The Evolution of the San Francisco Bus Shelter

Historical Essay

by Eva Knowles, 2024

Bus shelter at 18th Street and Dolores.

Photo: Eva Knowles, 2024

| Having first become widespread in the 1980s, San Francisco’s bus shelters have played an important role in defining the landscape of the city. They are key elements in the city’s transportation network in addition to serving as both a medium for showcasing art and spreading awareness about social causes and a stage for debate over issues like homelessness and crime. |

When we picture the urban landscape, we may think of skyscrapers, parks, and other landmarks we can’t help but notice. Yet urban space is just as much defined by the structures we don’t pay attention to. The bus shelter is a clear example of this in the context of San Francisco, providing both protection from the elements and making the transit system more legible. The bus shelter is crucial to the fabric of the city, its streets, and the movement of people between them.

At the most lighthearted level, bus shelters have served as a stage for what has been branded a very San Francisco type of controversy. In 2006, the California Milk Processor Board involved the shelters in its “Got Milk?” campaign by plastering them with chocolate chip cookie-scented strips. In a city known for its environmental and health activism, this did not fly; the City was soon pressed to take down the advertisements amid concerns about chemicals and scent sensitivities (1). In 2008, the San Francisco Chronicle reported that strawberries were being grown on the roof of a bus shelter at Larkin and McAllister as part of an environmental initiative to grow more food locally. This, too, was met with criticism: “We may have had four shootings in the Mission last night, but at least we have strawberries growing on top of the bus shelter at Larkin and McAllister,” said a police officer interviewed for an article just two days later (2).

Many bus shelters across the city have had their glass panels removed.

Photo: Eva Knowles, 2024

The bus shelters also continue to inspire debate about crime and homelessness. In the early 2010s, multiple bus shelters were removed from the Tenderloin after complaints from neighborhood residents and law enforcement officials. They argued that the advertisements on the shelters blocked one’s view inside, therefore shielding criminal activity that occurs there: “The shelter is harboring criminals” (3). Many residents expressed a feeling of relief when shelters near their homes were removed; however, others, and particularly elderly people and disability advocates, argued that removing the bus shelters created a problem of access (4). In 2022, transit officials came up with an alternative to paying for expensive repairs for vandalized bus shelters. As part of the City’s contract renewal with Clear Channel Outdoor, which was extended through 2027, the company would permanently replace glass panels with metal bars at bus shelters in the Tenderloin, the Mission District, and on Market Street (5). Additionally, the company would increase bus shelter maintenance by 50%.

Bus stop at Eddy and Polk marked by a Muni sign atop a metal pole. In the Tenderloin, most bus stops look somewhat like this—lacking a bus shelter. Google Maps street view from 2022 shows a bus shelter in this spot, evidence that it was recently removed.

Photo: Eva Knowles, 2024

Crime and vandalism are not the only problem facing San Francisco bus shelters; another key issue is distribution of transit stops and the quality of their amenities for the people who use them. A 2022 study by Marcel Moran found that despite San Francisco’s “transit-first” policy directive, many stops lack seating, shelter, and adequate signage, and are often obstructed by street parking (6). Furthermore, stop amenities vary in a clear pattern across neighborhoods: stops in the northern half of the city and in census tracts with a higher percentage of white residents are more likely to feature seats, shelter, and unobstructed curbs, while the southern half of the city largely lacks these amenities. Bus shelters remain an issue of equity, as transit is made both less appealing and less safe to people without access to them.

Bus stops and shelters will also likely play a role in San Francisco’s Vision Zero effort as it continues to expand. The City has implemented a variety of safety improvements to transit infrastructure over the past decade, including a few projects at bus stops like bulb‑outs and bus bulbs, sidewalk widening in front of bus shelters, and bus stop relocation.

Bus shelter (center left) at Cesar Chavez and Potrero, 1946.

Photo: OpenSF History / wnp14.12499

By tracing the history of the bus shelter, we can come to understand how specific elements of its design provided the grounds for its eventual social significance. Bus shelters in San Francisco were scarce for most of the twentieth century. The first bus shelters in San Francisco looked more like small buildings, and existed in various locations around the city by 1940. Most bus stops, however, lacked not just a shelter but clear markings. There is evidence that marked poles were novel in the 1940s: in a 1943 letter to the editor, a Chronicle reader complained about the installation of steel bus stop signs and posts. While he appears most concerned with the material, the concept of bus stop signs also seems new to him: “We got along all these years without such steel posts” (7).

Woman boarding Muni bus at Haight and Divisadero, 1950. On the back of the photo: “PLEASE DON'T.. expect to board or alight except at regular stopping points.”

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Car and truck illegally parked in the bus stop zone on Sutter Street, 1950.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Even the bus stop zone was not a given by the late 1940s: “There is no uniformity regarding [the stopping of buses]. In some spots buses stop on the near side of cross streets, in others they move to the far side of the intersection. On some lines stops are made in an off-angle way at the curb line; in others patrons are forced to come to the center of the thoroughfare, as in the old-street car days, much to the annoyance of bus travelers and motorists as well,” wrote Leon J. Pinkson for the Chronicle in 1949 (8). People were still complaining decades later: one resident is quoted in a 1970 article as saying, “When I came to San Francisco, I was told the one place you could park for sure without getting a ticket was in a bus stop; that’s one thing that hasn’t changed” (9).

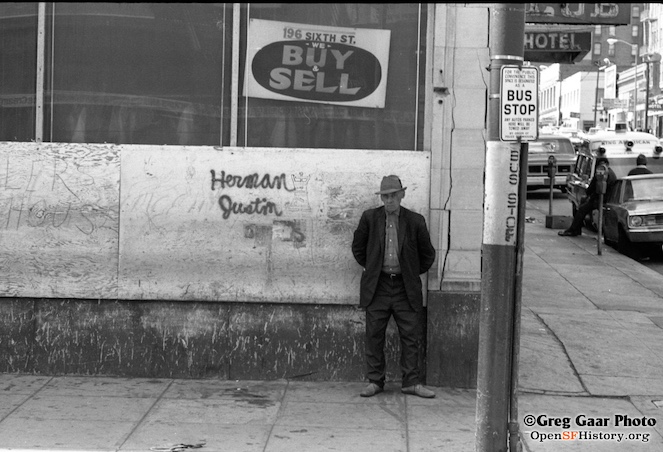

Bus stop with neither bench nor shelter at Howard and 6th, 1974.

Photo: Greg Gaar, courtesy of OpenSF History / wnp72.181

Predictably, these bus stops did not have much in the way of street furniture. Debate over benches can be traced back as early as 1950, when the Junior Chamber of Commerce issued a poll to Muni riders asking whether or not they wanted benches at bus stops (10). This remained an issue throughout the 1950s and 1960s. “We recently returned from the southern part of the State, where we observed that the bus service is about as bad as it is here, but hey try to make it more bearable for their patrons by supplying benches for them to sit on while waiting,” wrote a San Francisco resident to the Chronicle in 1958 (11). “Many of these people are old; some are mothers with children in their arms. Certainly benches should be supplied for them.” His plea garnered this response from the editor: “A spokesman for the Municipal Railway says that placing benches at bus stops and transfer points has been suggested many times and the management would like to oblige, but the Muni—being a deficit utility—just doesn’t have the funds” (12). Benches would not appear at bus stops until 1973, when the Finance Committee and Arts Commission approved a $50,000 proposal to install benches at 180 Muni stops (13).

It would take another decade for what we now recognize as a bus shelter—the advertising bus shelter—to become commonplace in San Francisco. The advertising bus shelter was invented in 1964 by Jean-Claude Decaux, who founded the outdoor advertising company JCDecaux. This design was appealing to city governments because bus shelters could finance themselves through advertising, and appealing to advertisers who were otherwise regulated in city centers. Decaux’s design would spread throughout Europe and metropolitan areas worldwide.

