Literary Roots in the Long-Vanished City of God

"I was there..."

by Robert Andersen, 2025

Originally published at the author's substack under the title "San Francisco Take Two: Then, from Now"

- …the fabulous white city of San Francisco on her eleven mystic hills...

- —Jack Kerouac

1. Class of 1963

- To the memory of Michael James Monahan 16E/94'

The thick fog of a raw June day in San Francisco sixty years ago erased sightlines, so much so that the Riordan High School Class of 1963 was effectively blindsided. It never saw The Sixties coming. Rather the commencement exercise that year proved a hail and farewell to an era enveloped in a gravid gray. A Fifties valedictory. The City, The Church and The Country—the holy trinity of a Fifties boyhood—were still garbed in the raiment of fable and dogma when the two hundred graduates of the all-male Catholic high school stole away into the zero-visibility future. “Crusaders” then, we’ve worn an education in purple and gold as a cruciform relic, a memento mori, ever since.

Hence a sixtieth reunion is academic since the Class of 1963 has been observing that chasm all its alumni life. From zero to sixty in five years max. 1963 was already superannuated in 1964, the year The Sixties commenced in earnest, and by 1968 it looked positively antediluvian, six decades of change telescoped into five years, culminating in the furies of the annus horribilis. Who could remember the Vietnam of the New Frontier—Green Berets spearheading the last crusade of The Free World—or the Quo Vadis of the Vatican Council, English translation please?

Between the high noon of the American Century and the lunar darkness of the American Death Trip Telethon the ancien regime was jettisoned and a new order of time proclaimed in the streets. Even Nixon was “New.” Race, Class and Gender were hailed the new trinity, liberation theology the dogma of Sixties record. The mighty edifices once venerated had fallen like dominoes and the timeless verities committed to lifelong memory had readily surrendered to the Zeitgeist. For the Class of ’63 that Sixties gradient, a learning curve steeper than any hill in San Francisco, came as a reaping of the whirlwind to a sensibility schooled in the three I’s—the invincibility of the Country, the infallibility of the Church, and the ineffability of the City.

For the Redevelopment Agency the Youth Quake that hit the City full force in 1965, defenestrating Mr. San Francisco (Herb Caen) and sending Tony Bennett packing, was heaven sent. The Big One could proceed in tandem over the hill, out-of-sight. Indeed the paladins of the Agency could do their thing with mind-blowing license. Translating the Agency motto—“Omnes Habitare in Civitati Sancti Francisci Volunt”—into the seismic writ of the Master Plan meant the “White City”—the Mediterranean City-State favored by the frigid fogbound Pacific—was history. Rubble. A man-made Earthquake to rival the one in 1906.

Destruction of the Fillmore, early 1960s.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, aac-1901

While the saturnalia in the Haight was amping-up next door the Western Addition was being leveled without a San Francisco sound, a thousand Victorians biting the dust. Be sure to wear a hardhat over your hair. Sayonara to Harlem West. The carpet-bombing of the black Fillmore (renamed—beyond cynical—Japantown) served as precedent for the “urban renewal” that followed, as whole districts, including the waterfront, were razed to make way for the high-rise regional nexus. Good-bye to the insular City-State—Venice West—of a wide-eyed boyhood. Indeed the voluntary exodus of the Irish and Italian working class from the blue collar paradise presented the Agency with the veritable key to the Golden Gate.

No wonder the power-trip went to their heads. Psychedelia, lurid in sinuous purple, had nothing on the rectilinear lines of Gold Coast design. The Embarcadero Freeway, an hallucinogen so potent it took a major earthquake to bring it down, baldly announced the shutdown of the Port of San Francisco. By the time Dirty Harry showed up, in the early 70s, Manhattan-By-The-Bay was a fait accompli, ready for its debut as America’s Favorite City. Newly erected amusement Pier 39 housed a french-fry stand that later figured in a Barbary Coast encore.

The punk ending to Baghdad-By-The-Bay, faux shootouts on derelict piers and a City Hall bloodbath staged by a Dirty Harry manque, made the fable a real-life nightmare, call it Baghdad Noir. Though he continued to sing San Francisco’s praises Herb Caen left his heart in another City entirely. Farewell to the Caliphate of Coit Tower and the “halfway to the stars” conceit of The City Beautiful.

