Diane di Prima, Beat Generation Poet

Historical Essay

by Nancy Snyder, originally published at the Literary Ladies Guide, August, 2022.

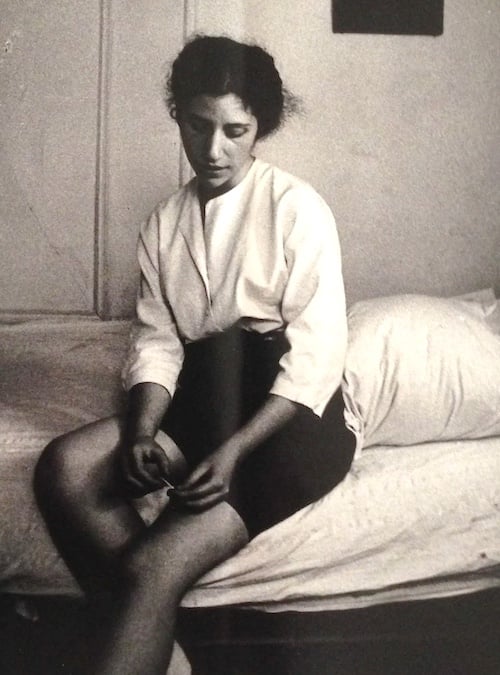

Diane di Prima

Photo: Estate of Diane di Prima

The extraordinary feminist and Beat generation poet Diane di Prima (August 6, 1934– October 5, 2020) was an active participant in the cultural and political movements of the last half of the twentieth century. She embodied the awareness of a poet’s sensibility required for these political fights to evolve.

Di Prima wrote the poem following when she was named as the San Francisco Poet Laureate in 2009. In eight seemingly simple lines, she brings the credo of her life’s visionary work:

- my vow is:

- to remind us all

- to celebrate

- there is no time

- desperate

- no season

- that is not

- a Season of Song

- (from “First Draft: Poet Laureate Oath of Office,” 2009)

On October 25, 2020, in her beloved adopted hometown of San Francisco, di Prima passed away with her husband, family, and friends at her bedside. She was eighty-six years old and had been in assisted living for the past two years.

Despite her physical struggles, di Prima continued to write every day and had several book projects in the works. It would be hard to accept that her gritty and tough poetic voice would now be silent—with her heart in every word, after creating fifty books and chapbooks of poetry over nearly sixty years.

Childhood and formative years

Diane Rose di Prima was born on August 6, 1934 in Brooklyn, New York. She grew up in the Italian-American neighborhood of Carrol Gardens, the oldest child of Frank di Prima, a lawyer, and his wife Emma, a schoolteacher.

In Di Prima’s 2003 memoir, Recollections of My Life as a Woman, the reader notices the dominant influence of her maternal grandparents, Domenico and Antoinette Mazzolli. Domenico was an anarchist and an Italian immigrant who worked as a tailor; his friends and colleagues included fellow anarchists Emma Goldman and Carlo Tresca.

- Today is your

- birthday and I have tried

- writing these things before,

- but now

- in the gathering madness, I want to

- thank you

- for telling me what to expect

- for pulling

- no punches, back there in that scrubbed Bronx parlor.

- (from “April Fool Birthday Poem for Grandpa”)

Di Prima remembers back to the time when she was three to four years old and her grandfather, Domenico, shared a secret from the family: they would spend long hours listening to Italian opera—a treat that was forbidden to Domenico. Italian opera, with its sorrows and its vicissitudes of its heroes and heroines, had his doctors warning him that his bad heart may give out from the emotional strain of the opera.

Domenico was a popular anarchist speaker; di Prima remembered one of those speeches, when “the arts shine down on us, the leaves glow in the electric lights of the park. I am proud of him, and afraid, but mostly amazed. His words have awakened my full acknowledgment, consent, I hear what he says as truth, and I seem to have always known it.”

Di Prima’s grandmother, Antoinette, shared a grand passion with Domenico but also imparted sound advice to the young Diane that yes, men may be considered special, but women can survive without them.

“My Grandmother’s Catholicism was of the distinctive Mediterranean variety: tolerant and full of humor. ‘Eh!’ my Grandmother would say, ‘The Virgin Mary is a woman, she’ll explain it to God.’ It indicated on one hand, the Virgin Mary knew much better than God the ins and outs human nature, what we were up to, and that she had a tolerance and intelligence and humor that was perhaps missing from the male godhead.”

It was a comfortable home; di Prima went to the Parochial school in her neighborhood and helped her younger brothers with their homework. When it came time for her to choose a high school, she took the exam for the prestigious Hunter College High School in Manhattan and broke the record for the highest score on the written test.

Di Prima and a group of seven other students (including the brilliant poet Audre Lorde) had formed a poetry circle: young women sharing their work and dedicating themselves to the art of the written word. At fifteen years old, di Prima made her commitment to her life’s destiny known: she would spend her life being a poet.

