For Whom the Belle Toils

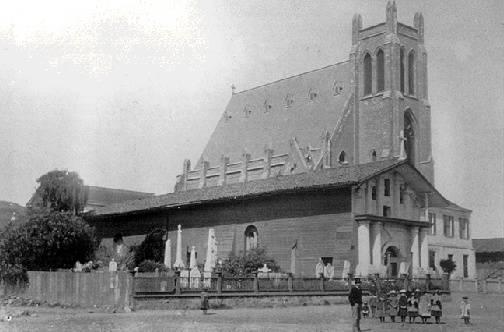

Mission Dolores in 1876 Photo: Greg Gaar Collection

The Graves of a Lynched Gambler and the Whore-mistress who Loved Him. Mission Dolores Cemetery. Enter through Mission Dolores, on Dolores Street at 16th. Hours: 9-4:30, May through October; 10-4, November through April. Open 7 days (call for holiday hours.) Phone (415) 621-8203.

San Francisco's most hallowed ground, the tiny graveyard behind Mission Dolores, is the final resting place of the Gold Rush era's most notorious madam, Belle Cora, and her gambler lover, Charles Cora, whom she finally married two hours before his neck was stretched by the Vigilance Committee. Their fall--Cora's from a scaffold, and Belle's from grace--marked the end of an era: No longer would wide-open, rip-roarin' gamblin' and whorin', with its attendant shootings and lootings, be allowed to flourish quite as openly as it had during the first five years of the Gold Rush.

From 1852 until 1855, Belle Cora, whoremistress extraordinaire, was queen of the City's social roost. She had arrived from New Orleans in 1849 with her gambler consort Charles, and the two of them had toured the gold country boom towns, amassing a fortune from their respective specialties, prostitution and gambling. By 1853, Belle was the City's premiere madam. Her sumptuous parlor house at Dupont and Washington streets offered the most beautiful women that money could buy; her prices were the City's highest; and her customers included most of San Francisco's leading citizens. Belle was known as the most expensively dressed woman in town, while Charles Cora was said to have a net worth of around $400,000, a not inconsiderable fortune in those days. Together, they moved unimpeded through polite society--until the fateful evening of November 15, 1855.

On that date, the two of them attended the opening of the American Theatre's new play, Nicodemus; or The Unfortunate Fisherman, seating themselves (as usual) in the first balcony--the most expensive, most prestigious seats in the house, in full view of the socially-conscious public. When the intermission came and the house lights went on, some men in the pit turned toward the notorious couple, laughing and pointing their fingers. A Mrs. William Richardson, wife of the U.S. Marshall, who happened to be sitting just behind the Coras, at first thought herself the object of all this boisterous attention. Offended, she complained to her husband. When the Marshall discovered the true cause of the hubbub in the pit, he accosted the Coras and insisted that they leave. When the Cora's refused, and the management wouldn't eject them, Marshall and Mrs. Richardson stalked out of the theater.

The incident, which would seal the fate of both men, symbolized the social changes that were sweeping over San Francisco. During the Gold Rush, gambling and prostitution were mainstays of the City's life; the first City Hall was placed next to, and dwarfed by, San Francisco's largest and most notorious gambling den (see photo), and the few women in town, most of them prostitutes, were highly esteemed despite (or because of) their profession. As Albert Benard then put it, "There are also some honest women in San Francisco, but not very many." But by 1854, the Gold Rush had petered out, respectable women were arriving in large numbers, and more and more citizens wanted to lend the City "class" by ridding it of crime and sleaze. The first laws banning gambling and prostitution were passed in 1854, and though the former vice was suppressed somewhat more energetically than the latter, the main effect was psychological: The era of open, officially-sanctioned wickedness was over.

The day after the flare-up in the theater, Richardson ran into Cora twice, first in the street, later in the Cosmopolitan saloon. Words were exchanged, attempts at reconciliation were made by mutual acquaintances, drinks were ordered, more words were exchanged. The following afternoon, Richardson lit out on a hunt for Cora, stopping in saloon after saloon and loudly proclaiming a thirst for vengeance that rivaled his legendary appetite for drink. (Whether he was armed is still a matter of dispute.) But when he ran into Cora on the street, Richardson apparently forgave him, and they drank together in seeming harmony, visiting two saloons together before parting company. Two hours later, Richardson again accosted Cora, this time in front of Montgomery Street's Blue Wing Saloon. They talked, turned, and walked down Clay Street to the corner of Clay and Leidesdorff, where--under circumstances that remain murky to this day--Charles Cora shot and killed US Marshall William Richardson.

One version has it that Cora slammed Richardson against a building, pinning his arms, and, as Richardson screamed "Don't shoot! I'm unarmed," Cora shot him in cold blood. Another version: Cora collared Richardson, Richardson reached for his weapon, and Cora fired first in self-defense. In either case, a notorious gambler, the consort of the City's most infamous madam, had shot and killed a US Marshall, and partisans of law, order, and respectability were not amused. They were even less amused when, during the trial, the prosecution claimed that Belle Cora done her best to bribe and intimidate a witness. It soon became apparent that Belle, as much as Charles, was on trial. The San Francisco Argus raged that "the harlot who instigated the murder of Richardson, with others of her kind, are allowed to visit the theaters and seat themselves side by side with the wives and daughters of our citizens." Imagine the public outcry, then, when a brilliant speech by defense attorney Colonel E.D. Baker compared Belle to Mary Magdalene . . .and provoked a hung jury. (Some whispered--and the newspapers shouted--that bribes dispensed by Belle and her confederates may have contributed to that outcome.) Though Charles Cora remained in jail awaiting a second trial, few believed he would ever be convicted. Then, in the late afternoon of May 14th, 1856, City Supervisor James Casey shot crusading newspaper editor James King of William, touching off a rebirth of vigilantism in San Francisco. On Sunday, May 18th, 2,600 Vigilantes surrounded the jail where Cora and Casey were housed and demanded that the Sheriff surrender the prisoners. The Vigilantes, armed with a cannon as well as shotguns, rifles, swords, knives, and revolvers, had Sheriff David Scannell and his thirty men badly outgunned. The Sheriff handed over Casey and, after a brief argument, Cora. (The clincher came when the Vigilantes loaded their cannon and stepped aside, leaving a clear firing lane between the weapon and the jailhouse door.)

The Vigilance Committee re-staged Cora's trial, only this time without a real defense attorney; his "counsel" was chosen from among the Vigilantes. Still, it was not a terribly unfair trial, at least by standards of vigilante justice. At the end, a bare majority voted for conviction of Cora (Casey was convicted unanimously) and the two men were sentenced to hang.

On Thursday, May 22nd, 1856, Belle Cora learned of her lover's impending execution. Hurrying to "Fort Gunnybags," the Vigilante jail, she convinced the Vigilantes to let her stay with Cora for the rest of his natural life. Late that morning they were married; at 1:21 that afternoon church bells rang out King of William's funeral. As the bells chimed, a platform was yanked from beneath Cora and Casey and the two men dangled, jerking spastically, until the last drop of life gurgled from their throats.

--Dr. Weirde

File:Mission$mission-dolores-1875.jpg

Mission Dolores in 1875 Photo: Greg Gaar Collection

excerpted from A Guide to Mysterious San Francisco: Dr. Weirde's Weirde Tours