Livermore Action Group Adopts New Strategy, Fall 1983

Primary Source

by Barbara Haber, originally published in It’s About Times, the newspaper of the Abalone Alliance, October-November 1983, p. 13.

| The Livermore Action Group (LAG) was an anti-nuclear group who organized civil disobedience in the early 1980s. In September 1983, the LAG adopted the Campaign Proposal in an effort to broaden public support. Members perceived that the LAG placed so much of a focus on civil disobedience that it excluded people who weren’t prepared for that. The Campaign Proposal aimed to help the group fully utilize its radical political potential by including more people. |

Three months, one Congress, and one Regional Council after its June 1983 blockade, the Livermore Action Group has adopted a proposal that may significantly change the way it operates. First introduced in August at LAG's annual Congress, the so- called Campaign Proposal calls for major shifts in LAG's activities and decision-making process. The proposal proved so controversial that after a full day of debate, it was tabled until the Regional Council meeting a month later. There, it was finally adopted with modifications at the end of another long day of discussion.

What is this political hot potato that has provoked so much debate? The Campaign Proposal calls for a shift from an "action-to-action" approach to one in which a short-range goal (several months to a year) is strategically adopted, and a variety of activities and actions are undertaken to fulfill that goal. It calls for a more integrated and diversified approach to planning, in which civil disobedience is supplemented by legal demonstrations, community organizing, outreach and education, undertaken where appropriate in coalition with other groups.

This shift toward strategic planning and diversified tactics implies several changes within LAG. First, it requires political discussion about the merits of various action proposals. Second, it modifies LAG's self-definition: while still focused on civil disobedience, LAG will allocate more of its resources to organizing and education. Affinity groups are asked to take on increased organizing tasks, including those not directly tied to civil disobedience. Work groups are asked to aid affinity groups by providing internal education, skills workshops, and organizing materials.

Lawrence Ferlinghetti (center, white beard) and Daniel Ellsberg (on knees in foreground) at a protest in front of the Lawrence Livermore Labs, May 5, 1983.

Photo: Jackson Nichols

LAG has accomplished it great deal in its two and a half years. It has choreographed massive acts of civil disobedience, created a network of over 2000 activists and 200 affinity groups, maintained a uniquely decentralized structure and consensus process, and provided a common political identity for politically diverse people.

Those of us who drafted the Campaign Proposal were motivated by frustration with what we saw as self-defeating limitations LAG had placed on itself, and by a sense of greater opportunity growing out of increased public receptivity to LAG.

But there have been shortcomings too. First, LAG has not been able to broaden its social base. Its members remain predominantly white, a coalition of (a few) functionally upper middle class people, (many) middle class and (fewer) working class dropouts. Nor has LAG increased in actual size. There were 20% fewer participants in the June Blockade at Livermore than there had been the year before. And the number of people doing most of the organizing for LAG actions has remained small.

A growing number of people see this stagnation as an inevitable outcome of LAG's total emphasis on civil disobedience. As a sole focus, civil disobedience excludes many people who might otherwise be attracted to LAG's radical politics.

If LAG is going to attract and keep people with jobs and families, it must provide a variety of political tasks that bring with them full membership and status in the LAG community. It must give up any hint of a two-tiered structure in which those who can do the most civil disobedience are heroes, and those who can't are seen as less committed. The diversification of activities suggested in the Campaign Proposal addresses the structural root of LAG's narrow social base and offers a concrete program for change.

A second political weakness in LAG is the failure to develop political and organizational skills among participants in its actions. While committing civil disobedience can be profoundly radicalizing, it doesn't provide enough political skill and. experience enough to build a long term, functioning political organization, capable of enduring over the long haul. While it is true that many affinity groups do political organizing on their own, many do not, and few take responsibility for bringing into being the major LAG actions to which they consense.

As a result, thirty or forty people wind up as an elite that does much of the organizational work, creating resentment between work groups and affinity groups. While some in LAG see the problem as too much power vested in the work groups, the drafters of the Campaign Proposal see the problem as one of too little participation in organizing by the vast network of affinity groups. By bringing affinity groups into LAG's political and organizational processes, we hope to create an organization that is both more democratic and more productive.

Personal empowerment as well as organizational productivity need strengthening in LAG. Without day-to-day experience in political debate and organizational process, affinity group members remain mystified by the inner workings of the organization. In addition, the focus on participating by putting our bodies on the line inadvertently replicates certain limitations that have long been imposed on women. The drafters of the proposal want LAG to provide a training ground where people, especially women, can overcome socially enforced and psychologically internalized inhibitions about speaking, arguing, writing, and deciding.