“Seeing a life of striving, possibility of living within a vision … I know I will be a poet, and knowing that knowing what I will lose. Keats said it: I am certain of nothing, but the holiness of the Heart’s Affections and the Truth of the Imagination,” she wrote of her revelation during adolescence. She drew on the strength of her maternal grandparents’ political anarchist ideals and their passion for art, decided to risk everything and write.

Diane di Prima in 1959.

Photo: James Oliver Mitchell

The Greenwich Village years

When it came time to consider college, di Prima entered a New York City competition for excellence in Latin and earned a scholarship to the prestigious Swarthmore University. Di Prima had decided to study physics, but after three semesters, she dropped out and became an integral part of the Greenwich Village literary scene that dominated the late 1950s and 1960s.

Di Prima rented a flat for thirty-three dollars a month and became friends with Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Frank O’Hara, and Denise Levertov. She became a co-founder of the Poets Press and the New York Poets Theatre and co-editor of the literary magazine The Floating Bear.

“She was important as the feminist voice of the Beat generation,” said Lawrence Ferlinghetti, co-founder of San Francisco’s City Lights Bookstore. Di Prima wrote about “the equality of the sexes,” fellow poet and close friend Amber Tamblyn wrote in The New Yorker, “She saw herself as a weapon to be deployed—no, detonated—against her oppressors. She wrote about women as wolves, women as predators, as hunters, as villains. She wrote about fat women, queer women, androgynous women, disobedient women, women as Gods, as birds, as the wind.”

- I have just realized that the stakes are myself

- I have no other ransom money, nothing to break or barter but my life

- my spirit measured out, in bits, spread over

- the roulette table, I recoup what I can

- (from “Revolutionary Letter #1”)

San Francisco

In 1968, di Prima packed up her four children and settled in San Francisco. This time she settled into a fourteen-room flat on the corner of Laguna and Page. The location was at the epicenter of the cultural and political awakenings happening in San Francisco in the 1960s and early 1970s.

Di Prima was an active participant in the movements against the Vietnam War, and the fight for civil, labor, immigrant, and LGBTQ rights. As with her writing, Di Prima’s activism never waned.

- The value of an individual life a credo they taught us

- to instill fear, and inaction, ‘you only live once’

- a fog on our eyes, we are

- endless as the sea, not separate, we die

- a million times a day, we are born

- a million times, each breath life and death:

- get up. put on your shoes, get

- started, someone will finish.

- (from “Revolutionary Letter #3”)

Although di Prima had chosen Greenwich Village instead of an academic path, she landed several jobs as a college instructor at The San Francisco Art Institute and the California College of the Arts.

For many years, she would load her children into the family’s truck to teach at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poets with fellow Beats Allen Ginsberg, Anne Waldman, William Burroughs, and Gregory Corso.

- Sweetheart

- when you break thru

- you’ll find

- a poet here

- not quite what one would choose.

- I won’t promise

- you’ll never go hungry

- that you won’t be sad

- on this gutted

- breaking

- globe

- but I can show you

- baby

- enough to love

- to break your heart

- forever

- (from “Song for Baby-O, Unborn”)

Diane di Prima’s Legacy

Di Prima’s life was unconventional by conventional standards: light-years removed from the standards of conformity that choked one’s creativity and authenticity. “So much of the woman I am today is because of the woman Diane once was,” Amber Tamblyn remembered.

One of di Prima’s most seminal works is Loba, first published in 1978 as an open-ended poem and as the feminist answer to Allen Ginsberg’s Howl. In 1998, twenty years after its debut, Loba was published again in a more expansive eight-part poem and she finally considered the work complete.

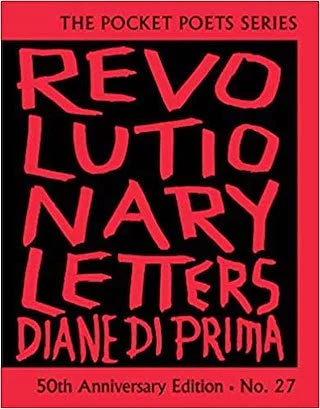

The same creative process happened with Revolutionary Letters. First begun in the 1960s, with portions being published for the next few decades, until 2014 when di Prima completed the book.

In an interview given three years before her death, di Prima spoke of her legacy to her readers as “giving them the courage to change their lives. People get caught in the conventions of society and they forget what they are really after.”

- I’d like my daily bread however

- you arrange it, and I’d also like

- to be bread, or sustenance for

- some others even after I’ve left.

- (from “The Poetry Deal,” 1993)

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/_wXMrfej18Q?si=iH9lqwudCNXBYx3o" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Diane di Prima was incredibly prolific, with numerous published collections of her work. See an extensive bibliography here.