The Duel

Historical Essay

by K. Maldetto

Broderick-Terry duel site in 1996; the posts mark where the two men are said to have stood.

Site of Broderick-Terry duel in 1996

Photos: Dimitri Loukakos

Dueling was common in California and San Francisco in the 1850s and, while illegal, it was generally considered a proper way to settle disputes. On September 13, 1859, however, a most uncommon duel, of historical consequences, occurred between two men named David C. Broderick and David S. Terry. These were representative men, occupying positions of power in the Democratic party and carving out places for themselves in the history of the young republic of California. David C. Broderick, former president of the California Senate, leader of the anti-Lecompton (i.e. anti-slavery) wing of the California Democratic party, was one of the two United States Senators from California. David S. Terry was a California Supreme Court Justice and one of the leaders of the dominant wing of the California Democratic Party, the pro-slavery "Chivalry" as it was known.

These were very trying and tense times for the Nation divided as it was on the issue of the extension of slavery and its politicians failing to maintain a balance of force between "free" and "slave" states. In California, slavery had been outlawed by the constitution but the Democratic Party, mostly dominated by the pro-slavery Chivalry, controlled the state in spite of the rising power of the new anti-slavery Republican Party. William Gwin, US Senator from California and leader of the Chivalry, was personal friends with President Buchanan, whose sympathies lied with the southerners, and hence controlled all federal patronage and most of the Democratic machine in the state. In Senator Broderick, however, the Chivalrists found a master politician (who despite being in the minority managed to get elected to the US Senate by exploiting internal differences within the Chivalry) and a fierce opponent to slavery and the exploitation of the working class by the powerful. Broderick was the life and soul of the anti-Lecompton wing of the Democratic Party and the Chivalrists and friends of the Buchanan Administration held a deep hatred for him. If only Broderick were "out of the way," the Chivalry could reunite the Democratic Party and be sure to sweep the state in the elections of 1859. The campaign of 1859 would prove to be one of the most vehemently fought ones in California history with major candidates insulting, degrading and even challenging one another to duels during speeches!

The immediate cause of the Broderick-Terry duel was a speech delivered by Judge Terry at the Lecompton Democratic State Convention held in Sacramento in 1859. In his speech he derided the anti-Lecompton Democrats as "a miserable remnant of a faction flying under false colors." Far from being independent men fighting against slavery they were:

…the personal followers of one man, the personal chattels of a single individual whom they are ashamed of. They belong heart and soul, body and breeches, to Senator David S. Broderick. They are yet ashamed to acknowledge their masters, and are calling themselves, forsooth, Douglas Democrats.... Perhaps they do sail under the flag of Douglas, but it is the banner of the black Douglas whose name is Frederick not Stephen.

Terry was referring to the fact that the anti-Lecomptonites were not behind Stephen Douglas, a prominent and respected US Democratic Senator opposed to slavery, but rather Frederick Douglas, the black abolitionist. Terry's speech was acclaimed by the delegates but he did not win a new nomination to the California Supreme Court.

On June 26, Broderick read Terry's speech while at breakfast at the International Hotel in San Francisco. He was in the company of a number of people including a friend of Terry's named D.W. Perley. He was furious and could not help but venting his anger. He threw the paper in front of Perley and said to him: "I see your friend Terry has been abusing me at Sacramento." Perley asked him to explain what he meant and Broderick, no longer able to control himself, unleashed:

The damned miserable wretch, after being kicked out of the convention, went down there and made a speech abusing me. I have defended him at times when all others deserted him. I paid and supported three newspapers to defend him during the Vigilance Committee days and this is all the gratitude I get from the damned miserable wretch for the favors* I have conferred on him.

Broderick was writhing with anger, his fists were clenched and the veins in his forehead were swelling from the fury. By then, the guests at the table knew that something unusual and heavy with consequences was happening but before anybody could interject, Broderick lashed out again: "I have hitherto spoken of him as an honest man—as the only honest man on the bench of a miserably corrupt court—but now I find I was mistaken. I take it all back. He's just as bad as the others."

Realizing that he could not remain silent, Perley told Broderick he would inform Terry to which the Senator responded with characteristic aplomb: "Do so; I wish you to do so: I am responsible for it." Perley did quickly inform Terry who, after the conclusion of the elections, wrote a letter of inquiry to Broderick. The senator replied by restating verbatim part of what he said at the International Hotel and by not offering a retraction. The Senator's letter**, given that it offered no retraction, left Terry no choice but to issue a formal challenge for a duel which he did the very same day. The next day Broderick wrote a missive in response accepting*** the challenge. At this point the seconds were chosen and the date for the duel was fixed for September 12th.