If The City was transformed The Church was transubstantiated. In a few years it went from being the lifeblood of the City of Saint Francis to a virtual pariah, an old wine in too new a bottle. The Faith—inflections Irish and Italian (and, in The Mission, Central American)—was all pervading in the 50s, worn on the sleeve, as the panoply of parochial school uniforms attested, and drilled deep into the psyche, as creed, conscience and rite-of-passage. The liturgical calendar was the time scheme to reckon, and thousands of hours were logged inside sacred space.

“The One True Church” was a Cold War institution par excellence, flag and cross, its holy war edge softened by a pronounced Marian strain. Holy Mother Church. It was also a consummate San Francisco institution, the civic religion, which sent you downtown in your Sunday best, easily conflating the enormous dome of City Hall with that of St. Peter’s.

To say San Francisco was Catholic is to say the Giants play baseball. San Francisco was the major leagues of Catholicism in America, so many parishes, so many religious orders, so many works of mercy—hospitals, orphanages, a necropolis even. Schools abounded in a litany of patron sainthood, not to mention the churches themselves, imposing edifices built-to-last, sublimely neo-gothic in the case of St. Paul’s, my parish, which later starred in the movie Sister Act.

For the religious orders especially San Francisco was a heaven on earth, Rome West, and a Franciscan or Dominican or Jesuit added cachet to the pulpit. The Church exerted dominion over half the populace in all matters of life-and-death, which made it totalitarian with a heart of gold—Orwell meets Huxley meets the Virgin Mary. Its authority—Sanctus Sanctus Sanctus, on display in the solemn majesty of the Latin High Mass—was from On High, its longevity proof positive that it could withstand the battering ram of history and remain impregnable.

This City of God all but disappeared in The Sixties. Its dominion vanished into the fogbelt, along with its Irish and Italian parishioners, and its authority, never so supreme as on the eve of Vatican II, could not survive the translation into plain english. Churches, once standing-room-only, became half empty and worse, while the religious orders were witness to a wholesale flight from the altar and classroom. Former Jesuits and Sisters of Mercy were suddenly everywhere in the City, released from vows or self-manumitted, doing their own thing in a new breakout idiom. The Faith had begot a New Age of spirituality—it hadn’t reckoned on reform turning into desertion en masse, a heady recusance that saw the walls come tumbling down and a new Cathedral going up, its modernist cruciform shape resembling nothing so much as a washing machine agitator.

A timely symbol as it turned out. Laundering dirty linen, spinning its image: as the legal calendar usurped the liturgical, the Archdiocese became adept at damage control. But the damage had been done long before the priesthood turned into a wanted poster. The Church had imploded in The Sixties, leaving the City Of Saint Francis, in the throes of its enforced modernization, to forge a new identity altogether. For those of us educated by the Sisters of the Blessed Virgin Mary (St. Paul’s) and by the Marianist Brothers (Riordan) the God That Failed syndrome had a pronounced matricidal theme. Holy Mother Church was now homeless in San Francisco.

