Attack on a Military Police Installation, July 1970

Primary Source

This article was originally published under the title "A Bomber’s Tactical Description of the Attack on a Military Police Installation" in Scanlan's, Vol. 1, No. 8, January 1971, the "Suppressed Issue: Guerrilla War in the USA" which had to be printed in Canada to overcome the refusal of U.S.-based printers to do it.

On July 28, 1970, the Armed Forces Police headquarters in San Francisco was bombed by three civilians, two men and a woman. The following is an interview with one of them.

Why have you decided to give us this description of the bombing of the military police station in the North Beach area?

We realized we were making a mistake. Our actions were not being clearly defined. We weren't able to provide people with an understanding of what we are trying to do . . . we weren't explaining the importance of violence in bringing the war to America. . .we hadn't explained to people why we picked this obscure station and did what we did.

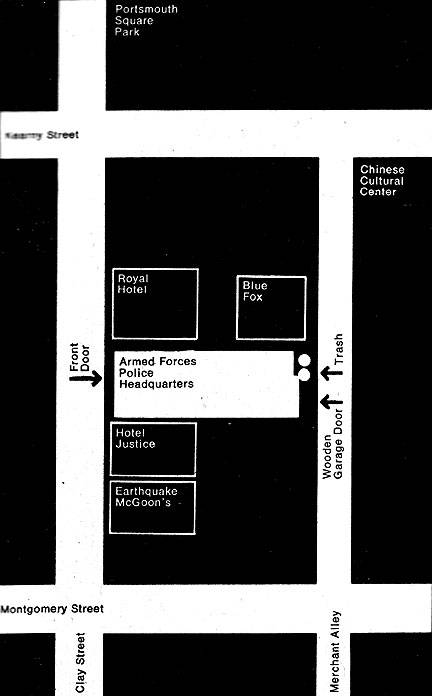

Map of target at edge of North Beach, San Francisco.

Image: Scanlan's

Could you give us the chronology of events that led up to your action?

Well, we had come together as a group to begin to engage in various acts of violence. We decided that we would participate in the new kind of struggle—that of armed struggle—but not necessarily withdraw from other political activity. We planned to develop a new life-style for dealing with problems.

Of course we had discussions about what target we would attack. The corporations and the pigs and the various targets that now occupy the consciousness of: all young American radicals ran through our minds. We thought about the new Bank of America Building, but that's too big and sloppy and wouldn't be very effective. And we thought about the new police station—but the increasing security in police stations would make it difficult to strike. Our actions are always designed to maximize significance and minimize getting caught. Because right now we realize that we can't destroy the police mechanism or the corporate mechanism. We realize we're at a very elementary stage—the stage of the theatrical.

Once you realize the absolute historical necessity of armed struggle, you can't organize a demonstration anymore. You might be able to attend one, but you can't invest your political efforts in trying to make peaceful-political changes. All the people in our group had realized that and that was the basic unity of the group. We didn't have any major unity or strategy or tactics. We weren't prepared at that time to engage in direct personal violence unless absolutely necessary in terms of self-defense. We felt it would be possibly alienating to engage in the same kind of personal violence that the governing structure gave us every day. We thought we would try and begin in another range and experiment in another possibility of physical property damage because we felt that was paramount in the consciousness of America.

Let's go from here to this action that happened.

Well, we found that the most important institution in America is the military. It's the military that the Vietnamese people face every day. They don't face Bank of America directly, they don't face our universities directly, they don't face the city government or the tactical pigs. The thing they really face is the U.S. military, the foot soldiers. Now, basically we were saying that we were -declaring war in unity with the Vietnamese against the military operations.

We realized, of course, that the military itself was also stratified just like American society, that there were all classes, all kinds of people in the military—people that had been forced into it by the very nature of American capitalism. They were slaves to the military. So, with that realization and with the realization that these men were trained military experts who could also become involved with the struggle against imperialism and racism, we felt that we would have to be very discriminating in our attacks on the military.

Now, until the time when we did our action, we followed other actions. That's one of the main things you get into as a group. You wait every morning to read the newspaper, you listen every day to the news. You're always getting in touch with the other members and discussing what actions have been created, so you are abreast of what's going on. And that becomes your life—armed struggle is your life.

