San Francisco Housing Authority 1937-1965: The Early Decades

Historical Essay

by Dr. Amy L. Howard

This excerpt originally appeared as Creating “A Way of Life”: the SFHA’s Early Decades, 1937-1965 in Chapter one of More Than Shelter (see below for copyright and book information)

Holly Courts, the first public housing completed in San Francisco, under construction here on March 4, 1940, next to a soon-to-be-demolished firehouse.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

During its first three decades, the San Francisco Housing Authority (SFHA) set out to plan, promote, and build public housing projects that would improve the neighborhood and lives of the tenants living there while replacing substandard buildings across the city. At the same time, the combination of policy choices, leadership decisions, and the organizational structure of the Housing Commission created a shaky foundation for sustainable, decent, inclusive public housing communities. Like many other housing authorities across the country, and in line with federal guidelines, the agency enacted strict requirements and screening processes for tenants to reside in the new public housing projects.(15) The agency also adopted and upheld race-based policies that would impact the public housing program for decades. Granted control over tenant selection by the federal government, the SFHA staff, like other agencies across the nation, preferred “complete,” “stable” families—two parents with children and an employed father—holding fast to the belief that “the experience of living in public housing would make their children better future citizens.”(16) Applicants had interviews with social workers, employment verifications, credit checks, police record checks, and home visits to inspect the “inadequacy” of their living conditions and to assess the family’s ability to adapt to a new environment.(17) The SFHA also required that one member of the family, “preferably the head,” be a US citizen.(18) Once admitted, public housing residents had to follow strict regulations dictating paint color, laundry schedules, visitor policies, yard maintenance, and income levels.(19) In 1942, the SFHA adopted a “neighborhood pattern policy” based off of federal guidelines that effectively segregated future public housing projects by race and ethnicity. Taken together, the application process and resident restrictions, along with the SFHA’s management practices and policies, created restricted and exclusionary public housing in San Francisco.

Arnold Taube unpacking his belongings with the help of his daughter Rosanne, at Sunnydale housing project, March 3, 1941.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

George Fern also moving in on March 3, 1941 to Sunnydale.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

The SFHA’s aims of molding citizens in public housing and contributing to the wider community through subsidized housing were evident in the agency’s first public housing project, Holly Courts, located in the Bernal Heights neighborhood. Widely hailed in the architectural press as the first public housing project “West of the Rockies” and praised for its “refreshing Modern design,” Holly Courts opened in June 1940.(20)

Notable architect Arthur Brown, Jr., whose designs for the Golden Gate International Exposition and Coit Tower in San Francisco, and federal offices in Washington, DC, were widely known, designed the SFHA’s first public housing units.(21) The modern project consists of ten two-story blocks with separate entrances, flat roofs, and small garden plots behind or in front of each two-story row house dwelling.(22) Interior courtyards, gardens, and playgrounds provided communal outdoor space for residents. The new project replaced “118 insanitary dwellings units.”(23)

The design and amenities, as well as the new residents themselves, were hailed by the SFHA as valuable assets to the surrounding neighborhood. Housing Commissioner Marshall Dill described Holly Courts as “integrated into the neighborhood” with residents who “will trade in local stores, attend local churches, [and] send children to local schools.”(24) Holly Courts, he claimed, would seamlessly fit into the neighborhood with a social hall “for the use of the community” and “sand boxes, slides, swings [and] play spaces” for “all the children in the neighborhood to use.” The new families moving in, Dill assured neighboring property owners, had been carefully selected by the SFHA to ensure “they believed in the wholesome values of family life” and would make “a contribution to the community.”(25) Endorsing public housing as a transitional space for morally upright, industrious families en route to the middle class, the SFHA set out to create a community based on white, middle-class, culturally constructed norms of family life and behaviors.

The Housing Authority demonstrated its commitment to this specific notion of community by aiding tenants in their transition to living in federally subsidized housing. Drawing on European public housing strategies, the Housing Authority hired a “Consultant for Homemaking.” In this role, Else Reisner had intimate knowledge of the new residents, having previously worked with the Tenant Selection Division researching the applicants’ backgrounds to determine their eligibility. As a consultant, Reisner was charged with creating a “way of life” for residents to emulate.(26) From furnishings to childcare, Reisner instructed tenants on the “best” way to live. Using a budget based on tenants’ average income, Reisner furnished a model apartment for incoming tenants to tour. She also provided guidance and answered questions about furnishings and organizing apartment space. After tenants moved in, she aided them in arranging their apartments and establishing a wash schedule for shared clotheslines, and she attended to requests for towel bars, hooks, and other items. Reisner also provided training on how to use the gas stove, heater, and electric washing machines. Caring about tenants’ domestic concerns and working to eliminate resident dissatisfaction, Reisner reasoned, facilitated cooperation and created a strong public housing community made up of selected tenants living according to SFHA standards.(27)

Further, acknowledging the continual struggle to overcome opposition to the new public housing program, Reisner claimed, “Happy, satisfied tenants constitute the most important factor in a sound and effective public relations program.”(28) As the nascent public housing program tried to grow, publicity and promotion seemed as important as building design and construction in ensuring the SFHA’s future success.

The SFHA’s focus on these “deserving” tenants and the importance of public housing in strengthening communities, the city, and democracy in the nation permeated the agency’s publicity campaign during its first decade. Through a multimedia marketing campaign, the SFHA promoted its agenda to “provide the framework for a way of life for its tenants . . . set within the greater framework of the community and the city.”(29) The elaborate display at the Golden Gate International Exhibition in 1939-1940 was just the beginning of the SFHA’s publicity efforts. The model apartment at Holly Courts was open to the public for tours that included high school and college classes in the Bay Area.(30) These early marketing efforts promoted public housing for its potential to mold deserving citizens—as defined by the SFHA—in support of a healthy democracy.

Donald Sanchez, Frances Bonnici, and Mrs. Alice Stinchcomb in a Sunnydale apartment in 1941.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

San Franciscans had a variety of other ways to learn about the new housing program as well: radio spots, newspapers articles, film screenings of “Housing in Our Time” and “Our City,” and public talks by the Housing Commissioners all promoted the public housing program amid increased skepticism.(31) Using donated radio time, the Authority presented “The Housing Reporter,” a weekly dramatization about San Francisco’s public housing program.(32) Along with these radio spots, the SFHA commissioned its own film to depict “in dramatic style” the agency’s methods for “solving the age-old problem of providing more than four walls and roof as a center of family life.” Directed by WPA photographer William Abbenseth, “More than Shelter” was screened at the SFHA office, in churches, unions, and other organizations across the city. The film became a popular tool for educating citizens on “the ‘whys’ and ‘hows’ of the low-rent housing program.”(33)

Garnering support for the nascent public housing program meant quelling citizens’ concerns about two different kinds of values: the values and morals of public housing tenants and property values. The SFHA had to contend with San Franciscans “who held fantastical ideas concerning the type of persons to be housed and the effect on private property.”(34) The SFHA, like other housing authorities across the country, stressed the “morality” of public housing and through the 1950s turned away applicants who might present a moral or financial risk.(35) The marketing campaign also championed the new public housing projects for replacing blighted buildings and improving safety and sanitation in neighborhoods. These efforts, the agency argued, would lead to increased property values for neighboring landowners.

