Looking Back at the Frisco Bay Mussel Group

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson, 2023

The Frisco Bay Mussel Group was a “committee of correspondence” focused on sharing regional identity and watershed consciousness. From its founding in 1975 to its demise in 1978, it rejected the common dichotomy between city and country, declaring that they were essentially interrelated through, and encompassed by, the San Francisco Bay-Sacramento River Estuary watershed. They knew that urban priorities dominated regional politics and economics, which shaped then (as it does now) the sense of “the Bay Area,” so they set out to redefine that sense of regionhood for all the inhabitants of this expansive watershed. Breaking from the common boundaries of ecology and conservation environmentalism of the era, they sought to learn about and integrate a comprehensive understanding of history, biology, economics, ecological restoration, geology and climate, and the full range of life forms that existed historically and persisted into the present in the rivers, the delta, the bay, and the ocean, and all the lands defined by those waters. Rejecting a pedestal putting humans above other forms of life, they argued for a multi-species approach to ensure biotic richness and diversity—which would benefit human beings too!

The Frisco Bay Mussel Group had its first meeting in October 1975 at The Farm at Potrero and Cesar Chavez Streets (then Army Street). The first call to meet was addressed to “Self-Declared Interdependent Members” who were in the SF Bay region. From the outset, the goal was to promote the notion of “inhabitance” as popular policy, with localized contributions from each participant meant to embody a vision of “inhabitory government.” Dozens of people responded to the call and began to attend regular meetings at The Farm in a collective endeavor to explore where they were. Different people would spend time researching and presenting on different topics, whether a local waterway, alternative energy or nuclear power, urban farming/gardening, etc. As material began to congeal over the first year or two, the idea emerged to condense it into a booklet, eventually appearing as “Living Here” in 1977.

As the main notetaker at most of the meetings, Eric Noble transcribed in impressionistic and sometimes literal ways the ruminations of the folks who helped shape a regional ecological sensibility that far exceeded the bounds of their own efforts. Ultimately, dozens of today’s projects, campaigns, history books, and frames of reference were impacted, shaped, or inspired by the collective efforts of this loosely associated but surprisingly influential group in the mid-1970s.

Early SF Mime Troupe show poster

Eric Noble is also the archivist of The Diggers, a San Francisco phenomenon that emerged in the wake of the Hunters Point Rebellion and ensuing martial law at the end of September 1966. Some of The Diggers had been part of the early SF Mime Troupe and performed in the edgy anarchistic commedia dell’arte plays staged for free in public parks—leading to their arrests as, on cue, the cops showed up and began taking performers away.

Digger Poster from 1966

Image: Digger Archive

By late 1966, several actors left the Mime Troupe and, joined by others, produced the infamous “1% Free” wall poster that appeared in the Haight-Ashbury (and around San Francisco) in October 1966. “Street sheet” handouts began to circulate in large numbers and soon, a prodigious effort to glean and gather food made possible free public feedings every afternoon in the Panhandle. This was soon augmented by the establishment of “free stores,” ongoing free concerts in the Panhandle and beyond, and a steady stream of interventions in public life. Peter Berg and Judy Goldhaft were in the epicenter of this whirlwind, along with dozens of others, but the history of The San Francisco Diggers is a different story.

In 1973, Peter Berg founded the Planet Drum Foundation, and it was from their rich milieu of thinkers and supporters, including a number of their erstwhile Digger co-conspirators, that they convened the Frisco Bay Mussel Group in late 1975. Noble describes his memory of the group dynamics:

The main “mover and shaker” of FBMG was Peter Berg, of course. Emmett Grogan aptly named Peter the Hun in [his novel of The Diggers] Ringolevio “because he was his own horde” and any group with Berg was like one of those Buddhist mandalas with concentric circles of divine beings surrounding the enlightened One in the center.

Peter was certainly a charismatic and brilliant man but it’s notable how many others brought their own formidable experiences to the group, and how many made lasting contributions both near and far. For example, Peter Warshall presented a slideshow at the 2nd meeting on October 29, 1975 documenting the destruction of native habitat around the Bay. Warshall was already by then an accomplished biologist and anthropologist, having studied under both Frederic Jameson and Claude Levi-Strauss. More importantly, he helped launch the widespread effort to save wildlife that became Bird Rescue after the 1971 oil spill under the Golden Gate Bridge. He died at age 70 in 2013, remembered in an elegant obituary in Conservation Biology as a Biogladiator, a man who “was preaching sustainability before the word was defined.” He served as Mayor of Bolinas, and was well known for having designed its septic recycling system built on the Mesa north of the village. Carrying the FBMG/Planet Drum credo throughout his life, he felt strongly about sense of place: … “two things can perhaps save the world. One would be the mastery of one’s kindness to oneself… and the other would be understanding your passion for place—for where you live—and really loving the place that you live in.”