We thought about who the greatest oppressors of the GI's were and we knew the main oppressor was the commander or the lifer. The actual mechanical apparatus of the lifer is oppression of the foot soldier—the average guy. We were aware that before every GI in the country goes to Vietnam, he comes to North Beach. Then, of course, there are the GI pigs—the people who pick up the deserters, the resisters, the trouble-makers. Weed seen several occasions in which GI's had been busted. So, we realized that to these guys, the real instrument of oppression was that military policeman. And we went on to investigate that. In other words, because of the role of the military policeman in the North Beach vicinity, we began to understand that it was necessary to attack that symbol.

What particular target did you pick?

The military police station, the Armed Forces Police Station, which is in San Francisco. It's located on Clay Street. It's rather obscured, even most of the people in the area don't know about it. This was one of the key reasons it was picked as a target-to emphasize its very presence, the fact that such a police station could exist and no one even know about it. The police station itself was in a civilian community (which was an interesting contradiction in that they were military police and they didn't get on very well with the civilians in the area), so we didn't feel that we would be alienating any of the people in the area. They'd wake up in the morning and it would be: "Oh well, the military station has been bombed." The main reason it wouldn't be important in their lives is because in no way does that military station serve anyone's interest in the area. It doesn't protect, it doesn't defend, it doesn't procure—all it does is oppress.

Hotel Justice on Clay Street in 1964, small white building at left of image is the building that was bombed in 1970.

Photo: J. Alan Canterbury, courtesy San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

After the picking of the target what was done? Was there reconnaissance planning, were there charts made?

We planned in depth. A number of us sat around and we discussed what would be the way, militarily, to execute this action. We decided to do something with that station. So we went and used some of the simple tools of reconnaissance.

We worked with a real map, a very detailed map of the area, because there are other police stations in the area—we knew where they were and watched their patrols and had a basic understanding about how the area was kept under surveillance by the local pigs. The civilian pigs and military pigs are very close.

We decided this was a fairly easy action. There were one-way streets going both ways-main streets. Late in the evening there's very little chance of congestion and usually the pigs don't patrol that area because it's downtown and very visible and light.

Previous to the incident, we began to live a social existence in that area. We'd go there for our meals—we'd eat, in Chinatown or North Beach. We'd walk around that area. We'd get entertained there. We'd get high there. When we had free time, we'd spend it there in bookstores. The key thing always is to understand the area—to know where to go. We began to live there and to feel settled about the issue and then we picked a time when we were going to strike-and then the main thing of course was to plant the bomb. See, we knew it was absolutely simple .to plant any device.

We certainly didn't want to harm any civilians. Definite precautions were taken not to. We took great precautions not to interrupt any civilian activity in the area or any GI activity. See, we consider the GI, the non-com, the foot soldier, to be a civilian. Whereas we consider the lifers and the military structure and the police structure of the military to be a more permanent structure—a structure which is evolving to a more Gestapo-type existence. Of course we wanted to isolate our acts of terror from any other elements of the population.

So the two main problems were planting and escape. That area happens to be particularly good for escape because it's filled with traffic. Because it's constantly congested and there are people around, you are never out of place. So we felt that escape was not much of a problem. Part of our discussion was about how to develop an untraceable escape. And that was also fairly easy.

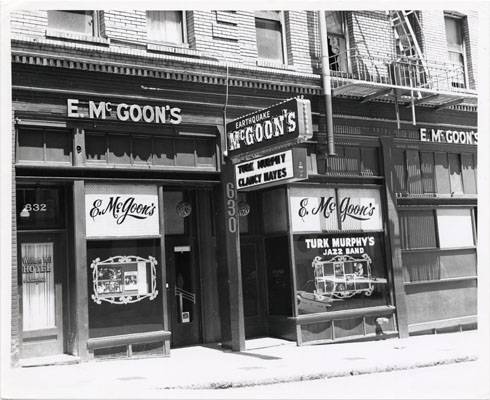

Earthquake McGoons, just two doors down from the well-hidden Military Police Station.

