Chinese as Medical Scapegoats, 1870-1905

Historical Essay

by Joan B. Trauner, California History Magazine, 1978

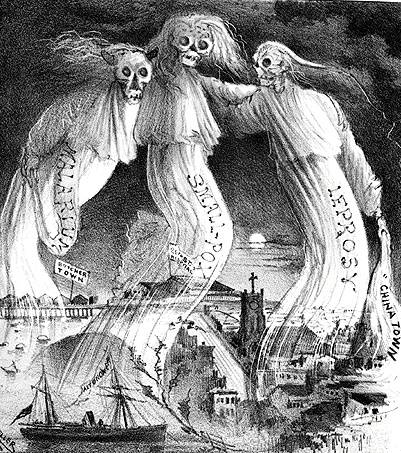

Cartoon from The Wasp of May 26, 1882, promoting the then-common racist myth that diseases were rampant in Chinatown.

| Hunters Point is the site of extensive pollution, home to hazardous materials and polluting plants. Over the course of decades, public officials have disappointed residents through their failure to effectively clean up Hunters Point. Particularly after mayoral candidate Matt Gonzalez lost the race in 2003, the community had to fight back against redevelopment and continued power plant operation. |

Much has been written about anti-Chinese sentiment on the West Coast during the 1870s and 1880s, especially the agitation to restrict Chinese immigration into the United States. Little has been said about anti-Chinese prejudice as reflected in the formulation of public health policy on the West Coast. Health policy, however, manifests not only the state of the medical sciences, but the expectations and the value system of society-at-large. In the era when health officials looked to sanitary reform as the primary means of preventing epidemic disease, the presence of an alien population living in substandard quarters was both socially and medically threatening.

By the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the Chinese were to become medical scapegoats; up and down the Pacific coast (and in the Hawaiian Islands) local health officials rationalized the failure of their sanitary programs by tracing all epidemic outbreaks to living conditions among the Chinese. This phenomenon was to last for over thirty-five years. Only after Chinese immigration was finally curtailed, following implementation of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 (and amendments of 1884), and only after scientific research began to unlock the mysteries of disease transmission did medical scapegoating begin to abate.[1]

The seeds for scapegoating in California first appeared in the 1860s. Whereas in the 1850s the early Chinese immigrants had been admired for their industry and frugality, by the 1860s the Chinese were considered to be "an inferior race" and a "degraded" people.[2] By the 1870s, the racist argument had broadened in scope, and the Chinese were viewed as "a social, moral and political curse to the community." Specific arguments advanced against the Chinese included:

1) the economic argument, as advocated by nativist and workingmen's groups, that cheap Chinese labor undermined wage rates and adversely affected employment practices on the West Coast;

2) the cultural argument, that the once enlightened Chinese civilization was corrupt and backward and that Chinese immigrants represented the lowest classes in China;[4]

3) the assimilationist argument, that the Chinese did not desire to merge into the American mainstream and, with their "abounding vices" (prostitution, gambling, opium-smoking), were impervious to the "loftier ideals" of Western civilization;[5]

4) the racist argument, that America should maintain a homogenous population and that national degeneration would ultimately result from permitting an inferior race (the Chinese) to mingle with a superior race (the Caucasian);[6]

5) the biological argument, that the Chinese were "inferior in organic structure, in vital force, and in the constitutional conditions of full development";[7] and, finally,

6) the medical argument, that the Chinese, ignoring all laws of hygiene and sanitation, bred and disseminated disease, thereby endangering the welfare of the state and of the nation.