Everyone in San Francisco knew about the duel and newspapers wrote about it as if this event were long expected. Broderick was generally thought to have the advantage as he was a better marksman. The San Francisco Morning Call reported thus:

It is generally understood that Judge Terry is a first-rate shot, but is doubtful whether he is as unerring with the pistol as Senator Broderick. This gentleman, recently, in practicing in a gallery, fired two hundred shots at the usual distance, and plumped the mark every time. As he is also a man of firmer nerve than his opponent, we may look this morning for unpleasant news.

In fact, the duel did not occur that morning. As dueling was illegal and this one was so publicized, the authorities had to intervene. Broderick and Terry were arrested at the site of the duel, a mile or so east of Lake Merced, and released the same day. The two men, however, were determined to have it out and the duel was called for the very next day at the same site.

The next morning the Senator and Judge were both present at the same site. This time, despite a sizable crowd of 80 people and the presence of the press, the sheriffs were nowhere in sight. As the seconds prepared the details of the duel, Broderick paced about in the sand and Terry discussed a few last issues with his personal surgeon. According to witnesses, both of the duelists seemed calm and weren't showing any fear or anxiety.

Broderick won the coin toss for position and placed himself with his back to the sun which was just now piercing through the thick morning fog. Terry got to choose the pistols and, of course, opted for his own, a set of French dueling pistols with which he had been practicing for several months now. The seconds examined and loaded the pistols and then handed them over to the duelists. The men were then searched by the seconds to ensure that they did not carry any objects that might deflect a bullet.

The Senator and Judge were now called to their positions. David Colton, one of Broderick's seconds, was in charge of initiating the duel. "Gentlemen," exclaimed Mr. Colton in a clear voice, "are you ready?" "Ready," answered Terry almost immediately, his voice thick with tension. Everyone in the crowd was now looking at the Senator. Why was he not answering? Apparently, his right arm was tense, his hand fidgety and he couldn't get a good grip on the pistol. After a few seconds, which seemed like an eternity to all, Broderick nodded and said "Ready." Colton called out in a measured voice: "Fire." "One." "Two."

Broderick fired first to the call of "One." He had aligned his arm strait along his target but the pistol discharged before he was able to bring it level with Terry. The bullet headed dead-on towards Terry but buried itself in the ground only nine feet away from Broderick. Everyone was surprised given the Senator's marksmanship. Just as Colton made the final call of "Two," Terry fired and hit the right part of Broderick's chest. A tear could be seen in his coat but the wound did not seem serious at first. After a few seconds, though, Broderick winced and extended both his arms out as if to catch his balance. Then his body shook and his pistol fell out of his hand. The Senator was hard hit. After a few seconds, Broderick could no longer control his movements and his body was overtaken by a violent tremor. He turned to the left, his head now drooping. His left knee gave away, then his right. After a last desperate effort to keep himself up with his left arm, he fell prone to the ground his face looking up towards the sky. A thin rivulet of blood came out from his mouth as he said apologetically to his mates that he had tried to rise but "the blood blinded me." The mighty Senator had finally met his match.

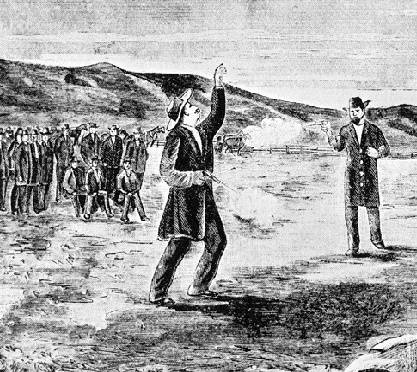

Contemporary historic cartoon of the Broderick-Terry duel.

Image: Bancroft Library, Berkeley, CA

In the meantime, Terry stood watching convinced that he had not wounded the Senator very seriously. Broderick's surgeon and his seconds were trying to determine the gravity of the wound. As little blood came out from the mouth, the wound was not judged to be dangerous. The Senator was then carried on to a wagon and brought to the house of his friend Leonidas Haskell. During the trip, Broderick complained of acute pain to the chest. His seconds repeated to him that the wound would likely heal. In fact, however, despite the absence of blood from his mouth, the wound proved to be very serious. Terry's bullet had hit the Senator's right lung. Soon after arriving at Haskell's house, it became clear that the Senator did not have long to live. After three days of agonizing, Senator Broderick died in the morning of September the 16th.

Broderick's death was deplored throughout the city. His remains were laid in an open casket and brought to the Union Hotel, at the corner of Kearny and Merchant Streets, on Portsmouth Square. Large groups of mourners filed past his casket during the morning of Sunday the 18th. The funeral for Senator Broderick was held that afternoon at Portsmouth Square and was the largest ever held in San Francisco's history. The crowd, which overflowed the square, was estimated at over 25,000 people.