Photo: J. Alan Canterbury, courtesy San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

How did you go about doing the actual action?

First we prepared the weapon. There was substantial discussion about what kind of weapon to use. Should we shotgun the place or whatever? What kind of attack? We finally decided on a fairly simple kind of pipe-bomb. The ingredients that were used in this pipe-bomb are not super easy to procure but it's fairly easy to create. The device we used was approximately. . . Okay, let me tell you this. . . all the things that we used were totally untraceable in that they all were stolen. Stolen from someone's home, stolen from a store, a hardware store. . . we stole some pipe from a construction sight. The whole point of the pipe-bomb is that it is a people's weapon. Just about anyone can make one of these. So we stole what we needed and then we made up a dynamite-type base which would be fairly effective. My own particular task was to detonate the device, and to arrange a timing mechanism for it, since I had volunteered to plant it.

Let's talk about the actual planting of the device. How was that carried out?

There's an alley that runs behind the pig station. The back door of the station—which faces on the alley—is made of wood. This is the weakest spot in the whole building and the point we chose to attack.

Anyway, this alley was lined with trash cans. The military police station put their trash out there, too. So we figured there would be no better place than a trash can to put the bomb. Our main concern was that the device be in a place where there would be no question as to what our target was. Secondly, the trash can would provide a good cover for our device. There were times when the wooden door was open, but we thought it would be difficult to get inside.

There had never been attacks on this station before. That's one of the reasons we picked it. It had remained obscured in that commercial community. That evening we went by there several times. First we had dinner in the area earlier in the evening. Then we walked around and got a feeling that was fairly comfortable.

Early in the day we hid the device in a park. This park was a key staging area because it allows perfect vision down both the alley and Clay. In the evening we came back, had dinner and went to the park. Then we walked around North Beach and the topless area just like any tourist does. We walked around very casually—we were dressed very conservatively. We looked just like anyone else on the street.

What did you do to execute this action?

Let me just describe very simply what was done. There were basically three people. One was a woman. She was stationed in the park and her job was to monitor this area. She and I were in visual contact always. We had created various signals to communicate with one another. The first thing I did was proceed down the alleyway and at the time there was a building under construction across the way from the back of the station. . .

Were you driving or parked?

We were already parked. We parked two vehicles a block away on a one-way street which was part of the get-away plan . . . we would be leaving by two one-way streets.

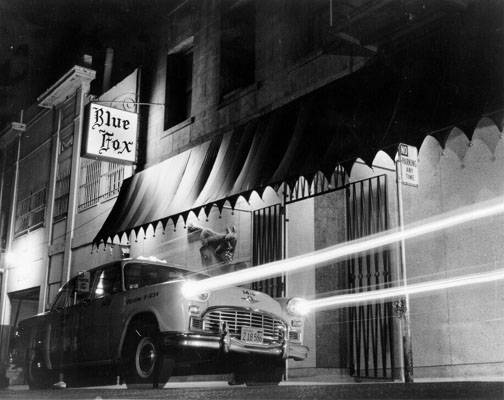

Blue Fox restaurant on Merchant Alley, 1960s, a short distance from where the bomb was planted.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

What were you doing at this time?

I would go down and plant the weapon in the general area. At that time the area was so congested I could just walk anywhere and lie the weapon down. Not for detonation, just lay it down. In other words, hide it . . . take it from the park and hide it again. Just temporarily hide it again . . . move it . . .to begin the motion of the action.

So I hid it at the construction site, not inside but in the debris. The plan was: I .would walk down to the end of the alley and back up again—and then I would retrieve the weapon, plant it and proceed up the alley and institute the get-away.

As I passed the first time, I realized the wooden door was open to the rear garage of the military police station. Immediately inside the garage is an area in which vehicles park, both civilian and military. From there you can see a locker room which we thought was used to store the gear—the guns and weapons and whatever—of the pigs working in that station. So when I made my trip down the alley, I decided it would be the best place. . . because I noticed these trash bins standing inside the doorway. So I came by the second time (on my first trip I saw there was no one inside) and I picked up the weapon and treated the weapon and put it in the trash can. Now as I was coming up here with the weapon and getting closer and closer to the spot itself, this woman was in constant visual contact' with me. If she signaled me that there was some foul-up or some police or some civilians in the area, the plan would be temporarily delayed: And delayed in such a way that it would be impossible to pin it on somebody. As I came up she gave me the clear signal. I was hurrying at that time, I was really moving, and I got to it; you know, and I put the device inside the door . . . inside the trash can.

