Little Italy in Early 20th Century

Historical Essay

by William Issel and Robert Cherny

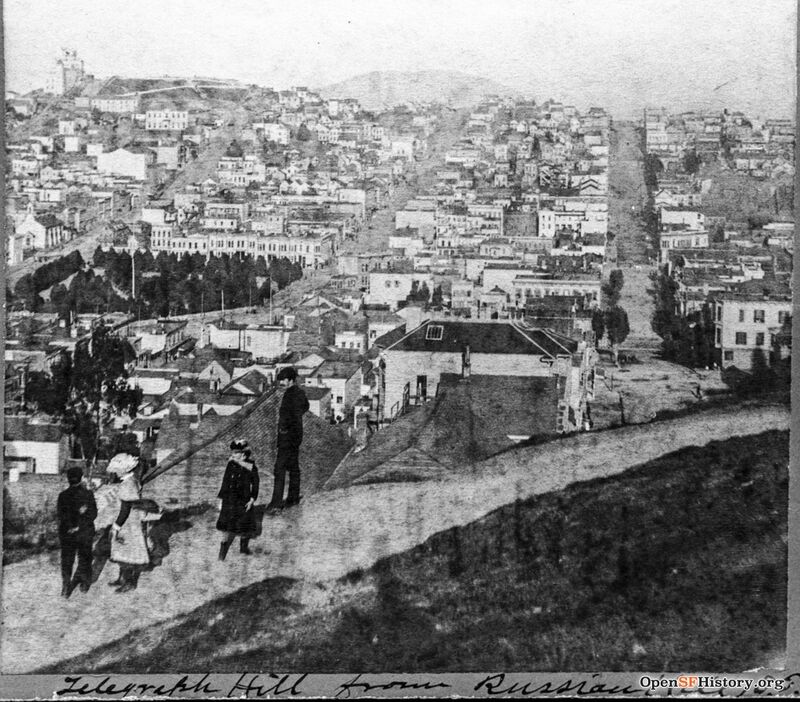

View east from Russian Hill over North Beach, c. 1890.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp37.00922

In 1900, Dupont Street was the center of Chinatown from California to Broadway. Across Broadway, however, the language of Dupont Street was not Cantonese but Italian. North Beach—named for a beach long since vanished as the waterfront had been moved northward by landfills—was the center of San Francisco’s Italian community, a predominantly working-class community but one that also included businessmen and professionals. Initially the area at the base of Telegraph Hill had been known as the Latin Quarter and had included French, Italian, Mexican, Spanish, and Portuguese residents, living “in low houses, which they transformed by balconies into a semblance of Spain.” Then, the Italians were to be found on the slopes of Telegraph Hill.

Their shanties [formerly home to Irish waterfront workers] clung to the side of the hill or hung on the very edge of the precipice overlooking the bay, on the verge of which a wall kept their babies from falling. ... It was more like Italy than anything in the Italian quarter of New York and Chicago.

Eventually the Italian settlement overflowed Telegraph Hill and inundated North Beach, making the area near Montgomery Avenue (renamed Columbus Avenue in 1910) and Broadway a “Little Italy,” filled with Italian stores shops, theaters, restaurants, churches, and social organizations.(41)

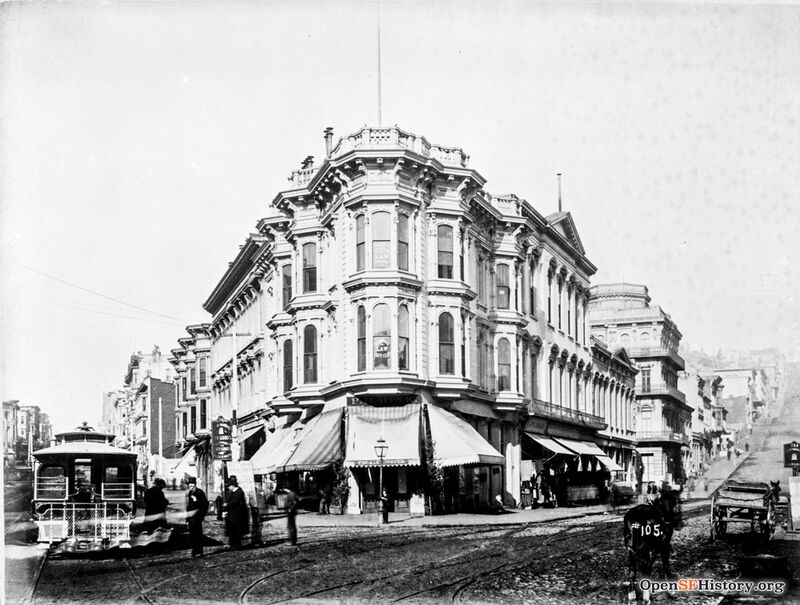

Montgomery Avenue (later Columbus) and Montgomery Street, 1880s.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp26.335

By 1910, 30 percent of all the residents of the area bounded on the south by Broadway and on the west by Jones had been born in Italy, and fewer than 20 percent of the adults’ parents had been born in the United States. Two-thirds of the population was male, and population densities were well above the citywide average. By 1910, the area bounded by Jones and Broadway had an average of eight people per dwelling. In the early twentieth century, two other Italian neighborhoods developed, one in the Outer Mission District, near the southern boundary of the city and the truck farms of the peninsula, and a smaller one on Potrero Hill. These outlying Italian settlements, however, were more scattered and never developed into rivals of North Beach as the centers of Italian economic and cultural life.(42)