A third political weakness in LAG has been its failure to utilize fully its radical political analysis. Although LAG handbooks spell out a political perspective distinct from that of other peace groups, and although most active LAG members share a sophisticated, anti-imperialist understanding of the roots of the arms race, LAG does not give priority to articulating its politics publicly, or to political discussion within LAG.

Many of us value LAG not only because it organizes civil disobedience, but for its radical analysis of the arms race and militarism, one that includes both Marxist and feminist insights without indulging in ideological dogma and glib formulas for social change. Yet some of us see the combination of political radicalism and militant activism as what is most potentially powerful in LAG, and most essential in building the kind of peace movement that could make a difference.

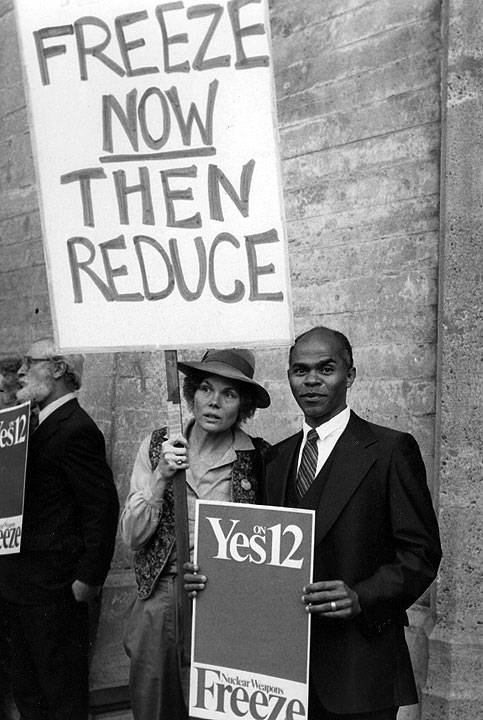

In 1982, an enormous amount of energy went into passing the Nuclear Freeze initiative in California.

Photo: It's About Times

The single-issue, legislative focus of the Freeze has led the peace movement toward a dead end. Now, with the 1984 elections approaching, many peace, left and progressive groups are climbing aboard the Democratic Party bandwagon. While there are differences within LAG about the Freeze and electoral politics, it has always recognized the limitations of establishment politics and understood the systemic nature of US military and nuclear policies. It is essential that LAG join in the political debate now heating up within the peace movement over strategy and tactics in an election year.

Among the fears expressed about the Campaign Proposal is the possibility that diversification will lessen LAG's commitment to civil disobedience. Although it is possible that taking on new kinds of political work will take energy from civil disobedience in the short run, in the long run diversification and fuller participation by affinity groups will create a larger community of skilled organizers, capable of mounting many more actions, legal and illegal, than LAG can now undertake. More important, the political impact of each act of civil disobedience will be greatly enhanced by the context created through LAG's organizing efforts.

Perhaps the deepest fear aroused by the Campaign Proposal is the fear of loss of community. LAG has brought together a miraculously diverse group of people and has managed, to create a political and social space in which it is possible to feel whole and human while working for social change. LAG's focus on shared physical opposition to the state, and on developing a process that takes feelings into account has solidified our sense of commonality.

Although we have avoided the specter of factionalism, we have done so at the expense of substantive debate over politics and strategy. The danger of political splits is real, though the common will to keep the community together is a strong force against excessive divisiveness. But there is danger to the LAG community from another direction, one less frequently articulated: that those who seek change within the organization will be weeded out or marginalized. In its understandable desire not to rock its communal boat, LAG runs the risk of losing its dynamic tensions, of becoming a community held together by warmth and moral righteousness but lacking in political texture, in which group experience itself becomes the end to which all other ends are subordinated. This too has been a traditional fate of political groups.

The Campaign Proposal is a conscious act of rocking the boat. We've chosen to risk the dissonance of political encounter rather than the slow erosion that takes place when political encounter is evaded. We've chosen to struggle rather than join the ranks of the disappeared that LAG has already accumulated. Our belief is that the communal boat is solid enough to hold together. By honoring our commonalities without denying our differences we hope to participate in forging an organization and a movement that is both tough and loving.

Barbara Haber is one of the drafters of the Campaign Proposal.