Archie Green and New Labor History

Historical Essay

by Sean Burns, November 2011

Archie Green (1917-2009) was a shipwright turned folklorist and labor historian who lived much of his adult life in San Francisco. In 2007, the Library of Congress awarded Green the “Living Legend Award” for his sustained dedication to the preservation of workers’ culture including his essential contribution to the founding of the American Folklife Center in the mid-1970s.

The child of Ukrainian immigrants, Green graduated from UC Berkeley in 1939, and shortly after began working in the Bay Area’s bustling ship building industry in the ramp up to World War II. His exposure to workers’ culture and a particular vein of Wobbly influenced, left-anticommunist, syndicalism led him to take up the study of labor history and workers’ culture—notably the songs of workers—as a hobby. In 1959, he parlayed this long time hobby into a professional career as a folklorist and labor historian. In 1972, University of Illinois published Green’s breakthrough book Only A Miner: Studies in Recorded Coal Mining Song, and, over the course of the next four decades he prolifically published in a wide range of disciplines including labor history, folklore, American Studies, ethnomusicology, and cultural studies. In the tradition of Benjamin Botkin, Green was widely heralded as the “Dean of Public Folklore” and his creation of the Fund for Labor Culture and History helps support the next generation of “laborlorists”—a term Green coined early in his studies. In the Bay Area, many generations of carpenters, pile butts, and sailors remember him as a colorful and tireless advocate of workers’ dignity and the value of labor.

Photo: Carl Fleischhauer

The following essay is an excerpt from my biography of Green, Archie Green: The Making of a Working Class Hero (p. 118-122, University of Illinois Press, 2011). The essay summarizes some of the key insights which Green—formatively shaped by the broader ethos of the “Age of the CIO”—brought to the early percolations of “New Labor History.”

Archie was there before any of us were.(1)

—David Whisnant, historian

In 1959, when Bernie Karsh recruited Green for a job in the Industrial Relations Library at the University of Illinois, Urbana/Champaign, it was on the strength of his knowledge of labor history and worker culture. Once in Urbana, Green efficiently handled his library duties and devoted much of his energy and time to directing the hugely popular student Folksong Club. This combination of employment gave Green, for the first half of the 1960s, a unique platform to build upon his research into the connection between labor song and labor history. During school breaks Green would frequently join other aficionados of old time music such as Ed Kahn and Norm Cohen on lengthy road trips in hopes of locating obscure hillbilly musicians who, in some cases, had not recorded or performed in decades. Drawing from such research, Green began his lifelong practice of prolific publishing. In the early 1960s, he wrote articles for regional magazines, essays for academic journals, and a steady number of liner notes for the burgeoning folk record industry. By 1966, through seminal articles like “The Death of Mother Jones” and “Hillbilly Music: Source and Symbol,” Green had made a name for himself in the American Folklore Society and larger folk revival circles.(2) The initial conference presentation and subsequent publishing of his paper, “Hillbilly Music: Source and Symbol,” was particularly significant in firmly establishing hillbilly music as a fecund and academically legitimate area of study for folklorists. Encouraged by this influence, Green decided to enter University of Pennsylvania’s doctoral program in Folklore in order to deepen his studies and lend authority to his scholarly contributions. Taking a leave of absence from Illinois, Green began doctoral work under the supervision of Professor MacEdward Leach—one of the few ballad scholars at the time who encouraged his unorthodox historical work.(3)

