Car-Free JFK Drive

Historical Essay

by Eva Knowles, 2024

JFK Drive during the Covid-19 pandemic, the eastern half open only to pedestrians, joggers, and bicyclists.

Photo: Chris Carlsson, May 2020

| The eastern half of John F. Kennedy Drive down the center of Golden Gate Park is closed to automobiles and turned over to an amazing multitude of people skating, biking, walking, running, and playing. An ongoing campaign to close large parts of the park to cars has intermittently made itself felt, but the city's Recreation and Parks Department resisted any permanent closure of JFK Drive until the COVID-19 pandemic. Even though there was well-funded opposition, San Franciscans voted in a large majority to permanently close JFK to cars in 2022. |

The transformation of John F. Kennedy Drive into a permanently car-free place of recreation is perhaps the clearest evidence of the COVID-19 pandemic’s effect on San Franciscans’ attitudes toward public space. Over the past century, few stretches of road have gotten as much attention as the 1.5-mile portion of JFK Drive between Kezar and Transverse Drives. Proposed closures of JFK Drive over the past sixty years have drawn the attention of coalitions of bicyclists and skaters; activists for the environment, transit, and people with disabilities; patrons of the arts; neighboring merchants; commuters; and really any San Franciscan who appreciates a walk in the park. Yet it took the advent of the pandemic to make permanent, full-time car-free JFK Drive a reality.

Bicycles were very widely enjoyed during the 1890's in Golden Gate Park and all of San Francisco.

Photo: Private Collection

A car-free portion of the road has existed on a temporary basis since 1967, when the San Francisco Recreation and Parks Commission initiated its first Sunday closure on April 2. That same day, the city changed the road’s name from Main Drive to John F. Kennedy Drive. Called the “People’s Day in the Park,” there was a small ceremony to mark the occasion. The San Francisco Board of Supervisors also unanimously commended the decision.

The closed portion of JFK Drive immediately attracted a variety of San Francisco residents, including bicyclists, skaters, pedestrians, joggers, and families with small children. It not only had the effect of bringing thousands of San Franciscans to the park, but it also opened the imaginations of some residents to a city less dependent on cars. Wrote San Francisco Chronicle sports columnist Ron Fimrite, “The car-free main drive—now John F. Kennedy drive—makes the park more of a park. It’s what it should be—a place to relax. Cycling along, zipping through the tunnels, gliding down foot paths, soaring over ‘No Bicycle’ markings, one is moved to thought. What, I thought, would downtown be like if there were no cars, just buses and cable cars? Heaven knows there’d be more room for people. And there’d be blessed quiet” (1).

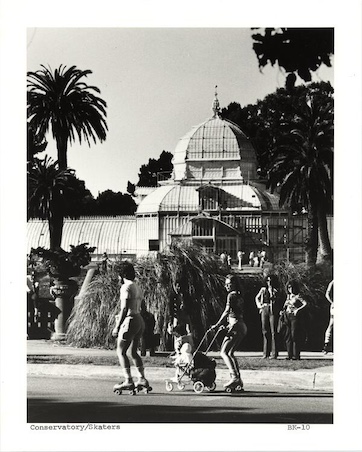

Skaters pass by the Conservatory of Flowers along JFK Drive. Written on the back of the photo: “On Sundays, when vehicular traffic is prohibited, the east end of San Francisco's 1,017-acre Golden Gate Park is a special haven for strollers, skaters and cyclists.” Likely from the late 1970s or early 1980s.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Before long, Golden Gate Park had attracted a community of skaters. One San Francisco Chronicle article described Sundays in Golden Gate Park as a “mad boom-box skate party” (2). According to staff writer David Rubien in 1990, “In Golden Gate Park on Sundays, when auto traffic is banned on John F. Kennedy Drive from Kezar Drive to 19th Avenue, thousands of knee- and wrist-padded roller skaters dance to rap music and disco or beeline down to the open road, dodging bicycles and baby carriages” (3).