As the SFHA began completing public housing projects across the city, the agency branded itself as an integral player in building the health of the city and the nation. For its seal, the authority emphasized its commitment to both the city’s past and future by selecting the “legendary Phoenix, fabulous eagle of antiquity and patron bird of San Francisco” (the bird also adorned the city’s seal). The 1946 minutes of the Housing Authority Commission explained the meaning of the oft-displayed SFHA emblem:

Arising from the flames it commemorated the indomitable and virile city that arose again time after time from the ashes of disastrous early fires with new strength and spirit. In this seal the Phoenix symbolizes as well the building of good homes and a better city from the ashes of destroyed slums. The five stars represent the five low-rent developments constructed during the Authority’s first decade after its founding in 1938. The scroll beneath carries the moving message “In love of home the love of country has its rise,” by Charles Dickens, the motto of the SFHA.(36)

Through its seal and motto, the Housing Authority aligned itself with San Francisco’s history of renewal after the fire and earthquake of 1906 while advocating a particular view of community and citizenship. By creating modern projects housing selected tenants subject to numerous regulations, the SFHA pledged to improve tenants and neighborhoods. In selecting Dickens’ phrase for the SFHA motto, the Housing Commissioners also demonstrated their belief in environmental determinism’s premise that good homes produce good citizens. Public housing, seen by the SFHA as the training ground for middle-class living, would, in officials’ eyes, inculcate tenants on how to behave as they worked and waited to move up and out of federally subsidized housing.

The SFHA promoted itself, in part, to secure buy-in from city residents to build more public housing in neighborhoods across the city. The agency opened Holly Courts (118 units) in 1940, Potrero Terrace (469 units) and Sunnydale (767 units) in 1941, Valencia Gardens (246 units) and Westside Courts (136 units) in 1943. Located in the Western Addition, Westside Courts housed African Americans and “a few white families”; the other 1600 new housing units had no black tenants.(37) Plans to build six other projects were delayed by World War II, as the country shifted its resources to the war effort.

Sunnydale construction, November 20, 1940.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

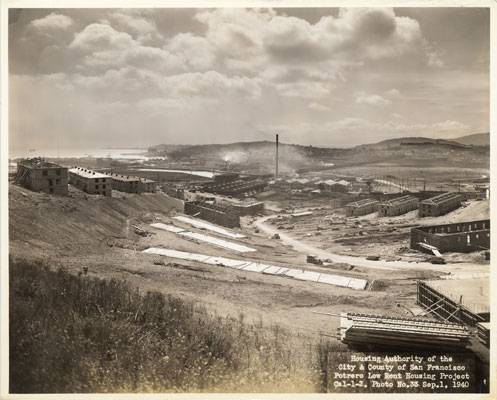

Construction of Potrero Terraces, 1940.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

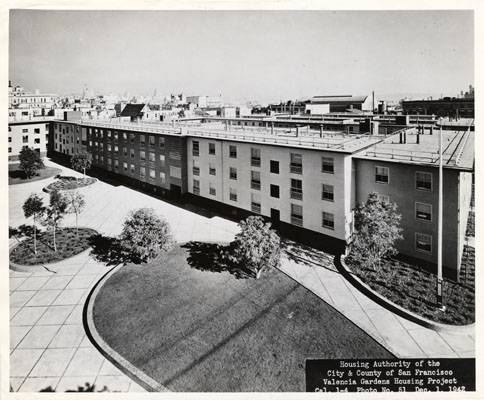

Valencia Gardens courtyard, 1942.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

The onslaught of military, government, and civilian workers arriving in the Bay Area exacerbated the pre-war housing shortage and created a housing crisis as the population of San Francisco increased by 90,000 between 1940 and 1942. With war workers in the region reportedly living in converted sheds and chicken shacks, and thousands of new arrivals flooding the area each month, the SFHA responded to the federal Lanham Act and local conditions by prioritizing the housing needs of military families and building temporary war housing under federal ownership.(38)

The wartime shift to temporary housing demonstrated the SFHA’s emerging administrative acumen and the positive potential of collaboration across city departments and with unions and the business sector. SFHA wartime construction included 5500 units of temporary housing for naval dockworkers and their families in southeast San Francisco. Together the SFHA and federal government leased 500 acres of land to construct Hunters Point. The SFHA successfully led infrastructure planning on the temporary units, working with city departments and trade unions to bring roads, sewers, schools, police, and fire to Hunters Point.(39) Along with these necessities, the SFHA also provided a library, social hall, a gymnasium that held a variety of activities including dances, volleyball, and boxing, and a government-funded daycare center. In collaboration with the city’s public health department and the US Public Health Service, the SFHA also opened a health center, well baby clinic, and infirmary for war workers. Transportation to the Naval Yards was provided as were a range of other services from barbershops to a movie theater. This “city within a city” eventually housed a population of 35,000.(40) The extent of interagency cooperation in constructing wrap-around resources for tenants waned in the post-war period when the SFHA returned to its original mandate to house low-income families. Likewise, the level and amount of services provided to Hunters Point residents proved more robust than the meager amenities eked out of tight federal funding allocations for permanent public housing projects.

The most significant difference, however, between the SFHA’s oversight of temporary war housing and the permanent public housing program was arguably not tied to resources or inter-agency and cross-sector cooperation. Rather, Hunters Point was racially integrated. Perhaps because it was temporary housing or because of the dire housing shortage, the SFHA went against its own stated policy and practice, and opened Hunters Point to all civilian workers regardless of race. By 1945, Hunters Point had grown to 20,000 residents, one-third of them black. As historian Albert Broussard has described, Hunters Point emerged as “one of the most thoroughly integrated communities in San Francisco.”(41)

Despite maintaining the color line in its five permanent public housing projects, the SFHA documented and seemingly celebrated racial integration at Hunters Point. In 1944, the Beacon, the SFHA’s newspaper for Hunters Point area residents, hosted a photo contest. The winning photo was taken at the Navy Point Infirmary. In the photograph, Quentin Anderson, a smiling white little boy and a patient at the infirmary, sits on a bed feeding a black baby girl, Joy Knightson, with a bottle. The San Francisco Housing News reported that the five-month old baby had refused to eat until Quentin fed her.(42) The image—reproduced in other SFHA publications and, according to the SFHA, in over 30 publications nationwide—captured an image of racial accord that, ironically, the SFHA was simultaneously stymieing through its policies, Commission appointees, and politicized leadership within the permanent public housing program.