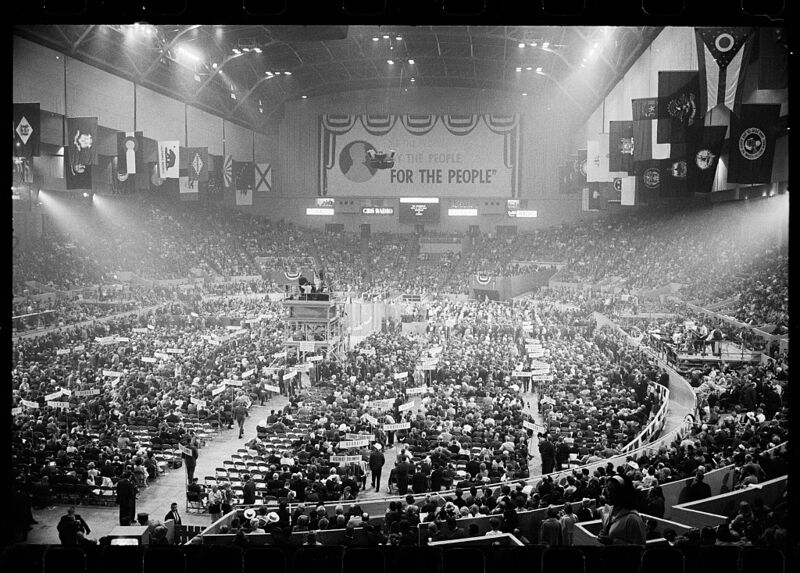

As The City and Church divorced The Country came unhinged. America Love It Or Leave It. Nowhere was the Civil War for the American Century fought with such ferocity. In fact you could say that Harper’s Ferry and Fort Sumter were reenacted in San Francisco, the City Hall HUAC “riot” of 1960 presaging the battles in the street, the Republican Convention of 1964 at the Cow Palace firing the first shots of the secessionist movement. Indeed Young Americans For Freedom was in the vanguard of grievance, stealing a march on the Berkeley Free Speech Movement. By the time Vietnam became an “out now” battle cry the Civil War had been joined on any number of fronts by the armies of the day and night.

1964 Republic National Convention at the Cow Palace, where Barry Goldwater was nominated to run against incumbent Lyndon Johnson. Johnson won in a landslide.

Photo: Warren K. Leffler, U.S. News and World Report magazine

1964 Republican National Convention in the Cow Palace brought its supporters to the Civic Center too.

Photo: pastdaily.com

The forty-nine square miles of San Francisco housed no fewer than five major military installations. Add to that the nine other significant military bases in the Bay Area and you have one of the most heavily fortified places on earth. Gold-plated duty stations like the Presidio (Army) and Treasure Island (Navy) made The City a mecca for the military. The uniform, ubiquitous then, was highly revered in Cold War San Francisco, which still basked in the afterglow of World War II. Indeed you could say that the very identity of San Francisco had been reforged in Total War. Even the birth of the United Nations at the War Memorial Opera House had a triumphal resonance. Hence the enthrallment with all things military went without saying in the Fifties.

That identity became anathema in The Sixties. Vietnam. Vietnam. Vietnam. The War came home early to the Bay Area, and its overpressure to “win” blew away the fable of Invinciblity. The Cold War shibboleths had been found out. The Free World couldn’t stand close examination, and The New Frontier looked a lot like the Old Imperialism. The “Cross-Over Point” was found here in America not “over the horizon,” as a “hot war,” waged for the hearts and minds of the American People, supplanted the “cold” cerebral one of Best And Brighest escalation dominance. Wearing the uniform in San Francisco became a fraught thing. Although the Bay littoral would become a demilitarized zone in the late 80s and early 90s—not a base left standing—this Carthaginian Peace first made itself manifest in the 60s, the psyche the place where it all went down.

In extremis was a tutelage that forced a lot of hard thinking about the comfort zone of fable and dogma. The triple deracination engineered by “The Sixties” meant the sightlines to the future were occluded by wishful thinking. What had once been gravid, the best of all boyhoods, now became grave and intractable, young adulthood reeling from one enthusiasm to the next, disabused of its laughable past. How did we ever “buy” the One True Church or The City Beautiful or The American Century? Iconoclasm suffers no fools, certainly not in the Sixties version. The battering ram of history had breached the cranium, to liberate us from our fatuity, only to deliver us to its implacable writ.

Six decades on and the auguries are not good. The City has embraced the fable of social media , bonanza economics point 49; The Church continues to be an Old Boy’s Club not quite penitential enough, exorcism required; and The Country finds itself saddled with a Leninist Party (once the Party of Lincoln) determined to bring it all down. True Believers abound, the fables and dogmas of today—centrifugal forces all—fleece the intelligence, and the reality of global warming and ecological havoc portend an ominous reckoning. Race, Class and Gender continue to slice-and-dice even as the Country plumbs new depths of inequality, welcome to Latin Americanization.

The Class of 1963 has seen it all. Twice-told as it were. The sightlines extend from one antipode to the other. The last of the “Silents” was privileged to grow up in the ur-time, when fable and dogma had real purchase, real meaning, and to come of age in The Sixties, when matriculation in the curriculum of defiance and despair meant a peremptory goodbye to all that, a radical downsizing. This education in first and last things has stood the Class well as it begins to steal away from sight for good, Michael James Monahan ’63—conscripted into that last crusade, killed in the Central Highlands in 1967—point man for the final procession.

Never mind the conventional indeed conservative cast of its chosen professions—the Class has distinguished itself in Law—a much cited Professor of Law (Imwinkelried), a Chief Justice of the Alaska Supreme Court (Carpeneti), a Federal Court Judge (Dondero)—though it has also won an Emmy (Joe Spano). By dint of sheer longevity, it has been witness to the narrative arc of two worlds—the one we have lost and the one that is increasingly untenable. Talk about improbability. In October 1962 it didn’t look like the Class of 1963 would live to see its graduation; the odds were heavily against making it to 2000 in any case. That we got out of the 20th Century alive has to reckon as a miracle capital M. In 2023 it looks now like the Class of 1963 will see it through to the last man standing. It can only hope the Archbishop (since 1990) Riordan Class of 2023, male and female (as of 2021), educated in the “Marianist Tradition” (the last religious vacated the living quarters in 2010), predominantly Asian American and Hispanic (reflective of the demographic in The City) will be so lucky. Go Crusaders indeed.

The fog lifted long ago. In retrospect The Sixties were overdetermined, too many harbingers of the Youth Quake, the Antiwar Movement, the Plateglass Revolution. The antinomian pressure had been building for some time, and Victory Culture could not “contain” so many glaring incongruities, not the least of which was the Fail Safe point. WWIII was always a half-hour away. That last crusade did not look in the least like invincibility, the semi-trance of the Latin Mass was too rote by half, and the tearing up of Market Street to make way for BART spelled the end of insularity. The endless summer of 1963 was the last hurrah of the ensorcellment, the last months of the New Frontier, the last time the fog would erase the future. The last time we would revel in pomp and circumstance.

2. A San Francisco Writer

- The tales are here. The public is here. A hundred clashing presses are hungry for you, future young story-writer of San Francisco, whoever you may be. Strike but the right note, and strike it with all your might, strike it with iron instead of velvet, and the clang of it shall go the round of the nations.

- —Frank Norris

Les Galloway and I met in the long-gone Cafe Vagabondo, on Presidio and Sacramento, in the Spring of 1973. I was twenty-seven and Les was sixty-one. Rooming in the attic of an elegant house on Clay, I was at loose ends, to put it mildly. My marriage had just gone under, and my four-year-old son was proving a reluctant visitor to his father's newfound haunts. Along with Pacific Heights, which came as something of a revelation, I had discovered the mendicant's vocation, the idyll of the vagabond writer, which meant frequenting the often-empty Cafe notebook and towhead in hand, turning spiraling thoughts into serpentine sentences.

With timeout for lusting after the weekend entertainment, the flamenco dancer on Friday night and the belly dancer on Saturday, I became fluent enough in the grandiose yearning of the writer manque to want to turn all that tortured prose to acclaim as the new prole sensation. Especially given my haut-bourgeois address. After all, I hailed from working-class San Francisco, and by way of the Navy and Berkeley had honed the Jack London pose to a psychic requirement. No genteel levitation in my future, only the Great American Lift-off would do. A latter-day Martin Eden, I was too rough about the edges to admit I knew nothing about real writing. Indeed, I was too enamored with my ambition and too beleaguered by my plight to visit the ruins of Wolf House and ponder the acrid irony of literary wish fulfillment.

Enter Les Galloway, seaman, adventurer, fisherman, writer, a Berkeley dropout who had fought in a South American war just across the border from Conrad and Marquez. London's kindred spirit in the flesh, Les moonlighted at Marina Junior High, where he taught adults the rudiments of short-story writing and lived on a steel hulled double-ender (built for Alaska waters) moored at the Marina basin. Lanky, no-nonsense, passionate about writing and women, Les cut quite an impressive figure as he took this tyro under his wing. Not a little flattered to be favored with his solicitude, I emulated his proud manner and sought—unsuccessfully—to curb my headstrong penchant for the omnibus sentence, anathema to his red pen.