In 1979, a few skaters formed a group that they called the Golden Gate Park Skate Patrol in response to the possibility of a ban on roller skating within the park. The group not only won that battle but took it upon themselves to act as guardians of the park, providing first aid and patrolling for trouble. In 1989, the park re-landscaped an asphalt area off JFK Drive at Sixth Avenue with smoother tar to accommodate skaters on weekdays when cars reappeared on the road. The construction of this area, called “the Skatin’ Place,” was largely due to the efforts of Skate Patrol and its head, David Miles Jr.

Sunday Skating on J.F.K. Drive in Golden Gate Park.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

By that point, the success of the Sunday closures had prompted city officials to consider expanding the program—a question that would continue to reappear at City Hall for decades to come. The first proposal was to extend the car closure to include Saturdays during the summer, and was brought to the Recreation and Park Department in 1971. This same idea was later proposed in 1992, shelved, and brought up once more in 1996.

It was at this time that the most prominent force standing in the way of car-free JFK Drive would make itself known. Higher-ups at the de Young Museum and Academy of Sciences claimed that visitors’ inability to drive would cut into their attendance. They argued that Sunday closure of JFK Drive had already made the museum and academy the only two museums in the country whose attendance dropped on Sundays. The de Young, in particular, had been struggling to repair the damage it suffered in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, and was faced with the question of its ability to finance a rebuilding project in Golden Gate Park. The alternative was to move out of the park to the Embarcadero—which the museum made sure to leverage. Not only was the proposal to close JFK Drive on Saturdays scratched from the Golden Gate Master Plan in 1997, but museum complaints spurred Supervisor Michael Yaki to propose reopening JFK Drive on Sundays to increase museum revenue.

Bicycle and pedestrian advocates brought their own threats—“If you thought the Critical Mass demonstration was explosive, it is a firecracker compared to the nuclear response that will be generated if the Sunday closure is changed,” said David Miles Jr., now a part of the “Free the Park” coalition (4). Eventually a compromise was reached: the de Young would stay in the park, and JFK Drive could keep its Sunday closures, if the museum was allowed to build an underground parking garage. San Francisco voters approved the proposal, yet the plan remained controversial, and by 2000, only about half of the $40 million of private funds needed to build the garage had been raised.

Car-free JFK Drive reappeared on the November 2000 ballot, and not only one time. A new group, Safe Golden Gate Park, had gathered eighteen thousand signatures hoping to—familiarly—close the stretch of road on Saturdays. This appeared as Proposition F, which ran into an obstacle when Supervisor Yaki put Proposition G on the ballot, which similarly called for Saturday closure—just not for at least five years, or until the Music Concourse underground garage was completed. Some people criticized Proposition G as an attempt to short-circuit Proposition F, while others rallied around it, arguing that time for test closures would prevent traffic, parking problems, and falling attendance at the park’s museums. Neither measure passed.

When Supervisor Matt Gonzalez and a majority of the Board of Supervisors proposed Saturday closures once more in August 2001, opponents took the issue to be one of democracy, not just recreation. Gonzalez, joined by a majority of the Board of Supervisors, advocated for an area less expansive than the one rejected in November 2000. However, opponents to the closure too found a new strategy, pointing to the Conservatory of Flowers, then in its second phase of rebuilding, as a potential victim of plummeting attendance, as well as the fact that there had already been multiple failed ballot measures. Chronicle writer Ken Garcia put it bluntly in February 2002: “It’s not exactly putting the cart before the horse. It’s destroying the cart and then putting the horse out to pasture… few municipalities can shatter common sense as dramatically as San Francisco, the slippery stone in the civic glass house” (5).

It took several more years for the pro-closure movement to make any real headway. In April 2006, the Board of Supervisors Land Use and Economic Development Committee approved a six-month-long test of Saturday closures, nicknamed “Healthy Saturdays.” During this period, city officials would collect data on the closure’s effects on traffic, parking, park usage, and the need for public transit. This plan notably included greater accessibility measures for the elderly and people with disabilities such as transit shuttles within the park on both Saturdays and Sundays. Though the Board approved the legislation, Mayor Gavin Newsom vetoed it on the grounds that it needed more study.

The Board tried again, and in April 2007 a compromise was reached with Mayor Newsom’s backing. JFK Drive would be closed on Saturdays for six months from just west of the concourse entrance to the de Young and the Academy to Transverse Drive—about half of the length of the road closed on Sundays. Criticisms from disability activists were addressed by the closure being contingent on compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, including wheelchair-accessible transit within the park, handicapped parking, and signage, as well as the city’s promise to improve other areas of the park. That November, a Board of Supervisors committee passed a measure extending the temporary ban on cars on Saturdays, April through September, for five years, and it was later extended again.

When COVID-19 pandemic lockdown began in March 2020, eyes turned back to JFK Drive as a place for socially-distanced escape. Walk San Francisco, an advocacy group, started an online petition to make JFK Drive car-free every day for the duration of the shelter-in-place directive. At the end of April, Mayor London Breed closed the 1.5-mile stretch in order to give people more space to get fresh air while still social distancing. Though Mayor Breed lifted the stay-at-home order in January of 2021, JFK Drive remained closed to cars. JFK Drive was not the only area garnering attention, but instead part of a movement to create safe public space throughout the city, including the Slow Streets program, the closure of the Great Highway, the expedited construction of bike lanes, and weekend evening street closures like on Valencia Street.

JFK Drive, crowded during the pandemic.

Photo: Chris Carlsson, May 2020

By April 2021, with the pandemic appearing to be subsiding, the car battle had ignited once more. Supervisors Shamann Walton and Asha Safai tweeted their support for JFK Drive’s reopening, and Walton published an editorial calling the closure elitist and segregationist and citing the testimonies of constituents who were unable to access the park.

However, this argument was quickly overshadowed: with an explosive increase in visitors to JFK Drive during its pandemic closure and a large amount of global praise, many city officials sought to make the closure permanent. In the fall of 2021, two San Francisco agencies, the Recreation and Parks Department and the Municipal Transportation Authority, began gathering public input in anticipation of a 2022 Board decision. The report, released in March 2022, backed permanent JFK Drive closure, citing both positive public feedback and data showing that the closure did not significantly affect traffic. In April, the Board of Supervisors met to vote on legislation proposed by Mayor London Breed that banned cars permanently. Over a hundred biking, walking, and safety advocates arrived on the steps of City Hall an hour before what would turn out to be a twelve-hour meeting, nine of those hours being public comment. The meeting ended in a 7-4 vote in favor of the closure. This move was again met with backlash from supporters of the de Young and the Academy as well as disability activists, but also with jubilation and a resurgence of public support. In the November 2022 election, the latter sentiment won out: a resounding 63% of voters were in favor of Proposition J, banning cars on JFK. Voters gathered along the road to celebrate in the days following.

Since the 2022 vote, the car-free stretch of JFK has been renamed JFK Promenade. A visitor to the Promenade will see runners, walkers, bicyclists, roller skaters, dancers and more pass by in great numbers. The Promenade’s street performers, sculptures, chalk art, lounge chairs, food trucks, seasonal light shows, lawn games, and even two pianos open to public players, are all courtesy of the Golden Mile Project, which preaches a “people-first” philosophy. SFMTA and San Francisco Recreation and Parks have installed accessibility upgrades including a free public shuttle. According to the latter city agency, there have been 12.6 million visits to JFK Drive since its April 2020 closure, making it the city’s most frequently visited open space.

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/natural-areas-golden-gate-park-sept-30-2023" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

After the visit to the Native Plant Nursery and a pause under the Monterey Cypresses at the east end of Golden Gate Park, the tour stops in the middle of a car-free JFK before entering the Oak Woodlands at the northeast corner of Golden Gate Park.

Video: Shaping San Francisco

Notes

1. Fimrite, Ron. “The Life Cycle.” San Francisco Chronicle. May 31, 1967.

2. Asimov, Nanette. “The Park’s Real Wheeler-Dealer.” San Francisco Chronicle. March 25, 1989.

3. Rubien, David. “Roller Revolution.” San Francisco Chronicle. January 29, 1990.

4. Wilson, Yumi. “Golden Gate Park Sunday Traffic Plan Irks Bikers, Skaters.” San Francisco Chronicle. August 7, 1997.

5. Garcia, Ken. “Don’t Nip Flower Power in the Bud.” San Francisco Chronicle. February 10, 2002.