The democratic ideal of public housing promoted through the SFHA’s publicity campaign, including the widespread image of racial integration at Hunters Point, began to weaken under the agency’s race-based policies and political gamesmanship. Even as the SFHA emphasized its aim of strengthening individuals and communities, Commissioners wrestled with the explosive issue of integration in the permanent public housing program. What would it mean to integrate public housing? How much more resistance would neighbors bring to bear on site selection and land purchases if public housing “in their backyard” was integrated? Following what became a well-established pattern in housing authorities across the nation, the SFHA commissioners pledged to uphold the federal “neighborhood pattern policy” guidelines. The Housing Commission passed Resolution 287 in 1942.(43) The neighborhood pattern policy stated that “in the selection of tenants for projects of this Authority, this Authority shall act with reference to established usages, customs, and traditions of the community with a view of the preservation of public space and good order and shall insofar as possible maintain and preserve the same racial composition.”(44) Put into place as San Francisco’s African-American population began to increase dramatically due to wartime in-migration, the policy served as a conservative response to the city’s shifting demographics. Racial integration at Hunters Point was a wartime anomaly. The impact of the neighborhood pattern policy—which allowed Housing Authority staff to select and place public housing residents based on the existing racial and ethnic composition in a neighborhood—reverberated for decades in San Francisco.

The strain of the city’s shifting demographics, the housing shortage during the war, and the philosophical differences among the appointed housing commissioners led to a politically motivated shake-up in the SFHA Commission a mere five years after the organizational structure was established. In September 1938, after Wilder’s short time as Executive Director of the SFHA, the commissioners unanimously appointed to that position local architect and urban planner Albert Evers, who had experience surveying slum areas and designing low-rent housing.(45) Evers shepherded the agency through receiving federal approval for several public housing projects and worked to develop processes and systems for the growing organization. Evers’s skills, however, were overshadowed by the increasingly polarized views of Housing Commission members. Veteran commissioners Marshall Dill and Alice Griffith regarded public housing as a critical vehicle for social reform; in contrast, newer mayoral appointees E. N. Ayer, William Cordes, and Timothy Reardon were, as historian John Baranski put it, “determined to limit the authority in the areas of civil rights.”(46) These tensions finally erupted in a showdown. On August 17, 1943, a special emergency meeting of the Housing Commissioners was called to hear the grievances of Management Division head John Beard and a few other employees who resigned in protest over Evers’s creation of a new Maintenance Department. During the meeting Commissioner Ayer limited the testimonies to two employees who spoke against Evers. After the employees spoke, he quickly proposed a motion calling for Evers’s resignation. Cordes and Reardon seconded the motion, and their majority vote forced Evers out without cause. The three commissioners then appointed John Beard as Acting Executive Director of the SFHA. Beard had started at the SFHA in the Tenant Selection division, was then promoted to the Management Division, and had become the chief of that department. He had no training or experience in planning or architecture. He did, however, have ample experience in “filtering out nonwhite applicants from white-only projects” from his work in the Tenant Selection division.(47) Appalled by the “unfair practices” of their fellow commissioners, Griffith and Dill resigned in protest the day after the meeting. Despite an outpouring of support for Evers from local, state, and national organizations, his dismissal and Beard’s appointment stood. Mayor Angelo Rossi filled the two vacated Commission seats with a social worker, Katherine Gray, and a labor leader, John Spalding. Both of these mayoral appointees, Baranski writes, “ensured that the SFHA leadership would not attack the city’s color line.”(48) The loss of the institutional knowledge shared by Dill, Griffith, and Evers, as well as their collective expertise in urban planning, housing, and architecture, left a void in SFHA leadership: the political jockeying within the organizational structure laid bare the inherent vulnerability in a system so easily shaped by patronage and politics.

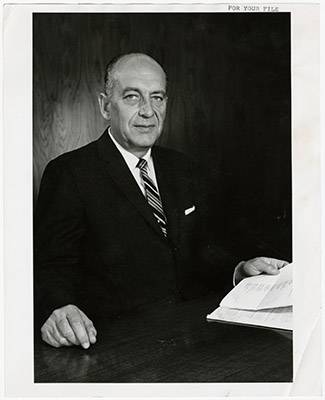

John Beard, segregationist head of the San Francisco Housing Authority for 22 years.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Under Beard’s leadership, the SFHA held fast to its segregationist policy and continued to shape and enforce the role of public housing as a place to mold compliant citizens. As newcomers continued to crowd into the city, the SFHA was only one of many players enforcing housing segregation. White private property owners, like their counterparts in the Northeast and Midwest, used restrictive covenants to confine African Americans to the Western Addition/Fillmore district and Chinese Americans to Chinatown. As the city’s population continued to swell and the housing crisis deepened, the fear of racial tensions resulting in violence intensified in the wake of the deadly 1943 Detroit race riot. In response to rumors of an impending race riot at Hunters Point in November 1944, Mayor Roger Lapham created the Committee on Civic Unity (CCU), a group of civil rights and housing activists charged with improving race relations with a particular focus on public housing.(49) While the CCU’s investigation showed that the alleged race riot was but “idle gossip,” the committee found discontent among white residents at Hunters Point and began focusing on improving inter-group race relations.(50) The CCU’s ultimate recommendation was for the SFHA to desegregate public housing and to support the creation of tenants’ associations, a position they would continue to advocate after the war.

Through its choice of architectural designs for public housing and its practice of prohibiting meetings of “a political nature” in its buildings, the SFHA under John Beard successfully curtailed tenant organizing during the first decade and a half of operation.(51) As the new head of the SFHA, John Beard had no intention of changing course or sharing power with tenants in any way. In his view, tenants’ organizations were “unnecessary and undesirable.”(52) With an eye towards other California locales, historian John Baranski argues, Beard may have feared the conflation of racial foment and tenant organizing. He had only to look at nearby Marin City and Richmond, California to see that tenants’ organizations could mobilize for change. In Marin City, tenants’ organizations had provided a platform for cross-racial dialogues and community-building among residents. African-American tenants in Richmond, California leveraged their tenants’ organization, as Baranski notes, “to demand better and more public housing, end discriminatory policies, and stop evictions.”(53) When their needs were not met, the tenants launched a rent strike, joining other public housing tenants nationwide who directly challenged housing authorities in the late 1940s. Despite continued pressure from the CCU and some PHA officials to support the creation of tenants’ organizations, the SFHA consistently refused to support tenant organizing. Instead, Beard opted to handle tenants’ problems individually, stating that the SFHA would “look with disfavor on any effort to organize the tenants for political reasons.”(54)

