Block 3706: Journey to a New City

Block 3706: Journey to a New City

Historical Essay

by David Grayson

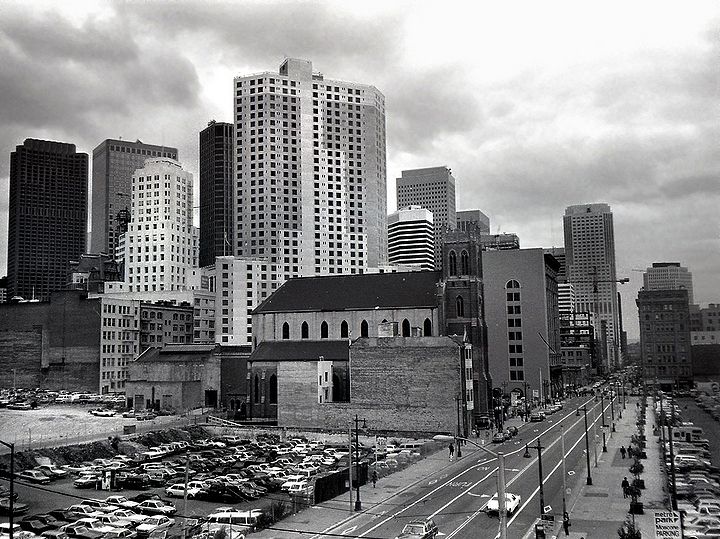

Photo looking east from 4th and Mission, 1984.

Photo: Dave Glass

In an influential essay, “Here is New York,” E.B. White described New York City as comprising “tens of thousands of tiny neighborhood units.” These were communities unto themselves, and White reflected that just a short stroll away from their block a local resident “is in a strange land.”(1) Like New York, a single block in San Francisco can be home to many residents and possess a long history. As a San Francisco native, I have experiences in most parts of the city. What surprised me, however, was my history with one particular block, #3706. Its north and south borders are Market and Mission; 3rd and 4th Streets are its east and west sides.(2) Starting in childhood, I witnessed the transformation of this particular block, including the construction of landmark buildings, a new public square, and the vanishing of interior lanes—all of which I later realized represented a new city.

Like its neighbors along Market Street, block 3706 straddles two distinct neighborhoods. Mission, 3rd, and 4th Streets are firmly part of SoMa. The Market Street side belongs more to the Union Square shopping district. This distinction is reflected in the Department of City Planning book, Blocks 3630-3799, 1960-65, where a red line splits block 3706 into two parts, with the space south of the line stamped with the words “Redevelopment Area Project D-1.”(3)

This redevelopment area was part of the city's efforts to wholly transform SoMa from a low rent community in the 1960s to a more corporate and tourist-based destination. Many SoMA residents were single men who had first visited the city through military service in transit to the Pacific theater in the Second World War. Some returned after the war and found employment in the shipyards and industrial plants in SoMa. Gayle S. Rubin records that the neighborhood “housed the bus terminals and the cheap hotels for transients, seamen, and other single working men.”(4)

In SoMa, redevelopment would lead to the removal of 4,000 residents and 700 small businesses.(5) In Infinite City: A San Francisco Atlas, Rebecca Solnit describes pre-redevelopment SoMa as a “neighborhood of residential hotels, pawnshops, small shops and manufactories, diners, and taverns …” On a map, Solnit displays businesses and residences on block 3706 (as well as adjacent blocks). On just the short 4th Street stretch, there are twenty businesses.(6)

The variety is impressive, and includes two bars (McCarthy’s tavern and the News Room tavern), four restaurants (Sweet Spot, Cozy Corner, Cairo, and Fourth Street Lunch), two hotels, and a theater. There were three cigar stores, two shoe shine stands, and—symbol of a bygone era—a typewriter shop. A similar density was evident on the Mission Street and 3rd Street sides. For example, next to the St. Patrick Church rectory was a church supply store. On the other side, maybe surprisingly, sat a “carnival goods” seller. In stark contrast, when I was working on the block in the late 2000s and early 2010s, I walked the 4th Street side innumerable times from my office to the fitness center at the Marriott hotel. I only passed one business on that side: Ross Dress for Less.

In One Man’s San Francisco, Herb Caen chronicles the sudden transformation of the neighborhood, describing the scene at the corner of 4th and Mission (now home to the Metreon and Target) as a cluster of businesses is demolished by a bulldozer:

“I tried to remember what had been there just a few hours before—for at least fifty years—but out of sight, etc. Certainly there had been a saloon, featuring watery beer and wheyfaced old-timers who never took their hats off. At least one bookie joint, which had its front light on when it was safe to enter. A skinny shoeshine stand, one door wide, run by a clean old man who was careful not to get polish on your socks … Gone, like that. Fwoosh.”(7)

The Market Street side of 3706, oriented toward Union Square, evolved as well. Retail grew around Union Square after 1906. By 1940, there were 17 large retail stores between Market and Sutter streets. Growth continued in subsequent decades, and Gregory J. Nuno notes that by 1985 “the total retail footage around Union Square had become one of the greatest concentrations in the world.”(8)

Due to these developments in both SoMa and Union Square, block 3706 today is a dramatically different place. Like neighboring blocks, it’s no longer a working-class residential community. The focus shifted to new cultural institutions, including the Contemporary Jewish Museum and the in-progress Mexican Museum. One notable aspect of both is that they are built on, and incorporate, historic structures. This blending of past and present at least symbolically pays homage to the older neighborhood.

