Coit Tower Politics

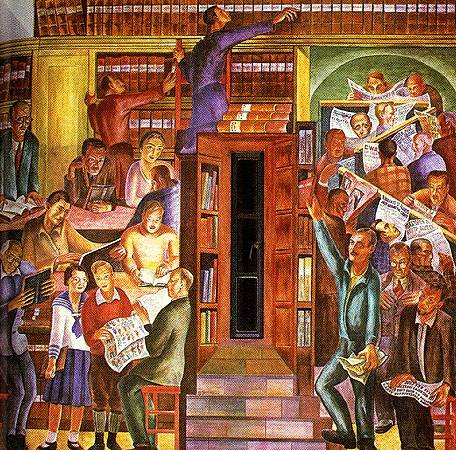

Coit Tower Mural (Library by Victor Arnautoff)

With great enthusiasm, the artists went to work at Coit Tower at the beginning of January 1934. An editorial in the San Francisco Chronicle noted that the San Francisco artists displayed "tranquility in striking contrast to the skirmishes" in New York and other cities. On January 16, Col. Harold Mack, representing the regional committee, wrote to Edward Rowan, a national director of PWAP, that the first and second floors of the Tower had been sandblasted and plastered and awaited the frescoes to be executed by "twenty-six master artists and ten helpers." By the end of the month, Forbes Watson, technical director in Washington, was writing to Dr. Heil stating that he was "perfectly sure the PWAP would approve of the work going forward." Both the sketches and proposed method of organization struck him as "having as fine possibilities as any project under way in any part of the country." He ended by saying that the regional committees rather than the national office would be the final arbiters" because they "know so much more about the conditions in their regions."

Dr. Heil was pleased by the freedom of artistic expression, the promise of local autonomy, and, above all, the excitement of generating modern frescoes in the ancient tradition. Under the supervision of participating artist Victor Arnautoff, who also served as technical director or foreman, the work progressed according to plan. The government-appointed committee (Heil, Mack, Duncan, and Howe) rested assured that, as Col. Mack had said at the December 18 meeting, any work causing problems of any sort could be "whitewashed or discarded after it was done." There was a drive to accomplish as much as possible by February 15, the end of sure funding, though Bruce in Washington was hopeful of an extension to six months, at which time the Civil Works Administration was to end. Bruce wrote that the PWAP had existed as a "Federal project under a grant of funds from the Civil Works Administration" Local reporter John Barry wrote in his column in the San Francisco News that though the PWAP in Washington had been surprised that enough fresco pointers existed to "carry out plans so elaborate" as those for Coit Tower, the artists were working away in harmony. "Were there many other creative workers that could get along so well?" he asked. He credited the "dean" of the artists, Ray Boynton, who had been teaching classes in fresco painting at the School of Fine Arts (today the San Francisco Art Institute) for nearly ten years. As Heil had noted, the medium of fresco which seemed a unifying element in itself extended now to the knitting together of the designs and their execution.

The physical problems of the Tower seemed resolvable. The artists' compositions accommodated such "architectural accidents" as doorways and the "gun-slit" windows piercing the wall spaces. Lack of daylight to show Boynton's main entrance panorama could be remedied by judiciously placed artificial light. The narrow winding staircase could serve Labaudt well to show the two sides of downtown Powell Street. Some artists who had never worked in fresco before, such as sculptor Ralph Stackpole and easel painter John Langley Howard, found the new medium a challenge. Many of the artists used one another's portraits in their work since, as they said, the models were so convenient. Col. Mack, representing the regional committee, summed up the atmosphere of well-being in a compliment to the project, saying that the whole scheme was so arranged as to "produce unity." Above all, the artists sensed kindred spirits and a feeling of community among themselves.

A Disruption of Halcyon Days

But even as early as mid-February 1934 the serpent of controversy began to snake through this Garden of Eden. Its path had been laid by the destruction at the Rockefeller Center in New York of a Diego Rivera mural completed the year before. Rivera had placed a giant portrait of V. I. Lenin in that most capitalistic bastion of free enterprise. Rivera received payment for his unfinished fresco, and then his patrons suddenly destroyed the work. Among celebrities who spoke out against the destruction of the fresco, writer Lincoln Steffens said, "Capitalism could not take it. " Even "establishment" painters of national renown like John Sloan spoke of it as "premeditated art murder," although Rivera himself, back in Mexico, said he was "not surprised." The San Francisco Artists' and Writers' Union, a newly formed group with about 350 members, decided to join the nationwide protest, speaking out against this act of "outrageous vandalism and political bigotry." At a protest meeting convened in Coit Tower, muralist Maxine Albro presented a resolution, approved by the membership, regarding the destruction of the Rivera painting as, no isolated example of the prejudices of any private individual or group," but rather "an acute symptom of a growing reaction in the American culture which has threatened for years to strangle all creative effort and which is becoming increasingly menacing."

Concerned now about the spread of incidents like the obliteration of the Rivera mural, the artists cited frightening examples from Europe of growing repression and censorship in Germany, France, and Austria. More than one newspaper headline chronicling all these events appear in the paintings at Coit Tower. Even the artists' February meeting has become part of the permanent record: Vidar's newspaper in his mural notes the occasion, and in Zakheim's mural Ralph Stackpole reads a newspaper whose lead proclaims, "Local Artists Protest Destruction of Rivera's Fresco."

However, the work at Coit Tower proceeded with few problems. In Suzanne Scheur's panel called Newsgathering, her window ledge San Francisco Chronicle front page announces the end of the art project in April, though some artists continued to add finishing details until June. As the project drew to a close, San Francisco's Mayor Angelo Rossi asked that the opening of the showplace be set for July 7, 1934.

The Political Climate

External events in San Francisco in 1934 were beginning to cause tremors that were to shake the artists in their Tower. All during the spring, unemployed longshoremen and their union, the International Longshoremen's Association, were in conflict with the Waterfront Employers Association at the waterfront, just a stone's throw below Coit Tower. The union grew more militant and by May decided to call a strike that "no one, not even President Roosevelt, could stop." This Pacific Maritime Strike, extending from Seattle to San Diego and supported by other unions, created a breakdown in coastal commerce, closing the port of San Francisco. By June there was tremendous pressure from business to reopen the port, and the press added its voice to all the tumult and shouting.

The California Art Research Project of 1937 explains that "in order to arouse public opinion against the striking workers a campaign of terror and Red baiting was resorted to." As part of that campaign, the newspapers decided to make a political example of the art of Coit Tower, which as a government-funded undertaking could conceivably be called "socialistic," or in any event, pro-labor. Certain members of the press had come to view the murals and were quick to see the possibilities of fomenting a scandal for "pure sensationalism," as the artists saw it, isolating out of context several details from four frescoes on the first floor.

The Errant Artists

First, news-hungry reporters noticed that three of the four Son Francisco doilies in Victor Arnautoff's scene called City Life were depicted on the newsstand, with the glaring omission of the San Francisco Chronicle, although a space was obviously allotted for it. The Artists' and Writers' Union retorted, with some amusement, that Arnautoff attributed his omission to the prominence of the Chronicle in Zakheim's (and presumably Scheuer's) work--hence he had felt no need for further repetition. Even more galling to the local press was Arnautoff's inclusion, on another rack, of two far-left publications, The New Masses and The Daily Worker.

Next, John Langley Howard in California Industrial Life also represented the left-wing press by painting a miner reading the Western Worker, a large group of militant unemployed workers with a black man in the foreground, and "the angry faces of some gold panners glaring at some tourists" who were standing near their limousine, chauffeur and lap dog juxtaposed with a broken-down Model T Ford and a gaunt mongrel.

In his Library, Bernard Zakheim seemed to invite rebuke with more radical newspapers and especially a reader (ironically, he depicted fellow artist John Langley Howard) reaching for Das Kapital by Karl Marx; on other shelves were books written by such proletarian authors as Erskine Caldwell, Grace Lumpkin, and Maxim Gorky.

However, it was the work of Clifford Wight, a former assistant to Diego Rivera, that received the greatest censure. Wight had pointed two tall figures--a surveyor and a steelworker--on either side of a large window. Although the controversial part of his fresco is gone today, Junius Cravens, a contemporary critic, described what used to be there. Commenting on Wight's symbolizing some of the social and political problems of the time, Cravens said:

Over the central window [Wight] stretched a bridge, at the center of which is a circle containing the Blue Eagle of the NRA. Over the right-hand window he stretched a segment of chain; in the circle in this case appears the legend, "In God We Trust" -- symbolizing the American dollar, or I presume, Capitalism. Over the left-hand window he placed a section of woven cable and a circle framing a hammer, a sickle, and the legend "United Workers of the World" [sic; i.e., "Workers of the World, Unite"], in short, Communism.

In addition to Cravens's information, McKinzie adds, in 1973, the following details: Wight had labeled the three panels "Rugged Individualism," "The New Deal," and "Communism," apparently as various economic alternatives for the 1930s. Unlike all the other designs, which Dr. Heil had approved long before execution, Wight's had gone to Arnautoff directly on the job, where Arnautoff, in his capacity as project director, had approved them.

On June 2, the same day that the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce wrote a letter to the Industrial Association asking for help to open the strike-bound port, Dr. Heil had to telegraph Forbes Watson in Washington requesting guidance in what was about to become a serious controversy. He said that some artists had "at the last minute incorporated in their murals details such as newspaper headlines and certain symbols which might be interpreted as communistic propaganda." In defense of the project, he noted that the offensive elements had not been visible in the original design submission. However, although the Tower wasn't yet open to the public, "through reporters, knowledge of these things has come to the editors of influential newspapers who have warned us that they would take [a] hostile attitude towards [the] whole project unless these details be removed ." Heil asked what would happen if the artists themselves refused to make changes.

Watson answered that the murals had to be completed "according to the approved design without additions," to which Edward Bruce added that "the objectionable features [must] be removed," stating that if the offending artist refused to make alterations, others in the group should do so. Finally, he said, "propaganda of this kind is hurtful to the best interests of American art and likely to discourage further government patronage."

Complicating matters, the San Francisco Art Commission during its own preview tour of the art came to the conclusion that what it saw was "in opposition to the generally accepted tradition of native Americanism." Thereupon the Park Commission, caretaker of Pioneer Park, locked up Coit Tower, with the Art Commission dismissing the whole fracas as "typical Rivera publicity stunt." Presumably the members were thinking of the activities at Rockefeller Center.

In reaction to this new and unexpected action by city government, a group of local artists formed a vigilante committee, intending to storm the Tower and chisel the offensive portions out of the plaster. As a counter-move, the Artists' and Writers' Union threw a picket line around the Tower in order to support Wight and to prevent obliteration of the murals by either the vigilante group or the government.

In an article titled "A Frescoed Tower Clangs Shut Amid Gasps," Evelyn Seely described the chaotic scene: police had cut off the approach to the Tower halfway down Telegraph Hill, saying "someone might throw rocks, or give signals" to the waterfront below during the labor crisis, now on its way to becoming the General Strike that finally occurred on July 16.

Both the picketing and the police activities kept Coit Tower in the news during the early summer of 1934. To ensure that the news would not grow stale, one enterprising reporter for the Hearst press managed to enter the Tower, photograph the Wight hammer-and-sickle logo, and then, making a quarter-turn to his left, photograph the library scene by Zakheim. In the tranquility of his office, this reporter superimposed the logo directly above the right-hand portion of Zakheim's library mural. The doctored photo appeared with a caption reading, "Here is the painting in the Coit Memorial Tower that has caused a bitter dispute between artists and the Art Commission"; along with it was a short article correctly describing the design as placed above a large window, although the photograph obviously showed no window. The paper was later forced to print a retraction (which it buried in the back pages several weeks later), but the bad news had been syndicated in several hundred newspapers throughout the United States and Canada.