Linn Freeman House was another regular participant, an original Digger too, and a person who later moved to the far north of California with his partner Nina Blasenheim.There they established themselves as founders and key members of the Mattole Salmon Group and the Mattole Restoration Council in 1983. Taking the concepts developed in the Frisco Bay Mussel Group, Freeman encouraged both upriver and downriver dwellers on the Mattole to see themselves as “reinhabitors,” who were placed on the river for a higher purpose. Ali Freedlund’s obituary of House describes him as a “watershed mystic—one who seeks, by contemplation and self-surrender, unity with the watershed… By the time he joined us here in the Mattole… to help build the watershed restoration idea into one of the central social movements of our times, his relationship to his fellows was typified by a quiet dignity and an exceptional conscientiousness.”

Peter Coyote was a regular and important participant in the Diggers and the Frisco Bay Mussel Group, appearing often in the documented discussions of the latter. He is of course famous as an actor who appears in over 100 films and TV shows, but most of us are most familiar with him through his voice as the narrator on Ken Burns's documentary series on the National Parks, the Roosevelts, and Country Music, among many other achievements (he also pops up as a voice on a lot of commercials). Bob Carroll, a famous performance artist, took one of Freeman’s essays on salmon that he’d presented to the FBMG and turned it into a surrealistic enactment of a dancing-singing salmon somehow caught up in the scandals then plaguing the singing group The Supremes. He gave this performance at the conclusion of a meeting in 1976 and it was talked about forever after.

I cannot do justice to all the interesting people who passed through the meetings of the Frisco Bay Mussel Group, and left their own important stamp on its short blazing trip through Bay Area history. Chip Lord was a co-founder of the infamous Ant Farm art & architecture collective (best known for their row of buried Cadillacs in a Texas field). Rasa Gustaitis wrote Wholly Round about the environmental activism of the 1960s and early 1970s, attended Frisco Bay Mussel Group meetings, and eventually became the editor of Coast & Ocean magazine from 1986-2005, a publication dedicated to protecting the California coast from rampant exploitation.

David Schooley, now in his 80s, has been the indefatigable defender of San Bruno Mountain since the late 1960s, and brought his unique sense of the mountain and its vibrant history to the FBMG. He also hosted a couple of Frisco Bay Mussel Group gatherings in San Bruno Mountain’s Buckeye Canyon on the shellmound which provided a deeply historic site for ribald revelry.

Watershed Interdependance, Nov. 20, 1977, San Bruno Mountain

Marc Kasky helped build the San Francisco Ecology Center on Columbus into a dynamic meeting space for dozens of groups and individuals in the 1970s before he went on to be the director of Fort Mason and turn it into a path-breaking example of “reinhabiting” abandoned military facilities. Bob Callahan, a poet, writer, teacher, publisher, and editor, founded Turtle Island Books which gave a literary home to many of the scribes and poets who helped shape the culture percolating in the Frisco Bay Mussel Group. Danny Rifkin, co-manager of the Grateful Dead, later founded Project Avary to provide support for children of incarcerated people. Jerry Yudelson went on to publish over a dozen books on green design and architecture, and even served as the first director of Jerry Brown’s SolarCal initiative in the late 1970s. Bonnie Sherk was a co-founder of The Farm, and continued her work to integrate art and nature in an urban environment in the years that followed with many projects, including her Living Library native plant corridors that connect Bernal Heights to Glen Canyon. Jack Wickert was another co-founder of The Farm who drove taxi and lived in a houseboat on Mission Creek all his life. He was in the middle of countless underground San Francisco projects. Vicky Pollack fell in with the Diggers when she arrived in San Francisco in the late 1960s and was a regular Frisco Bay Mussel Group attendee. She founded the Children’s Book Project which has given tens of thousands of free books to children over the years. Theo Ferguson participated in Bay Area Energy Action promoting solar and wind projects in southeast Asia, among many related projects over the years. And dozens of other people left unnamed took part as well.

At the second meeting in 1975, topics were identified for further research and ultimate action:

- • A county-by-county analysis of land available for gardens and farms.

- • a para- or meta-agency to monitor existent government agencies and industries for relevant information.

- • alteration of building codes to facilitate rooftop gardens, gray water reuse, solar generation and heating

- • land restoration projects

- • step-by-step transformation plan for San Francisco on 10, 20 and 50-year timelines.

- • identification of relic habitats, with public and protected access.

- • study of 85,000 acres of diked tidelands to plan removal of levees and restoration of wetlands; support aquaculture, mussels for food, cordgrass for fiber and grain

- • research tax resistance since local/federal taxes are used to destroy land.

