Ant Farm

Historical Essay

by Eli Alpern

Cadillac Ranch (1974)

All images in this article used with permission from Ant Farm 1968-1978 (Oakland: University of California Press, 2004)

| As experimental art, architecture, and design cemented the centrality of aesthetics in the counterculture of the 1960s and 70s, individuals and collectives that challenged societal and professional norms thrived. It was in this environment that Ant Farm, a group of “underground architects,” was formed in 1968. The collective travelled the country, documenting their experiments using the newly-accessible medium of portable video, hoping to provoke radical re-imaginings of the uses of space and modes of living. |

Art, architecture, and design played a central role in the thriving San Francisco Bay Area counterculture of the 1960s and 70s. These artistic efforts intersected with radical experiments in communal living, and new digital technologies, to challenge societal norms and create alternative life paths in a prefigurative spirit. Many collectives attempted to disrupt the purely aesthetic conception of hippies, seeking to create concrete change not only on the streets, but also in the classroom, at home, and even via government policy. The democratisation of tools and technologies, which foreshadowed the popularisation of open-source projects in Silicon Valley, enabled a communal ethos that supported a “web of affinities linking counterculture architects, planners, ecological activists, and educational reformers.”[1]

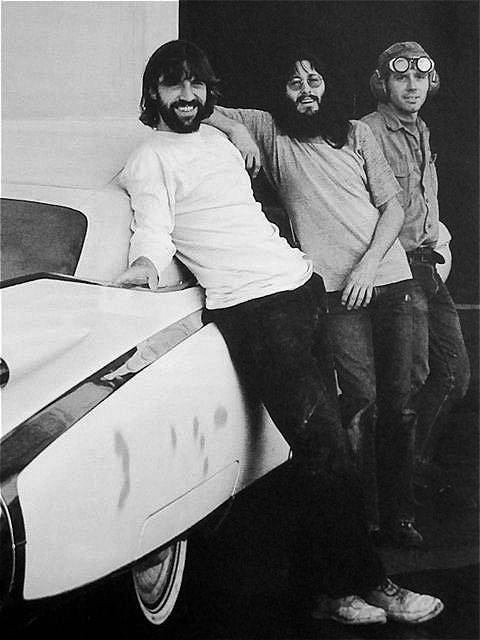

The Bay Area based Ant Farm boldly expressed this confluence. As a collective of “underground architects” who used the newly-accessible medium of film to document their experiments, Ant Farm attempted to place a quotidian concept of ‘earth awareness’ firmly in the public consciousness. Ant Farm was founded in 1968, a year after the Summer of Love and in the midst of the the denouement of the iconic Haight-Ashbury district era. Founders Doug Michels and Chip Lord, soon joined by Curtis Schreier, formed the base of the group. Michels, Lord, and Schreier were recent college graduates with degrees in architecture. In a 1968 interview, Chip Lord describes how, “there was revolution in the air,” and “nobody wanted to go to work in a corporate architecture office… a Bank of America was something you wanted to burn down, you didn’t want to be designing banks.”[2] With this sentiment, the group decided to work for themselves and call it an underground architecture practice.

Ant Farm’s core members, from left to right, Doug Michels, Chip Lord, and Curtis Schreier, San Francisco 1973

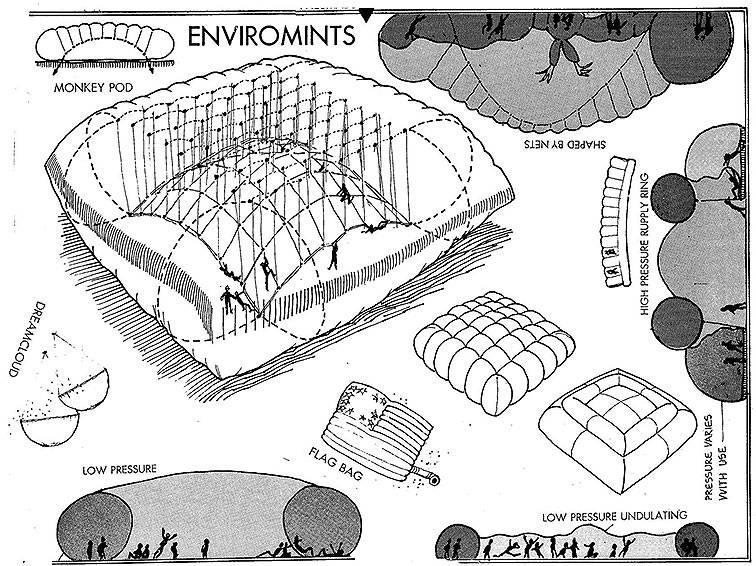

1970: Nomadic Inflatables

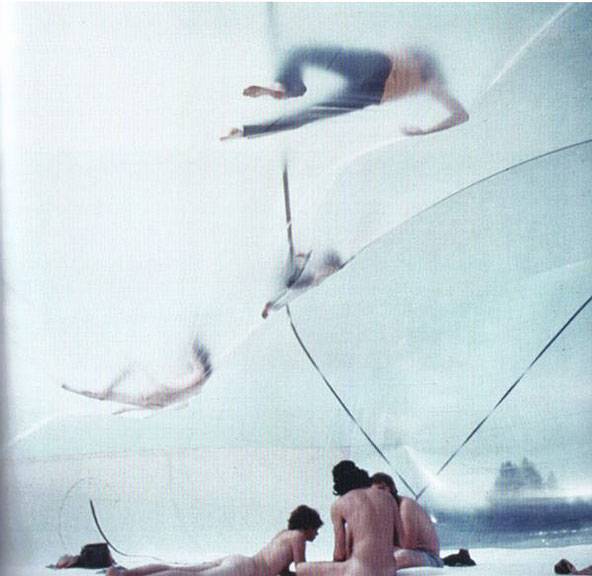

Ant Farm’s early works were mostly full of hot air….As in, they were heavily composed of self designed inflatables [3]. What started with experimentation with cargo parachutes became giant inflatable air “enviromints,” where people could either hang around inside, or play around on top. Chip Lord later realized that this was a direct response to brutalism, the dominant rectangular concrete behemoth architecture of the times. The balloonish “dreamcloud” architecture was described by the artists and the people who experienced it as temporary, nomadic, malleable, and even sensual. One French critic likened inflatables to a softening erection. [4] They set these huge bubbles up in a variety of unexpected places such as deserts, parking lots, concerts, and college campuses. In the communal culture of the time, festival venues would become short term cities, and the inflatables made people imagine new, utopian architectural possibilities. While “right angle architecture” was bound by limits and laws, inflatables allowed a new dimension to take place where there are no rules.

Besides using these inflatables to provoke a reimagining of how the world could be better, Ant Farm also used new tools to show how it could be worse in more direct political performances. On the first Earth day, 1970, they set up an inflatable on Sproul Plaza at UC Berkeley, in the same place where the Free Speech Movement had been born only 6 years earlier. The giant bubble, labeled “F310 clean air pod,” was said to provide clean, filtered air. The members of Ant Farm stood outside of the balloon with gas masks on, and over loud speakers declared an air emergency, warning passersby to get in for their safety. [5] In this agit-prop performance, the inflatable was a tool for promoting environmental consciousness, and providing a powerful image for what pollution was leading to. Ironically, their gas powered fans and materials weren’t exactly eco-friendly, but they recognized this, and made the point that their footprint was much less than the construction of a concrete building, and they hoped that future generations would find more environmentally friendly materials to work with. Ultimately, their goal was to make people think about the endangered environment, and their symbolic images sought to do just this. The environmental movement would have great legislative success in the early 70s with laws like the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts becoming law under Nixon!