Wielding sole power over tenant selection, race-based placement, and management, with no input from the tenants themselves, the SFHA reinforced housing segregation patterns in the city and quashed criticism from public housing tenants. The agency’s actions increasingly came under fire. In November 1945, representatives from the NAACP, Communist Party, CCU, and CIO urged the SFHA to repeal the neighborhood pattern policy.(55) The SFHA refused. Commissioner Ayer used democratic principles to justify the Housing Authority’s position: As a “public body this Authority must follow the will of all the people. This has been the policy in the past and must necessarily be the policy in the future.”(56) Local activists continued to push for change, viewing public housing as a viable way to challenge the color line in the city’s neighborhoods. In 1946, the San Francisco Urban League, the CCU, the American Veterans League, and the San Francisco Council of Churches pressured the mayor and Board of Supervisors to replace the neighborhood pattern policy with “a non-color policy of first come, first serve.”(57) A citizen’s survey covering the five permanent public housing projects published the same year called on the SFHA “to revise its racial policy to permit minority groups in all public housing.”(58) The mayor responded to this growing public pressure by appointing Dr. William McKinley Thomas, the first African American to serve on the Housing Commission, when a vacancy opened up in 1946.(59)

The Board of Supervisors took a bolder step: in July 1946 they voted 9-to-1 for a resolution calling for the end of segregation in San Francisco public housing. The SFHA ignored the resolution as the Housing Commissioners demonstrated their autonomy from local governance. While some other housing authorities made strides in integrating public housing and supporting tenants’ organizations, the SFHA held fast to its policies under Beard’s leadership.(60)

When tens of thousands of families who had migrated to the city for war work decided to stay, San Francisco became “one of the Nation’s most critical cities in the lack of housing.”(61) In the immediate postwar period, the Housing Authority responded by focusing attention on constructing public housing projects delayed by the war. Rising land and building costs and the exhaustion of federal funds for public housing, however, stalled construction. It was only after Congress passed the Housing Act of 1949 that the SFHA finally had the funds to move ahead with its building program.(62)

The Taft-Ellender-Wagner bill that became the Housing Act of 1949 called for 810,000 units of public housing. However, by dividing power between local housing authorities and redevelopment agencies, the legislation in many ways bowed to private developers and real estate pressures. In anticipation of the federal legislation, the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency (SFRA) was established in 1948. Governed by mayoral appointees, the semiautonomous agency with “vast independent legal, financial, and technical powers and resources” grew into a pro-business urban renewal juggernaut. The vagueness of the Housing Act language and the focus on “urban redevelopment” opened the door for the construction of high-end apartments, parking lots, and other developments that were more lucrative and accepted than low-rent housing. In San Francisco, the SFRA used millions in federal funds over several decades to construct the controversial Yerba Buena Center and the Embarcadero Center, supporting a pro-business, pro-growth agenda that displaced thousands of low-income residents in a city where public housing demand outpaced supply.(63)

In California and San Francisco, state and local governments responded to the public housing provision of the new federal legislation in markedly different ways. The California state legislature aimed to curtail public housing construction, passing Article XXXIV in 1949 that required voters to approve any construction of new public housing projects. Locally, the CCU seized on the federal act and allocation of 3000 units of public housing in San Francisco to continue to push for desegregation. Each SFHA application for federal funds had to be approved by the Board of Supervisors. Under the leadership of Director Edward Howden, the CCU convinced Board Supervisor and future mayor George Christopher to add a clause forbidding segregation in public housing to the SFHA’s application. The Board of Supervisors approved the application with the nondiscrimination clause.(64) Beard and the Housing Commission balked, postponing the submission of the application to the federal government. With the city’s critical housing need and millions of dollars in construction, administrative, and maintenance jobs hanging in the balance, the Board of Supervisors, activists, and eventually the local press blasted the SFHA for refusing to desegregate public housing and potentially foregoing federal funding due to delays. Supervisor George decried the neighborhood pattern policy as “a policy of discrimination.” The San Francisco News editorialized that “government agencies cannot justify discrimination against any group of citizens where public monies, provided by the citizenry as a whole, are being spent.”(65) Amid growing pressure, the Housing Commission finally agreed to a compromise: in its 1741 existing units and 1200 deferred units, the neighborhood pattern policy would be grandfathered in while all new permanent projects would uphold a nondiscrimination policy, housing tenants “in order of application.”(66)

After winning local voter approval in 1950 for construction of new public housing units, the SFHA resumed its building program across San Francisco, continuing segregationist practices as well as efforts to stymie tenant organizing. With whites in four projects and African Americans in one, the SFHA focused on completing additional segregated developments.(67) In 1952, the SFHA opened two deferred projects: Ping Yuen in Chinatown, designated as an all-Chinese project, and North Beach Place in North Beach, opened to white tenants. During the finalization process for both developments, John Beard urged the Housing Commissioners to convert planned meeting spaces into additional apartment units. These spaces, he argued, were costly to maintain and duplicated Parks and Recreation facilities. As news spread about the elimination of community spaces, the San Francisco Housing and Planning Association, Youth Council, and former Housing Commissioner Alice Griffith fought to reclaim the community spaces by demonstrating the importance of these sites for accommodating adult and youth programs.(68) Ultimately, it would be future tenants themselves who would successfully push the Housing Commission to provide communal meeting spaces at Ping Yuen and North Beach Place.

At Ping Yuen, widely celebrated by Chinatown residents and the city, the Housing Authority’s commitment to providing Chinese Americans with modern housing, and segregating them in Chinatown, drew praise. City-dwellers lauded the SFHA for tearing down crowded “tenements” in the district that had San Francisco’s “highest tuberculosis and death rates” and replacing them with projects that attracted tourists with their faux-Chinese architectural style.(69) Containing the Chinese in Chinatown, which Ping Yuen residents themselves readily accepted, did not incite controversy, as when North Beach Place opened a few months later. African-American applicants protested their exclusion from North Beach Place, but not from Ping Yuen, possibly because they did not want to live in Chinatown and would not have been welcomed there.

Although San Francisco took pride in its “history as a multiracial, multiethnic city” that “proved a mixed population could coexist without deadly violence,” African Americans and Chinese Americans in the post-war World II era faced systemic discrimination in housing.(70) A long history of diversity did not result in peaceable integration. It was the exclusion of African Americans from a white housing project, rather than the segregation of Chinese Americans in Chinatown, that intensified criticism about segregation in public housing. The racist system characterized by the black/white binary in the American South and challenged by the growing Civil Rights Movement emerged as a contentious issue at North Beach Place. The NAACP sued the SFHA on behalf of three African-American applicants denied admittance to North Beach Place in 1952. In 1954, the US Supreme Court justices refused to hear the Banks v. Housing Authority of San Francisco case, thus upholding the California Supreme Court ruling against segregation in San Francisco public housing. Despite the court ruling, the SFHA’s consistent practice of segregating African Americans and Chinese Americans aroused controversy and created problems for the agency and some tenants over the next four decades.

