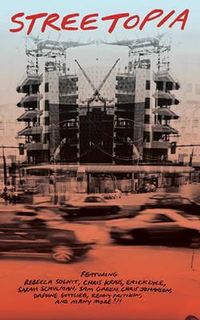

Redevelopment vs. Ecotopia

Historical Essay

by Erica Dawn Lyle

The view down Beale Street towards 101 California, 2017.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The battle of competing realities in San Francisco is often characterized as a battle between “downtown”—coalitions of corporate business leaders, often literally represented in the past by the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency (SFRA)—and “the neighborhoods,” often shorthand for the city’s activist progressive Left. The ideology of the downtown interests can at times seem as outwardly authoritarian as that of a sci-fi villain. Indeed, the racial and economic cleansing matter-of-factly envisioned in this excerpt from a master plan on redevelopment could have easily come from [Philip K. Dick's] The Man in the High Castle:

If San Francisco decides to compete effectively with other cities for new “clean” industries and new corporate power, its population will move closer to “standard White Anglo-Saxon Protestant” characteristics. As automation increases, the need for unskilled labor will decrease…The population will tend to range from lower middle-class through upper-class…Selection of a population’s composition might be undemocratic. Influence on it, however, is legal and desirable.

The above comes from Prologue For Action, a report commissioned in 1966 by a lobby of downtown corporate executives from San Francisco Planning and Urban Renewal (SPUR). With their dreams of “urban renewal,” these heads of San Francisco-based corporate giants such as Standard Oil, Bechtel, Del Monte, Southern Pacific, Wells Fargo, and Bank of America imagined remaking the heavily unionized and industrialized “Frisco” of the 1950s as a future utopia for unregulated white-collar business.

While Dick imagined future versions of San Francisco, he never set his novels in a devastated, post-apocalyptic San Francisco. Instead, it was the city’s own business leaders that boldly imagined—and carried out in real life—the destruction of much of the existing city.

In 1956, SFRA began the first of two projects in San Francisco’s Fillmore District, slashing the neighborhood in two with a widened Geary Boulevard—a move Burnham would have been behind—while demolishing over sixty square blocks of housing. Some 17,500 African-American and Japanese residents saw their homes bulldozed. The Port of San Francisco—the home of the unionized dockworkers who had organized the 1934 General Strike—was moved across the bay to Oakland. The colorful produce district along the waterfront was removed in 1959, its warmth and human buzz replaced by the four identical modern hulks of the Embarcadero Center.

Sterile apartments rise along Fillmore Street where once a thriving African American neighborhood prospered.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

After basically bulldozing the African-American Fillmore and Japantown out of existence, business leaders sought to expand the downtown south across the historic border of Market Street. SFRA director Justin Herman said of the South of Market area, “This land is too valuable for poor people to park on it.” Beginning in 1966, some eighty-seven acres of land South of Market—including about four thousand housing units ringing what was then the city’s “skid row” at Third and Mission—were bulldozed to make way for office blocks, hotels, and the Moscone Center.

The battle between the forces of redevelopment and the city’s Left has profoundly shaped the city over the past forty years. As SFRA bulldozers remapped the city, the neighborhoods struck back with considerable resistance—including the surprising victory of the so-called Freeway Revolt, a grassroots effort in the 1960s to stop proposed freeways across Golden Gate Park and through the middle of historic neighborhoods. The neighborhoods have won other important victories over the years, including the passage of ballot measures limiting downtown growth, the return of district elections for the Board of Supervisors, and the important decision not to rebuild the Embarcadero Freeway after it was heavily damaged in the 1989 earthquake. While the SFRA’s legacy is writ large across the city in the form of sterile 60s era shopping plazas, apartments, and government buildings, the neighborhood forces have inscribed a popular network of bike lanes atop the city’s streets.

Future site of Warriors Arena in Mission Bay, in this 2016 photo it has been striving to return to wetlands at its location at the mouth of Mission Bay.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

For inspiration, the city’s Left has also looked to science fiction. Ecotopia, a 1975 work of speculative fiction by Ernest Callenbach, is set in a near-future San Francisco reimagined as ecologically sustainable utopia. Man lives in harmony with nature in a rewilded—yet still decidedly urban—socialist paradise. Optimistically set in 1999—just twenty years after Northern California, Oregon, and Washington have seceded from the United States in a peaceful revolution to form the titular nation—Ecotopia outlines a compelling vision of a tantalizingly possible autonomous San Francisco. With its worker-owned collectives, municipally-owned utilities, locally grown food, and free bikes, Ecotopia would inspire much of the entire Progressive Left’s political agenda in the city for generations.

Written when much of the city was still literally in ruins from redevelopment, Ecotopia was a deliberate rejoinder to the SFRA claims that this blitzkrieg approach to city planning actually “improved” or “cleaned up” so-called blighted neighborhoods. But a tour of Ecotopia is to look at forty years of a different set of not-quite-realized dreams for San Francisco. On Ecotopian the paths of Market Street ancient creeks once filled in have now been uncovered and restored, creating a “charming series of little falls, with water gurgling and splashing, and channels lined with rocks, trees, bamboos, and ferns.” A surplus of organic food is produced close to home. The Sunset District and Golden Gate Park have been allowed to revert back to native grasses and trees, to which local hunters can travel to on the city’s free bikes or electric buses to hunt the resurgent deer population. Everything is recycled—in fact, materials that do not decompose are no longer used. Callenbach’s vision is carefully argued, rational, calm, yet in one regard, wildly optimistic: this Utopian city has come about not from the blank slate caused by war or plague or apocalypse, but from a peaceful grassroots secession campaign. The results are not an Edenic return to wilderness but a functioning socialist city in which man lives more sustainably amidst nature.

The Potrero Hill Community Garden at 20th and Vermont overlooking one of the world's best views, a decades-old project in urban reinhabitation inspired by Ecotopian thinking.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Ecotopia had a redevelopment agenda of its own—the economy of the fictional republic was driven in part by the many new jobs to be found dismantling gas stations, highways, and other ecologically unsustainable relics of the old way of life. Yet, in contrast to SFRA, Ecotopia proposed a creative destruction of certain aspects of the present day city in order to make space where a new set of social relations and material improvements might flourish. Instead of a future in which an area was “improved” for the enrichment of a few at the expense of many, Ecotopia offered a powerful and realizable dream of the many working together for the benefit of all.

Excerpted from Streetopia, in the essay "The Uses of Market Street"

See other parts of this essay: