A Round of Drinks for the Good Richard Knight

Historical Essay

by Mike Mosher, 2009

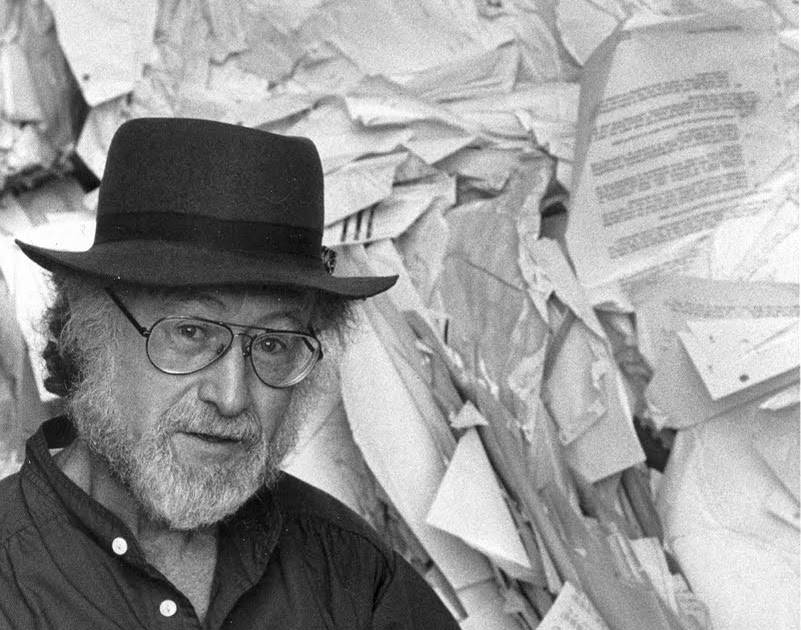

Richard Gamble Knight

Photo: courtesy Richard Gamble Knight blog

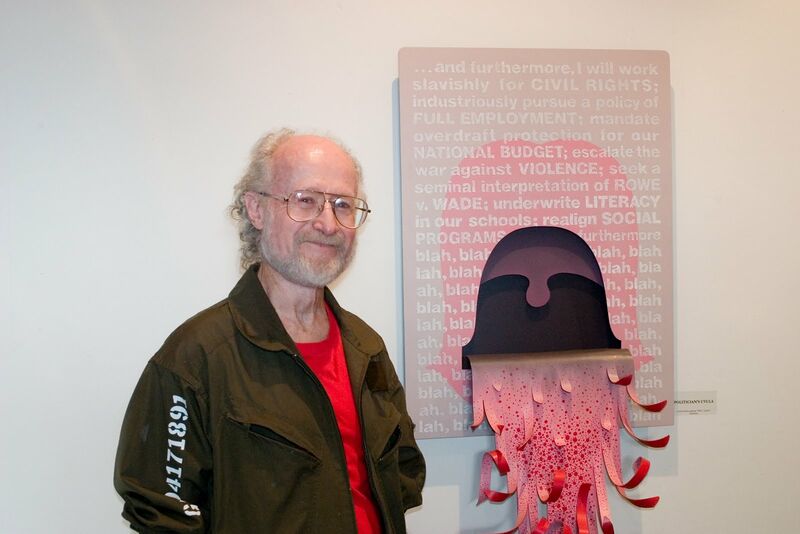

Richard Knight, June 2004

Photo: courtesy Richard Gamble Knight blog

I have been thinking a lot about the artist Richard Knight since his death in December 2008, a few days after his eighty-second birthday. He left us elegant and witty artwork, and examples of a good life and even a good death. And, like many, his was one more story of San Francisco as an arena for personal reinvention.

When Richard Knight appeared in San Francisco about 1981, he was suddenly one of the coolest guys around. Art curator Bob Hanamura, whose presence at any art event indicated it was the hip place to be, introduced Richard as one more recent exile from Michigan. At about age fifty, Richard had left a soured marriage and career as an architect for adventure on the west coast, and found himself in my own crowd of twenty-something SF State grad students of Painting, miscellaneous artists, songwriters and punk rockers.

He first lived on Potrero Hill until he found a former bar on Third street, then an industrial area called "Dogpatch", before rickety lawyer lofts went up in the 1990s. He filled the space with artwork, his own sculptures completed or in progress, plus fine photographs and old billboard graphics on the walls. Massive ladder-back chairs made out of steel and lumber surrounded his busy dining table. Ever one for the dada pun, he created a "newspaper column" by positioning stacked newspapers around the support pillar the middle of his space. His work of the last decade was characterized by aluminum ribbons, bent elegantly, movement frozen in metal. A metal flag with skeptical text commemorated 9/11, one of his most overtly political works but also, paradoxically, one of his loveliest.

Richard Knight at an opening for his art in Los Gatos.

Photo: courtesy Richard Gamble Knight blog

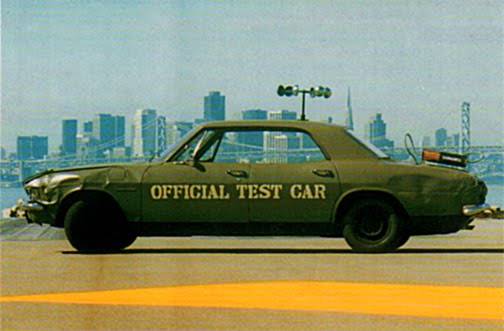

Official Test Car

Photo: courtesy Richard Gamble Knight blog

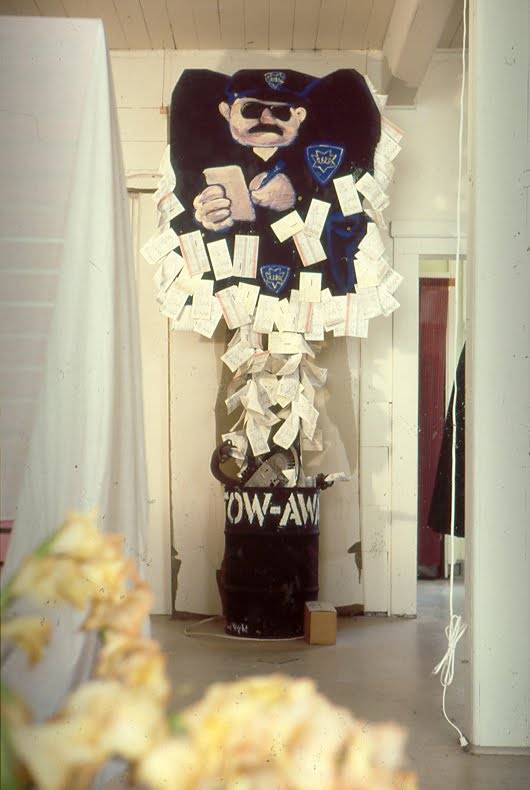

He refashioned an old Corvair that he inherited from his mother into his "official test car," painting it in portentious gray-green primer, stencilling on some cryptic numbers, and mounting a large, rotating wind-measuring anenometer (actually, no more functional than the propeller on a beanie hat) in the center of the roof. Richard and I even collaborated on a project about thirty years ago, an "urban scarecrow" for a competition at a San Francisco County Fair. With plywood, a beam and a 55-gallon drum fished out of the dump behind his studio, plus several dozen parking tickets supplied by SoMa restauranteur Mark Rennie, we assembled a scowling moustachioed cop, the tickets stapled to his body like feathery plumage. Richard called it "The Ticketron".

The Ticketron

Photo: courtesy Richard Gamble Knight blog

Richard drew upon his architectural background for some projects, and briefly taught interior design at the Academy of Art College. A small shrine for Buddhist mediation that he built of Fom-Cor had tiny figures at the bottom, that turned it into a maquette for a multi-story tower. He consulted on the ILWU mural-sculpture in its early stages, but was dissatisfied with the ultimate results. He once proposed a mammoth Gateway to the Mission, to be erected where Van Ness and Mission Streets intersect, upon which I was to paint murals of appropriate neighborhood imagery. His plan for the butt-end of the Embarcadero Freeway a waterfall that could serve as a free shower for the homeless population, and his insouciant little ink drawing of the idea appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle.

While there were raucous parties in my Clarion Alley studio, our art gang also convened in various Mission and Bernal Heights neighborhood bars. I can’t remember the name of the favorite place on Army (now Cesar Chavez), but other evenings of big ideas, local gossip, wit and sparkling talk took place at the Rite Spot on Folsom, the Circle Club on Valencia, the Nock Nock on Haight, and a friendly women’s bar on Richland that one Marie Laurencin-like painter suggested. In those days, I occasionally tended bar at Patrick Nolan’s Dovre Club, a mordant and macho place occupying the corner of the mural-bedecked Women’s Building, so several gatherings took place there.

Richard was a prankster. One night when drinking at the Dolphin P. Rempp Ship Restaurant near China Basin, there were limousine races going on, teams of collegiates stopping at various points, having a drink, taking their receipt and moving on. Richard and another reprobate piled into one of the waiting limos, and when the driver turned around and said "Hey, you’re not the guys I dropped off", Richard replied sotto voce, "Oh wait, maybe you’re the wrong limo".

In the late 1980s he took up with laughing Judith Lynch, whom he later married, his companion to the end. He was especially excited by a video she had made of the electrocution of a pickle, indicative of the goofy sense of humor that helped win his heart. They moved to Alameda, and he continued making his sculpture, exhibiting on the peninsula and elsewhere.

He also plugged back into his Michigan life, when Judith encouraged him to assemble his archive of fifty-year-old photographs from an early job in the studio of the architect Eero Saarinen into a book, which was published by William Stout Publishers. My university’s gallery held a show of his sculptures in Fall, 2007, and while in the midwest, he introduced himself to Cranbrook Art Center just north of Detroit. As they had scheduled a Saarinen exhibit, Cranbrook promptly invited him to exhibit his photographs, and to speak at a seminar discussing Saarinen and his work. As he rose to speak at the seminar, friends noticed Richard wore a pair of brightly-colored, and mismatched, socks. A glimpse into the front row of the audience showed that Judith was wearing the same color scheme, their mates.

After that year of professional success, some cancer that had been brewing (about which he had been cagey and didn’t want to talk about) started to get the best of him. After Judith said something in an email about hospice care, I gave him a call, and managed to catch him on his birthday. His family was gathered around, and I could hear his smile through the phone line as he said weakly "Hey, life is good."

Yet we ended up disagreeing on a theological point. One night, shortly after Pat Nolan died in the 1990s, I dreamt of Heaven as a resplendent barroom, where effusive publican Nolan presided and served everyone throughout history you’d ever want to meet. That’s remained my consoling vision of the afterlife, so as what I knew would be my last conversation with Richard was wrapping up, I said "Richard, we’ll all meet again at the Dovre Club." He paused, perhaps remembering the early 1980s more clearly than I, and muttered "Yeah, well, I don’t know about that dive...".

Community muralist Mike Mosher lived in San Francisco and the Bay Area 1978-2000. He now teaches art and digital media at Saginaw Valley State University in Michigan.