Commenting in 1900 upon the dominant anti-Chinese mood of the late nineteenth century, Reverend Ira M. Condit, pastor of a Presbyterian Church mission in San Francisco's Chinatown since 1870, observed as follows:

There seems to be a combination of reasons which breed and keep alive this animosity against our Mongolian brothers. Race antagonism has undoubtedly something to do with it, but the fact that they do not assimilate with us has more. They constitute a foreign substance cast into our social order, which will not mingle, but keeps up a constant irritation. The amount of irritation depends upon the size of the disturbing mass. A few Chinamen would have no perceptible effect. They could be easily digested by the national stomach. . . But multiply units by millions, and the matter becomes exceedingly serious. Hence the fear of their pouring in upon us in overwhelming crowds has had much to do with our attitude toward them.[8]

In 1900 when Reverend Condit was writing about the Chinese, anti-Japanese sentiment had also made its appearance on the West Coast. However, because the high tide of Japanese immigration was to occur many years after that of the Chinese, a tradition of using the Japanese as medical scapegoats never developed. Advances in medical knowledge about the causation and transmission of epidemic disease had made any arguments along this line intellectually untenable. Instead, the Japanese were accused of having an excessively high birth rate, an argument never advanced against the Chinese. (The Japanese arrived in the United States as family units, or male immigrants imported "picture brides"; Chinese immigrants, on the other hand, were largely male laborers who left their wives or families behind in China.)[9] While the Japanese never became medical scapegoats, they were at times subject to discriminatory action, such as during the bubonic plague scare of 1900-1904.

This analysis will focus on the Chinese as medical scapegoats, dealing specifically with the situation as it existed in San Francisco from the year 1870, when the city's Board of Health was reorganized, to 1905, when public health officials concluded their five-year battle against bubonic plague in the Chinatown area.

By 1870, San Francisco had the largest concentration of Chinese in California--24.4 percent of the state's Chinese population.[10] Although they comprised five percent of the total population of San Francisco, only a token number were admitted into the health facilities operated by the city and county.[11] In 1870, the primary municipal facilities were the Almshouse, built in 1867 and located on eighty acres near Lake Honda (site of the present Laguna Honda Home), and City Hospital, built in 1854 and located on Francisco and Stockton streets. Chinese patients were shunted off to a smallpox (or "pest") hospital or to a special building, originally operated exclusively for the Chinese and later designated as the Lazaretto or Lepers' Quarters. Both of these facilities were located at Twenty-Sixth and Army streets, near the site of the future City and County Hospital (opened in 1872).

In 1870, the San Francisco Board of Health was reorganized as a distinct political unit with considerable power within the city. Composed of the mayor and four physicians appointed by the governor of California, the board supervised the administration of the city hospitals, the jail, the correctional school (the industrial school), and the quarantine system for the harbor. It also appointed a city health officer (also a physician) who was to oversee health and sanitary conditions within San Francisco.[12] While these physicians were theoretically chosen from among the best trained members of the profession, the range of municipal problems with which they were confronted was often beyond the scope of their medical expertise. Thus, the pronouncements of the board and the health officer were often characterized by political or social expedience, rather than by scientific insight. Beginning in the 1870s, they were to credit Chinatown with introducing and disseminating every epidemic outbreak to hit San Francisco. In the words of one astute physician writing in 1876: "The Chinese were the focus of Caucasian animosities, and they were made responsible for mishaps in general. A destructive earthquake would probably be charged to their account."[13]

The line of attack used by health officers against the Chinese was directly related to the medical theories of the period. According to the miasmatic theory of disease popular in the 1870s, epidemic outbreaks were caused either by the state of the atmosphere or by poor sanitary conditions affecting the local atmosphere. Chinatown, with its "foul and disgusting vapors," was regarded as the primary source of atmospheric pollution within the city. Numerous citations were issued by the health authorities for such sanitary offenses as "generating unwholesome odors," improper disposal of garbage, faulty construction of privy vaults and drains, and failure to clean market stalls.[14] When a virulent smallpox epidemic struck San Francisco in 1875-76, the city health officer ordered every house in Chinatown to be thoroughly fumigated. Nevertheless, the epidemic raged on, resulting in some 1,646 reported cases with 405 deaths among the white population of San Francisco.[15] Unable to account for the severity of the epidemic, the city health officer, J. L. Meares, offered the following explanation:

