Quigleys of Golden Gate Park

Historical Essay

by Angus Macfarlane

This article appeared in The Argonaut: Journal of the San Francisco Historical Society, 35, No. 1 (Summer 2024). Reprinted with permission.

Lone Mountain Cemetery, 1866, looking west. Running along left side is Point Lobos Toll Road (Geary Blvd. today). Lone Mountain at immediate left.

Image: courtesy David Rumsey

San Francisco Examiner, November 16, 1912

Two men are mythologically synonymous with Golden Gate Park: William Hammond Hall, often called “The Father of Golden Gate Park,” and “Uncle John” McLaren, park superintendent for fifty-three years. Miracles have been attributed to these men, often proclaimed to be geniuses and visionaries, but visions do not become reality without hard work.

Perhaps the hardest worker in bringing the dream of Golden Gate Park to life was a park laborer whose forty-year career from 1872 to 1912 connects the tenure of Hall and McLaren: Patrick Quigley. Patrick is totally unknown, undocumented in Golden Gate Park history; yet his spirit permeates Golden Gate Park, his life’s work still surrounds us, and we all owe him a debt of gratitude when we go to the park seeking relaxation, recreation, and rejuvenation.

But it’s not just Patrick’s story. It’s also the story of his family and their contributions to Golden Gate Park.

The Original Miracle Worker

On April 4, 1870, California Governor Henry Haight signed An Act to Provide for the Improvement of Public Parks in the City of San Francisco, thereby creating Golden Gate Park, The Avenue (today’s Panhandle), and Buena Vista Park. These parks were to be administered by a governor-appointed, three-member park commission, which was authorized to issue bonds to raise money for the improvement of the parks. The new commission held its first meeting on May 3, 1870, when the park’s first employee was appointed: Commission Secretary Andrew Mulder at $75 per month.(1) At the meeting on July 5, 1870, $15,000 in park bonds were sold.(2)

Now, with money in hand, the task of building a park could begin. But San Francisco, a young city of 150,000 people, had no experience in park building because it had no parks.

San Francisco inherited its first “park,” Portsmouth Square (when it was simply known as “the Plaza”), from the Mexican pueblo of Yerba Buena. Being the only centrally located open space in the little cove-side settlement, the 1.5-acre Plaza became a “public park” in the 1840s.

San Francisco’s attempts to make Portsmouth Square its central park were spectacular failures. The newspaper offices of the Daily Alta California (Alta) overlooked the square and gleefully documented the feeble attempts at park-making:

The Plaza: Useful and Ornamental For years the Plaza has been a shame and a disgrace to the city—a natural reservoir of dead cats, cellar filth, sole-less boots, seat-less breeches, broken crockery—the city’s sink and cesspool, growing uglier by daily accretions of garbage, fetid and stenchy. If the City Council have any taste, any pride, any love for their fellow citizens, any interest in the beauty and health of the city for which they legislate, let them at once do something to reclaim this land-blot, worse than an Irish bog, this unsightly city sore. The subject has been discussed. Attempts have been made to improve it. They have all and each only made it worse. … It disfigures the earth, disgraces the city, infests the air, disgusts the sight, shocks all taste and is ugly enough in its deformity to make piety profane.(3)

Masonic Cemetery circa 1873, looking south from Lone Mountain. Road in foreground is today’s Turk Street. Line of trees in the background is the newly planted Golden Gate Park Panhandle.

Image: courtesy of the Bancroft Library, 1963.002:0568-F

Six months after the Alta’s unflattering portrait of our city center, Mayor C. K. Garrison, in his message to the common council, said:

I would urge upon your honorable body the importance of some plan being adopted for the improvement of the public Plaza ... in such a manner as will render it an agreeable promenade for our citizens, instead of remaining as it now is and had long been, a public nuisance and a public disgrace.(4)

The book The Annals of San Francisco pontificated:

Not only is there no public park or garden, but there is not even a circus, oval, open terrace, broad avenue or any ornamental line of street or building, or verdant space of any kind, other than the three or four small squares alluded to; and which every resident knows are by no means verdant, except in patches where stagnant water collects and ditch weeds grow.(5)

While San Francisco staggered and stumbled toward making the Plaza a civic ornament for the living, the dead were straining the capacity of the city’s seventeen-acre Yerba Buena Cemetery at Market, Larkin, and McAllister Streets, the cemetery that was supposed to accommodate the city’s deceased for “the next half century.”

A week after the mayor’s message, the Alta reported that 320 acres (one-half square mile) had been bought for a cemetery about three miles west of the Plaza. The land was described as “undulating and covered with oaks and shrubbery near the hill known as Lone Mountain.”(6)

At this time back East, the “garden cemetery movement” had begun. As the name implies, cemeteries had become landscaped gardens for the final resting places of the dearly departed, as well as attractive places for the living to enjoy nature instead of gloomy and foreboding “cities of the dead.” Lone Mountain Cemetery would be San Francisco’s first “garden cemetery.”

The Alta, which had ridiculed the city’s Plaza, praised the beauty of the emerging garden cemetery as “Worthy of our great and growing city. … One of the most pleasant rides in the vicinity of San Francisco is over the grounds of the Lone Mountain Cemetery.”(7) Many years later, the San Francisco Examiner described it as having “about 20 miles of walks, lanes, paths, and avenues … which abounded with never-resting humming birds, myriads of butterflies, and lines of marching quail.”(8)

In 1860 the Catholic Archdiocese bought sixty acres of the Lone Mountain tract for a Catholic cemetery—Calvary. The improvements at Calvary Cemetery included:

ten miles of walks and drives skillfully and tastefully exhibited in the landscape gardening. The tract is laid out in beautiful designs, the avenues and walks traverse each other in regular circles, curves and ellipticals. Care has been taken to preserve the natural features of the location. The cemetery commands one of the finest views in our neighborhood.(9)

As more and more of San Francisco’s wealthy pioneers were buried in these garden cemeteries, magnificent monuments were erected in their memories and as reminders of their wealth and power in life. Soon these cemeteries, with lush landscaping, grandiose memorials, fountains, and panoramic views, became weekend destinations for the living. Relatives of the deceased and simple citizens, seeking to escape the city’s unhealthy environment, mingled among the graves and along the paths. With no public parks worthy of the name, these cemeteries became San Francisco’s de facto public parks.

In 1864 the Order of Freemasons bought thirty acres on the site of today’s University of San Francisco campus for the Masonic Cemetery. The site was described as:

... one of the most eligibly located of our suburban resting places; a location which for picturesqueness is unsurpassed by any tract of land on this peninsula. The cemetery is sup- plied with water from an artesian well. There is a central fountain on the grounds which enhances the almost romantic beauty of the abode of the dead.(10)

Heavy machinery at work in Golden Gate Park. Photographed by Isaiah West Taber, from the Marilyn Blaisdell collection.

Photo: OpenSFhistory/wnp37.03163

At the same time, San Franciscans struggled to get a breath of fresh air untainted with:

... fumes from decaying animals and vegetable matter, the horrible stench from ill-construct- ed drains or cesspools and the dust and dirt which is whirled about by the bushel on every breeze which sweeps over the thickly settled portions of the city.(11)

In 1866 San Francisco prevailed in its years-long lawsuit against the United States over ownership of the Outside Lands, growing by 17,776 acres or 27 square miles.(12) The city intended to create “a public park of not less than 1,000 acres” in the new lands.(13) Now the dream of a real public park could be realized. Soon the dead could rest in peace, and cemetery visitors would finally have a real park—a park for the living—to enjoy.

With money in hand from the sale of park bonds, the park commission’s first order of business was to survey the park. As the lowest bidder, William Hammond Hall won the contract. He began his work in August 1870 and was finished by February 1871. In the meantime, Patrick Owens was appointed keeper of the park (employee number two) on November 17, 1870, at $75 per month.(14) His job was to protect trees and shrubs from trespassers. Forgotten in history is that the greatest threat to the early park was cows. Nearby dairies let their cows roam free to forage on the thin vegetation. The new plantings in the park were more tempting than the poor vegetation that grew in the area.(15) A later responsibility of the keeper was to watch over the nursery and greenhouse. In addition to his salary, Owens was provided a residence in the park near today’s Stanyan and Oak Streets.(16) The southern boundary of Masonic Cemetery was today’s Fulton Street. Beginning in August 1870, visitors to the cemetery could witness history being made a few hundred yards downhill in the unsettled and undeveloped “Flyshacker Valley.”(17) This activity would have been William Hammond Hall’s survey party laying out the boundaries of San Francisco’s new public park.

Hall’s surveying was finished by February 1871; by May, work had begun on leveling the thirty-acre Avenue—today’s Panhandle.

The dream was now leaping off the drawing board onto the real world. Today the Avenue/Panhandle has the appearance of a thirty-acre billiard table: a perfectly flat and level surface. Before that perfection could be achieved, however, hills had to be flattened and hollows filled. Ultimately, 273,000 cubic yards of sand were redistributed—enough to bury a standard 240-feet-by-600-feet Sunset District block, fifty-one feet deep in sand.(18) This was during the time when manual labor technology was the same as it had been four thousand years earlier when the pyramids were built: man- and beast-power. Sweaty, sore-muscled men with blistered and calloused hands wielded simple hand tools. The era of steam power was just beginning, with the famous “steam paddy” or steam shovel used for large excavations, such as the leveling of the Avenue.

During this year-long project, Masonic Cemetery visitors could see and hear more than one hundred men working in Flyshacker Valley, likely including Patrick Quigley, a forty-two-year-old, marginalized “Irish need not apply” American immigrant with eight mouths to feed.

While this project was underway, William Hammond Hall was appointed superintendent(19) of the park on August 14, 1871(20) at $250 per month, making him park employee number three.

After the Avenue was leveled came the macadamizing, or surfacing, of the seventy-foot-wide road that meandered through The Avenue from Baker to Stanyan Street—the grand entrance to Golden Gate Park proper.

Park payroll for May 1872 has the first reference to Patrick Quigley. From the park commission meeting minutes, June 6, 1872, page 33.

Courtesy of the San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

From September 1871 to March 1872, work was proceeding above and below the park surface: The Avenue was macadamized; a redwood sewer was connected from the park to the city’s sewage system; a three-mile-long service road was being pushed through the sand to the ocean; a metal, gated fence was erected around The Avenue; and a wooden fence was put up around 280 acres of “arable land” east of Stanyan Street—more protection against the marauding cows. The remaining seven hundred acres stretching to the ocean was a forbidding waste of yet-to-be subdued drifting sand.

On March 20, 1872, the San Francisco Examiner reported that 115 men were at work in the park planting trees and grading roads. The careful reader might ask: how could the park have only three employees (Secretary Mulder, Keeper Owens, and Superintendent Hall), while 115 men were at work? The answer is that there were three classes of park “workers.” One class of worker was the men who were employed by and paid by the contractors who had won bids from the commission. These were “contract employees,” not park employees. Another class was the temporary/as-needed day laborers who were briefly hired for a specific project or task. These men were referred to as “dollar-a-day men” for the wages they earned. Again, they were not park employees. The final class of park workers was the appointees. These three men—Secretary Mulder, Keeper Owens, and Superintendent Hall—were formally appointed to their positions as park employees by the park commission with a fixed monthly salary.(21)

The park’s May 1872 payroll reflected growth and staffing changes. By then, conditions had reached the point that planting could begin, so a chief gardener and a foreman gardener were appointed, the park’s fourth and fifth employees. William Bond Pritchard’s appointment as general foreman—Hall’s second-in-command at $125 per month—is recorded in the May payroll (employee number six).(22) The keeper’s previous dual responsibility of preventing trespassing and guarding the nursery and greenhouse was bifurcated. A new keeper (the seventh employee) was hired to watch for trespassers, while Patrick Owens became the new nurseryman in charge of the greenhouse and nursery.(23)

Appearing for the first time on the official park commission May payroll roster was Patrick Quigley, designated “foreman” at $80 per month, Golden Gate Park’s eighth employee—and the first laborer.

Our Golden Gate Park is a world-famous, man-made miracle. Being the first laborer officially appointed by the park commission, Patrick was the original miracle worker. It would be his lifelong task to transform this unadorned, sandy wasteland into San Francisco’s beauty spot. He would devote the rest of his life to watching over and protecting the nascent park from conception to maturity, as a godfather would.

Formal hiring document signed by William Hammond Hall, October 25, 1872.

Courtesy of Susanne Burzinski (née Guedet).

Meet The Quigleys

There is no record of how Patrick Quigley, a forty-three-year-old retired Irish-American grocer with eight dependents,(24) came to Superintendent Hall’s attention. More than likely, he rose from the ranks of either the contract employees or the dollar-a-day men. Another possibility is that, as mentioned in his obituary, he distinguished himself to Hall during the shotgun battles to evict the squatters from Buena Vista Park in early 1871. In any case, to be a “foreman” required having exceptional job skills and the ability to lead and direct workers effectively. With more than one hundred men on the job at a time, competent leadership was essential.

Whatever Patrick’s origins in the park’s labor force, he obviously stood out. His $80 paycheck was the first of nearly five hundred monthly paychecks that he would receive during his forty-year park service career before dying on the job at the age of eighty-three in 1912.

When Patrick began his career, the park was in its embryonic stage, having shape (its boundaries established in the Outside Lands survey of 1868)(25) but lacking substance. Only the eastern/Panhandle portion had soil fertile enough for immediate plant- ing. Thus, the park grew from east to west, while reclamation of the sand desert was from west to east. Little is known of Patrick Quigley’s early years. He was born in County Roscommon, Ireland, on March 14, 1829. He arrived in the United States in 1848, one of the tens of thousands of refugees fleeing the Irish famine.(26) In the early 1850s he crossed the plains from St. Louis to the Mariposa gold country where he was a miner until work in business attracted him. For most of the 1850s and 1860s, he operated the popular Oak Springs House in Mariposa County.(27)

In 1858 or 1859 he married Mary Donovan, nine years his junior, also from County Roscommon.(28) It is not known if the pair knew each other in Ireland or when or where they were married. The first hard evidence Patrick left in the public record is in the 1860 U.S. census, which lists him living in San Francisco as a drayman (a delivery wagon driver), living with his wife, Mary, and their three-month-old son, James.

The Quigleys returned to Mariposa County and the Oak Springs House where, over the next nine years, five more children would be born. Additionally, Patrick became a naturalized American citizen in Mariposa in 1864.

Patrick Quigley in Golden Gate Park, November 6, 1912.

Photo: courtesy of Susanne Burzinski (née Guedet).

The 1870 census finds Patrick and Mary back in San Francisco with six children. Patrick is now listed as a retired grocer. The 1871 city directory lists Patrick as a laborer, consistent for someone working in Golden Gate Park.

Because of his importance to the new park and the distance from town to the work site, Patrick and his family (by now including seven children) merited a home in the park so he could be close to his responsibilities and available at all times.(29) It would be ten years before even the park superintendent had a home in the park.

The exact details of how the move to Golden Gate Park came about is a missing piece in the family’s history. As noted above, a park residence was built for the keeper and a budget item for its construction is in the park’s records, but there is no mention of a residence built for the Quigleys.

The house given to Patrick Quigley in Golden Gate Park by the park commission, 1912.

Photo: courtesy of Susanne Burzinski (née Guedet).