The device we used wasn't particularly accurate, but we knew we had enough time. It's the kind of timing device which I'd prefer not to talk about. So the device was placed inside the trash bin and I began to run. Part of the plan was that I would exit the area on foot to the get-away car. The woman would go to one car, the nearest car, and she was to start the engine on that car and be ready to leave. The other man with us was to drive the second car, which was immediately in front of hers. Then we'd escape up the one-way street so if any civilians or military were to come behind us or follow us or in any way detect what was going on, she would be able to block that road, which would make it almost impossib1e for anyone to apprehend us at that point.

Now after the action, where did you all go?

The first thing we did was to leave the area. Then we parked the car that I escaped in, and changed into the second car and we went back to one of our places, where we discussed it. The first thing we did was. . . we were all nervous and blown-out, it was our first major action. . . we got high. We turned on the radio and we sat back. Of course we were pretty anxious to hear about it, though we were pretty certain the device had detonated because we had practiced with it before and the person who was responsible for it said it was perfect.

Did you reach any conclusions while waiting to hear news of the action?

We were basically interested in how to use our violence, how to use our attacks to mobilize other people. See, we don't think that we, alone can seize power or take over this country. We feel it's going to come through a large, massive movement. Our responsibility as people who realize this is to pick these targets and people to pull off these actions successfully . . . and to try and convince other people to follow our patterns. . . our style. We're experimenting—we're scientists. We're trying to develop a pattern, a style, to develop an understanding. We're willing to make certain sacrifices. We're willing to go out and do this. Now if we are to be criticized by the people, if our actions are inappropriate—then we deserve to desist, to disorganize ourselves. But until that point we feel that we have a certain role to go out and forge and create some new direction.

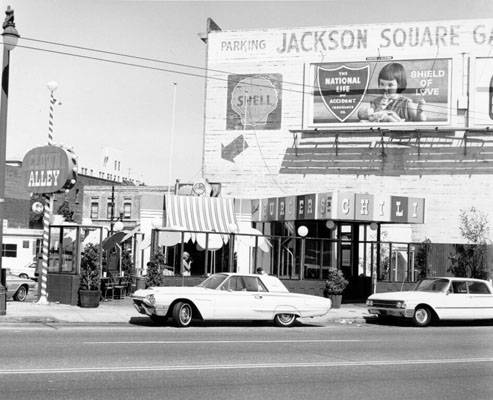

Clown Alley hamburger shop on Columbus Avenue, a short distance from the police station.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Is there a piece of information that you could relate to me that would in some way authenticate this interview? Something that did not come out in the press; or something that you remember about the action?

One thing I remember that was very ironic was that in the process of surveillance and reconnaissance, I saw a hamburger stand in the area that's called Clown Alley. And as I went to the trash can to plant this thing I saw all this shit coming out from Clown Alley. All this, you know, cups and stuff and trash from Clown Alley. . . and there was a beer can, I know it was a Lucky Lager because I happen to drink a Lucky Lager myself sometimes. I'm sure that whoever was, in charge of that investigation, if they investigated that trash in that barrel, which I'm sure they did, I'm sure they would find plenty of paraphernalia from Clown Alley and plenty of beer cans. Which is surprising—the pigs inside that station are drinking beer when they're on duty. I'd like to call for an investigation of those pigs.

I'd just like to know when you finally heard news of your action? Was it that night? What did it feel like?

That night the news wasn't going so well, it was late and the news didn't have it. We basically listened to FM stations and rock stations and they weren't carrying it. So we actually found out the next morning. It was in the paper. Which was also a great feeling to read about your action in the paper. We definitely began to understand the thing about mad bombers and people that are into this. There is a kind of ecstasy in knowing that you destroyed something, that you were effective. Because all of your life you are told that you can't get away with it, you can't beat it, and we beat it.