Under Beard’s leadership, and against the backdrop of the deepening Cold War, the SFHA as the city’s largest landlord continued its focus on maintaining and controlling public housing.(71) Over its twelve years in operation, the SFHA had housed 173,750 tenants, generated total revenues of $28,607,000, and employed thousands of workers while supporting public and nonprofit services in public housing.(72) Asserting top-down control, Beard had the SFHA hire its own police force and conduct its own surveillance. These measures ensured the SFHA’s tight control over tenants living in public housing while slight tweaks to tenant eligibility requirements continued to determine who future tenants would be. The SFHA prioritized low-income nuclear families headed by “live-in” veterans; preferred citizens; and, after 1952, enforced the federal Gwinn Amendment “requiring public housing tenants to be free of subversive ideas and associations.”(73) At the same time, the agency began to expand eligibility for public housing to the elderly, receiving federal approval in 1954 to construct a housing development solely for seniors. The combination of smaller apartments, which were less expensive to build, and the public perception of the elderly as law-abiding good neighbors, made public housing for seniors an appealing option for the SFHA. The 1956 Housing Act legislated seniors as eligible tenants in government-funded housing. Over time, the SFHA responded to the need for senior housing by setting aside units equipped for elderly tenants in new public housing developments.(74)

In responding to San Franciscans’ need for affordable housing, the SFHA continued to segregate many of its projects under Beard’s leadership. The Supreme Court’s 1954 decision dismantling the neighborhood pattern policy, and the 1962 Executive Order issued by President John F. Kennedy outlawing segregation in all federal housing, had little effect on the SFHA’s actual operations. As the African-American population of San Francisco increased after the war, the Housing Authority looked for ways to discourage black in-migration. In a May 16, 1962 letter to John C. Houlihan, the Mayor of Oakland, the San Francisco Housing Commissioners commended the mayor for his statement on the “Freedom Train” migration and joined him in asking the “Southern States” to discontinue their push for African-American migration to the west. The mayor criticized white southerners for “capitalizing on the misfortune of the Negroes for which the whites themselves are much to be blamed.”(75)

Houlihan also reminded them that the West did not welcome the exodus of African-American migrants: “The City of Oakland and the enlightened people of the West face our own problems, and these people may become one of them. We do not send our problems off to other states.”(76) Limiting the population of African Americans, the Housing Authority seemed to conclude, would perhaps lessen the problem surrounding public housing integration. At the same time that the SFHA voiced concern about the growth of the African-American population in the city, it provided more public housing in Chinatown, opening the 194-unit Ping Yuen Annex in 1962. While the agency claimed to have accepted applicants who were not Chinese, over 97 percent of the tenants were of Chinese descent. The SFHA continued to defend Ping Yuen’s demographics on the grounds that tenants were happy living in a segregated project.(77)

The persistence of segregation in public housing and in the private housing market in California increasingly came under fire as fair housing and civil rights advocates worked for change. Fair housing legislation was critical to ensuring racial integration and became a key piece of civil rights reform. Statewide battles between civil rights advocates and the state and national real estate lobby raged on in the early 1960s. In response to the California Real Estate Associations’ (CREA) planning for a statewide measure to block fair housing legislation, W. Bryan Rumford (Dem., Berkeley) sponsored the California Fair Housing Bill in 1963, which would make racial discrimination in housing illegal. By the time the bill was set for a vote, it made discrimination in public housing and property of more than five units illegal. Governor Brown signed the bill into law in June 1963, but insufficient enforcement made it more of a symbolic victory.(78) Resistance from the real estate industry and segregationists persisted and included the CREA-backed ballot initiative Proposition 14 which would amend the state constitution to legalize housing discrimination.(79) The highly controversial proposal appeared on the ballot in the 1964 election: in an eight-to-seven margin, San Franciscans voted for Proposition 14, while also supporting Lyndon Johnson over Barry Goldwater for President, and approving local measure H authorizing 2500 units of new public housing in the city.(80) Governor Brown reflected on the election returns supporting Proposition 14, stating the “majority of whites in this state just don’t want Negros living in the same neighborhood with them.”(81) In 1966, the California Supreme Court ruled that Proposition 14 was illegal.

President Johnson’s Great Society Programs—the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act, and the Immigration Act of 1965, as well as the creation of Medicare, Medicaid, Legal Aid, Head Start, and the Office of Economic Opportunity—buttressed civil rights supporters in San Francisco and elsewhere and brought much-needed anti- poverty programs to the city. These programs, many promoted by neighborhood-based Economic Opportunity Councils, sought to empower low-income citizens in the social and economic improvement of their communities. The anti-poverty and community action programs, as well as the creation of the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), established to coordinate housing and redevelopment initiatives, factored into ongoing changes in San Francisco public housing over the next decade.

Although many San Franciscans had voted to maintain segregation in the private housing market, citizen pressure for the SFHA to comply with federal mandates to desegregate public housing intensified. Despite the SFHA’s integration of Valencia Gardens, North Beach Place, and a number of other projects after 1954, the NAACP and the United Freedom Movement, a San Francisco off-shoot of the NAACP, nonetheless criticized the agency for not breaking up segregation in all public housing across the city. Civil rights organizations focused their attention on integrating projects that had mostly white or black residents rather than attacking the homogeneity at Ping Yuen. They also condemned the Housing Authority for discriminatory hiring practices. The NAACP and the United Freedom Movement pointed to the lack of black-white integration in public housing and attacked the “racial imbalance” among Authority maintenance workers, blaming the inequity on the SFHA’s practice of “hiring workers from union hiring halls which are operated in such a manner as to foreclose or discourage Negro applicants.”(82) Picketing at Hunters Point and Potrero Terrace and repeatedly marching at the Housing Authority office on Turk Street with signs reading “Discrimination Must Go” and “Hire Apprentices,” the NAACP vocally and publicly pressured the SFHA to change its housing and hiring practices.(83)

The combination of the protests and a 1965 ruling by the California Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC) that found the SFHA “was using various devices to perpetuate the Negroes’ housing and job-getting plight” forced the agency to act. Two months after the FEPC ruling, the commissioners voted to “begin negotiations with a management firm which would look into the Authority’s hiring and rental policies.”(84) The Housing Commission followed the recommendations of the FEPC and took steps “to improve the agency’s public image” by approving a new set of hiring rules “that would give minority groups greater employment opportunities in the agency” and eliminate “references to race in rental applications.”(85) The agency also created a new position, Director of Human Relations and Tenant Services, “to insure that neither housing assignment nor job discrimination is practiced by Housing Authority personnel.”(86)

These changes failed to quell the increasing criticism levied against the agency as a whole, and long-time Executive Director John Beard in particular. As Executive Director of the Housing Authority for twenty-two years, Beard had presided over the agency’s entrenched segregationist policy and practices and had blocked tenant organizing in San Francisco public housing. Despite the 1954 Supreme Court ruling and Kennedy’s Executive Order, he continued to promote segregation in public housing.(87)

Criticized by the NAACP, State Assemblyman John Burton, and the Catholic Interracial Council for failing to integrate public housing, Beard became the target for allegations of discrimination lodged against the SFHA since the 1950s.(88)