Les was a master craftsman, and his limpid prose was steeped in the tradition of Crane and Hemingway. London's logorrhea wasn't in him, quite the opposite. If anything it was something of an affront to publish verbatim, when the truth lurked well below the surface, requiring the patience of the longliner. Paring down until that elemental economy emerged was the essence of real writing. Indeed, getting it right (the mood above all) separated the writer from the manque. Les had a romantic's faith that one could pull it off, which is why he never published but a few short stories, one novel (in collaboration) and one exquisite novella (The Forty Fathom Bank), his pride and joy, which he read to me one day aboard his boat, a very rare privilege indeed.

More avatar than mentor, Les loomed large that summer of my discontent. For one thing he kept me afloat, giving me work, giving me hope, giving me a rebuke when I needed one. For another we had become confidants, secret sharers as it were, and the fact that he too was reeling from love lost (a raven-haired beauty, one of his twentysomething students) made our bond all that more acute. All that more fraught with peril I should say, for Les wanted me to stay in San Francisco, wanted me to face down my demons and become a real writer. He wanted me to become the heir apparent.

But I was looking to bolt, to escape the cloister, to hit the Open Road and become an American Writer. I wanted that big lift-off, even if that meant running off to Oregon in a vain effort to will myself to escape velocity. San Francisco was a dead-end, a city borne relentlessly back to a past in the throes of being razed, to a past Les Galloway, steeped in the lore of the thirties and forties waterfront, only personified. Indeed, that derelict 70s waterfront (the apt setting for Dirty Harry shootouts) only made the Manhattanizing future that much more depressing, and if I had to be in Manhattan I wanted to be in the real one. In short I did not want to become a San Francisco writer, and that, I suspect, broke his heart.

So off I went to Eugene, where I stayed just long enough to set in motion an improbable sequence of events that delivered the manque into the Big Time. I never saw Les again. Two years later, just shy of thirty, I found myself in Gotham, writer’s heaven, at Elaine's, ensconced at The Table reserved for literary celebrity. A very famous editor asked me to do a book, and the heady conversation with the likes of Garry Wills and Carl Bernstein (Nora Ephron alongside, then all eyes for Carl) only vindicated my Go East Young Man trajectory. The Big Lift-Off had materialized, or so I rashly presumed, intoxicated with my wish fulfillment. I was an American Writer now, and that meant adopting a patronizing attitude toward the Left Coast. Like fellow Native Son and Elaine’s regular Lewis Lapham I wrote off a San Francisco mired in lifestyle provinciality. Poor Les, stuck on a boat in the Marina, endlessly revising his novella. Thank God I had resisted his entreaties, had not heeded the siren-song that is San Francisco.

Now the verdigrised one, fast forward too fast, I find myself staring Wolf House down, any number of acrid ironies attending my topsy-turvy career. For lo and behold I find myself being borne back to the past, in the haunting fashion that Les describes in his Conradian tale of secret sharing. Like the down and out protagonist of The Forty Fathom Bank I too wanted it all, which meant wishing to disappear from the mentor who first made all the difference.

I can still see Les hunched over the manuscript, intently reading his eerie account of a shark hunting windfall turned sharkish. The story is rife with foreshadowing, the “willed” sundering of an inescapable bond. One minute Les loomed larger than life, the next he was gone, just like the stolid, knowing fisherman in the novella. The devouring of our bond caught me unawares, unaware of just how much that time aboard his boat figured in my subsequent literary careering. Too long hugging the shore (in Updike’s telling phrase), reviewing the books of others, that Forty Fathom Bank represents the demarcation line that separates the writer from his manque.

Irony of ironies then, this "Maine" writer (SF Chronicle) is now looking to assume the mantle of San Francisco writer. To return to his Native Ground after all these years in exile, to make peace with the ghost of Galloway and jump the queue come what may. Gangway. Which is to say to pick up where Les left off (he died in 1990; The Forty Fathom Bank was published by Chronicle Books in 1994) and attend to that longline, that tradition of San Francisco writing that extends all the way back to Norris and Bierce, Twain and Dana.

A tradition of American Writing, I might add, for in the Republic of Letters the San Francisco writer has always held dual citizenship. Lived aboard that double-ender as it were. The San Francisco of 2022 is a far cry from Café Vagabondo days but the cityscape of the literary imagination remains what it always has been, a place imbued with the spirit of a Les Galloway. A place of high adventure. Just this side of fratricide. To survive in the sharkish world of high tech San Francisco takes guts and guile. Craft. Social media translates gutturally into Social Darwinism. SoDar. The Rebarbative Coast. Watch your back.