"I unhesitatingly declare my belief that the cause is the presence in our midst of 30,000 (as a class) of unscrupulous, lying and treacherous Chinamen, who have disregarded our sanitary laws, concealed and are concealing their cases of smallpox."[16]

To the sanitarians of the 1870s, Chinatown was more than a slum. It was "a laboratory of infection," peopled by "lying and treacherous" aliens who had minimal regard for the health of the American people. The general acceptance of the germ theory in the 1880s did little to dispel the popular belief that epidemic outbreaks were directly attributable to conditions within Chinatown. As before, medical theorization was inseparably linked with social attitudes and prejudices.

The "germ" theory of disease is now an acknowledged fact in the science of medicine... This theory teaches us that material like cloth, tobacco, food, if exposed to the atmosphere charged with those germs, is infected by them, and thus detrimental to the health of the wearer or consumer of such merchandise. The dangerous result of such evil, we hold, is practically proven by the ravages of diseases like diphtheria, etc., in this city, irrespective of time, season or places. The physician who tries to trace the source of the infection is mostly always unable to do so, and we believe that the existing evils in Chinatown are the proper source.[17]

By 1880 criticism of conditions in Chinatown had become so widespread that the Board of Health, responding to political pressure, issued a resolution formally condemning Chinatown as a "nuisance."

The Chinese cancer must be cut out of the heart of our city, root and branch, if we have any regard for its future sanitary welfare . . . with all the vacant and health territory around this city, it is a shame that the very centre be surrendered and abandoned to this health-defying and law-defying population. We, therefore, recommend that the portion of the city here described be condemned as a nuisance; and we call upon the proper authorities to take the necessary steps for its abatement without delay.[18]

Proposals to quarter the Chinese outside of the city limits of San Francisco were advanced at this time, primarily under the sponsorship of the Anti-Chinese Council of the Workingmen's party. Similar proposals had been set forth since the 1850s and would recur again in the 1800s and at the time of the bubonic plague crisis in the early 1900s.[19] However, no formal condemnation proceedings were ever instituted, and Chinatown remained located in the center of San Francisco. This central location brought the Chinese into daily contact with the Caucasian population of the city and was a constant source of irritation to many San Franciscans. To one city health officer, Chinatown was "the moral purgatory" through which all who pass come out nauseated and disgusted, and perchance defiled by Mongolian filth or disease.[20]

Sanitarians and politicians were especially concerned about the large number of so-called "courtesans" who operated in the Chinatown area. These prostitutes were believed to be infected with a particularly virulent form of syphilis that was almost impossible to cure. Testifying before the congressional committee investigating conditions in Chinatown in 1877, Dr. H. H. Toland (founder of the Toland Medical College, subsequently the University of California Medical School) reported that nine-tenths of the venereal disease in San Francisco could be traced back directly to Chinese prostitutes. Since it was believed that most of the Chinese houses of prostitution were patronized primarily by whites, Chinese prostitution was seen as "the source of the most terrible pollution of the blood of the younger and rising generations." In his testimony, Dr. Toland stated unequivocally that he had never heard or read of any country in the world where there were so many syphilitic young men as in San Francisco.[21]

