Powell/Schuman Sedition Trial

Historical Essay

by Tom Powell

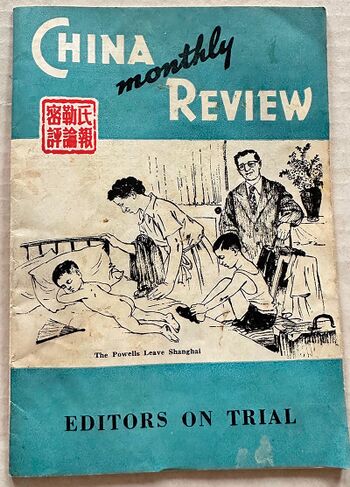

Powell family sails for the USA on aboard the S.S President Wilson in 1953.

Photo: Powell Family Archives

The most repressive courtroom action of the US government stemming from the events of the Korean War was the federal indictment and show trial of the Powells. Bill Powell was indicted on 12 criminal counts under US sedition statutes. Sylvia, who was the China Monthly Review’s managing editor, and Julian Schuman,(4) the Review’s associate editor were each indicted on one count of conspiracy to commit sedition.

People’s China, (PC1953-06); This supplement issue of People’s China contains the testimonies of Col. Roy M. Bley, supply chief for all bomb deliveries at K-3 Airbase, and the three testimonies of Col. Frank H. Schwable which laid out the entire US germ war operation including Japan, Korea and China, essentially, from the Pentagon to the battle field. This supplement issue of PC also contains several eulogies to Stalin who had just died.

Bill and Sylvia Powell returned to the US in 1953 after a decade of witnessing world history in China. The China Monthly Review had folded. The US Post Office had cut its subscription base in the US, and the advertisers had fled Shanghai, driven away by Bill’s political opinions and the rules of the new Chinese government. Bill wrote in July 1953, the last issue of The Review,

We are especially glad that we managed to stay around long enough to see the Chinese people put an end to the old state of disorder and start building a new life for themselves. It has been one of the great periods of history and we were particularly fortunate to have been able to witness it at such close range. . .We shall be returning to our own country, but we shall always remember these years in China, the long struggle of the Chinese people for a better life and their ultimate success.(5)

The announcement of the magazine's closure was met with a mixture of gloating and disdain from the American press. Bill Powell was denounced in Time magazine for turning his father’s magazine into a “mouthpiece for the Chinese Reds.” He was pilloried in Newsweek, US News and World Report, and the New York Mirror, and a hostile anti-communist political atmosphere fanned by the news media faced the Powells on their return to the US.(6)

Bill and Sylvia disembarked from the S.S. President Wilson at the port of San Francisco with John and me in tow. On board they had each been approached by CIA and FBI agents wanting to recruit them to become informants. They were reminded that they had few assets, few employment opportunities, and they faced possible legal problems which could be overlooked with their cooperation. On top of that arm twisting, the Review’s large and bulky library of 5000 volumes which JB had begun in 1917 was impounded by US Customs officials.

The first order of business was to visit family. As my parents had met and married in China and neither had returned stateside in the interim, there were a lot of new in-laws on both sides, new grandchildren, aunts, uncles and cousins to meet. Sylvia’s father, John Campbell, had died at the start of WWII and Bill’s father, JB Powell had died shortly after the war, so my brothers and I were raised without grandfathers. After traveling around the country visiting family, my folks returned to the West Coast and settled our family in San Francisco. Sylvia went to work for a child advocacy foundation. Bill lectured on China politics and taught himself carpentry and plumbing from manuals and began a fixer-upper-house-flipping business.(7) Later, my brother Campbell was born, and all three of us boys grew up learning carpentry and plumbing skills.

When the sedition indictment was handed down in 1955, Bill and Sylvia had little choice but to vigorously fight the charges. Any plea bargain deal would have sent Bill to prison for many years and torn our family apart. Fortunately for us, there were many good people, including many who had already been harmed by McCarthy witch-hunts who rose to support this new attack on civil liberties, on freedom of the press, and on them personally. With excellent attorneys and an energized support base from the political left throughout the Bay Area, the Powells opted as their legal strategy to vigorously fight the government’s charges. Their task would be to convince a jury of the truth of their Review articles. During the Korean War, the US had, in fact, stalled the peace talks for over a year, and the US had, in fact, engaged in an aerial campaign to spread disease contagion all over North Korea and Northeast China in 1952.

This tactic of unflinching defense was popular and energized the Powells’ supporters who were thoroughly disgusted by now with Congressional red-baiting. But it was also exceedingly risky if it failed as each count of the indictment carried a maximum penalty of 20 years and $10,000 fine.

US District Court Judge Lewis E. Goodman was put in a difficult situation where he had to weigh the defendant’s right to a free and fair trial against the government’s claims for secrecy and protecting national security. Goodman kicked the ball back to the government’s court. If State didn’t validate [defense attorney A.L.] Wirin’s passport, he would have no choice but to dismiss all charges. There followed an intense debate between Justice, State, and Defense. The Joint Chiefs of Staff could see how this trial might go very badly for the military if the truth about the Biological Warfare (BW) campaign came out.(8) It could unravel all the way back to [Imperial Japanese biowarfare scientist] Ishii Shiro. They argued to drop the charges and bury the case in slander.