A possible scenario: In 1865, before Golden Gate Park was even conceived, a state-chartered, privately-operated toll road ran from Fulton and Divisadero Streets roughly southwest to Lake Merced: the Central Ocean Macadamized Toll Road, also called the Powder House Road, or the Central Road. When Golden Gate Park was laid out, the southeast corner overlapped a half-mile segment of the road from today’s Stanyan and Fell Streets to Kezar Drive, Lincoln Way, and Fourth Avenue. Being a state-chartered entity, the road was there to stay. The park commission could not seize the road through eminent domain.

Apparently, before the park was laid out, someone built a house adjacent to the road on what would become park property. The park commission could and did seize the structure and gave it to the Quigleys. A man named Thomas Finnigan tried at least twice to sell it to the park commission for $550.(30) He was unsuccessful each time.

The Quigley home in Golden Gate Park, 1911 in upper left corner. Polytechnic High School is under construction,lower lefthand corner, foreground.

Photo: courtesy of The Perennial Parrot (Polytechnic High School Alumni Association)

The Quigley home for the next forty years was located on the two-acre triangle of land west of Kezar Stadium bounded by Kezar Drive, Lincoln Way, and the extension of Arguello Boulevard into the park. This free home was not a bed of roses. Patrick and Mary moved into the house with their seven children: James, born 1860; Charles, born 1862; John, 1863; Thomas, 1864; Elizabeth, 1865; Mary, 1867; and George, 1870. Five Quigleys would take their first breaths in their Golden Gate Park home: Bridget in 1873, Katy in 1875, Francis in 1877, Joseph in 1880, and Patrick, Jr. in 1883. Eight Quigleys would exhale their last breaths in the park: Katy, Francis, and Patrick Jr. in early infancy, as well as Charles, Joseph, Mary, Patrick, and John in later life. The Quigleys were literally and figuratively Golden Gate Park’s First Family. They were also true San Francisco pioneers—some might say exiles—daily confronting the hardships and challenges of isolation, sand, wind, abysmal weather, and fog miles beyond the western limit of settlement. By necessity, they were self-sufficient with a vegetable garden and livestock, likely milk cows and chickens, and probably pigs, lambs, and goats. Their city-provided home lacked indoor plumbing. Their water came from a well until they tapped into the Spring Valley Water irrigation line to the park. Warmth came from a wood-burning stove, and candles and lanterns provided illumination. A fence encircled part of their homestead to keep farm animals and younger children from wandering off.

In all likelihood, Patrick was provided a nineteenth-century equivalent to an SUV or truck: a horse and buggy for work use and for forays into the distant city for needs and necessities. Their nearest neighbor was the California Powder Works (a dynamite factory) and its employees, 250 yards to the south at today’s Second Avenue and Irving Street, within sight and sound of their home. Patrick Owens, the keeper of the park, lived half a mile to the northeast. The Alms House (today’s Laguna Honda Hospital) with its three hundred or so “inmates” and staff was one mile to the south. Another dynamite factory, the Giant Powder Works, was one mile to the southwest. Cornelius Reynolds’ hog farm was two-thirds of a mile west at today’s 14th Avenue and Lincoln Way.

A constant hardship for the Quigleys was the wind that blew unabated from the ocean, rearranging the sandscape. Nearby Laguna Honda School found the sand around its foundation being eroded away, destabilizing the building.(31)

But the wind carried something even more troublesome than just sand. The Quigleys lived downwind from Reynolds’ hog farm. The prevailing westerly winds delivering the noxious by-products of his stock must have been sickening. Probably so sickening that within two years of the Quigleys’ arrival, Reynolds was a park employee, and the hogs were gone.

At first, the Central Road was the Quigleys’ only link to civilization to the east. Occasional saloons dotted the road, providing liquid refreshment and courage to the teamsters delivering raw materials to the dynamite factories and returning with volatile finished products. This happened just mere yards from the Quigley home.

Throughout the 1870s, the Quigley kids passed the dynamite factory on their quarter-mile journey along the Central Road to Laguna Honda School, a two-room building on today’s Seventh Avenue near Irving Street. This educational outpost served the few families south of the Presidio, west of Masonic Avenue, east of the ocean, and north of Sloat Boulevard—thirteen square miles, or one-fourth of San Francisco’s total area.

Early park workers were divided into construction, maintenance, and horticulture.(32) Every park’s public face is the flora. Thus, the gardeners are credited with being the creators of the park. Flora is merely the park’s “skin.” Beneath the skin are the skeleton and muscles: the infrastructure that few see or appreciate but that supports the skin and even makes it possible. The labor of creating access to the planting sites for both gardeners and the public, as well as to site preparation, was taken for granted. Patrick and his workers had little to do with the park’s horticultural aspect, but they made the horticultural part possible.

Park employees were also Park Police Officers (at no extra compensation) with the authority to arrest and detain park rule violators. They were required to provide themselves with a badge at no compensation.(33)

Until the eight-hour-workday law took effect in 1900, park employees worked nine full hours of “faithful and efficient labor” six days a week, plus one Sunday a month.(34) A large, centrally located bell tolled the start and end of the workday.(35) The park’s initial funding came from the sale of park bonds. After the bonds were sold, the park was dependent on uncertain, late, and inconsistent tax levies to survive, frequently resulting in staffing cuts and project delays.

After two years on the job, Patrick’s work ethic and leadership skills were recognized and rewarded with a pay raise and this high praise from Superintendent Hall:

The foreman teamster now receives $80 per month. I recommend that his pay be increased to $90 per month. The duties and responsibilities of the office require a good man to fill it and the past conduct of the present employee—P. Quigley, the oldest employee on the force—shows him to be worthy of the position and deserving of the salary.(36)

During his forty-year career, Patrick had many job titles: teamster foreman, labor foreman, construction foreman, foreman of the roads, superintendent of the roads. Legitimately, Patrick’s years of experience and depth of knowledge gave him valuable insight and input on every infrastructure project in the park’s early years.

As foreman, Patrick was the equivalent of a top sergeant in the army, responsible for varying numbers of workers. He would not have had policy-making authority, but he would have been an in-the-field decision maker responsible for carrying out orders from above and delegating, overseeing, and even doing the work of building, maintaining, and improving the new park. From Hall’s praise we can infer that Patrick was a valued and trusted subordinate.

Looking east at Golden Gate Park, 1876 “under construction.” Cemeteries at upper left.

Source: Library of Congress

Park Affairs

In 1876 the serpent of politics slithered into our Garden of Eden. Like weeds and gophers, once politics became established in the park, it was impossible to eradicate.(37)

According to author Raymond Clary, Superintendent Hall fired a blacksmith named Sullivan for padding his bill. Sullivan swore revenge on Hall, and when he became a state assemblyman Sullivan began a vindictive, muckraking investigation into Hall and his park administration. Although no fault was found with his leadership, Hall resigned in disgust in January 1876.(38)

The eleven years following Hall’s resignation were difficult times for the park. The next two superintendents were capable and conscientious men who found themselves having to do more and more with less and less. W. B. Prichard, Hall’s subordinate for four years, endured five years of politics, patronage, false economies, egotism, political indifference, and interference in park affairs by City Hall. He resigned on March 1, 1881. F. P. Hennessey was the next superintendent, elected on May 9, 1881. He had thirty-five years of experience and study in engineering, rural architecture, and landscape gardening, which qualified him to head the park but did not prepare him to deal with San Francisco’s politicians who did not share his interest in the park’s welfare.