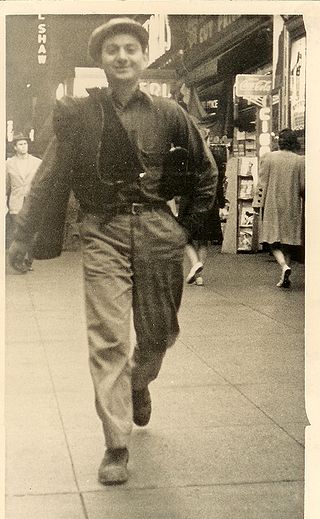

Archie heading to work on Market St. 1942

Green’s dissertation on recorded coal-mining songs became the groundbreaking book Only a Miner. University of Illinois Press published the first edition in 1972 as the inaugural study in its’ “Music in American Life” series. To date, the respected series includes almost one hundred and fifty books covering nearly every genre of popular and vernacular music in the context of the communities and histories from which they have emerged. Green recognized that Only a Miner advanced, through both scope of inquiry and methodology, beyond traditional disciplinary boundaries. “Many scholars,” he asserts in the book, “place no importance on the intimate relationship of the disciplines of folklore and history. But even folklorists (like [George] Korson) and historians (like [Philip] Foner) who clearly understand the relationship find it difficult to blend disciplinary skills.” As a corrective, Green proposed an “integrated historical-folkloric technique -– one that assumes…that folk composers and formal historians both cope with narrative art [and that] not only [is] the folk ballad a historical document but that the historian is also a special kind of singer of tales.”(4)

In Only a Miner, song study becomes a portal into the complex intersections of technological development, worker migration, Appalachian history, social movement study, artist biography, record industry history, shifting race and gender relations, prison history, and the formation of working class identities. In short, the book, which I read as representative of Green’s larger laborlore project, expresses and foreshadows many of the intellectual and political commitments of two, emergent and related scholarly transformations of the day: the rise of New Labor History and the impact of cultural studies/ethnic studies on American Studies. This chapter focuses on how and why we should understand Green as a part of these transformations.

In a 1965 article, written with an uncharacteristically theoretical focus, we find Green posing questions ahead of their time: “Does a [scholar] station himself at the furnace hearth, the personnel office, or the juke joint? Are our commitments strong enough to push us to steel not only where it is shaped physically, but also where the expressive life of its workers is shaped? It is entirely possible that future research in industrial culture will belong more to labor historians, industrial sociologists, or ethnic studies specialists than to folklorists.”(5) Green’s questions illustrate the disciplinary shift that would come to be known as writing “history from below” or, in academic parlance, New Labor History.(6)Before discussing Green’s specific contributions to New Labor History, let me briefly sketch how this broader movement to create “history from below” broke from the prevailing conventions of labor history at the time.

New Labor History’s emphasis on workers’ identity, workers’ culture, and workers’ struggles emerged as a response to the limitations of the “Wisconsin School” or “Commons School” of labor history. In the first half of the twentieth century, labor studies was practiced as a subset of economics, and the leading proponent was Professor John R. Commons at University of Wisconsin-Madison. Recall that Green’s favorite professors at UC Berkeley, Paul Taylor and Ira Cross, identified with the Wisconsin school. The school focused on labor’s institutional history through studies of unions, union leadership, and major labor strikes. These studies looked favorably upon trade unionism in so far as they saw it as a stabilizing factor for capitalism’s continuation. Whereas Wobblies and Marxists had long seen inherent antagonism in the worker/employer relationship, the Wisconsin School believed in the possibility of a broad worker/employer consensus. Their labor scholarship reflected this political commitment.

By the late 1950s and early 1960s, a number of young U.S. based scholars, the best known of which are Herbert Gutman and David Montgomery, began developing different approaches to labor history. Deeply influenced by E.P. Thompson, Christopher Hill and other British Marxist Historians, these scholars took up labor studies from the disciplinary perspective of social history, using the analytical tools of historians. In itself, this was a generative break from the questions and methods of economic history. Their early work moved the core concerns of the field away from institutional labor history toward working class history—a shift reflective of how their radical readings of capitalism differed from the liberal views of the Wisconsin School.(7) A generation of student activists from the New Left poured into graduate schools in the late 1960s and early 1970s further propelling this scholarly interest in uncovering workers’ struggles and cultures. Often emerging from passionate engagement in the Civil Rights, anti-Vietnam War, and women’s movements, these students developed new perspectives on the working class, the development of oppositional cultures, and the dynamics of social change.

Archie and wife Louanne 1941

Central to these shifts was an expanded conception of where one could find “the worker” and, by extension, an expanded conception of what kinds of social-historical materials could be looked at to illuminate worker identity, culture, consciousness, and struggle. In this respect, “history from below” posed challenges to both Marxist and liberal assumptions about the working class. New Labor Historians saw that politics dwells in, congeals around, and emanates from places and identities unmapped and undetermined by economic modes and relations of production. Transcripts of union meetings might still be significant, but they were no longer sufficient. The politics of the everyday, to use a popular and revealing phrase, started to become an important historical concern.