Bolstered by the civil rights movement and the emergence of anti-poverty programs in the city that advocated for their active involvement, tenants began to organize and mobilize for change: removing Beard became a priority. After years of systematic repression of tenants’ organizations, public housing residents drew “on the city’s civic culture and history of resistance to capital and authority” to voice their concerns and work for change.(89) From attending and addressing the Commissioners at meetings, to writing newsletters, to demanding better maintenance and services, tenants began exercising their democratic rights, pushing against Beard and decades of attempts to silence them. Following the scathing FEPC findings outlining the SFHA’s failure to administer housing and employment fairly, tenants and community allies joined together to push Beard out. At a packed Housing Commission meeting in October 1965, representatives from four tenants’ associations representing thousands of tenants presented a list of grievances before sharing the microphone with Assemblyman John Burton’s (Dem., San Francisco) assistant who read a telegram from his boss. In the telegram, Burton endorsed the tenants’ organizations, criticized the SFHA for its treatment of tenants, and blamed Beard for running “a third rate operation.”(90) The dramatic changes and dynamism of the decade, coupled with intense scrutiny and criticism of his leadership, eventually led to the end of Beard’s tenure. During an executive session of the Housing Commission in 1965, the commissioners voted to oust Beard. His departure from office, however, did not signal the end of the SFHA’s problems.

Notes

15. Nicholas Bloom, D. Bradford Hunt, Lawrence Vale, Rhonda Y. Williams, and others have documented how the New York Housing Authority, Chicago Housing Authority, Boston Housing Authority, and Baltimore Housing Authority aligned with federal expectations of rigorous review of applicants who wanted to live in public housing in the early years of the program. See Bloom, Public Housing That Worked; D. Bradford Hunt, “Was the 1937 U.S. Housing Act a Pyrrhic Victory?”; Lawrence J. Vale, From the Puritans to the Projects: Public Housing and Public Neighbors (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007); and Williams, The Politics of Public Housing: Black Women’s Struggles Against Urban Inequality (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005). See also Gwendolyn Wright, Building the Dream: A Social History of Housing in America (New York: Pantheon, 1981).

16. Wright, Building the Dream, 230.

17. Ibid.

18. SFHA, Second Annual Report, 20.

19. The specific regulations of the SFHA are not available. However, many local housing authorities followed federally recommended guidelines. The regulations listed in the text were standard at other housing authorities. A tenant who grew up in Valencia Gardens a decade after it opened verified that the SFHA upheld such regulations in San Francisco public housing.

20. “Two-Story Rows and Flats,” Architectural Forum, November 1940, 4. Other press accolades about Holly Courts included a long article, “Holly Courts Has ‘em Agog,” in the April 27, 1940 San Francisco Call Bulletin, about the first tenants at Holly Courts.

21. Brown designed the Department of Labor and Interstate Commerce Commission building in Washington, DC. For more information on Brown’s architectural legacy, see Tilman, Arthur Brown, Jr.

22. According to Arthur Brown, Jr. biographer and scholar Jeffrey T. Tilman, Brown originally planned to build Holly Courts in the French Country style with tiled roofs. Federal restrictions led Brown to change to a modern design with flat roofs. Tilman, interview by author, July 2001. Brown went on to build San Francisco’s domed city hall.

23. According to the SFHA, 55 dwelling units were eliminated through “compulsory demolition, 28 through compulsory closing, 12 through compulsory repair or improvement; and 23 were demolished by private owners after action had been instituted by the department of Public Health” (SFHA, Second Annual Report, 12).

24. Outline of Marshall Dill’s Speech, Marshall Dill Papers, folder 35, North Baker Research Library, The California Historical Society.

25. “Holly Courts: Special Bulletin of the San Francisco Housing Association” (San Francisco: San Francisco Housing Association, 1940), Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. The second quote is from the outline of Marshall Dill’s speech, Marshall Dill papers.

26. SFHA, Second Annual Report, 15.

27. Else Reisner, “Homemaking and Family Adjustment Services in Public Housing: The Experiences at Holly Courts, First Western Housing Project“ (San Francisco: San Francisco Housing Authority, 1942).

28. Reisner, Home Making and Family Adjustment Services, 14-15.

29. SFHA, Second Annual Report, 15.

30. Ibid.

31. SFHA, Third Annual Report, 8. “Movie on Housing is Available to Clubs,” Low Rent Housing News, 7 April 1941, 1.

32. The program, which ran for seventeen consecutive weeks and “received favorable reviews from listeners,” featured actors from the Works Progress Administration (SFHA, Second Annual Report, 24).

33. “’More than Shelter,’ Ready for Showing,” Low Rent Housing News, San Francisco, 16 June 1941, 1, and untitled article in Low Rent Housing News, August 30, 1941, 1. William Abbenseth was a photographer for the Federal Art Project who was well known for his black-and-white photographs of San Francisco architecture.

34. SFHA, Third Annual Report, 3.

35. Lawrence Vale, From the Puritans to the Projects, 3. The admitted families, as Vale outlines, eventually left public housing as they earned more money and housing authorities were forced to begin housing the neediest applicants in cities. By the mid-1950s, changes in federal housing policies undermined the merit system. By the 1970s, the poorest of the poor populated public housing (3, 8).

36. SFHA Commission Minutes, 7 October 1947.

37. Albert S. Broussard, Black San Francisco: The Struggle for Racial Equality in the West, 1900-1954 (Lawrence, Kansas: University of Kansas Press, 1993), 177. In Alien Neighbors, Foreign Friends: Asian Americans, Housing, and the Transformation of Urban California, Charlotte Brooks details the debates over the construction and tenant selection process at Westside Courts. The multiracial, multiethnic Western Addition Housing Council (WAHC), formed in 1940, pushed for public housing in the district that would serve Japanese Americans, African Americans and whites. Ultimately, Japanese American support waned as potential applicants realized that the SFHA head of household requirements barred many of them from public housing. Conservative African American groups fought for a segregated project in the Western Addition while white residents in the area opposed public housing for African Americans in their area (Alien Neighbors, Foreign Friends: Asian Americans, Housing, and the Transformation of Urban California [Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009], 108-11, 141-4).