Although there were factories in North Beach, for example, the Ghirardelli chocolate factory and Domenico di Domenconinis Golden Grain macaroni factory, most Italians were not to be found in factory work. By 1900, four occupations had become distinctively Italian, accounting for nearly 22 percent of all Italian males in the work force: hucksters and peddlers, 28 percent of whom were Italian; agricultural laborers, 34 percent Italian; fishermen and oystermen, 51 percent; and bootblacks, 90 percent. Italians were largely unrepresented in white-collar occupations, among merchants and dealers (except as fruit and vegetable sellers), and in the construction and metal trades. Only among laborers did the proportion of Italians exceed their proportion of the total work force, and only 6 percent of the city’s laborers were Italian.(43)

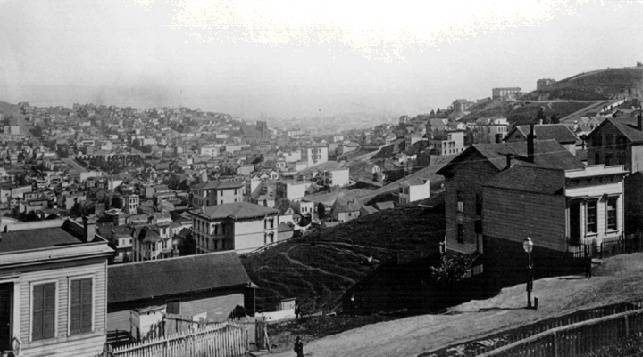

Looking southeast across North Beach from Russian Hill c. 1885. (Washington Square Park is visible in left center). Nob Hill rises to upper right, today's financial district is the low point in center.

Private Collection, San Francisco, CA

Fisherman's Wharf, c. 1891, when it was still off the northeast corner of Telegraph Hill.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org

To a major extent, the economic life of North Beach was dominated by fishermen and truck farmers. Feluccas with orange-brown lateen sails plied the bay, and larger boats moved out through the Golden Gate to do deep-sea fishing. The Filbert Street wharf, known as Italy harbor, was the center of the fish trade until 1900 when Fisherman’s Wharf was built on its present site near the foot of Columbus. There the boats unloaded the day’s catch, and street peddlers (both Chinese and Italian) bargained with fishermen. By 1900 the fishermen were largely Sicilians, and the truck farmers and agricultural laborers were predominantly Ligurians. Commission merchants tended to be Genovese, and the street peddlers, for both fish and produce, were largely Lucchesi, from Tuscany. Truck farms were located throughout the Outer Mission District, beyond the areas built up in housing, and down the peninsula south of the city. Most farmers were either tenants or employees, but a few owned their own tracts. In the early twentieth century, increasingly, Italians began to dominate some aspects of food processing, notably pasta making, wine making (especially in areas to the north of San Francisco, but to some extent within the city), cheese making, and the canning of fruit, vegetables, and fish.(44)

The Bank of Italy was unquestionably the most successful of the North Beach enterprises. Founded in 1904 by Amadeo Peter Giannini, a successful produce merchant, the bank broke with precedent by catering not to the most successful entrepreneurs (several other Italian banks did that), but instead to the small businesses and working people of North Beach. When the earthquake struck in 1906, the bank was still so small that Giannini could load all the cash reserves ($80,000), records, and most of the office furniture onto two wagons and save them from the fire. Five days after the fire had burned itself out and while the great fireproof vaults of the major banks were still too hot to be opened, the Bank of Italy resumed business, financing reconstruction of North Beach and other parts of the city as well. In 1907, Giannini opened a branch in the Mission District, and mergers soon added branches in San Jose (1909), Los Angeles (1913), and elsewhere in the state. Giannini acquired banking interests in New York and Italy as well. By 1927, the Bank of Italy was the third largest bank in the nation, but only the largest of several Giannini-run banking chains. Two years later, most of the Giannini banks in California merged to become the Bank of America.(45)

Notes

41. The descriptions are by Will Irwin, The City That Was: A Requiem of Old San Francisco (New York, 1906), pp. 45–46. See also his description of the bay filled with orange-brown lateen sails, p. 19. Deanna Paoli Gumina, The Italians of San Francisco, 1850–1930 (New York, 1978), pp. 18, 20–33. esp. p. 25.

42. Table 104, “Population, Dwellings, and Families, for Places Having 2,500 Inhabitants or More: 1900,” Twelfth Census of the United States: 1900, vol. 2, pt. 2, p. 640; Table 23, “Population by Sex, General Nativity, and Color, for Places Having 2,500 Inhabitants or More: 1900,” ibid., p. 610; Table 5, “Composition and Characteristics of the Population for Wards (or Assembly Districts) of Cities of 50,000 or More,” Thirteenth Census of the United States: Abstract of the Census with Supplement for California, p. 616. For 1900, North Beach was a part of assembly districts 44 and 45, dividing it along Kearny Street and including a good deal of Downtown in the 45th. Much of the 44th was also not Italian. For 1910, the 45th District included all of North Beach and some small surrounding areas. See Dino Cinel, From Italy to San Francisco: The Immigrant Experience (Stanford, 1982), esp. chs. 5–7.

43. Table 43, “Total Males and Females 10 Years of Age and over Engaged in Selected Groups of Occupations, Classified by General Nativity, Color, Conjugal Conditions, Months Unemployed, Age Periods, and Parentage, for Cities Having 50,000 Inhabitants or More: 1900,” Twelfth Census of the United States: 1900, 20: 720–724; Gumina, Italians of San Francisco, ch. 4.

44. Gumina, Italians of San Francisco, ch. 4, and also pp. 33–37.

45. Julian Dana, A. P. Giannini: Giant in the West (New York, 1947); James and James, Biography of a Bank.

Excerpted from San Francisco 1865-1932, Chapter 3 “Life and Work”