It is no wonder that New Labor History began to draw heavily from folklore studies. With their long history of ethnographic fieldwork, folklorists have been the people most meticulously documenting the speech, rituals, songs, jokes, fashions, and visual art of people living their everyday lives in their everyday contexts at work, at home, and in public. Yet, despite the centrality of folklife to the intellectual and political vision of “history from below,” folklorists themselves have been inadequately recognized in the commonly circulated origin stories of New Labor History. The absence of Archie Green from standard historiographies of New Labor History is a case in point.(8) In 1965, when Green encouraged labor historians to look beyond the parameters of the work place and examine the fuller cultural life of workers, he had not yet heard of E.P. Thompson, Herbert Gutman, or David Montgomery. It is in the next ten years that these historians’ writings would become widely available and influential—the same years that Only a Miner began to circulate.(9) Interestingly, Green’s book was never reviewed by any labor history journal. It was not even mentioned in the United Mine Workers periodical. Yet it almost immediately became a revered, founding document for the nascent field of Appalachian Studies.(10)

My point is not just that we should add one more name to the list of founding (white) fathers of New Labor History. More fundamental than that I wish to bring attention to how the epistemological and methodological transformation of “history from below”—a transformation born of complex, far reaching, and often revolutionary social forces—has over time been reduced and disciplined into a short list of a handful of writers within the academy—however amazing their research. Remembering other influential tributaries in the origin story of New Labor History can make a difference for how we understand labor history’s current horizon of concerns and their political consequences. Bringing Green and others into historical view is less about altering the past and more about rejuvenating and decalcifying current historical work.

As Robin D.G. Kelley’s Race Rebels makes clear, black historians W.E.B. Du Bois and C.L.R. James have also been insufficiently recognized as paramount to making the analytic, interdisciplinary connections through which New Labor History found life. Kelley helps us see, for example, how their absence might account for the overly white and Eurocentric focus of the first wave of New Labor Historians.(11) Similarly, David Roediger highlights how essential the work of George Rawick and Alexander Saxton should be to how we view the originating forces turning labor history toward workers’ culture.(12) Rawick drew from African-American slave studies and Saxton, Roediger noted, wrote many novels before embarking on his landmark The Rise and Fall of the White Republic.(13) Rethinking New Labor History should be done in light of all these intellectuals, not just Green.

Archie Green at home, 2006.

Photo: Michael Rauner

In Green’s case, when we sustain attention on his vision of laborlore, we are emboldened to resist the trend of New Labor History to conveniently fall back into asking questions and focusing on sources that defined the kind of history it originally set out to challenge. As has been noted, “Old” Wisconsin School labor history mostly stuck to institutional histories of unions and the famous men that led them. There was little room for worker experience, worker subjectivity, and worker folklife. Likewise, there was little attention paid to women, workers of color, and immigrants who have often labored under the most exploitive conditions. Green helped address these shortcomings through laborlore’s focus on cultural and worker subjectivity. Green’s concerns have not been embraced by all New Labor Historians. Roediger addresses these tensions when he says, “You would think that Archie’s studies about language—his word studies of fink, wobbly, scab, etc.—would be really interesting to labor historians. But this gets entangled in the minds of some labor historians with what they regard as an attack on materialism by the linguistic turn and cultural studies. Their idea that language studies always and inevitably take you away from material life, work, and oppression and gets you talking in an ethereal realm that never gets you back to class relationships. That’s just flat wrong. That’s not what Archie does at all.”(14)

For our purposes, a crucial development in New Labor History is this: when labor scholars began to seriously take up questions of workers’ culture, they were challenged to think in new ways about the role and place of workers’ voices in their projects. Whose voices are heard in history writing? These concerns necessitated fresh research methods and encouraged a democratization of the very processes of history making. These disciplinary transformations were not only about new subjects and hidden histories but also about letting workers speak for themselves. Archie Green helped direct this democratization process, not only because he embodied a link between labor history, folklore, oral history, and cultural studies, but also because he forged new inroads for workers’ culture in public history.