38. Housing Authority of the City and County of San Francisco, Fifth Annual Report (San Francisco Housing Authority: The Housing Authority, 1943), 5, 7. SFHA Commission Minutes, 14 May 1942. As the United States mobilized for war in 1940, workers living in rural areas migrated to urban areas in search of employment in the defense industries. This migration caused drastic housing shortages in centers of defense activity such as San Francisco. The federal government responded to the housing crisis first by authorizing the USHA to build 20 public housing developments for civilian employers of the armed forces and defense contractors with money originally slated for public housing. When the government’s other efforts to stimulate private industry in home building in centers of defense activity fell through, the government focused solely on federal public housing as a solution to the housing problem. In October 1940, President Roosevelt signed The National Defense Housing Act, also called the Lanham Act, authorizing the Federal Works Agency (FWA) to construct housing for workers in the defense industry who faced severe housing shortages. Representative Fritz Lanham (Democrat, Texas) blocked the potential increase of public housing units after the war by securing an amendment that prohibited defense public housing from being converted to low-income public housing without Congressional approval.“ For more information on the federal housing program during World War II, see Kristin M. Szylvian, “The Federal Housing Program During World War II,” in From the Tenements to the Taylor Homes: In Search of an Urban Housing Policy in Twentieth Century America, ed. John F. Bauman, Roger Biles, and Kristin M. Szylvian (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000), 121-122. The description of where war workers lived is from Marilyn Johnson, “Urban Arsenals: War Housing and Social Change in Richmond and Oakland, California, 1941-1945,” Pacific Historical Review 60, no. 3 (1991): 283-308, cited in Baranski, “Making Public Housing,” 143-44.

39. Baranski, “Making Public Housing,” 157.

40. San Francisco Housing Authority, Seventh Annual Report (San Francisco: Flores Press, 1945), 4-5.

41. Albert Broussard, Black San Francisco, 175. African American tenants in SFHA housing had a markedly different living environment than other black in-migrants housed in the city. Prior to World War II, the city had not enacted racial covenants against the small population of 5000 African Americans living in San Francisco. The dramatic increase in the black population during World War II, however, sparked wide- spread discrimination in housing. As a result, a number of tenants lived in overcrowded, rat-infested buildings in the Fillmore district where a 1944 survey found some residents living with 9 to 15 others in a single room. Many of the dwellings did not have hot water, bathroom facilities, or enough windows to provide access to natural light. Along with suffering distressing living conditions, African American migrants also paid higher rents for substandard dwellings than black non-migrants and non- migrant Chinese Americans (172-175). Broussard points out that blacks also occupied a “disproportionate share of the Western Addition’s substandard housing relative to the city’s population” (173). For more information on housing discrimination in San Francisco, see Deirdre Sullivan, “Letting Down the Bars: Race, Space, and Democracy in San Francisco, 1936-1964” (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 2003).

42. Photograph caption, San Francisco Housing News, August 1944. The caption describes the children as “two patients . . . who have achieved national fame.” According to the SFHA, the photograph prompted people “from all parts of the world” to write letters responding favorably to it (SFHA, Seventh Annual Report, 15). The SFHA’s wartime activities extended beyond overseeing a massive building program for the federal government. Along with the construction and management of temporary war housing, the SFHA set up emergency accommodations for hundreds of sea bound servicemen on the Saratoga when the ship secretly underwent repairs in San Francisco. Additionally, at the close of the war, the agency provided housing for more than 1000 former Allied prisoners from 29 nations pending return to their homes. San Francisco Housing Authority, Golden Anniversary Report, 1987, 4. In a final act of wartime service, the SFHA housed 1200 Nisei, second generation Japanese Americans, many of whom lost their homes and land during their war internment. San Francisco Housing Authority, Twenty-fifth Annual Report (San Francisco: The Housing Authority, 1963), 3.

43. SFHA Commission Minutes, 14 May 1942.

44. Griffith’s objection to discrimination quoted in Baranski, “Making Public Housing,” 124. SFHA Commission Minutes, 14 May 1942. The first part of the resolution stated that “in the development of its program and the selection of its tenants this Authority shall provide housing accommodations for all races in proportion with the numbers of low income families otherwise unable to obtain decent, safe, and sanitary dwellings in each racial group, bears to one another.”

45. Wilder left his post as Executive Director of the SFHA to become the director of Public Works of San Francisco. According to Alice Griffith, Evers had “gained experience in governmental procedure in the Federal Housing Administration” and together with John Bakewell, Jr., Frederick Meyer, and Warren Perry had surveyed slum areas in the city and developed a plan for clearing 8 blocks in the Hayes Valley district and building housing for low-income families. The plan was submitted to the Federal Public Works Administration and approved but did not obtain grant funds due to timing (Griffith, “A Review of the Proceedings,” 3).

46. Baranski, “Making Public Housing,” 175.

47. Quote from Baranski, “Making Public Housing,” 176; SFHA Commission Minutes, 18 August 1943; San Francisco Housing Chronicle, 19 October 1943; and Alice Griffith, “A Review of the Proceedings.”

48. Baranski, “Making Public Housing,” 178.

49. Ibid., 184.

50. Ibid., 185. Quote in Mourice E. Harrison, “Report of the Mayor’s Committee on Civic Unity of San Francisco,” 15 March 1945, Folder 377, Box 97-19, Stewart-Flippin Papers, MSRC, cited in Baranski, “Making Public Housing,” 184.

51. From Civic Unity Committee, Meeting Notes, Folders 376-81, Box 97-17, Stewart- Flippin Papers, MSRC, cited in Baranski, “Making Public Housing,” 186.

52. Baranski, “Making Public Housing,” 186.

53. Ibid., 187.

54. Ibid., 188; Baranski is citing “Questions and Answers, “17 January 1945, Folder 377, Box 97-19, Stewart-Flippin Papers, MSRC.

55. SFHA Commission Minutes, 15 November 1945.

56. Ibid.

57. SFHA Minutes, 18 April 1946, quoted in Baranski, “Making Public Housing,” 193.

58. Mary Shepardson, “Minority Groups,” San Francisco Public Housing: A Citizen’s Survey (San Francisco: San Francisco Planning and Housing Association, 1946), 21.

59. SFHA Commission Minutes, 18 April 1946; Broussard, Black San Francisco, 182. Dr. William McKinley Thomas migrated to San Francisco after serving as a doctor in the army and was part of the growing number of black professionals in the city actively engaged in civic life. Thomas actively opposed segregation in San Francisco public housing. In what Albert Brossard describes as a departure from “protocol that was characteristic of commissioners,” Thomas publicly criticized chairman E. N. Ayer and went on to offer a motion opposing segregation in the SFHA’s public housing developments. His motion was dropped after failing to receive a second (Broussard, Black San Francisco, 222-23).

60. Catherine Bauer praised Marin County’s housing authority for making strides to integrate tenants. In a letter to Ed Weeks at Atlantic Monthly, Bauer praised Marin City’s efforts as “a model of community cooperation and morale in war housing.” Catherine Bauer to Edward Weeks, editor Atlantic Monthly 13 May 1945, Folder 5, Box 2 Catherine Bauer Wurster Papers, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, cited in Baranski, “Making Public Housing,” 194.

