Esta Noche Was More Than a Bar

Historical Essay

Joshua Alvarez

It Was a Blueprint For Liberation

Esta Noche bar on 16th Street at Weise Alley.

Photo: Joshua Alvarez

| From 1979 to 2014, Esta Noche, a bar for the queer latino community, serves as a space for protection, empowerment, and resilience. This bar was a living blueprint for liberation, a space built by and for people often excluded from dominant queer and Latine narratives. This meant culture and resistance coming together through performance and care. This article argues that Esta Noche functioned as a crucial space for survival and joy, where the queer Latino community could resist racism and homophobia. Drawing from oral histories, community archives, and local reporting, this essay shows that spaces like Esta Noche are not peripheral to social movements, but central to how those movements heal and endure. |

As one of America’s queerest cities, San Francisco is often remembered for its bold celebration of identity. This is a city that historically celebrated its pride through deep connections to queer spaces, activism, and organizing. From the early marches following Stonewall in New York to the first “official” pride parade on Sunday, June 25, 1972, the city has long stood at the forefront of queer resistance (1).

Much of this visibility became concentrated in the Castro District, which emerged in the 1970s as the symbolic heart of gay life in the city (2). Once a working-class Irish Catholic neighborhood known as Eureka Valley, the Castro transformed into a “gay mecca” as thousands of queer people, many discharged from the military during WWII, settled there and built a gay sanctuary (3). It became home to organizations like the Tavern Guild and the Mattachine Society, the site of Harvey Milk’s historic election, and the epicenter of LGBTQ self-help during the AIDS crisis (4).

But visibility even within the queer community was incredibly segregated. The Castro, while important, was largely shaped by white, affluent gay men (5). For many queer and trans people of color a stark exclusion existed in these spaces. In contrast, the Mission District home to a working-class, immigrant, and culturally rich Latine population became a more accessible and affirming neighborhood (6). It was here that many queer Latinos found a sense of belonging.

In the 1970s, groups like the Gay Latino Alliance (GALA) organized politically and socially in the Mission, challenging both homophobia in Latino spaces and racism in queer ones (7). Being in the Mission District at the time, and being so close to the Castro, the group was fundamentally made up of people who were trying to bridge two parts of their identity. That choice of space, culture, and solidarity laid the groundwork for what followed.

In 1979, GALA members Anthony Lopez and Manuel Quijano opened a bar at 3079 16th Street that would become a cornerstone of the queer Latino community in San Francisco (8). The Founders used this space for the organization’s meetings as they saw Esta Noche as a refuge for Latinos (9). As the first Latino gay bar in the city, it offered something rare: a space where queer, brown, working-class, and Spanish-speaking people could show up unapologetically.

Esta Noche patrons get up-close and personal with drag queen, January 1990.

Photo: © Rick Gerharter

January, 1990.

Photo: © Rick Gerharter

Yolanda del Rio, August 30, 1996, at Esta Noche

Photo: © Rick Gerharter

The bar’s creation was a direct response to the layered exclusions queer Latinos faced. Lopez and Quijano were no strangers to these barriers. Both founders were constantly denied entry into the popular white gay bars in the Castro, often being told they did not belong (10). When attempting to acquire permits for their own place, they were met with resistance from city officials who seemed to have no problem approving bars for white business owners (11). This, however, did not stop Lopez and Quijano. With support from their community, they were eventually able to open the doors of Esta Noche.

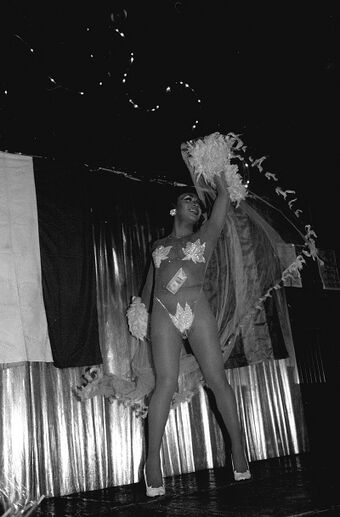

Robin, dancing at Esta Noche, August 30, 1996.

Photo: © Rick Gerharter

What they built became far more than a bar. It became a place where drag, politics, grief, and joy all came together. For many years, the bar served as a haven for queer Latinos. Attendees were able to freely speak Spanish, listen to Spanish music, wear what they wanted, and dance how they felt, without fear. From drag performances to cumbia, bachata, and all the Latino hits, Esta Noche created a space full of joy. A space representing visibility, resistance, love, belonging, home.

Among those whose lives were transformed by Esta Noche is Vivian Lopez, whose first visit opened a door in her heart; Her oral history captures how life-changing a single night can be.(12) Vivian was born in Nicaragua and came to San Francisco when she was eleven. Growing up, she always felt different. Often she played with girls and admired boys. What made all these things feel off to Vivian was every time she saw herself in the mirror, she saw someone she did not recognize. Vivian Lopez was a trans woman. By high school, she knew she was a girl but kept her feelings mostly to herself. It wasn’t until a friend took her to Esta Noche when she was about nineteen that everything shifted.

That night, she saw a drag show for the first time. She had not begun her transition process yet, but watching gender-fluid and drag queens perform opened a new door. “I said, when I dress up, that’s what I want to look like,” she recalled (13). “Because they were so pretty what's there. I thought wow, that's how I want to look” (14). That experience was a turning point. Soon after, Vivian began hormone therapy through a doctor at a local clinic, as she met others at Esta Noche who were also transitioning (15). They became a support network, showing her that she wasn’t alone.