At precisely 1:30, a funeral procession, consisting of seven mounted horsemen and behind them a crowd of mourners, brought the casket from the Hotel to the center of Portsmouth Square where a podium was erected. When the casket was placed on a bier besides the podium, Edward Baker, a close friend of Broderick and Abraham Lincoln, came to the podium and delivered a brilliant funeral oration. Much of the speech, as would be expected, was a eulogy of the Senator but, in truth, when examining the record, Baker's praise was not wholly undeserved: "Who can speak for masses of men with a passionate love for the classes from whence he sprung? Who can defy the blandishments of power, the insolence of office, the corruption of administrations? What hopes are buried with him in the grave?" Baker, a consummate orator, proceeded to praise Broderick by contrasting him with the Chivalrists: "Consider his public acts--weigh his private character--and before the grave encloses him forever, judge between him and his enemies!" Baker then extended his argument and brought it to its natural conclusion. In fact, Baker proceeded, Broderick had been killed for his political convictions: "His death was a political necessity poorly veiled beneath the guise of a private quarrel."

Broderick's political career, in any event, was over given the Chivalrists smashing victory in the recent state elections. With the Chivalrists controlling state patronage and offices, and the rising Republican Party stealing the abolitionist wind from the anti-Lecomptonite sails, Broderick's political base was annihilated. Then came the duel with Terry. Ironically, the only thing that could save or "resurrect" Broderick and again transform his ideas into a political force that could not be crushed was...his death.

In fact, Broderick's death led to a reversal in California politics. Citizens, outraged at Broderick's death, which was now commonly referred to as an assassination, began to turn away from the Chivalrists. In California, there was less and less sympathy for the Southerners who were generally thought to be threatening the Union. This change in mood was very clearly exemplified when US Senator Gwin left California to return to Washington for a new session of Congress. Given that Senator Gwin had led his party to a resounding victory in the last elections, one would have expected a great crowd and celebration to see him off. Well, there was a crowd, all right, and they did want to see him off, definitively off. From the deck of the steamer, Senator Gwin could see a group of citizens but they were quiet and the mood was far from celebratory. They held a large sign which read: "The will of the people--may the murderers of David C. Broderick never return to California." A year and a half later, with the outbreak of the Civil War, Gwin, as well as Terry, did indeed leave California to join the Confederacy. In 1860, under the guidance of Baker who persistently exploited Broderick's death for political gain, the Republicans carried California in the presidential elections and in 1861 they won the state elections. In the end, Broderick's influence and ideas, skillfully extolled by the Republicans, and combined with a powerful alliance between Western bankers and Northern industrialists put an end to the power of the Chivalry in California.

- Broderick Saves Terry 1856: Broderick was referring to events during the Second Committee of Vigilance in August 1856. At that time, Terry was arrested for stabbing a vigilante named S.A. Hopkins in an attempt to free one of his friends from imprisonment by the Vigilance Committee. Hopkins was severely wounded to the neck and had he died, Terry would have likely hung. It took the exertion of much influence, to a great extent on the part of Broderick, to get Terry freed.

- Broderick's Response to Terry:

SENATOR BRODERICK'S RESPONSE TO TERRY'S INQUIRY

Friday Evening, September 9, 1859

Hon. D.S. Terry:

Yours of this date has been received. The remarks made by me were occasioned by certain offensive allusions of yours concerning me, made in the convention at Sacramento, and reported in the Union of the 25th of June. Upon the topic alluded to in your note of this date, my language, so far as my recollection serves me, was as follows: 'During Judge Terry's incarceration by the Vigilance Committee I paid two hundred dollars a week to support a newspaper in his (your) defence. I have also stated heretofore that I considered him (Judge Terry) the only honest man on the Supreme bench. But I take it all back.' You are the proper judge as to whether this language affords good ground for offence.

I remain, etc.

D.C. Broderick

- Why Broderick accepted: It is likely that the victory of the Chivalry in the elections of 1859, during the summer, made Broderick feel very disillusioned about his political future and made him more careless about his fate and the gravity of the act he was about to engage in. Indeed, the victory of the Chivalry, and the rising power of the Republican Party, in these last elections essentially meant the end of his anti-Lecompton wing and arguably of his political career. The Senator perhaps felt like he had nothing to lose anymore by engaging in this duel.

Further reading:

Ellison, Joseph; A Self-governing Dominion: California 1849-60; Berkeley, 1950.

Jackson, Joseph H.; The Western Gate, A San Francisco Reader; Farrar, Strauss and Young, 1952.

Quinn, Arthur; The Rivals, William Gwin, David Broderick and the Birth of California; Crown Publishers, 1994.

Royce, Josiah; California: A Study of American Character; Boston, 1886.

Starr, Kevin; Americans and the California Dream; New York, 1973.

William, David A.; David C. Broderick, A political Portrait; Kingsport Press, 1969.