On the other side, the State Dept. was eager to prosecute; it intended to make an example out of Bill Powell and the Review. Both State and Justice had embraced the policy of rolling back communism, foreign or domestic, as announced in NSC68; both executive departments had shifted sharply to the right under President Eisenhower, and both were politically invested in the prosecution. And so the trial proceeded. The case was prosecuted by Assistant US Attorney Robert Schnacke.

Wirin left China with reams of testimony. The Powell/Shuman case would be the crowning civil liberties achievement of Wirin’s long and distinguished legal career. A month before the trial was to start in Dec. 1958, Wirin suffered a debilitating heart attack.

Judge Goodman refused to delay again the long-delayed trial to await Wirin’s recovery. With Wirin sidelined to an observer role by his doctors, the Defense brought in Charles Garry to handle courtroom examinations. Wirin later recovered, but considering all his legwork and his expectations for the case including his extended trip to China, and then, to be sidelined for the main event, which in turn sputtered—it must have been a big letdown.(10)

The Powells’ second attorney, who became lead attorney following A.L. Wirin’s heart attack, was Doris Brin Walker. Walker grew up poor in Texas, put herself through school at UCLA, then law school at UC Boalt Hall where she was the only woman in her class. Doris Walker had joined the American Communist Party while in her early 20’s and remained a member all her life. In the 1970’s, Walker successfully defended Angela Davis on the charge of murder in the George Jackson escape attempt. Walker was small in size but a formidable intellect.

The trial began in January 1959 but ended three days later with a mistrial being called by the outraged Judge Goodman. The Oakland Tribune had run a banner headline declaring “POWELLS FLAYED BY TRIAL JUDGE.”(9)

What brought this about was another Schnacke misstep. During the Senate Internal Affairs subcommittee hearings, Alva Carpenter had produced US POWs to relate how they had been severely punished for refusing to read the Review as part of their “re-education” classes in the Yalu River POW camps. Schnacke intended to follow the same path to emotionally soften up the jury with POW horror stories. However, Doris Walker objected. According to statute, the crime of sedition can only occur within the territorial boundaries of the United States and its maritime possessions. What happened in POW camps in North Korea was out of the statutory jurisdiction of the charges and not admissible evidence in this trial. Judge Goodman had to sustain the defense objection. As a result, half of the government’s witnesses would have to be dismissed.

With the jury sent out of the courtroom, Goodman explained to Schnacke the limitations of the sedition statutes. Why Schnacke was unaware of this critical fact is anybody’s guess, but clearly it was a tactical error. Why Judge Goodman hadn’t raised this issue before the trial began is also bewildering. Goodman then told Schnacke in open court with the press still in attendance, that the prosecution had a prima facie case which could sustain a conviction for treason, and that he had charged the Powells under the wrong criminal statutes. This took place in the morning court session. The Oakland Tribune was an afternoon paper. Its reporter dashed out of the courtroom to the lobby phone booth to call in this scoop to his editor. The banner headline appeared on street newsstands across the Bay Area within two hours.

The potential of the Powell/Shuman sedition trial to blow wide open the whole scandalous US biological warfare story in 1959 was quashed with the shutdown of the trial. The public would not be privy to the truth of BW in Korea, and the story quickly fell out of the news. The government got what it wanted without a conviction; it avoided an outright acquittal, it silenced critics, and it thwarted any possibility of a Congressional committee investigation into the conduct of the Korean War. It made an example out of Bill Powell, and it made the sordid topic of US BW in Korea disappear. It made the topic disappear for twenty-one years, until 1980 when Bill Powell dragged the whole stinking BW carcass under the public nose again with his revelations of the Ishii Shiro deal.

The Powell/Schuman case hung in limbo until 1961 when new Attorney General Robert Kennedy, reviewing the Justice Dept caseload, recognized that the government would not be able to produce the two corroborating witnesses needed for a treason conviction. The opportunity for the truth of BW in Korea to come out was missed. History had moved on, and Kennedy quietly dropped the charges. The Powell/Schuman Trial showed how easily in our American democracy the truth can be legally censored by the government.

Notes

4. Julian Schuman later returned to China where he spent the rest of his life as a journalist, and sports editor, and published several books including his memoir. Julian Schuman, Assignment China, Foreign Language Press, Beijing, 2004.

5. John W. Powell, China Monthly Review, July 1953, p,132.

6. O’Brien gives a good discussion of this topic. See: Neil L. O’Brien, An American Editor in Early Revolutionary China: John W. Powell and the China Weekly/Monthly Review, Routledge, New York and London, 2003, pp. 250-252.

7. See: John W. Power, “My Father’s Library”, Chico News and Review, 07/26/06, and Robert Speer, “Dirty Secrets”, Chico News and Review, 07/26/06.

8. O’Brien’s explanation of the legal maneuverings and strategy leading up to the trial is highly informative. Neil L. O’Brien, op. cit. pp. 269-280.

9. Bill Bancroft, “Defendants Case Hit by U.S. Jurist”, Oakland Tribune, January 29,1959, p. 1.

10. I’ve heard two versions of this story. Charles Mattox, treasurer of the Powell defense committee told me one version when I interviewed him for his oral history in 1993. After my father died in 2008, I interview Doris Brin Walker and got her explanation of events. Unlike Doris who also loved camping and became a regular presence and close family friend, A.L. Wirin never responded to Sylvia’s cards and invitations and dropped contact with my parents once the trial was over.

This account is excerpted from The Secret Ugly: The Hidden History of US Germ War in Korea by Thomas Powell, Edgewater Editions: 2023.