Chaos was brewing as funding wasn’t keeping up with bills. The head gardener resigned when ordered to do more. Seventeen laborers were released, and more were being considered for termination. The police force was discharged. Park funding, always a problem, reached a low point in December 1881 when park tools and assets were auctioned off. A gray mare named “Maud” fetched $70; two mules, “Nelly” and “Seal,” brought in $197.50 total; 410 shovels and 76 picks raised $8 and $7.50 respectively. The auction raised $770.64, not enough to close the deficit.(39)

In a “cost-cutting move,” Superintendent Hennessey was fired on July 1, 1882, and replaced with John J. McEwen at half his salary. According to Hennessey, McEwen admitted to having no experience for the job.(40) At a subsequent park commission meeting, the park force was eviscerated. The Chronicle reported that Commissioner Pixley suggested that Patrick Quigley be fired “since no construction force existed.” Commissioner Alvord pointed out that someone should be on hand “to keep the roads in repair,” to which Commissioner Rosenfeld suggested that Quigley be kept on at a salary of $2.50 per day instead of his current $3 per day.(41) In the end, the park commission discharged all employees not performing physical labor.(42)

After ten years on the job, this was Patrick’s career high and low points. He was deemed vital enough to survive the employee purge but was left with no staff to assist with the work. Park attendance was growing, from 546,833 in fiscal year 1874–75 to 1,608,911 the year before the purge (1880–81), dipping to 729,202 the year of the purge (1881–82).(43)

In 1881 park commissioner William Alvord donated $200 for [[Alvord Lake |a lily pond near the Haight Street entrance]]. It was just a shallow basin, but it was the first man-made lake in the park.(44) However, it was not the park’s only body of water. Maps and surveys from the late 1860s to 1890 show several park features labeled Lake. The largest encompassed what would become the North and Middle Lakes of the Chain of Lakes in 1900. Another large body of water covered today’s Arboretum. A lake four to five acres in extent covered the field east of the children’s playground. A three-acre lake could be found behind today’s maintenance yard. These were vernal pools or vernal ponds: shallow, sometimes seasonal, sometimes semi-permanent bodies of collected rainfall or from a water table near the surface.(45) No doubt, Patrick and his decimated wheelbarrow battalion had a hand (or a shovel or two) in the creation of Alvord Lake and the filling in of the unnamed vernal ponds.

Mary Quigley: Golden Gate Park’s Pioneer Mother

Fifty yards from JFK Drive on Stow Lake Drive is the Pioneer Mother Monument, installed in 1940. This monument could be, in fact should be, in honor of Mary Quigley, Golden Gate Park’s true pioneer mother. While Patrick toiled six days a week, nine hours a day, alongside his co-workers to create and maintain our urban treasure, Mary toiled seven days a week, mostly by herself, to raise a large family and maintain a home under the most difficult and trying of circumstances in San Francisco. She had no support for raising her seven children with a ten-year age range—later ten children with a twenty-three-year age span. While some of the pressure was relieved by the older ones attending school and helping at home, Mary still had the young ones who needed constant attention.

Patrick’s contribution to Golden Gate Park was physical. Mary’s sacrifice to Golden Gate Park was emotional and psychological.

The first few years in Golden Gate Park must have been unbearably stressful for Mary. Another missing piece of the Quigley puzzle is exactly when they moved into their Little House in the Park. If it was in May 1872, the month that Patrick received his first paycheck (or perhaps earlier), the family received a rude welcoming on Friday, June 21, 1872, when “a strong shock, followed by a thunderous clap, rattled the windows of every house in the city.” At the California Powder Works, 250 yards from the Quigley home, 1,500 pounds of nitroglycerin exploded, “tearing to atoms” six wood-frame buildings on the factory site, leaving a crater in the sand twelve feet deep and fifty feet in diameter. One newspaper account described the site as “a waste—a deserted wood yard with only the chips left.”

San Francisco Chronicle, June 22, 1872

Many residents in “distant” San Francisco thought it was an earthquake. People living nearby were thrown prostrate to the ground, and some houses nearby were shattered into almost unrecognizable shapes. The shock was felt by ships five to eight miles at sea and a “flash that looked to be thousands of feet high” was seen.(46)

Mary would have had no warning. A blinding flash of light would be followed a micro-second later by the supersonic shock wave, ending with the deafening sound of the blast, all in a fraction of a second.

Six months later, it was “thar she blows” again. Mary was five months pregnant with Bridget when 300 pounds of nitroglycerin erupted on December 21, 1872. The powder works explosion was heard miles away. A 190-by-60-foot wood frame building on the site completely vanished, while pieces of it were found up to a mile away. Employee body parts were found up to six hundred feet from the blast site. Witnesses on the Point Lobos Toll Road (Geary Blvd.) two miles away saw the roof of a shed sail more than two hundred feet into the air. The newly opened Laguna Honda School, about a quarter mile from the disaster scene, suffered broken windows and cracked plaster. Thankfully, the school was closed for the Christmas holiday. The powder magazine, two hundred yards from the blast site, contained 10,000 pounds of powder but was undamaged.(47)

The third explosion was on June 8, 1877. Witnesses reported seeing “an immense lurid flame of the grandest description shoot into the air followed by a bright cloud of dense yellow smoke.” The building in which 500 pounds of nitroglycerin had ignited no longer existed. The hillock on which the building once stood had been transformed into a hollow.

The doors, windows, and side facing the blast were torn off the plant foreman’s house, 150 yards away. (Note: The Quigley home was 250 yards away.) Not a single piece of wood larger than a splinter could be found. Windows a mile away were broken. The White House Saloon, operated by William White, three hundred yards from the powder works, was completely wrecked. The adjoining Park Saloon, run by Charles Kuhirt, was also damaged with the occupants cut by flying glass. John B. Williams’ Oak Leaf saloon at Seventh Avenue and H Street (Lincoln Way) was completely wrecked.(48)

Strangely, there was never a mention of the Quigley home, a mere 250 yards from ground zero of these foundation-shifting disasters. Reports of the blast-damage radius were much greater than the distance between the blast site and the Quigley home with nothing in between to mitigate the force of the explosions. Was the Quigley home damaged or destroyed each time, yet repaired and improved each time without any news reports? We can only speculate. If so, this was indeed a silver lining, since the original structure would have been rather small for such a large family.

The only references to any work done on the Quigley home were repairs to the tin roof over the kitchen, sheathing on the stairway, and plastering the upper part of the house in fiscal year 1881–82.49 On September 1, 1877, three months after the third explosion, the Examiner published the following:

San Francisco Examiner, November 1, 1877.

Maybe after five years of social isolation; constant terror about when the next explosion would happen and the damage and injuries that could result; two years of intolerable hog stench; the bad weather in San Francisco; three pregnancies with one infant death (she had given birth to Francis in December 1876), Mary Quigley could handle no more. She eventually returned home. Sadly, Francis passed away on October 6, 1877, at the age of nine months.

A year-and-a-half later, the unthinkable happened again. On January 14, 1879, “the other” dynamite factory blew up. Six thousand pounds of powder exploded at the Giant Powder Works located at today’s 19th Avenue between Kirkham and Moraga Streets, one mile from the Quigley home. Five workers were killed. Their scattered remains, recovered from great distances, could fill only two buckets. Major property damage was confined to the site where nine buildings were destroyed. Windows were broken as far away as 16th Street.(50)

In this instance, Golden Gate Heights was a bulwark between ground zero and the Quigley home. The most that Mary would have experienced would have been the thunderous noise. But that would have been enough to trigger painful memories and rekindle old fears. Thankfully, the dynamite factories had moved to the East Bay by 1880.

The Godfather and Uncle John

In May 1887, Park Superintendent J. J. McEwen resigned. Heralding an improvement in park politics, William Hammond Hall was persuaded to return as a consultant. He agreed on the condition that John McLaren, a talented Peninsula landscape gardener, be appointed his assistant with the plan that McLaren would eventually become the park’s superintendent.(51) Since Patrick was one of two original park workers hired in 1872 still on the job,(52) it would make sense that he would bring Hall up to date. Observing good administrative practices, Hall introduced Patrick to his new boss, heavily praising Patrick as he had for his 1874 pay raise. No one else possessed Patrick’s knowledge and experience with the park’s history and its needs, making him a gold mine of valuable information for McLaren. Plus, with two sons in the park service, Patrick was a celebrity and a curiosity. John McLaren came to Golden Gate Park on Hall’s high praises, having created beautifully landscaped gardens south of San Francisco from 1873 to 1887. But he came from a privileged background, working for millionaires—Leland Stanford, James Lick, and W. C. Ralston—at a time when millionaires were less common than billionaires are today. Whatever they wanted, they provided McLaren the wherewithal to create their dreamscapes. His employers’ wishes for the very best were their commands, his resources were limitless, and there was no administrative dysfunction. The word no was unheard of.