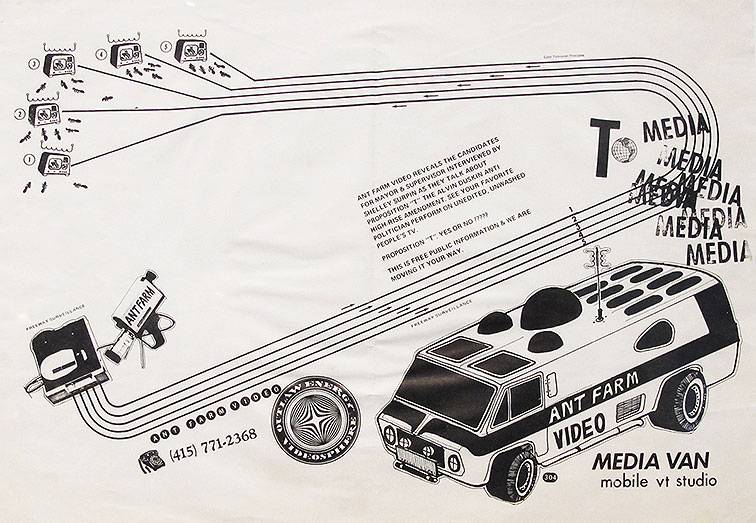

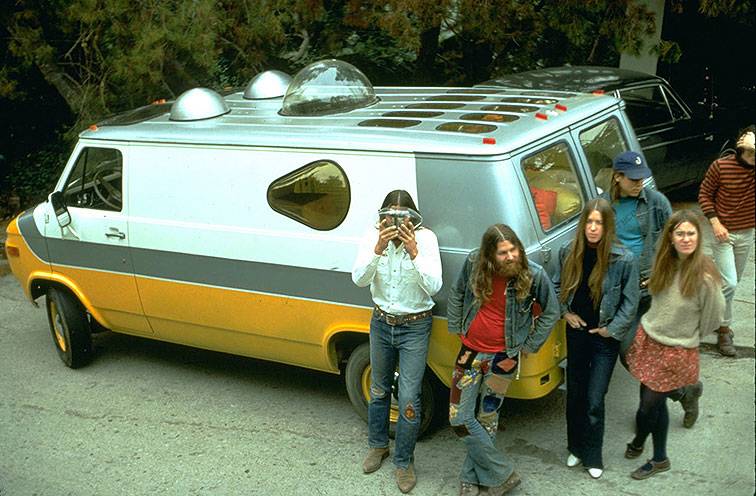

1970: Media Van

Around the same time that Ant Farm was starting up, the Sony Portapak (pictured above) hit the market. This handheld camera was self-contained and battery-powered and could be held by one person, which was a new ability at the time. As Chip Lord put it, there was a feeling that “If we claim the tools somehow we could influence the discourse.”[6] When Ant Farm got their hands on these new portable cameras and used their skills to customize a van to travel the country in, the “Media Van” was born.

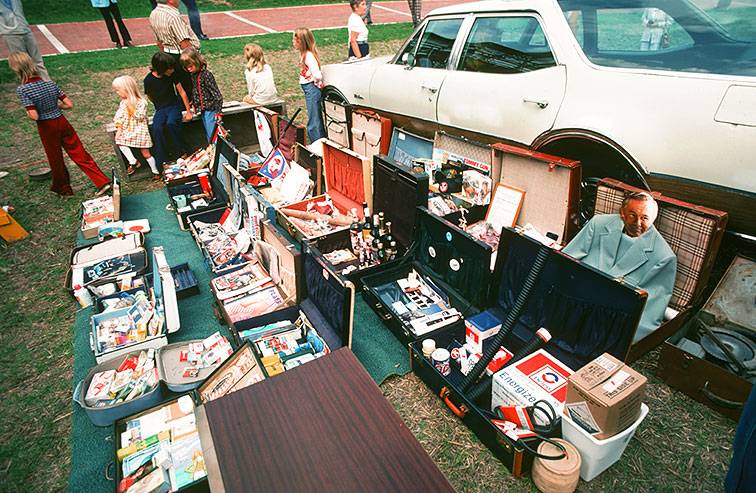

As Ant Farm cruised around the country, they produced a map called the Truckstop Network that could be used by other travelers to find hives of hippy activity. [7] Their Media Van had a futuristic design, and they recorded their traveling experiences and social experiments. One film, World’s Longest Bridge, is simply that: a 24 minute, real time shot of Ant Farm driving the Media Van across what’s advertised to be the longest bridge in the world (the Lake Pontchartrain Causeway). Another film is called Dirty Dishes, in which the members of Ant Farm, and some friends on the road, eat meals, make jokes and ask questions. But even after they started traveling and shifting their focus more towards filmmaking, they continued to enact sculptural social interventions. One of their most famous projects is called Cadillac Ranch (1974), which can still be seen from the highway in Texas (the image opens this article). They were also commissioned to build a house on a lake in Texas, which they designed and called The House of the Century (1972), as well as many different time capsules (1972):