In February 1985, the Board of Supervisors approved a plan to install between 400 and 1000 bus shelters. The City would contract with a private advertising firm, who would construct and maintain the shelters in exchange for using them for advertising. The company would also pay the City $150,000 per year for fifteen years. San Francisco residents immediately pushed back against this plan, claiming that the new bus shelters would be an eyesore and attract crime. The City went forward with it, promising that no advertising would be permitted in residential areas and that the shelters would be well-lit and open to prevent criminal activity.

Bids for the $8 million contract were due in February 1986. One of the four bidders was JCDecaux, who offered to include free street toilets. Public Utility Commission general manager Rudy Nothenberg said that the toilets would disqualify JCDecaux if included and rejected the offer; the Berkeley-based Gannett Outdoor Co. was chosen instead. The results of this first bidding contest were thrown out at the recommendation of City Attorney George Agnost because of misleading City specifications, but in a second bidding contest in November of that year, the Gannett Outdoor Co. won once more.

Old Muni bus shelter, still in use in September 2015.

Photo: CBlount_Photography on Flickr

San Francisco’s advertising bus shelters have been imbued with political and social ideology from their beginning. The first of the bus shelters, on Van Ness Avenue near McAllister Street, was dedicated on October 16, 1987. In a San Francisco Chronicle article published the day after the ribbon-cutting, the shelters were described as “stylish, black-and-cream” as well as intentionally “bum-resistant [sic]” (14). They featured hard, narrow seats without backrests and which flipped vertically when unoccupied, thus discouraging people from sleeping there. Like other examples of hostile architecture in San Francisco and outside of it, this design choice had an adverse effect not only on the unhoused people it targeted but also on everyone else. The opening line of a 1988 article titled “Riders Have a Hard Wait at Muni Shelters” reads: “Plans to build 1000 modern bus shelters across San Francisco may be changed because of complaints that the narrow, flip-up seats for waiting passengers are a pain in the rear” (15). Plans, however, did not change; instead, Gannett installed descriptions of how to use the seats in various bus stops (16).

At the same time, the advertising space that the bus shelters provided were harnessed not only by megacorporations but also by artists and activists. Bus shelters publicized community events such as exhibits at San Francisco museums. In the late 1980s and 1990s, the shelters displayed AIDS awareness materials including photographs from “Art Against AIDS - On the Road” and were utilized along with newspapers and billboards for a $46,000 media educational campaign by the Department of Health directed at Black women vulnerable to AIDS. After a period of advertisements for alcohol, a group of young Mission District artists started the Fighting Back Bus Shelter Project, which created anti-alcohol abuse posters for bus shelters. The Community United Against Violence used bus shelters to raise awareness about anti-LGBTQ+ violence. These are just a few examples of many.

Through a series of purchases and absorptions throughout the late 1990s and early 2000s, Gannett’s Outdoor division became CBS Outdoor. The contract with the City carried over and was set to expire at the end of 2007, having been extended to 20 years. That May, bidding began for the new transit shelter contract. Each bidder—Cemusa, Clear Channel Outdoor, and CBS Outdoor and JCDecaux bidding as a pair—sent designs and prototypes to Muni, adding to 24 total schemes by various architects (17).

Designs proposed for San Francisco bus shelters, 2007.

Photos: Charles Bloszies (left) and SFMTA (center and right), courtesy of the San Francisco Municipal Transit Agency

In the end, Muni and the City selected Clear Channel Outdoor. The contract between the corporation and the City called for not only the installation and maintenance of over 1000 bus shelters, but also the construction of 3000 solar-powered signs at stops without shelters and technology to make taking the bus more accessible to visually impaired people. It also called for a massive gain in revenue for Muni; while CBS had been paying them 300,000 a year, the new proposal would guarantee them almost $7 million in the first year and over $25 million in the last year (18).

Winning design by Lundberg Design, 2007.