Not so in San Francisco, where doing more with less was the general practice. For two years, Hall transitioned McLaren into his new job and its new demands, but when W. W. Stow was appointed park commissioner in September 1889, Hall resigned in protest against Stow with whom he had deep personal and political animosities. McLaren kept the title of acting superintendent until the park commission appointed him superintendent on July 29, 1890.(53) Patrick’s extensive park experience would have stood him in good stead with McLaren who likely came to depend on Patrick as his liaison with the men in the trenches, freeing McLaren to deal with administrative/political affairs he didn’t have to contend with during his earlier work south of the city. Thus began a quarter century collaboration between “Uncle John”(54) (McLaren) and “The Godfather”(55) (Quigley).

In the early 1890s, as Uncle John and The Godfather were solidifying their working relationship, several projects were initiated that would change the face of Golden Gate Park. In July 1884, the park commission decided to build a million-gallon reservoir seventy feet below the summit of Strawberry Hill for irrigation purposes.(56) In anticipation of the reservoir’s construction, a road was built to the top of the hill in April 1886.(57) The superlative view from this now-reachable pinnacle attracted multitudes: so many that five years later Thomas Sweeney would build his eponymous observatory on Strawberry Hill’s 420-foot summit.

Patrick’s Road

Times were hard in early 1890 with many men unemployed. A charitable relief fund was created to put as many men as possible to work in the park and pay them $1.50 a day to lay a rough road through the sand from today’s intersection of Transverse and Overlook Drives to the intersection of what is now John F. Kennedy Drive and Bernice Rodgers Way. By March 1890, $6,000 was pledged and work began. John McLaren assigned his most senior foreman and three others to supervise the workers. On, March 11, 150 men were at work. Two days later, 600 men were laboring with shovels and wheelbarrows. Each day the number increased: March 16, 1,000 men; March 19, 1,250 men; March 25, 1,800 men.58 When the 1.5-mile-long rough-cut road was “completed” by mid-April, more than $31,000 had been subscribed. At $1.50 per man per day, that is twenty thousand “man-days” of work between March 11 and April 15, or a daily average of six hundred men working under the watchful (and helpful) eye of Patrick Quigley.

The sixty-foot-wide road still needed to be graded and macadamized—a specialized task for Patrick and his laborers and teamsters. Today this road encompasses Overlook Drive, Middle Drive West, a portion of MLK Drive, and Bernice Rodgers Way.

On February 1, 1891, the park commission granted Thomas Sweeney permission to build his observatory at the top of Strawberry Hill. Sweeney hired and paid for his own carpenters and masons. Patrick and his pick-and-shovel lads had nothing to do with building Sweeney’s observatory, merely the construction of the road to the top of Strawberry Hill that made the observatory possible.

With Strawberry Hill becoming an attraction, the park commission decided to build a lake “two square blocks in size”(59) on its east slope at a cost of $30,000.(60) A month before the lake’s contractual completion deadline of December 1, 1891, the park commission decided to encircle Strawberry Hill, tripling the lake’s size, and making Strawberry Hill an island.(61) As the last massive boulders were inserted on the lake’s Rustic Stone Bridge in August 1893, plans for the publicly financed California Midwinter International Exposition of 1894 were being finalized.

“Patrick’s Road,” constructed 1890.

Courtesy of the San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

McLaren was vehemently opposed to surrendering 160 acres of parkland east of the new lake, claiming it would severely damage the park, but he was powerless. Yet he was right. The fair’s two million visitors left the park in a “deplorable state.” It took sixty men, twelve teams, and months of constant work to repair the damage inflicted on the park.(62)

Eighteen months after the fair’s closing, only the Bonet Tower, the fair’s 266-foot-tall iron and steel iconic symbol, remained standing. It had long overstayed its welcome, and the patience of McLaren and the park commission had been exhausted. On January 11, 1896, an attempt to dynamite the tower’s base and pull it down failed. On McLaren’s orders, Patrick and his crew arrived at the tower early in the morning of Sunday, January 12, 1896, with more dynamite.(63) First, two sticks of dynamite were exploded under each support. Then a trench was dug around the blocks to access the foundations. After three hours of drilling, several six-foot holes were made in the western blocks.

As The Godfather produced the explosives, Uncle John admonished him, “Now don’t be at all sparing with that stuff, Quigley. We want to make a good job of it.”

“Aye, aye, sir,” The Godfather echoed from deep in his trench.

Quigley deposited thirty pounds of dynamite in the blocks, evacuated his trench, prepared his firing apparatus, and announced that everything was ready. The spectators were pushed back, Quigley signaled, and the dynamite did the rest.(64)

The New Century

The twentieth century brought San Francisco a new city charter and new challenges for John McLaren. It also brought the eight-hour workday law, reducing the workday from nine to eight hours for workers like Patrick. The City Charter of 1900 was a new instruction manual on how to run the city. After years of discussion and debate, it had been ratified in 1898, so there were no surprises when it was implemented in January 1900.

John Hays McLaren (1846–1943) was a Scottish-born American horticulturalist. For fifty-three years (1890-1943) he served as superintendent of Golden Gate Park.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Previously, McLaren was responsible for Golden Gate Park, Buena Vista Park, and Mountain Lake Park. Under the new charter he had responsibility for twelve additional squares that had been under the jurisdiction of the superintendent of public streets, highways, and squares.(65) This meant that McLaren had more administrative duties to oversee and had to be at sites all over San Francisco, as well as at City Hall and park commission meetings. It also meant that he would be even less of a gardener and more of an administrator and delegator.

By 1900 the park was practically fully formed. The decades that Patrick had devoted to his godchild were coming to fruition. The great task now was to maintain the progress and development that decades of hard work had accomplished.

The Quigley Family Tree

For forty years, the Quigleys put down roots deep in the soil of Golden Gate Park. This is the fruit of the family tree. Mary and Patrick, but mostly Mary, raised nine children to adulthood in their Little House in the Park. With the children’s twenty-three-year age span, this was a mixed blessing. At times, the older ones could help with family chores involving the little ones. At other times, the sheer number of offspring must have been overwhelming, particularly for Mary. Two Quigley boys married, as did two of the girls. However, the boys did not have children, thus ending the Quigley name; but the girls did have children, so the Quigley line continued.

Charles, James, Thomas, and Joseph

In 1881 the two oldest boys, Charles and James, were the first to get jobs. Nineteen-year-old Charles became a “surfman” at the lifeboat station in the northwest corner of Golden Gate Park. It was the surfmen’s duty to rescue people in danger in the surf off Ocean Beach. Twenty-one-year-old James chose a less adrenaline-fueled occupation as a clerk in a downtown dry good store. The boys continued to live at home in the park.

In 1884, Thomas, now twenty years old, began a forty-three-year career as a downtown office worker in various businesses. The places where he worked are listed in the city directories, but the details of his employment are not known. Thomas was clearly intelligent and industrious to work in a downtown business environment. He never married. In 1885 the “prodigal sons,” James and Charles, joined their father in the “family business” as park workers. Each held different positions over the ensuing years: laborer, teamster, gardener, carpenter, and clerk.

In 1887 and 1888, James was a guard at the House of Correction, San Francisco’s nineteenth-century equivalent of the County Jail. He returned to the park in 1889, where he worked until 1903.

In December 1893, just as the highly anticipated California Midwinter International Exposition of 1894 was about to open, an enterprising businesswoman, the widow Julia Herzo, opened a bar on today’s Lincoln Way near Ninth Avenue—Little Shamrock. She already owned and operated a Little Shamrock in the Richmond District. Anticipating huge crowds descending on the park for the fair, she opened her second Little Shamrock to capture customers coming and going to the fair on both sides of the park.

