for the midterm election on November 2, 1962, and required 60% approval averaged across all five member counties in order to be enacted (7). However, before the original BART plans could be voted upon by the general public, a major change occurred: in early December 1961, the San Mateo County Board of Supervisors announced that they would be withdrawing from the transit district (8). Soon after, in early 1962, Marin followed suit; by some accounts, they were pressured to leave the transit district because officials were concerned that, without San Mateo’s tax base, the expense of the Marin line would be prohibitive (9). (Other accounts dispute this notion, noting that serious discussions of Marin county’s exit from the transit district, particularly with regard to the feasibility of running trains on the lower deck of the Golden Gate bridge, had already begun before San Mateo announced its departure (10).) Regardless of whether Marin’s exit from the transit district can be directly traced back to San Mateo’s departure, the decision of the latter to abandon BART fundamentally changed the future of transit in the Peninsula.

April 1962: BART plans (peak hour travel times).

Image courtesy of Eric Fischer

At the time, accounts of the San Mateo County Supervisors’ decision to depart from BART highlighted the high cost of the transit system, coupled with the perceived duplication of existing Southern Pacific (now Caltrain) rail service down the Peninsula (11). To this day, many popular accounts (including BART’s official history page) point to the cost and redundancy of the proposed system to explain why the planned BART construction in San Mateo never occurred (12). For example, a 2019 SFGATE article explains that “the county already had commuter trains operating on the old Southern Pacific right-of-way and balked at taking on the hefty cost of a new rail system” (13). While there is truth to these accounts, they obscure a key influence that played a pivotal role in the decision to leave the district: the advocacy of San Mateo commercial interests and, most notably, real estate developer David Bohannon (14).

In the years before the general election, and particularly in the final portion of 1961, Bohannon staged a multifaceted campaign against the proposed BART routing. He presented a barrage of arguments against the proposed transit connection, including that the price to taxpayers was too high; that most movement occurred from east to west in the county and that BART would duplicate the Southern Pacific (Caltrain) service without improving mobility across this “horizontal” dimension; and that the increased taxes would discourage business investment in San Mateo and favor the neighboring Santa Clara county (15). Bohannon attended political meetings, including a meeting of all 16 San Mateo county mayors, in order to pressure the county’s policymakers to remove San Mateo from the transit district (16). Bohannon also appealed to the general public, speaking at a number of events hosted by organizations such as the Town Hall Association (17) and the American Association of University Women (18), in order to present his arguments against BART and occasionally to formally debate BART officials.

In addition to presenting his own personal views on the topic, Bohannon enlisted powerful business groups to support his anti-BART agenda. For example, the president of the San Mateo County Development Organization – which Bohannon had founded – argued that the project “would boost the county tax rate and thus shunt new industries into Santa Clara county” (19). Bohannon went so far as to commission a study of the transit proposal by the Governmental Research Council, a “taxpayer-protecting” (20) organization composed of developers and builders, of which Bohannon was president (21,22). Though Bohannon insisted that the study was completed independently from his own stance on the BART question, the Research Council’s recommendations, published in September 1961, aligned very closely with the arguments that had been promulgated by Bohannon at county events for the preceding months (23).

Bohannon’s pressure campaign was highly effective. In December 1961, months before the decision was originally anticipated, the San Mateo county Board of Supervisors voted to leave the BART District. While a number of other lobbyists had also played important roles, including a former Southern Pacific executive who sat on the Board of Supervisors (24), it was Bohannon who was singled out by his contemporaries as the individual who had spearheaded the anti-BART campaign (25). After San Mateo’s withdrawal from the BART District was publicly announced, BART Director Adrien Falk stated to the San Francisco Chronicle that “a small group of big business interests [had] created such an atmosphere of negativism that I doubt whether we would have been successful in putting a resolution through the Board of Supervisors opposing sin” (26). Falk’s statement was specifically linked to Bohannon (but no other business lobbyist) by the Chronicle (27).

Though Bohannon claimed to oppose BART out of concern for all San Mateans’ personal and business interests, he personally had a clear stake in the issue. As a developer of malls, including the Hillsdale shopping center in San Mateo, his economic success partially relied upon local buying power being funneled into his shopping centers. Bohannon appears to have used his significant influence with partners in government to make sure this pattern would be maintained. For example, in 1959 Bohannon was the master of ceremonies for an event in which the San Mateo city planner presented a vision for the city’s future that included “intensive apartment development for San Mateo, boosting the purchasing power at the downtown district and the Hillsdale shopping center” (28). BART could have presented a threat to this vision. By some accounts, Bohannon was concerned that easier access to San Francisco’s stores (facilitated by BART) would lead many San Mateans to do their shopping in the city instead of visiting his establishments, causing him to “fear that he [would] suffer an economic deflation” (29, 30).

