Bishop James Pike

Historical Essay

by Art Peterson

Bishop James Pike during construction of Grace Cathedral in 1962.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Visitors to San Francisco’s majestic Grace Cathedral hoping to pick up something of the vibe emitted by the eccentric and charismatic former Bishop of California James Pike will need to look past the Gilberta doors, the radiant rose window, and the Old Testament stories rendered in luminescent stained glass. Rather the special qualities of the man, who in the 1960s made the cathedral his center of operation, are more clearly embedded in his commission of two other stained glass works on display: one of astronaut John Glenn the other of Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, admittedly outstanding men, but probably nobody’s Christian icons In the 1960sSan Francisco, Pike was a perfect fit for San Francisco, a man always ahead of the curve. He preached against racism, apartheid, capital punishment, anti-Semitism and farm worker exploitation. He supported gay rights and pushed for a “fair wage” for San Franciscans.

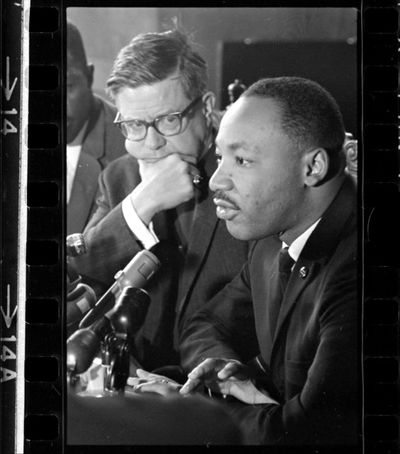

Bishop James Pike enjoys a laugh with Reverend George L. Bedford and Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. at Grace Cathedral, May 29, 1964.

Photo: San Francisco Examiner via Bancroft Library, BANC PIC 2006.029 138917.01.03--NEG

He invited Martin Luther King to speak at the Cathedral right after King’s Selma March. And as the VietNam war heated up, he traded in his bishop’s pectoral cross for peace symbol neck wear. Given the times, all of this might have passed muster with the church hierarchy. It was, however, his views on church doctrine that made the elders squirm. As Bishop of California he dismissed much of what the church held near and dear. For starters, he challenged the virgin birth and the concept of hell. Joan Didion comments on how he “streamlined” the Trinity by omitting the son and the Holy Ghost. To Pike none of this was heresy. He was merely “sweeping away the unnecessary.” “Fewer beliefs are more belief,” he said.

Unsurprisingly, his superiors found these rebellious interpretations hard to swallow. Three times in the 1960s the bishops geared up to try him for heresy. Each time they pulled back, perhaps on the advice of their PR department, nervous about stirring up muddy doctrinal waters. But, finally, in 1968, tiring of the ongoing tug of war, Pike abdicated, a resignation that was accepted with alacrity by his superiors. A year later he left the church entirely, labeling it a “sick and dying institution.”

There were hints from the beginning that Pike was not going to lead a humdrum life. Twice his doting mother enrolled him in the Better Baby contest at the Oklahoma State Fair. Twice he won. In later years he told stories of how as little more than a toddler he had read the phone book cover to cover and how he had devoured the Encyclopedia Britannica by age 10.

Drawn to a spiritual calling,he set out for New York City where he attended the Union Theological Seminary, studying with such religious heavyweights as Reinhold Nieber and Paula Tillich. It soon became clear that Pike would be no garden variety preacher. At a young age he was elevated to a plum assignment as Dean of New York City’s St. John of the Divine Cathedral where he preached to close to 4000 parishioners each week. An inveterate self-promoter, Pike knew the value of a well-timed press release. When he turned down an honorary degree from the University of Tennessee because of the university’s policy of not admitting African Americans he made sure the New York Times knew about it.

But his greatest attention grabbing coup during these years was the Dean Pike Show, a TV program in which he engaged in innocuous banter, slipping in his support for issues like birth control and racial equality. He finished each broadcast with a five minute spiritual pep talk he called “a commercial for God” The show soon eclipsed the competition, Bishop Fulton Sheen’s “Life is Worth Living” program. Pike appeared on the cover of Time. He was, the publication, said the “new public face of Christianity.”

But arriving in San Francisco, Pike had more of a rough go, and not just because of his tug of war with the guardians of the church’s bedrock convictions. The man’s personal habits struck many as little off-putting for a man of the cloth. A divorced man, he managed finagle an annulment in order to clear his way for his California appointment. He was a chain smoker, a user of drugs and an alcoholic until he was more or less rescued by Alcoholics Anonymous. His womanizing was legendary He was said to have a hot line installed in his office, available to take calls from whatever current mistress needed to contact him. Careless in his personal life he shed women as casually as he habitually let the cardboard backing of fresh shirts fall to the floor and remain there. Toward critics of this behavior he turned petulant, considering them petty and judgmental.

However in the mid-sixties life began to close in on him. His son committed suicide and his daughter attempted suicide. His mistress died of an overdose of sleeping pills in his apartment. His response was to carry her down the hall to her rooms, destroy evidence, lie to the police, and then perform the eulogy at her memorial.

Obsessed with his son’s death, Pike became a target for spiritualists and mediums, attending séances where he claimed he was able to contact the young man.

Pike’s last chapter seems an apt bookend for his novelistic life. Having given up on the church but not on Jesus, he set out with his third and much younger wife, Diane, to retrace the steps of Christ’s journey in the wilderness of the Quinan Desert. Armed with only an Avis map and two bottles of coke, the couple soon became disoriented. Separating, Diane went in search of help. Returning, Pike was nowhere to be found. Search crews looked for him for days,finally discovering his body where had fallen of a ledge to his death.

As it happened the Episcopal House of Bishops was meeting during the search for Pike. The clergymen were asked to pray for him. There was some hesitation but the group finally granted him a prayer—along with one asking the Lord shine his light on Ho Chi Minh, communist leader of North Vietnam.

There is no evidence that Pike would have been offended by this damming with faint praise In one of his last public statements he said, "The poor may inherit the earth, but it would appear that the rich — or at least the rigid, respectable and safe — will inherit the church."

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. at Grace Cathedral with Bishop James Pike, May 29, 1964.

Photo: San Francisco Examiner via Bancroft Library, BANC PIC 2006.029 138917.01.13--NEG