- • design a food distribution system and organize people to do it.

- • garden corps—well-paid people to reclaim free, abandoned lands for urban gardens.

- • adding new sewage lines for gray water

- • block-by-block compost collection and trash sorting.

It’s remarkable to look at this list and recognize how many of these ideas have been implemented, integrated into local systems, or are being planned. Building codes have been altered in many parts of the Bay Area to accommodate rooftop solar, urban farming, etc. Graywater systems have been installed informally in dozens of locations, while the entirety of San Francisco’s Mission Bay neighborhood has had graywater built in, even if it’s not yet fully operational. Long-term plans to build a graywater recycling facility are on San Francisco’s municipal agenda. Curbside recycling, including compost, has been in place for most of the 21st century. Paid urban gardeners were eliminated by the Reagan Administration who ended the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA), but gardens have expanded well beyond 100 just in San Francisco thanks to the tireless efforts of volunteer labor across the city. Hundreds more urban gardens thrive in cities around the Bay Area on the same basis. Many of the formerly diked salt ponds have been opened to the Bay and are now part of the Don Edwards National Wildlife Refuge in the south Bay.

Salt evaporation ponds in distance, restored waterways in foreground, south of Dumbarton Bridge, 2014.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The Natural Areas Division of San Francisco’s Recreation & Parks Department has identified dozens of remnant habitats in San Francisco and is working diligently to preserve and protect them—a project that has been augmented and expanded by the successful restoration work carried out by the National Park Service in the Golden Gate National Recreation Area lands, especially in the Presidio. The People’s Food System that reached its zenith in 1978 disintegrated soon after that, but the principles of healthy, organic food were absorbed by new businesses that emerged in the capitalist marketplace, so that today a thriving organic food system exists, albeit one still dwarfed by the subsidies and market dominance of fossil-fueled agribusiness.

At the December 1975 meeting, the Frisco Bay Mussel Group turned their attention to the central concept of bioregionalism, the watershed. The Watershed Guide poster that accompanied the publication of “Living Here” in 1977 was the ultimate product of this line of inquiry, but in the notes it’s clear that many of the “Mussels” were interested in learning more about the vast interlocking waterways that make up the Bay and Delta. Detailed looks at the Napa River, Alameda Creek, the Russian River, the Coyote Creek system in Santa Clara county, groundwater basins and aquifers in each part of the bay, and the relationship of freshwater to salinity in the larger Sacramento River system all came under scrutiny in the meeting. This latter point highlighted the role of the Delta in the health of the Bay and already in December 1975, the group was turning its attention to Governor Jerry Brown’s plans for a Peripheral Canal.

With the successful printing of the map and booklet, the biweekly meetings in June 1977 focused on an inaugural event to be held in Sausalito (that never came off), as well as brainstorming how to distribute their new publications. But by early July, the Peripheral Canal began to dominate the meeting discussions. Realizing that the issue was a perfect fit for their burgeoning interest in the larger Northern California watershed (that could be destroyed by the Canal), different people tried to research the plan. They disclosed they had been unable to find any information about who beyond Governor Brown was pushing it, but it was clear that it was being done largely out of public view.

A late July meeting was held at the Ecology Center on Columbus Avenue where Jerry Meral of the California Department of Water Resources defended the plan as the best that could be hoped for, and that if Jerry Brown’s plan wasn’t followed, it could be much worse. Peter Berg and Rhodes Hileman rejected the necessity of shipping more water southward, and they learned that a following meeting with the Sierra Club a few hours later led to a similar reaction from at least one grizzled veteran there.

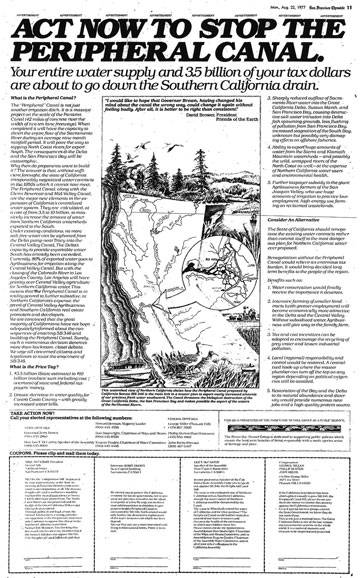

Encouraged by people near and far, the group delegated a committee to write a full-page advertisement to appear in the San Francisco Chronicle denouncing the Peripheral Canal. Following a well-established technique, coupons at the bottom of the ad gave readers the chance to quickly affirm their opposition to the Canal by clipping and sending them to local and state politicians (one coupon was to send in your resignation from the Sierra Club, due to their willingness to cave in to the Canal). The money was raised, the ad written and designed, and when published, set off a flurry of activism around Northern California. Even politicians whose politics were far removed from the folks of the Frisco Bay Mussel Group (e.g. the Contra Costa County Board of Supervisors) excitedly reprinted the ad and distributed thousands of copies to their constituents. The effort to rush through approval at the state legislature ground to a halt and ultimately was forced to go on a statewide ballot years later in 1982, where it was resoundingly defeated.

Full page ad in the San Francisco Chronicle in August 1977 to galvanize protest against the Peripheral Canal proposed for the Sacramento/San Joaquin River Delta.

When Jerry Brown was re-elected as Governor for the third time in 2010, he resurrected his old plan, now justified as a “solution” for the seismic vulnerability of California’s water supplies, rebranded as “delta tunnels” rather than a canal. Even this effort stalled, and when Gavin Newsom became Governor after two Brown terms, he downsized the plan to one tunnel from two, and that too has failed to pass the legislature. The first loud public opposition mounted by the tiny Frisco Bay Mussel Group has spared the citizens of California decades of disaster.

Right-wing agribusiness-financed hysteria dots the landscape throughout the Central Valley. But building any system to divert more fresh water from Northern California’s rivers to San Joaquin Valley agribusiness and Southern California cities will kill the Delta and ultimately the San Francisco Bay.

By January 12, 1978, the Mussel group (still 18 in attendance) was running out of steam. In Eric Noble’s minutes he writes, “Everybody’s busy, the group is tired, all of us discuss every detail for unimaginable lengths of time—until somebody volunteers to cover the responsibility out of impatience or disgust…” Linn House points out that after their successful publishing effort the “original concerns of the group were overshadowed by the pressing demands of issues like the peripheral canal and we began to resemble an issue-oriented conservation organization… There is still nobody to speak for other species.” A brainstorming session ensued, with proposals to open up (daylight) a city creek, help Kaliflower build a windmill to pump water from their new well (at 23rd and Shotwell), form an Oakland group to push Lake Merritt toward bioregional values, meet once a week on a hilltop to watch the sunset, take ‘exploring the city’ walks, breaking up into three study groups… John L. says “most of us are hardcore meeting haters.” Felicity “notices that ‘long silent pause’ when it comes time to volunteer.” Jane Q. notes that “energy commitments are limited—can’t get enough help with things so the limits of human energy cause us to filter out and do only the most pressing things…” And the final note from the final meeting ends with “Etc. Etc. Back & Forth. A dog fight. A busted glass. A cat played the piano with his feet… Somebody mumbled something about ‘die-hard anarchists’ as they went out the door.”

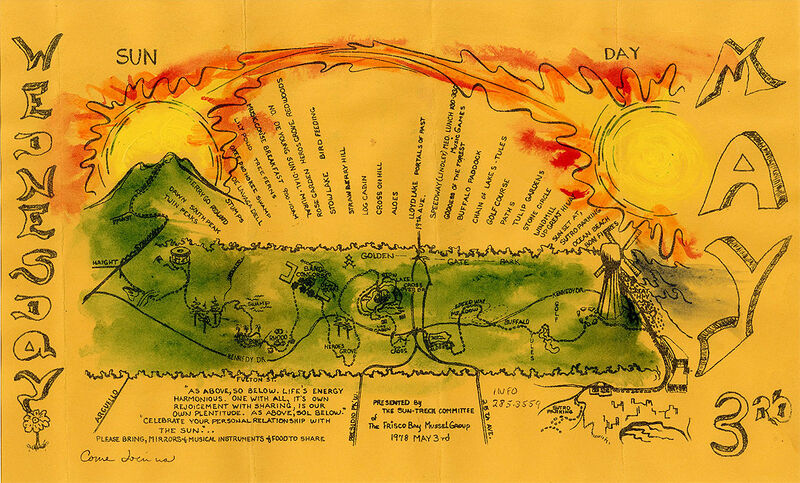

There was still a solar presentation scheduled for the meeting two weeks later, but no notes exist. A flyer does exist for an all-day “Dawn Perambulation” from Twin Peaks through Golden Gate Park to Ocean Beach on May 3 1978.

A May 3, 1978 dawn perambulation from Twin Peaks to the Beach, sponsored by the Frisco Bay Mussel Group.

Efforts folded back into Planet Drum after that time, with publishing and performing to promote bioregionalism and “Green City” organizing going on to the present.

A Black-necked Stilt thriving in the restored wetlands of the south bay, 2014.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Hundreds of Elegant Terns crowd a sandbar in the restored Crissy Field lagoon, 2022.

Photo: Chris Carlsson