Photo: Ryan Hughes, courtesy of the San Francisco Municipal Transit Agency

It is the model put forward by Clear Channel Outdoor and designed by Lundberg Design that we see on the streets of San Francisco today. Lighting was engineered in line with the City’s energy efficiency standards; Radius Displays produced the LED light panels and solar roofs. The shelters were also largely composed of recycled materials, according to design company Monarch who worked on the project. The reddish-orange color of the roof was meant to evoke the Golden Gate Bridge; meanwhile, its wavy shape “[recalls] a seismic shock wave, a pattern of surf, a ribbon in the wind, even an abstraction of the curvy MUNI logo. The glass panels have a gradated frit pattern that resembles the fog in San Francisco – dense at the bottom and fading to clear at the top” (19). The bus shelters that we see today also adhere to much stricter guidelines than in the past. These guidelines regulate sidewalk widths, setbacks, and information displayed such as maps and real-time transit updates. Through this design, the bus shelter proved to not only improve the experience of taking public transit in San Francisco, but also came to symbolize the city itself in certain ways.

San Francisco bus shelters will continue to change as the city does. From their sparse beginnings in the 1940s to the contemporary designs that dot the cityscape, these structures have transitioned from mere functional elements to symbols of social significance, albeit often overlooked. As integral components of the city's transit system, they not only facilitate movement but also contribute to the broader dialogue on equity, safety, and public space, demonstrating the evolving priorities and values of San Francisco.

Notes

1. Gordon, Rachel. “Aromatic ads pulled from city bus shelters - Cookie smell didn't pass muster with the scent-sensitive.” San Francisco Chronicle, December 6, 2006.

2. Matier, Phillip, and Andrew Ross. “Arnold may face recall of his own.” San Francisco Chronicle, September 7, 2008.

3. Nevius, C.W. “A place for crime, with a cool chic design.” San Francisco Chronicle, July 25, 2013.

4. “Bus shelter policy crafted.” San Francisco Chronicle, January 17, 2012.

5. Cano, Ricardo. “No more glass panels on S.F. Muni bus shelters? This change could shift transit’s ‘losing battle’ against vandalism.” San Francisco Chronicle, October 5, 2022.

6. Moran, Marcel E. “Are Shelters in Place? Mapping the Distribution of Transit Amenities via a Bus-Stop Census of San Francisco.” Journal of Public Transportation 24 (2022): 100023.

7. Newton, William. “Posts” [Letter to the Editor]. San Francisco Chronicle, February 9, 1943.

8. Pinkson, Leon J. “Yelps Sounded on Muni Bus Stop Regulations.” San Francisco Chronicle, October 16, 1949.

9. Charrell, Lisa. “What’s Bugging Muni Drivers?” San Francisco Chronicle, September 20, 1970.

10. “Poll on Benches at Muni Stops.” San Francisco Chronicle, March 6, 1950.

11. “Bus Stop Benches” [Letter to the Editor]. San Francisco Chronicle, August 29, 1958.

12. Ibid.

13. “Muni Benches Plan Finally Gets OK.” San Francisco Chronicle, November 8, 1973.

14. Zane, Maitland. “1st ‘Bum-Resistant’ Bus Shelter - S.F., Gannett Unveil Muni ‘Flip Seats.’” San Francisco Chronicle, October 17, 1987.

15. Doyle, Jim. “Riders Have a Hard Wait at Muni Shelters.” San Francisco Chronicle, April 12, 1988.

16. Ibid.

17. King, John. “Want to design a bus shelter? Well, get in line.” San Francisco Chronicle, June 5, 2007.

18. “SFMTA Transit Shelter Advertising Agreement Approved by SF Board of Supervisors.” San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency Archives, 2007. San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. ; Gordon, Rachel. “Muni board OKs plan for Clear Channel to sell bus shelter ads.” San Francisco Chronicle, September 5, 2007.

19. “SFMTA Bus Shelters.” Lundberg Design, January 1, 2012.