An equal source of consternation to the medical community—and to the general public—was the presence of lepers in the Chinatown area. Apparently, by 1875 a number of lepers of particularly "loathsome appearance" had drifted to San Francisco from throughout the state. While some sought treatment at the Twenty Sixth Street Lazaretto, the majority were presumed to be hidden in the "subterranean dens" of Chinatown. During the 1870s and early 1880s, little was known about the etiology of leprosy. It was presumed to be hereditary, contagious, incurable, more common in the male than female, and likely to disappear with hygienic improvement.[22] To one city health officer, leprosy among the Chinese was "simply the result of generations of syphilis, transmitted from one generation to another."[23] Another view held that leprosy was inherent in the Chinese and infused into the Caucasian race by the smoking of opium pipes previously handled by Chinese lepers. As early as 1871, the Chinese were accused of introducing "the dread scourge" of Mongolian leprosy to the West Coast. In 1876, an amendment to the general police law of California made it unlawful for persons afflicted with leprosy to live in ordinary intercourse with the population of the state and provided that such persons "be compelled to inhabit lazarettos or lepers' quarters."[25] In 1878 and again in 1883, health authorities descended on Chinatown, ferreted out the lepers, and placed them in the Twenty Sixth Street Lazaretto with the intention of sending all Mongolian lepers back to China at the first opportunity. Of the 128 lepers admitted to the Lazaretto from July, 1871, to April, 1890, 115 were classified as "Mongolians" and 83 of the total number were ultimately shipped back to China.[26]

Except for cases of leprosy, deportation on medical grounds was not a common procedure during the nineteenth century. Rather, immigration officials attempted to prevent the entry into this country of persons suspected of carrying contagious disease. Regulations for reporting infectious disease on incoming vessels had existed since the 1850s. By 1870, shipmasters entering San Francisco harbor were required to report to the quarantine official of San Francisco all cases of Asiatic cholera, smallpox, yellow fever, typhus, and "ship fever."[27] Increasingly, the fear was expressed that the Chinese in particular were carriers of alien disease that would cause the physiological decay of the American nation.[28] In May, 1873, the San Francisco Board of Health passed a resolution whereby all vessels arriving from China were required to come to anchor in the Bay and all passengers were to be subjected to a personal examination by the quarantine officer.[29]

Generally, quarantine of incoming passengers was laxly enforced during the 1870s. However, with the acceptance of the germ theory in the 1880s, efforts were intensified to prevent the importation of foreign germs into this country. A regulation of the San Francisco Board of Health, dated June, 1884, specified that all vessels arriving from Asiatic ports must be detained for inspection, fumigation, and disinfection.[30] Another measure, dated July 1884, specified the method of inspection to be used for all vessels arriving from Asian ports.

The Quarantine Officer and his assistants shall make an examination of every part of the vessel into which they can enter ... Two or more inspectors shall, after all the Chinese steerage passengers have been brought on the upper deck, commence at the extreme rear portion of each deck ... and proceeding forward, examine every compartment, stateroom, storeroom ... driving all Chinese steerage passengers they may find on the upper deck. When the inspection of the vessel is completed, the Quarantine Officer shall come on deck, and, with the aid of his assistants, shall count the Chinese passengers, men; women and children separately. The white passengers and crew must be mustered and counted first.[31]

Until the 1890s, quarantine of incoming vessels was generally a state function. The National Quarantine Act of 1873 had empowered the surgeon general of the United States Marine Hospital Service to enforce port quarantine only if he did not interfere with the laws and procedures of the states involved.[32] However, with the passage of the quarantine law of February 15, 1893, the United States Marine Hospital Service was given direct responsibility for administration of port quarantine. (With the implementation of this law came a series of jurisdictional disputes between the quarantine officer of San Francisco and officers of the Marine Hospital Service. These disputes, which lasted into the early years of the twentieth century, often hampered the effective administration of quarantine procedures.) In 1894, bubonic plague was reported in Canton and Hong Kong, and within a short spell of time, the disease spread throughout the Port cities of the Far East. In 1896, the San Francisco Board of Health declared the ports of Yokohama, Kobe, Shanghai, and Hong Kong to be "infected" with bubonic plague. Under the board's ruling of December 16, 1896, all Chinese and Japanese passengers, together with their baggage and portable effects, were to be remanded to the city's quarantine station.[33] Simultaneously, the Southern Pacific Railroad ceased selling tickets to Asiatics.