Not unexpectedly, her clientele included park workers. Although there were strict rules against drinking on the job, after-work imbibing was OK. And, best of all for James Quigley, Little Shamrock was an easy six-block stroll to and from his home in the park.

After a courtship that may have begun as early as 1893, James and the widow Herzo were married in 1901. At the age of forty-one, James left the family home and moved six blocks down Lincoln Way (then known as H Street) to set up housekeeping above the Little Shamrock at 807 H Street. He continued in the park service for two more years while with Julia. In 1903 he left the park service to work full time at Little Shamrock. For the next nine years James was the popular saloon keeper of a popular neighborhood bar, with his name on the Little Shamrock sign.

Little Shamrock circa 1905 at 807 H Street (now Lincoln Way). People in photo are not known.

Photo: courtesy of Little Shamrock

San Francisco Chronicle, June 9, 1907

On the night of June 8, 1907, at the age of 45, Charles became the fourth Quigley offspring to die in Golden Gate Park following his infant siblings who died in the 1870s and 1880s. He was killed by a hit-and-run driver a quarter mile from home near the park police station.

James, the oldest Quigley child, was active in local Democratic Party politics, holding office in many political clubs. He never ran for public office, but he organized events supporting Democratic candidates and local partisan issues. He and Julia did not have children. Julia had three from her previous marriage, two of whom lived with James and Julia above Little Shamrock. James died suddenly in November 1912 at the age of fifty-two.

The youngest child, Joseph, was the third apple to drop near the Quigley family tree. After two years of office work for his brothers George and John, he joined the park service at age twenty-one and worked from 1902 to 1912. Thus, for about a year, four Quigley men would share dinner and work stories at the Little House in the Park.

Joseph never married and died at the age of thirty in April 1912.

These four Quigley men—Patrick, James, Charles, and Joseph—left us a treasured legacy: Golden Gate Park.

Elizabeth, John, and George

At age twenty-three, Elizabeth was the first Quigley child to leave home when she married Doctor John R. McMurdo, a widowed Englishman eleven years her senior, in April 1888. Dr. McMurdo graduated from the California College of Pharmacy in November 1887.(66) That year, according to the city directory, he also worked as a nurse at the Alms House, about a mile south of the Quigley home. Somewhere in that geographical area, the paths of Elizabeth and Dr. McMurdo crossed and “one thing led to another.”

Elizabeth Quigley’s wedding portrait, age 23, 1888.

Photo: courtesy of the Ledfors family

Following their wedding, the newlyweds moved to Buchanan and Ellis Streets in the fashionable Western Addition. On February 7, 1889, the first Quigley grandchild (a girl, Lavinia) was born to the McMurdos.

Dr. McMurdo’s contribution to the Quigley family was much more than starting a new limb on the Quigley family tree. Whether cause or coincidence, just as Dr. McMurdo entered the lives of the Quigley family, John Quigley began to follow a path that would lead to his becoming a medical doctor. In 1887, while still a pharmacy student, Dr. McMurdo worked as a nurse at the Alms House. According to the city directory, James Quigley also worked as a nurse at the Alms House in 1888 and 1889. Whether their shifts overlapped is not known, but by April 1888 Dr. McMurdo was a member of the Quigley family, and James was on his way to a medical career.

After his stint as an Alms House nurse, the city directory lists James as a medical student for the next two years (1890–91). He then attended the Willamette Medical College in Portland, Oregon,(67) returning to San Francisco as a physician and surgeon with a downtown office. Without doubt, George Quigley’s professional career was directly influenced by Dr. McMurdo, who very likely guided and mentored him.

By 1890 Dr. McMurdo was an established druggist/pharmacist. In June 1890 he placed a newspaper ad:

WANTED—A boy, residing with his parents, to learn the drug business. Apply at McMurdo’s Pharmacy, cor. Ellis and Buchanan.(68)

Nineteen-year-old George Quigley, still living at home, applied for the position and was hired by his brother-in-law. He worked for Dr. McMurdo for four years. After a two-year gap in the city directory, George appears as a student in the 1896 city directory living in Golden Gate Park. The 1897 city directory lists him as a druggist at 1501 Waller Street. This would be his lifelong career. At that time the closest pharmacy for the emerging Haight-Ashbury neighborhood was one mile to the east at Haight and Steiner Streets, making George Quigley the first “drug dealer” in the Haight-Ashbury, seventy years before the Summer of Love.

Three generations of Quigleys, 1912. Left to right: Bridget Quigley Guedet (Patrick’s daughter), Patrick, Grandson Louis on his lap, unidentified man.

Photo: courtesy of Susanne Burzinski (née Guedet)

The next year John joined George to form a professional/family collaboration at 1501 Waller Street from 1898 to 1907. John was one of only ten physicians west of Divisadero Street and south of the park in 1898. In December 1898, the Examiner called Dr. Quigley “a prominent citizen.”(69)

Youngest brother Joseph joined the two medicos for two years as a clerical helper (1899–1900) before going to work in Golden Gate Park.

During Elizabeth Quigley McMurdo’s ten-year marriage, she gave birth to six children, three boys and three girls. She died in childbirth on December 16, 1898, at the age of thirty-three with what would have been her seventh child. Her children are one of today’s two branches of the Quigley family tree.

On July 17, 1898 (five months before Elizabeth’s death), a nine-room residence at 115 Beulah Street went on the market for $5,000.(70) Six months later the motherless McMurdo family moved in.(71) For the children, ranging in age from one to ten years, this was an ideal location. They were a half mile from “gramma and grampa’s farm”(72) in the park and just half that distance to Uncle George’s and Uncle John’s office. The half-mile trek to the Quigley “farm” would have been quite the outing for the older youngsters. One block from their Beulah Street home they would cross Stanyan Street into Golden Gate Park’s nursery and stables. Thousands of plants and seedlings waiting to be transplanted must have had the appearance of a forest or a jungle. Horses were ubiquitous in 1900, but the children undoubtedly enjoyed petting the working animals at the adjoining park stables. The “farm” promised more fun with their grandparents and aunts and uncles who still lived there.

For two years they experienced the childhood dream of living just a block from the Haight Street Chutes, a large amusement park with animals, games, rides, live performances, and balloon ascensions. They could easily hear the roar of the lions from their home.

In January 1901, Dr. McMurdo remarried to Mary E. Burke, eventually adding two sons and a daughter to the McMurdo household.

Dr. John Quigley married in 1901. He and his wife (nee: Evelyn Haubrich) lived in the 1501 Waller Street building until 1907, when he bought a magnificent home at 1627 Tenth Avenue. That same year, he moved his medical practice four blocks away to 501 Cole Street at Page Street, and later to 1595 Haight at Clayton. The couple did not have any children.

George never married and continued to live at the Quigley home in Golden Gate Park.

The Other Quigley Girls

Youngest daughter Bridget was the first Quigley child born in Golden Gate Park, in April 1873. In 1911, at age thirty-eight, she married Louis Guedet, a printer by trade. Mr. Guedet enlisted in the First California Infantry Volunteers a week after war with Spain was declared, arriving in the Philippines on June 30, 1898. His regiment was involved in several battles, including the Battle of Manila. He attained the rank of sergeant.

Bridget lived the rest of her life with her husband at 3231 Market Street where they raised their two sons, Louis (1912–1993) and Joseph (1914–1979), who constitute the second branch of the Quigley family tree. Her husband Louis died in 1947. She was grandmother to two children: Philip and Suzanne.

Bridget died at age seventy-seven in 1950, the last of the Quigleys of Golden Gate Park.

Of the three Quigley girls, all we know of the middle daughter, Mary, is that she was born in Mariposa County in 1867 and never married. She passed away in 1944 at the age of seventy-seven.

Bridget Quigley Guedet (Patrick’s daughter) and sons Phillip (seated) and Louis (standing).

Photo: courtesy of Susanne Burzinski (née Guedet)

Epilogue and Legacy

died at home of the same infectious disease. Patrick’s oldest son, James, died suddenly on November 4 and was buried on November 6, 1912. On the day of James’ funeral, Edward Guedet, father-in-law of Patrick’s daughter Bridget, died.

On November 14, 1912, Patrick passed away in his Golden Gate Park home of forty years. His obituary suggests that his cause of death was due to an injury he sustained two weeks earlier. His death certificate lists chronic heart disease as the primary cause. The two (injury and heart disease) are not mutually exclusive. What is extraordinary is that his death certificate notes that Patrick had been diagnosed with heart disease eleven years earlier, but he continued to work all that time—into his eighties—with a heart condition. On November 7, seven days before he died, Patrick made out his will, hinting at yet another cause of death: grief and a broken heart. Today it is known as broken heart syndrome or takutsubo cardiomyopathy, a reaction to a surge of stress hormones triggered by an emotionally stressful event.

In addition to chronic heart disease and a recent injury (the nature and seriousness of which are unknown), Patrick sensed that, at age eighty-three, his working days were numbered and that he would not be returning to the park he had loved and nurtured for forty years: the park in which he and his family had lived; in which his children were born and died; in which he had worked six days a week, nine (then eight) hours a day

Tragedy visited the Little House in the Park three times in 1912, ending forty years of Quigley residence there. On April 12, 1912, youngest child Joseph, a park employee, died at home at age thirty-one of acute capillary bronchitis. Two weeks later his mother, Mary (Patrick’s wife of fifty-four years), with his sons; or to the home that was contingent on his continued employment. After eleven thousand working days on the job his spirit told him, “Our work here is done. It’s time for us to go.”

The Patrick Quigley Mystery

Why did Patrick continue working until he literally died on the job at age eighty-three? There are two possible answers: he had to, or he wanted to. Indirect clues indicate that he wanted to keep working. On September 26, 1895, the park commission granted John McLaren authority to “employ and discharge all the employees of the park whenever it is for the interest of said park.”(73) By then, Patrick was sixty-six years old—the oldest park worker. San Francisco had no retirement pensions for city work- ers, except for police and fire. There was no Social Security safety net. It is not known if there was a mandatory retirement age for city workers, but it is clear that McLaren could let go of workers who were dead weight or liabilities to the park. Clearly, Patrick at age sixty-six was an asset to the park worthy of continued employment.

Following his death, Patrick’s estate was appraised at $29,254.14. This consisted of personal property valued at $13,254.14 and Outside Lands Block Number 732, bounded by 37th and 38th Avenues and J (Judah) and K (Kirkham) Streets valued at $16,000.(74) Patrick had bought this property in March 1890 from Hugh Jones.(75) No price was noted, but this block, two blocks south of the park in the Sunset District, was undeveloped desert at the time. Clearly this was an investment.

Was this property Patrick’s and Mary’s retirement plan? The “personal property” consisted of a few home furnishings valued at $100 and three savings accounts containing $13,154.14,76 the equivalent (according to various computations) of more than $300,000 today. By 1900 Mary and Patrick had no dependents. All their children were grown, although some still lived at home.

Why would Patrick want to stay? One compelling reason is that Uncle John wanted or needed Patrick to stay and so persuaded him to do so. McLaren’s job was becoming more and more complex, and he needed trusted and reliable people by his side, regardless of age.

The Godfather had a great sense of loyalty to Uncle John. With the tidy nest-egg the Quigleys had, they could have left their Little Home in the Park at almost any time and lived comfortably elsewhere. But they didn’t. They didn’t need the job, or the income, or the rent-free home, but they chose to stay. Death had one more Quigley victim to claim in Golden Gate Park. On September 5, 1917, Dr. John Quigley’s car overturned on today’s Martin Luther King Drive near Seventh Avenue. He died a week later of a fractured skull. He was the eighth Quigley to die in the park.

When Patrick Quigley joined the park service in 1872, Golden Gate Park, his godchild, was in its embryonic stage of development. When he died forty years later, on November 14, 1912, he had ushered his godchild to full maturity.

At the park commission meeting of November 28, 1912, a motion passed unanimously: “Patrick Quigley, who departed this life on November 12, [sic] 1912, after forty-two (42) years [sic] of faithful and intelligent service in the employment of the park commissioners, was allowed a full month’s pay.” Such a tribute to a park employee was unprecedented in park commission history.

After Patrick’s death, the adult Quigley children (Thomas, born in 1864; Mary, 1867; and George, 1870) still living in their home were forced to vacate their park-provided residence in which they had lived nearly their entire lives. They moved across the street to 1210 Fourth Avenue, where they lived together until George died in 1922, followed by Thomas ten years later. Mary passed away in November 1944 at the age of seventy-seven.

At the park commission meeting of February 16, 1913, John McLaren recommended that the Quigley home be demolished and the site be planted with shrubs. No action was taken, and the building stood empty. In 1914 the house received brief public notoriety as the neighborhood haunted house.(76) A week later it was destroyed in an arson fire.(77) Undoubtedly, the three Quigley children living on Fourth Avenue suffered the heartbreak of witnessing the only home they ever knew sit vacant and deteriorating, and then its destruction by fire.

The Quigleys represented the archetypal mid- to-late-nineteenth-century American working-class family: the husband/father toiling at manual labor six days a week (if lucky, five-and-a-half days), while the wife/mother remained at home raising the children.

In their time, the Quigleys were institutions in the newly emerging Haight-Ashbury and Inner-Sunset neighborhoods, and in the established Golden Gate Park Community. With four Quigleys working in the park, the Quigley men were a feature and a fixture. Whether they worked together on the same projects under their father’s leadership, or on other tasks in the park, from the Panhandle to the ocean, the Quigley spirit permeated the park for forty years.

All parents hope their offspring will have better lives than their own. With the exceptions of Charles and Joseph, the Quigley boys ascended the socio-economic ladder. John and George became professionals who provided medical and pharmaceutical services to the growing Haight-Ashbury and Inner-Sunset neighborhoods at the turn of the twentieth century and beyond.

Thomas’s white-collar occupations were a symbol of success.

Little Shamrock, the home and business for a decade that James married into via the widow Julia Herzo, is still as popular as ever at 807 Lincoln Way, near Ninth Avenue.

Two of the girls married well, one to a medical doctor and another to a successful printer who owned his own business.

Today, 112 years after Patrick’s death, Golden Gate Park is a world-famous man-made miracle. It is also a thousand-acre hall of fame; it is a who’s-who with monuments and memorials to nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first century powerful and privileged, none of whom lifted a finger to help create or maintain Golden Gate Park.

Today there is nothing to remind park visitors seeking relaxation, recreation, or rejuvenation that Patrick and his family ever existed. Except for Patrick’s obituary and Golden Gate Park.

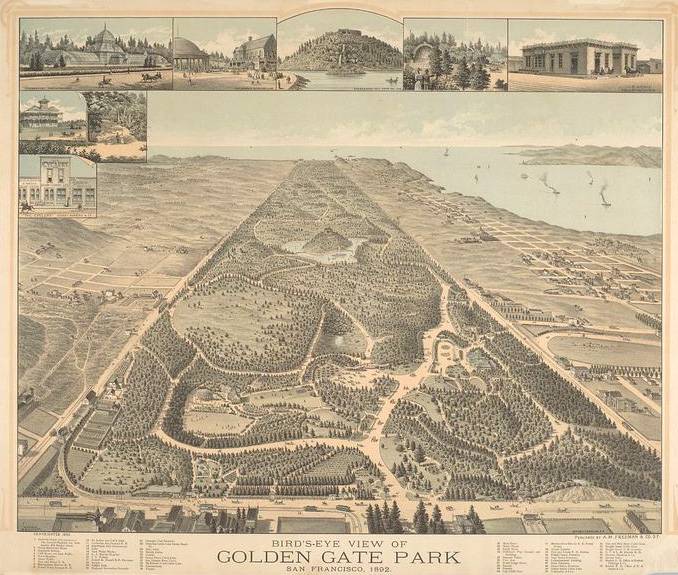

Bird's-eye view of Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, 1892. View from east end of park looking towards Pacific Ocean; seven marginal images at top depicting sites of interest. Legend includes cable lines and railroads.