For Vivian, Esta Noche symbolized the place she was first given permission to imagine herself and her future. Esta Noche was able to affirm her identity. Vivian’s story echoes across the many spaces, bars, and clubs today, serving as a reminder to protect the places that help queer communities thrive.

Esta Noche also played a serious role in community health. During the AIDS epidemic, it was one of the few places reaching out to queer Latine people with information and support. The bar partnered with the Stop AIDS Project to distribute more than 17,000 condoms (16). It held fundraisers and launched events like Mr. and Miss Safe Latino to raise awareness (17). These were grassroots public health efforts rooted in love and urgency.

Adela Vazquez.

Image: Joshua Valdez

Cuban-American trans activist Adela Vazquez was a key figure during this time. She performed at Esta Noche and helped organize Las AtreDivas, a group that used art and drag to raise money for people with HIV, especially trans women who were often left out of mainstream responses (18).

Of course, the bar wasn’t perfect. Some lesbian patrons felt excluded in what was often a male-dominated space. Diana Flores responded by creating a new space called Colors that centered queer Latinas (19). These moments of tension were important because they showed that even inclusive spaces need to keep evolving.

Figure 2. Image of Bay Area Reporter Newspaper

By 2014, the bar was facing a different kind of threat. Rent had skyrocketed from $360 in 1979 to nearly $7,000 a month (20). This was one of the many barriers in place in an ever growing gentrified community. In 2011, a city ordinance changed the way permits were renewed, requiring that all business licenses be paid annually rather than staggered across the year (21). For small queer-owned establishments like Esta Noche, this shift proved devastating.

As a result, community members launched the “Save Esta Noche” campaign to help raise the necessary funds to keep the bar afloat (22). According to Bay Area Reporter journalist Peter Hernandez, Esta Noche faced a $9,000 bill just to keep its permits active, including a 20% penalty fee after a missed deadline (23). Legislative assistant Nate Allbee, who helped organize the fundraiser, explained that while the permitting reform was well-intentioned, it disproportionately hurt small venues already operating on the margins:

“Sometimes these bills can get lost in the mail, which can be tricky. [The ordinance is] all very well-meaning, but paying it all at once can be difficult for queer bars and organizations at the margins” (24).

The bar turned to the public for support. Fundraisers were launched, including an event hosted by local drag performers like Per Sia and Heklina (25). Even then, these efforts couldn’t match the financial burdens imposed by both policy and gentrification. Meanwhile, just a block away, upscale restaurants like Monk’s Kettle were packed nightly (26).

Supporters of Esta Noche pointed to gentrification as part of the issue between 2011 and 2012, sixteen new restaurants opened between 16th and 19th Streets, reshaping the neighborhood’s economic landscape (27). Despite community efforts, the owners couldn’t keep up. That spring, Esta Noche closed its doors (28). The loss hit hard. Esta Noche was one of the last spaces where queer Latine people in San Francisco could gather without fear. It had survived homophobia, racism, a public health crisis, and more only to fall to gentrification and municipal bureaucracy.

Today, the building is home to Mother Bar, a queer space for women and nonbinary people (29). While it’s good that the location continues to serve the LGBTQ+ community, it’s also a reminder of how rare it is to keep a space like Esta Noche alive over generations. Spaces like Esta Noche matter. They are not just clubs or bars. They are homes, classrooms, community centers, and more. These places became an avenue to building a future where queer and trans people of color are truly safe and valued.

Photo: © Rick Gerharter

Notes

1. OpenSFHistory, "The Early Years of SF Pride: A Closer Look," last modified June 28, 2020

2. Chris Carlsson, “The Castro: The Rise of a Gay Community,” FoundSF.org, 1995

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. Ricky Rodriguez, “Gay Latino Alliance: Latinidad and Homosexuality in the Mission District,” FoundSF.org, 2019.

7. Ibid.

8. Rachel, “Esta Noche Was the Epicenter of the Latine LGBTQ+ Community in San Francisco,” Nuestro Stories, June 7, 2022.

9. Ibid.

10. John Ferrannini, "Remembering Esta Noche as queer, POC spaces shutter," Bay Area Reporter, April 15, 2020.

11. Ibid.

12. Vivian Lopez, interview by Katrina Rodriguez, Transgender Oral History Project, Digital Transgender Archive.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.

16. Bay Area Reporter, "SAP Gives Out 500,000 Condoms," Bay Area Reporter, April 16, 1998.

17. Ibid.

18. Charles Orgbon III, "Adela Vázquez Didn’t Just Witness History—She Shaped It," San Francisco AIDS Foundation, December 6, 2024.

19. Ricky Rodriguez, “Gay Latino Alliance: Latinidad and Homosexuality in the Mission District,” FoundSF.org, 2019.

20. John Ferrannini, "Remembering Esta Noche as queer, POC spaces shutter," Bay Area Reporter, April 15, 2020.

21. Peter Hernandez, “Esta Noche Faces Fee Hurdle,” Bay Area Reporter, May 16–22, 2013, archival link

22. Ibid.

23. Ibid.

24. Ibid.

25. Ibid.

26. Ibid.

27. Ibid.

28. John Ferrannini, "Remembering Esta Noche as queer, POC spaces shutter," Bay Area Reporter, April 15, 2020.

29. Heather Cassell, "Mother's Day: New Women's Bar at the Former Esta Noche," Bay Area Reporter, April 11, 2023.