In the Fun House at Playland-At-The-Beach there was a Joy Wheel, which spun you off into the padded sidewall once it came up to speed. While Laughin’ Sal would side-split ad nauseum we kids would jockey for position, dead center the hotly contested perch. Push come to shove. Think of San Francisco as a Fun House, where twentysomethings flaunt having it all, waited on hand and foot by their spiteful contemporaries, where the Joy Wheel spins without letup and Sal guffaws at your holding-on-for-dear-life plight. No padding. Of course dead center is where everyone wants to be. Everyone wants to live in the City of St. Francis proclaims the Latin motto of the Redevelopment Agency. Everyone that is except the San Francisco Writer. It’s enough to room in an attic on Clay before centrifugal force sends you packing. The SF writer is nothing if not far-flung. Restive. None of the eminent ones stayed put.

Sooner or later though you will exercise the right of return. To finally haul in that long line dealt out all those years ago. Les was right. Patience is all. Now that the twentysomething has become the sixty something, his San Francisco long gone, it becomes imperative to get it right, mood above all. The omnibus sentence, never mind the urgent ambition, has yielded to the pith of knowing when to begin anew, this time in fiction. Wised-up. Elemental economy 101.

That Spring of 1973, giddy with my newfound warrant, I dropped a longline atop Parnassus. The UCSF MedCenter is where I thought to make my name as a San Francisco writer. Lugging a backpack-sized tape recorder I dubbed Diogenes Lantern, I made a nuisance of myself in quite a few labs, asking some very leading questions about the nature and purpose of the work. “Fascinating”—or, as often as not—“Get him out of here.” It was, it turned out, my eureka moment. My ticket to the East Coast. Now that the Forty Fathom Bank has moved to the forbidding expanse of Mission Bay, I can, as Les taught me, painstakingly haul in the catch. At long last. Even though my novel-in-progress City of the Sun is set on the Torrey Pines Mesa of La Jolla, subtitle A Novel of the New California, it is very much a San Francisco book, not least an homage to Les Galloway and Frank Norris.

You were either on the bus or off it following the Summer Of Love. It’s a far cry from the Monday Night Class (held next door to Playland at the Beach) to the faux class warfare surrounding the Google bus, but passing the time reading the send-up of Dave Eggers brings the saga of this San Francisco writer full circle.

The City Of Memory and the City Of Destiny face-off in very small quarters. Too intimate by half. The seismic writ of San Francisco is as much above ground as below. First the Argonauts, then the Hippies, now the Geeks. Will San Francisco weather this Youth Quake. Or is this it, Apocalypto, the Great Fire Sale. Selling-out and cashing-in enfant terrible fashion is a surefire formula for permanent burn-out. App-Hap. Good luck with the rest of their lives. A new generation of bums haunting Market Street. State-of-the-art.

Already the Digital Divide investing of San Francisco is superannuated. Tech Disrupt indeed. Unbeknownst to the techies surging into the Moscone Center for their Summer of Love the Zeitgeist has moved on, crossed that Forty Fathom Bank into terra incognita. Very deep water indeed. Monday Night Class at playland by the bay. Who knows what sleek beast will issue from the new biotech campus at Mission Bay. While opprobrium is fixated on Market Street, who’s on the uber bus and who’s not, the big story of San Francisco going forward—the place where Memory and Destiny beget the Next Big Thing, perhaps the Biggest of them all, Gold Rush included—goes unheralded. Beneath the radar. SoSoMa with a vengeance.

Venture past the Ballpark and find yourself on streets only a Frank Norris would recognize as worth their weight in literary gold. A dentist on Polk Street and now a scientist on 4th and 16th. Eureka. It’s all there awaiting the next Dave Eggers (The Circle: Destiny) or Karen Yamashita (I Hotel: Memory). The San Francisco writer shuttles between the two Cities with abandon, because both in extremis, ever mindful that today’s windfall is tomorrow’s whirlwind. The lesson, talk about acrid, talk about irony, of Wolf House. Dead center indeed.