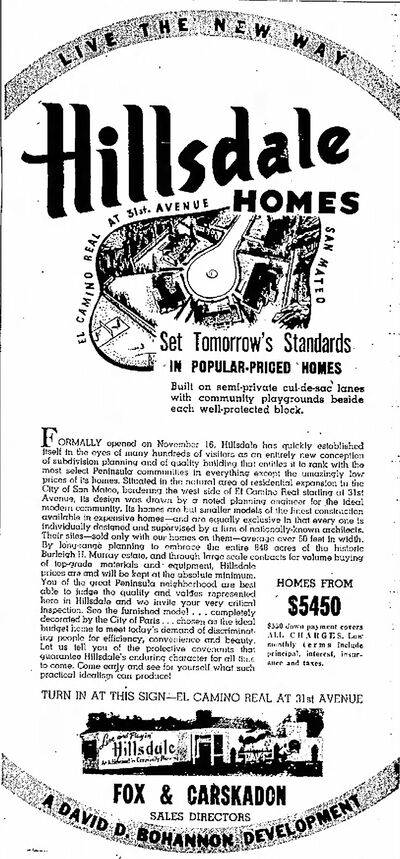

Concerns about shopping patterns may not have been Bohannon’s only personal reason to oppose BART. In addition to building shopping malls, Bohannon was a major player in the Bay Area’s residential developments – and he was among the Bay’s biggest developers of whites-only housing (31). This racial segregation, including through restrictive covenants that prevented the sale of homes to Black people (32), was marketed as an attractive feature of Bohannon’s developments. For example, Bohannon’s residential development adjacent to the Hillsdale mall had been advertised in newspapers with the following note: “Let us tell you of the protective covenants that guarantee Hillsdale’s enduring character for all time to come” (33).

Bohannon’s fingerprints were already on some of San Mateo’s racialized plans and housing policies. At the aforementioned 1959 presentation by the San Mateo city planner, during which Bohannon was the master of ceremonies, the discussion of purchasing power at the Hillsdale shopping center was followed by a focus on “blight” (34). The city planner showed aerial photos of San Mateo (taken from a flight piloted by David Bohannon Jr.) in order to emphasize that the city had “no blighted areas” (35). Though “blight” is, on its face, a race-blind term, areas considered “blighted” were often those with poverty and/or a non-white population (36).

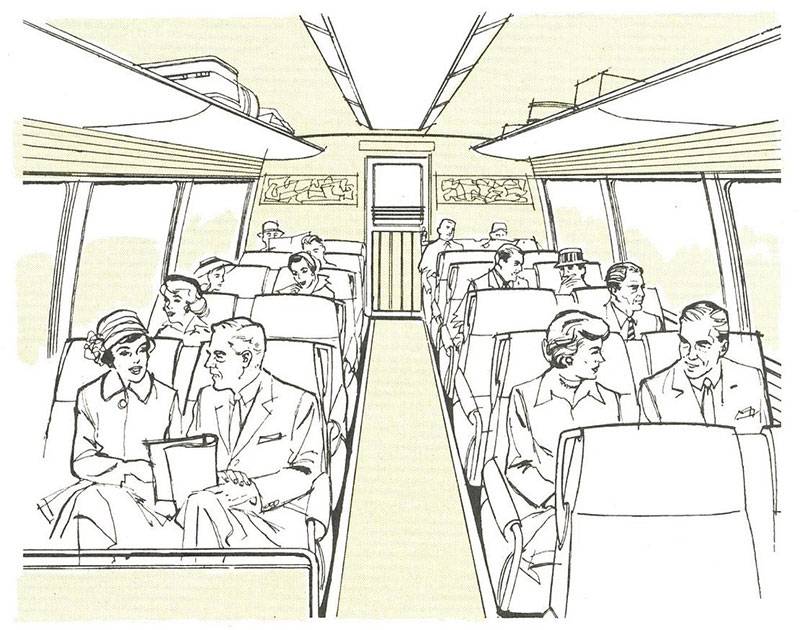

September 1960: BART marketing materials, depicting a racially homogeneous clientele.

Images courtesy of Eric Fischer

Because he developed whites-only housing, Bohannon clearly had an interest in ensuring that San Mateo remained – and was perceived to be – a white county. By making San Mateo more accessible to people without cars, particularly people from the core of San Francisco, Bohannon may have worried that BART would increase the number of non-white people in San Mateo.

In this context, Bohannon’s advocacy against BART could be viewed as an attempt to limit the movement of non-white people into San Mateo and therefore maintain the region’s racial exclusivity. This would not have been the first time that Bohannon executed a pressure campaign on local politicians to protect the racial exclusivity of his developments; just five years earlier, when a developer attempted to build an integrated housing project next to his whites-only Sunnyhills development in Milpitas, he pressured the Milpitas City Council to raise the fee for sewage in the development, delaying the construction of the integrated housing for years (37). Bohannon was also a member of the 1964 “Committee for Yes on Proposition 14” (38) which successfully campaigned to pass a proposition nullifying California’s Fair Housing Act and allowing racial discrimination in housing transactions (39). (Proposition 14 was declared unconstitutional in 1966 (40).)