The Contemporary Jewish Museum (CJM), designed by architect Daniel Libeskind, repurposed the PG&E Jessie Street power substation built in 1881. The substation was damaged in a fire months before the 1906 earthquake and was damaged again during the quake.(9) Later shuttered by PG&E, the Redevelopment Agency planned to demolish the classical brick structure but preservation groups succeeded in getting it landmark status in 1976.(10)

The museum features almost glowing blue cubes that seem to sprout from the brick substation. The San Francisco Chronicle urban design writer John King wrote that “unlike most buildings in the neighborhood—a redevelopment district conceived in the 1960s with the razed-block mentality common to the era—the Contemporary Jewish Museum blends old and new.”(11)

A corner of the façade of the Mexican Museum.

Photo: David Grayson

The Mexican Museum’s design has followed a similar trajectory. Opening onto Jessie Square, it occupies four floors of 706 Mission, a structure that is comprised of a new residential tower attached to the Aronson office building, a survivor of the 1906 earthquake.(12) The exterior multi-floor façade wraps around the front and resembles a topographical map which represents migrations (human, flora, wind, and more) between Mexico and San Francisco.(13)

It’s crucial to recognize, however, that although these two buildings pay tribute to the past, they are ensconced in the new reality of a wealthy enclave. For example, the tower that houses the Mexican Museum is also home to the high-end Four Seasons Private Residences.

The museums are flanked by large-scale hotels, part of the engine of tourism. Next to the Mexican Museum is the Hyatt Regency. On the other side, neighboring historic St. Patrick Church, was probably the most controversial development on the block, the Marriott Marquis hotel. The building was nicknamed the “jukebox” by the Chronicle architecture critic Allan Temko. It unwittingly became another chapter in city earthquake lore when it opened to guests on October 17, 1989—the day of the Loma Prieta earthquake. Longtime Chronicle columnist Carl Nolte noted that the building “swayed like a tree in a windstorm.” Claudia Coleman, a cocktail waitress working in the hotel’s The View Lounge said that “fire sprinklers went on, soaking everything and everybody.”(14)

But, here too, there is concealed history. An attentive passerby will see a wall plaque on the 4th Street side of the Marriott that describes how this spot was a major military induction center during the Second World War.

Yerba Buena Lane.

Photo: David Grayson

Block 3706 is also unique in that the interior streets have been reconfigured, two of them removed. Jessie Street was replaced by Jessie Square, a plaza that sits in the lap of the new buildings. As a kid, I remember my parents parking in an asphalt lot that became part of Jessie Square. The firm that built Jessie Square also created the pedestrian-only Yerba Buena Lane, which connects foot traffic on Market Street with the museums and Yerba Buena Gardens to the immediate south. Both square and lane were completed in 2008, and a handful of eateries are located there. A second interior street, Stevenson, is parallel to Jessie and runs through most of SoMA. Stevenson is now ruptured in the middle of the block. Finally, block 3706 has one more ground-level secret to reveal: a “ghost” alley. Opera Alley was a short lane that ran partly into the block from Mission Street, behind the Aronson building. It’s present in the Block Book, 1960-65 but absent in later editions.

Block 3706 continues to experience shifts. Signs of the pandemic linger in the empty storefronts along Market and 3rd streets. Notably, both the CJM and the Mexican Museum are facing significant challenges. In response to a 50% drop in attendance since reopening post-pandemic, the CJM closed for one year in order to assess its future.(15) The Mexican Museum has faced fundraising challenges that could jeopardize its opening.(16) In terms of real estate, according to the Chronicle, the new condominium tower that hosts the Mexican Museum has been slow to sell units.(17) Of course, economic change is cyclical. But it would be naïve to assume that trends like remote work and the impact of ecommerce on brick-and-mortar businesses will fade with no lasting mark.

For any longtime resident of a city, compounding change is an unsettling experience. It’s not always the first change you encounter that is the most jolting; it’s sometimes when that change is superseded by another. Each new development prompts me to recognize that at some point my own story with block 3706 will end. Of course, before that time the block may surprise me again with another chapter.

Notes

1. E.B. White, Here is New York. New York: The Little Bookroom, 1999: 34, 36.

2. Engineer Map and Block Numbers. San Francisco Planning. March 2007.

3. Vol. 26. Blocks 3630-3799, 1960-65. San Francisco Department of City Planning.

4. Gayle S. Rubin, “Redevelopment in South of Market,” FoundSF.org.

5. Ibid.

6. Rebecca Solnit, Infinite City: A San Francisco Atlas. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2010: 85-86.

7. Herb Caen, One Man’s San Francisco. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1976: 206.

8. Gregory J. Nuno, “Union Square After 1906,” FoundSF.org.

9. “The CJM Building: History,” Contemporary Jewish Museum website.

10. Woody LaBounty, “Heritage 50: New Life for Jessie Street Substation,” San Francisco Heritage. February 25, 2021.

11. John King, “Museum's bold design vibrantly blends old, new,” SFGATE.com. June 8, 2008.

12. James McCown, “In San Francisco, the historic Aronson Building gets a second life as a neighborhood anchor,” The Architect’s Newspaper. March 25, 2022.

13. TEN Arquitectos website.

14. Carl Nolte, “Shaky opening 25 years ago for S.F.’s ‘Jukebox Marriott’ hotel,” SFGATE.com. October 17, 2014.

15. Tony Bravo, “Why the S.F. Contemporary Jewish Museum is closing for a year,” San Francisco Chronicle. November 14, 2024.

16. Laura Waxmann, “Downtown S.F. museum in trouble after missing key fundraising deadline,” San Francisco Chronicle. June 23, 2025.

17. Laura Waxmann, “One of S.F.’s luxury hotels is scheduled for auction. Here’s how a sale could go down,” San Francisco Chronicle. September 24, 2024.