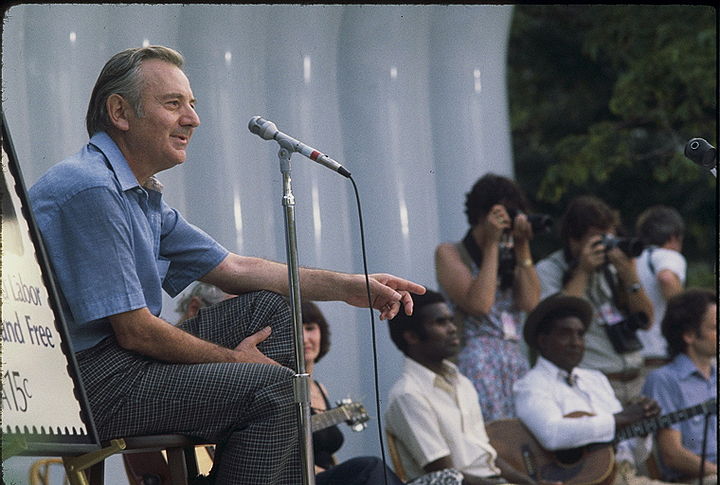

Archie Green speaking on Labor Day 1980 at the White House.

Photo: courtesy Sean Burns

Green’s initiation of the Working Americans exhibit in 1971 and his indefatigable commitment to the establishment of the American Folklife Center (1976) should be acknowledged as politically and historically related to other radically democratic projects of the era—think of Alice and Staughton Lynd’s 1981 publication of Rank and File: Personal Histories By Working-Class Organizers and Herbert Gutman’s initiation of the American Social History Project at CUNY in the same year.(15) It is Green’s experience as a worker, his syndicalist-rooted commitment to the dignity and intelligence of working people, that combined with his skills as an ethnographer and folk festival impresario to makes these interventions imaginable and manifest.

Notes:

1. Author interview with Whisnant, 9/6/06.

2. Green, “The Death of Mother Jones” and “Hillbilly Music: Source

and Symbol.”

3. Green also considered working under Wayland Hand (UCLA) or Bertrand

Bronson (UC Berkeley), but their West Coast locations made it logistically

difficult.

4. Green, Only a Miner, 170.

5. Green, “American Labor Lore: Its Meaning and Uses.”

6. “History from below” was originally coined by French social

historian Georges Lefebvre in his many books on the origins of the French

Revolution. British Marxist historians like E.P. Thompson, Christopher Hill,

Erich Hobsbawn, and Raphael Samuel popularized the notion, and it is through

their influence on American social historians that the concept became wedded

with New Labor History in the United States.

7. For an insightful reflection on the continuities and discontinuities

between New Labor History and the “Old Labor History” of the Wisconsin

School, see David Brody’s articles “The Old Labor History and the New”

and “Reconciling the Old Labor History and the New.” As I noted in

chapter one, p.54, Green studied under Ira Cross at UC Berkeley. Cross was a

well-known student of John Commons.

8. For two sources on the historiography of New Labor History, see David

Brody’s essays in the previous citation and MARHO, Visions of History.

9. E.P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class; Herbert

Gutman,Work, Culture, and Society in Industrializing America; David

Montgomery,Worker’s Control of Machine Production in the Nineteenth

Century.

10. Only a Miner was immediately reviewed in journals focused on music,

folklore, and anthropology as well as The Nation. Also, importantly,

Staughton Lynd reviewed it in The American Historical Review Vol. 78, No. 1

(Feb. 1973) 169-170. David Whisnant, one of central figures in the birth of

Appalachian Studies, has this to say about Green’s influence on the early

days of the field: “Everyone knew and respected Archie, and he talked with

them/us as he always did, with enthusiasm, amazing political insight, the

ability to make connections and draw conclusions no one else was making or

drawing, connecting people with each other, praising their work and helping

them to take the next step, helping us all to see the implications and

possibilities of what we were trying to do or might do.” Author’s notes.

11. Kelley, Race Rebels: Culture, Politics, and the Black Working Class, 6.

12. Author interview with Roediger, 9/29/06.

13. Saxton, The Rise and Fall of the White Republic; Rawick, ed. The

American Slave: A Composite Autobiography.

14. Author interview with Roediger, 9/29/06.

15. Lynd, Rank and File. The American Social History Project produced the

two volume Who Built America?: Working People and the Nation’s History and

today continues its work in collaboration with CUNY’s Center for Media and

Learning. [[category:1970s]