Between the maintenance of his racially exclusive housing communities and the concentration of San Mateo buying power at his own shopping centers, David Bohannon appears to have had two clear reasons to oppose the extension of BART into San Mateo. It is impossible to determine the relative importance of these two reasons; what is clear is that Bohannon was extremely effective in achieving his aim. One can only imagine how the Peninsula would have developed if Bohannon had not gotten his way.

December 1940: Advertisement of Bohannon properties, highlighting their racially restrictive covenants.

Image via Newspapers.com

August 1960: Newspaper advertisement for Bohannon Properties in Santa Clara.

Image via Newspapers.com

November 1977: Advertisement for homes in Sacramento’s “Bohannon country.”

Image via Newspapers.com

Notes

(1) Rothstein, Richard. 2018. The Color of Law: A forgotten history of how our government segregated America. New York, NY: Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, p.125.

(2) San Francisco Chronicle. 1961. “San Mateo Hearings: Transit Official Raps Proposal As It Stands.” December 8, 1961.

(3) San Francisco Chronicle. 1962. “Falk Blasts Foes of Transit Plan.” January 27, 1962.

(4) Bay Area Rapid Transit. n.d. “A History of BART: The Concept is Born.” Bart.gov.

(5) Healy, Michael C. 2016. BART: The dramatic history of the Bay Area Rapid Transit system. Berkeley, CA: Heyday, p.42.

(6) Healy 2016, p.38.

(7) Healy 2016, p.2.

(8) Healy 2016, p.2.

(9) Dyble, Amy L. 2003. “Paying the Toll: A Political History of the Golden Gate Bridge and Highway District, 1923-1971.” PhD Dissertation, 2003, (pdf) p. 327.

(10) Dyble 2003, p.328.

(11) Zwirling, Stephen. 1974. Mass transit and the politics of technology; a study of BART and the San Francisco Bay area. New York, NY: Praeger, p.35.

(12) Bay Area Rapid Transit. n.d. “A History of BART: The Concept is Born.” Bart.gov.

(13) Moffitt, Mike. 2019. “Marin County could have had BART, but backroom politics got in the way.” SFGATE, September 3, 2019.

(14) Healy 2016, p.49.

(15) Golding, George. 1961. “Bohannon Opposed To Rapid Transit.” San Mateo Times, August 26, 1961.

(16) Golding 1961.

(17) San Mateo Times. 1961. “Rapid Transit Debate at Mills High.” November 2, 1961.

(18) San Mateo Times. 1961. “Rapid Transit Debate Here.” November 11, 1961.

(19) San Francisco Chronicle. 1961. “San Mateo Hearings: Transit Official Raps Proposal As It Stands.” December 8, 1961.

(20) Chrisholm, Donald J., Jonathan B. Bendor, Martin Landau, Melvin M. Webber, Philip A. Viton, and Seymour Adler. 1980. “Redundancy in Public Transit: The political economy of transit in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1945-1963.” U.S. Department of Transportation, Urban Mass Transportation Administration.

(21) San Francisco Chronicle. 1961. “District Criticized: Peninsula Report On Transit Plan.” September 27, 1961.

(22) San Mateo Post. 1961. “Fail to See Advantage to Mateans.” September 27, 1961.

(23) Ibid.

(24) Grefe, Richard, and Richard Smart. 1975. “History of the key decisions in the development of Bay Area rapid transit.” August McDonald & Smart, Inc., 1975, p.38.

(25) Chisholm et al. 1980.

(26) San Francisco Chronicle. 1962. “Falk Blasts Foes of Transit Plan.” January 27, 1962.

(27) San Francisco Chronicle. 1962. “Falk Blasts Foes of Transit Plan.” January 27, 1962.

(28) San Mateo Times. 1959. “Master Plan Gives Outline of Future.” June 3, 1959.

(29) San Mateo Times. 1961. “San Matean's 9-Point Plan Repudiated.” December 7, 1961.

(30) Grefe and Smart 1975, p.37.

(31) Rothstein, Richard. 2020. “The Black Lives Next Door.” New York Times, August 14, 2020.

(32) Rothstein 2020.

(33) Rothstein 2020.

(34) San Mateo Times. 1959. “Master Plan Gives Outline of Future.” June 3, 1959.

(35) San Mateo Times. 1959. “Master Plan Gives Outline of Future.” June 3, 1959.

(36) Mock, Brentin. 2017. “The Meaning of Blight.” Bloomberg CityLab, February 16, 2017.

(37) Rothstein 2018, p.129.

(38) San Francisco Examiner. 1964. “Prop. 14 Drive Intensified.” September 29, 1964. .

(39) Dougherty, Conor. 2019. “Overlooked No More: William Byron Rumford, a Civil Rights Champion in California.” New York Times, August 7, 2019.

(40) Dougherty 2019.