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/ssfCHNTALY" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

1900 Health Inspection

Notes

1. In the 1880's, bacteriologists began to isolate the micro organisms responsible for some of the most feared diseases known to man. Important dates of discovery include: typhoid fever, 1880; tuberculosis, 1882; cholera, 1883; diphtheria, 1883; tetanus, 1884; and bubonic plague, 1894.

2. U.S. Congress, Senate, Reports of the Immigration Commission, Senate Doc. 633, 61 Congress, 2 Session, 1911, XXXIX, p. 68.

3· San Francisco Board of Supervisors, Municipal Reports (1876-1877), p. 397.

4.·U.S. Congress, House, Chinese Immigration, Misc. Doc. 9, 45 Cong., I Sess., 1877, pp 16-17.

5· Ira M. Condit, The Chinaman as We See Him (Chicago: Fleming H. Revell Co., 1900), p. 36.

6. Arthur B. Stout, "Impurity Of Race, as a Cause of Decay," First Biennial Report of the State Board of Health of California for the Years 1870 and 1871 (D. W. Gelwicks, 1871), p. 71.

7· Thomas M. Logan, M.D., "The Chinese and the Social Evil Question," First Biennial Report of the State Board of Health, 1871, p. 48.

8. Condit, The Chinaman as We See Him, 21.

9. R. D. McKenzie, Oriental Exclusion: The Effect of American Immigration Laws, Regulations, and Judicial Decisions Upon the Chinese and Japanese on the American Pacific Coast (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1928), p. 31.

10. Thomas W. Chinn, ed., A History of the Chinese in California: A Syllabus (San Francisco: Chinese Historical Society of America, 1969), p. 23.

11 Ibid.

12. J. Marion Read and Mary E. Mathes, History of the San Francisco Medical Society: 1850-1900 (San Francisco: San Francisco Medical Society, 1958), 1:57.

13. Pacific Medical and Surgical Journal, 19 (June, 1876), 36-37.

14. [Workingmen's Party of California, Anti-Chinese Council], Chinatown Declared a Nuisance! (San Francisco, 1880), p. 5.

15. Municipal Reports, 1877, p. 394.

16. Ibid., 397.

17. Chinatown Declared A Nuisance, 13.

18. Ibid., 6.

19. Gunther Barth, Bitter Strength. A History of the Chinese in the United States, 1850-1870 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1964), p. 151.

20. "Report of Special Committee on the Condition of the Chinese Quarter," Municipal Reports, 1885, p. 208.

21. U.S. Congress, House, Chinese Immigration, Misc. Doc. 9, 45 Cong., I Sess., 1877, pp 13-14.

22. "Mongolian Leprosy," Municipal Reports, 1885, p. 247.

23· Examination of the testimony of John L. Meares, M.D., on Oct. 24, 1876 before Joint Special Committee to Investigate Chinese Immigration, Report of the Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration: Report and Evidence (Ottawa: Order of the Royal Commission, 1885), p. 198.

24. Chinatown Declared A Nuisance, 12.

25. "Mongolian Leprosy," 234-235.

26. H. S. Orme, M.D., "Leprosy, Its Extent and Control, Origin and Geographical Distribution," Transactions of the Medical Society of the State of California, XX (1890): 170.

27. "Mongolian Leprosy," 235.

28. Stout, "Impurity of Race, as a Cause of Decay," 71.

29. Report of the Quarantine Officer of the Port of San Francisco (San Francisco: James H. Barry, 1897), p. 15.

30. San Francisco, General Orders of the Board of Supervisors Providing Regulations for the Government of the City and County of San Francisco, 1898, p. 478. Hereafter cited as San Francisco Ordinances.

31. Ibid., 478-479.

32. Rosebud T. Solis-Cohen, "The Exclusion of Aliens from the United States for Physical Defects," Bulletin of the History of Medicine, XXI (1947): 41.

33. San Francisco Ordinances, 1898, p. 495.