Ironically, the altered photo and the accompanying article appeared on July 5, 1934--the day San Franciscans remember as "Bloody Thursday," the most tragic moment of the waterfront strike. On that day, two union members were shot to death. Later a funeral procession of forty thousand silent men marched to the sound of muffled drumbeats up Market Street, with an honor guard of the Veterans of World War I. By agreement with the city, the workers policed their line of march; not a policeman was visible. This event was the turning point in both stepped-up strike-breaking activity and the swing of public sentiment in favor of the workers, climaxing in the General Strike eleven days later.

The Battle Extended

The Art Commission still had to decide what to do about the controversial frescoes. After much dispute, the Arnautoff, Howard, and Zakheim frescoes remained intact. However, the fate of the Wight slogans was more complicated. Wight refused to alter his painting, and no other artist seemed willing to do so. The Artists' and Writers' Union protested strongly to the PWAP on the grounds of artistic integrity. In his own defense, Clifford Wight wrote to Dr. Heil and the Art Commission that he had painted "Social Change--not industrial or agricultural or scientific development--and for this reason I made a representation of this historical fact by means of three symbols [Capitalism, The New Deal, and Communism]. " The symbol of Communism "is in no way an exhortation or propaganda, but a simple statement of an existing condition." He had been surprised, he said, at the reaction of the Art Commission to the designs above the windows, for although "no sketches were asked for," he had pinned up plans for the undertaking several days before he began to paint, with no objections from fellow artists nor from the "Art Chief," Arnautoff. In answer to Bruce's worry that Wight's action might jeopardize future governmental funding, Wight replied that he was being censored. In answer to Art Commissioner Edgar Walter's concern that the decoration appealed to only one section of the community, Wight said that the Art Commission did not object to depicting St. Francis, "who appeals to but one section of the community. The press does not attempt to conceal the facts of social change and the existence of Communism. Why should the artist be denied the freedom allowed the journalist?" he asked. Ironically, Commissioner Walter, himself a sculptor, had said quite innocently, at the December 18 meeting seven months earlier when the artists' sketches were reviewed, that a drawing such as Wight's certainly "has no surprises."

Edward Bruce responded to Wight's protest: "[The artists] are welcome to all the propaganda they want, but I don't see why they should do it on our money." He even took pains to seek legal counsel from a Mr. Harlan (possibly Supreme Court Justice Harlan Stone) regarding the eradication of the artwork. The answer was that "the effacing or destroying of the mural in question would not give rise to a cause of action in the artist. However, to attempt to alter it may possibly result in such legal liability."

History does not record nor would anyone admit who finally removed the "decoration" in question. However, when the warring sides in the waterfront dispute had come to agreement, and when the newspapers were occupied with other issues, the Coit Memorial Tower at last opened its doors to a bemused public on October 20, 1934. Junius Cravens's comments appearing during the summer airily dismissed the controversies: "There is something about fresco painting when it is applied to the walls of public buildings that seems to breed dissention. . . . There have always been naughty little boys who drew vilifications on schoolroom walls when their teachers were not looking. Likewise, there have always been mischievous little artists who put something over while they were not being watched. Of such substance is history made."

Yet on the day that Coit Tower opened, Cravens wrote with a little more humility:

A newly completed work of art is much like a fruit which still hangs, green and undeveloped, on the tree. Predictions as to its ultimate value may be made only with considerable uncertainty. Art which has survived from yesterday is still art today but more of yesterday's near-art has perished than has survived. Who can predict what of today's art will still be living tomorrow? ... San Francisco should be not only proud of [the Coit Tower] artists but grateful to them as well. And this not only for what they have given the city but also because of the courageous way in which they tackled such a Gargantuan problem, fraught as it was with difficulties and discouragements, and licked it--knocked it out cold.

Today's visitors to Coit Tower agree with Cravens's final vote of approval.

--from Coit Tower, by Masha Zakheim Jewett

POLITICS, SENSATIONALISM, AND THE MURALS

All photos of the murals were taken by Don Beatty.

Contributors to this page include:

Volcano Press - Publisher or Photographer

Zakheim, Bernard - Artist

Jewett, Masha, Zakheim - Writer

Howard, John, Langley - Artist