Ant Farm’s artistic endeavors were wide-ranging to say the least, but the video camera served as a connector. The group’s later work was especially focused on filmmaking. They worked with other similar groups of the time like TVTV, Optic Nerve, the Videofreex, TR Uthco and others. One of their most famous movies is The Eternal Frame (1975), in which they reenact the JFK assassination with the same impersonator from Media Burn, Doug Hall of TR Uthco. This avant-garde film shocked and confused people, but wasn’t nearly as widely circulated as images from their “Media Burn” that took place the same year - also involving President Kennedy.

1975: Media Burn

On July 4th, 1975, President John F. Kennedy, more than ten years after his death, gave a famous speech in which he explained that “mass media monopolies” controlled the flow of information, and thus controlled the people in a “nation addicted to media.” The deceased president then posed the question: “Now I ask you, my fellow Americans, haven’t you ever wanted to put your foot through your television screen?”[8] Of course, this wasn’t the real JFK. The impersonator and his speech were part of a performance by a group of artists. The “artist-president”, as he was labeled, was introducing what was dubbed the “ultimate media event.”

Weeks earlier, news crews around the Bay Area received a press release that declared: “On July 4th, 1975 members of Ant Farm will drive a Phantom Dream Car thru a wall of burning television sets in an event called MEDIA BURN.” Media crews showed up with their “official press passes” to cover the event, but they had no idea what they were in for. The Artist-President ended his speech with: “The world may never understand what was done here today, but the image created here, shall never be forgotten.” After some scattered cheers from a few hippies in the small audience and of course, the national anthem, two “media matadors” a.k.a. “artist-dummies,” drove a customized, futurized, 1959 Cadillac El Dorado Biarritz through a pyramid of burning TV sets to create an unforgettable 20th century image:

The media didn’t seem to understand this anti-television event (surprise!), as anchors deemed it “weird” and “over our heads,” and thus, its immediate impact was underwhelming. But the footage from the event and the media’s coverage of it was edited into a thought-provoking film, available online here. The iconic still photograph spread as a popular postcard, standing as a “visual manifesto” for the anti-network-television freelance filmmakers of the time.

1978: Media Burned

Three years after Media Burn, in 1978, a fire started in Ant Farm’s studio, and much of their media was destroyed. This, along with the demise of the hippie era, marked the end of Ant Farm. Fortunately, not all of their material was destroyed, and many of their images have been recently digitized at the Berkeley Art Museum / Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA). Ant Farm’s work figured prominently in the 2017 Hippie Modernism Exhibit at BAMPFA which has travelled to multiple museums across the United States including the Walker Art Center.

Notes

[1] Lewallen, Constance M. and Steve Seid, Ant Farm 1968-1978 (Oakland: University of California Press, 2004).

[2] Castillo, Greg. “Counterculture Terroir: California’s Hippie Enterprise Zone” in Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia (exhibit catalogue) 2015.

[3] Federici, Beth and Laura Harrison (directors). Space, Land and Time: Underground Adventures with Ant Farm. 2010. DVD.

[4] Castillo, 2015.

[5] Space, Land and Time: Underground Adventures with Ant Farm. Dir. Beth Federici and Laura Harrison. Perf. Ant Farm. 2010. DVD.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Lewallen, Constance M. and Seid, 2004.

[9] Ant Farm, Media Burn (1975).

Bibliography:

[1] Media Burn, original film by Ant Farm, 1975

[2] Counterculture Terroir: California’s Hippie Enterprise Zone, Greg Castillo, 2015

[3] Ant Farm 1968-1978

⎼By Constance M. Lewallen and Steve Seid ; with additional essays by Chip Lord, Caroline Maniaque, and Michael Sorkin ; and a timeline by Ant Farm.

Berkeley : University of California Press, © 2004.

[4] Space, Land and Time: Underground Adventures with Ant Farm. Dir. Beth Federici and Laura Harrison. Perf. Ant Farm. 2010. DVD.