The author is especially indebted to the descendants of Mary and Patrick Quigley for sharing their treasured family memorabilia, which greatly enriched this history of a remarkable San Francisco family.

Angus Macfarlane has lived in San Francisco since 1954. Over those decades he has explored Golden Gate Park from childhood to adulthood, never failing to find something new and remarkable. This is his gift to Golden Gate Park, to the people of San Francisco, and to the Quigley family.

Notes:

1. Park commission minutes Vol. 1; April 4, 1870–July 28, 1908, 2.

2. Park commission minutes, July 5, 1870, 5.

3. Daily Alta California, May 24, 1853, 2.

4. Daily Alta California, November 16, 1853, 2.

5. Frank Soulé, John H. Gihon & James Nisbet, The Annals of San Francisco, 161.

6. Daily Alta California, November 27, 1853, 2.

7. Daily Alta California, April 18, 1854, 2.

8. San Francisco Examiner, January 20, 2002, c6.

9. Daily Alta California, August 21, 1862, 1.

10. Daily Alta California, January 20, 1867, 1.

11. Daily Alta California, February 8, 1864, 1.

12. Daily Alta California, March 3, 1866, 2.

13 San Francisco Municipal Reports 1869–70, 560.

14. Park commission minutes, November 17, 1870, 8.

15. San Francisco Bulletin, December 29, 1919, 14.

16. San Francisco Examiner, March 20, 1872, 3; San Francisco Municipal reports 1870–71, 400.

17. Daily Alta California, December 17, 1861, 1; The Argonaut: Journal of the San Francisco Historical Society, 23:2, W2012, 20–37.

18. Park commission minutes, May 12, 1871, 13.

19. Initially, William Hammond Hall’s title was engineer. However, since this was soon replaced by superintendent, and all subsequent park leaders had that title, it is simpler to refer to him as superintendent.

20. Park commission minutes, August 14, 1871, 14.

21. Park commission minutes, March 7, 1872, 22 and April 3, 1872, 25. The park commission minutes of March 7, 1872, show that $5,490 was paid to W. H. Hall for payroll for park improvements for February. The April 3 minutes show that $7,204 was paid to W. Hall for payroll for March. Separate items in the April payroll are for W. H. Hall’s $250 salary as engineer for March, Secretary Mulder’s $75 salary for March, and Patrick Owens’ (now reclassified as nurseryman) $75 salary for March. Clearly, Engineer Hall was not receiving two paychecks. One payroll item for $250 was his monthly salary. The other items ($5,490 and $7,204) were for Mr. Hall to disburse to the non-appointed laborers: i.e., the dollar-a-day men.

22. Park commission minutes, June 6, 1872, 33.

23. Park commission minutes, May 1, 1872, 28; June 6, 1872, 33.

24. US census, 1870.

25. San Francisco Municipal Reports, 1867–68, 560–64.

26. 1900 census.

27. San Francisco Examiner, November 16, 1912, 8; Merced Star, November 21, 1913, 3.

28. 1900 census.

29. Raymond Clary, The Making of Golden Gate Park: The Early Years: 1865–1906 (California Living Books, 1984), 22.

30. Park commission minutes, November 20, 1873, 93; December 10, 1873, 96.

31. San Francisco Chronicle, April 24, 1872, 2.

32. San Francisco Municipal Reports, 1873–74, 486.

33. San Francisco Municipal Reports, 1871–72, 39, Sections 9 & 12.

34. San Francisco Municipal Reports, 1873–74, 489.

35. Ibid., 491.

36. Park commission minutes, May 11, 1874, 11.

37. San Francisco Bulletin, December 25, 1919, 4.

38. Raymond Clary, The Making of Golden Gate Park: The Early Years: 1865–1906, 26–27.

39. Park commission minutes, December 10, 1881, 312.

40. San Francisco Chronicle, July 7, 1882, 1.

41. Ibid

42. San Francisco Chronicle, January 30, 1887, 3.

43. San Francisco Municipal Reports 1874–75, 232; 1880–81, 192; 1881–82, 252. There were no attendance numbers after the 1881–82 statistics since the gate keeper/attendance keeper was one of the employees fired.

44. San Francisco Municipal Reports, 1881–82, 248.

45. San Francisco Bulletin, December 22, 1919, 8.

46. Daily Alta California, San Francisco Chronicle, San Francisco Examiner, June 22, 23, 1872.

47. San Francisco Bulletin, San Francisco Chronicle, San Francisco Examiner, Daily Alta California, December 22, 1872.

48. San Francisco Chronicle, San Francisco Examiner, Daily Alta California, San Francisco Bulletin, June 9, 1877.

49. San Francisco Municipal Reports, 1881–82, 245.

50. Daily Alta California, San Francisco Chronicle, San Francisco Examiner, San Francisco Bulletin, January 15, 1879.

51. San Francisco Examiner, September 4, 1960, 64.

52. Patrick Owens continued to work till he died in 1899.

53. Park commission minutes, July 29, 1890, 225.

54. The earliest reference of “Uncle John McLaren” was San Francisco Chronicle, December 26, 1926, 44. I chose to employ this nickname to emphasize the collegial relationship between Patrick Quigley and John McLaren in regard to Golden Gate Park.

55. Patrick Quigley’s contribution to the growth and nurturance of Golden Gate Park is analogous to a child and a godparent, thus the moniker.

56. Daily Alta California, July 22, 1884, 8; Daily Alta California, February 11, 1885, 8; San Francisco Examiner, February 22, 1885, 5.

57. San Francisco Chronicle, April 21, 1886, 5.

58. Daily Alta California, March 17, 1890; San Francisco Examiner March 20, 1890, 6; San Francisco Examiner, March 26, 1890, 3.

59. San Francisco Chronicle, May 22, 1891, 3.

60. Park commission minutes, June 29, 1891, 244; August 12, 1891, 254–55.

61. San Francisco Examiner, October 26, 1891, 3.

62. San Francisco Municipal Reports 1894–95, 71.

63. McLaren was not acting as a rogue operative, but under the direction of the park commission after an ultimatum to remove the tower by December 17, 1895, was passed by the park commission on December 14, 1895, (minutes, page 361) but ignored by the owners.

64. San Francisco Examiner, January 13, 1896, 12.

65. Park commission minutes, January 10, 1900, 198, The new squares were Alamo, Alta, Lafayette, Hamilton, South Park, Union, Washington, City Hall Grounds, Jefferson, Garfield, Columbia, Portsmouth.

66. San Francisco Chronicle, November 9, 1887, 3.

67. San Francisco Examiner, June 26, 1901, 3.

68. San Francisco Call, June 24, 1890, 4.

69. San Francisco Examiner, December 19, 1889, 2.

70. San Francisco Call, July 17, 1899, 14.

71. San Francisco Call, January 13, 1899, 8.

72. This is a name given by the Quigley grandchildren to Patrick and Mary’s home in the park. Email November 17, 2023, from Judith Ledfors, great-great-granddaughter of Mary and Patrick Quigley.

73. Park commission minutes, September 26, 1895, 357.

74. The Recorder April 12, 1913, 10.

75. San Francisco Examiner, March 15, 1890, 10.

76. San Francisco Examiner, May 11, 1914, 3.

77. San Francisco News, May 18, 1914, 2.