61. SFHA, Road to the Golden Age, 12.

62. The Housing Act of 1949 marked the entrée of the federal government into local city building projects. The act, supported by a unique coalition of trade unions, real estate interests, lenders, farmers, and housing advocates, set forth 5 titles to reach its goal, 3 of which drastically altered American cities. Title I financed slum clearance under urban “redevelopment” stating that a municipality could redevelop any “substandard” neighborhood and the federal government would cover two-thirds of the costs. Title II increased authorization of FHA mortgages and Title III promised 810,000 units of public housing by 1955. Collectively this legislation, as implemented by cities across the United States, reshaped urban centers and the suburbs. As the FHA provided mortgage insurance to middle-class Americans moving to the suburbs, cities demolished large tracts of affordable housing with federal redevelopment funds. The act stipulated that local governments awarded funds clear “substandard dwellings” and replace them with “predominantly residential” structures. Consequently, low-income neighborhoods gave way to office buildings, shops, parking lots, and luxury apartments that city leaders hoped would reinvigorate the tax base. See Robert E. Lang and Rebecca R. Sohmer, eds. “Legacy of the Housing Act of 1949: The Past, Present, and Future of Federal Housing and Urban Policy” Housing Policy Debate 11 no. 2 (2000): 291-98, and Roger Biles, “Public Housing and Postwar Renaissance, 1949-1973,” in From Tenements to the Taylor Homes: In Search of an Urban Housing Policy in the Twentieth Century, ed. John F. Bauman, Roger Biles, and Kristin M. Szylvian (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000), 143-162.

63. Chester Hartman, with Sarah Carnochan, City for Sale: The Transformation of San Francisco (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 15-16. City for Sale includes an exhaustive analysis of the redevelopment agenda and the Yerba Buena Center controversy in San Francisco.

64. Baranski, “Making Public Housing,” 231.

65. Quote from San Francisco News, 14 February 1950 cited in Baranski, “Making Public Housing,” 233.

66. San Francisco Chronicle, 21 February 1950, cited in Baranski, “Making Public Housing,” 234.

67. The SFHA classified Latino/as as white in their records. I do not have information on when Latino/as moved into “white” projects. The Chinese were classified as “non-white.” A fire at the SFHA in the 1960s destroyed a number of documents, including perhaps some demographic information. In untangling the racial and ethnic make-up of the agency’s projects, it is important to note that the SFHA classified Latino/as as “white.” More recent demographics obtained by the SFHA show the following percentages for heads of household in public housing in 1999: Asians made up 26.45%; Blacks 46.19%; Hispanics 8.70%; Native Americans .45%; Other 3.07%; and Whites 15.09% for a total of 99.95%. Although I was given data on 2013 demographics I was told it might be inaccurate. Email from Florence Cheng, SFHA, April 2013.

68. Baranski, “Making Public Housing,” 220-21. The advocates wrote letters, met with the Commissioners and Beard, and researched how tenants used community rooms in other SFHA public housing projects. Their report stated that in the last half of 1949, 200,000 people had attended lectures, programs, events, etc.

69. “Worst in U.S.” San Francisco Chronicle, 1 July 1949.

70. Sullivan, “Letting Down the Bars,” viii.

71. For broader context on the Cold War’s impact on civil rights debates nationally, see Martha Biondi, To Stand and Fight: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Postwar New York City (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003); Thomas Borstelmann, The Cold War and the Color Line: American Race Relations in the Global Arena (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001); and Roger Daniels, Guarding the Golden Door: American Immigration Policy and Immigrants Since 1882 (New York: Hill and Wang, 2004).

72. San Francisco Chronicle, 20 April 1951, cited in Baranski, “Making Public Housing,” 222. The SFHA returned its profit to the federal government and paid the city $2,631,000 in lieu of taxes.

73. Baranski, “Making Public Housing,” 227. According to the SFHA Commission Minutes of June 19,1952, the SFHA “hereby prohibited as a tenant of any project, by rental or occupancy any person other than a CITIZEN of the United States, except that such prohibition does not apply in the case of the family of any serviceman or the family of any veteran who has been discharged (other than dishonorably) from of the family of any serviceman who dies in the armed forces of the US within 4 years prior to the date of application to such project. The term “tenant” means the responsible member of the family who signs the dwelling lease.”

74. For example, the Yerba Buena annex, opened in 1961, had 211 units with 43 units set aside for elderly. Likewise, the Ping Yuen Annex, opened the same year, offered 44 units of senior housing.

75. C. R. Greenstone, Chairman, San Francisco Housing Authority to John C. Houlihan, Mayor of Oakland, California, 16 May 1962, copy in SFHA Commission Minutes, May 1962.

76. Ibid.

77. SFHA Commission Minutes, February 1962-March 1963.

78. Baranski, “Making Public Housing,” 284.

79. For more on white conservative backlash against the civil rights movement and the impact on housing, see Matthew Countryman, Up South: Civil Rights and Black Power in Philadelphia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006); Kevin M. Kruse, White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005); and Matthew D. Lassiter, The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics in the Sunbelt South (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006).

80. Baranski, “Making Public Housing,” 285-98.

81. San Francisco Chronicle, 11 November 1964, cited in Baranski, “Making Public Housing,” 300.

82. “Housing Authority Job Bias Charged,” San Francisco Chronicle, 13 May 1964.

83. “Picketing at Turk St. Housing Authority,” San Francisco Chronicle, 19 March 1965. See also “Housing Chairman Swings at Critics,” San Francisco Chronicle, 19 February 1965, and “An Orderly Protest on S.F. Housing,” San Francisco Chronicle, 20 February 1965. NAACP leaders met with Mayor John Shelley to express their concerns over the SFHA’s discriminatory hiring practices and placement of tenants in housing projects.

84. Peter Kuehl, “Getting the Picture,” San Francisco Chronicle, 16 April 1965.

85. Jack Lind, “Housing Board’s New Rights Rules,” San Francisco Chronicle, 2 July 1965.

86. “Housing Authority Aide Named,” San Francisco Chronicle, 3 April 1964. The Housing Authority created the position in 1964 in an early attempt to quell criticism. Nonetheless, the United Freedom Movement lambasted the agency for failing to consult their group when writing the job description. The United Freedom Movement, an African American rights organization, had lobbied the SFHA to create the post in 1963. ”Flare Up Over Human Relations Post,” San Francisco Chronicle, 20 March 1964.

87. “John Burton Blasts S.F. Housing Boss,” San Francisco Chronicle, 8 October 1965.

88. A survey by an outside management firm described Beard as a leader who bypassed the housing commissioners and set his own policy (“John Burton Blasts S.F. Housing Boss,” San Francisco Chronicle, 8 October 1965).

89. John Baranski, “‘Something To Help Themselves: Tenant Organizing in San Francisco Public Housing, 1965-75,” Journal of Urban History, 33, no. 3 (March 2007), 424. See also Frederick Wirk, Power in the City: Decision Making in San Francisco (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974); Hartman, City for Sale; Judy Yung, Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995); Broussard, Black San Francisco; and James Brook, Chris Carlsson, and Nancy Peters, Reclaiming San Francisco: History, Politics, and Culture (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1998).

90. Baranski, “Something to Help Themselves,” 420.

Excerpted from More than Shelter: Activism and Community in San Francisco Public Housing by Amy L. Howard. Used by permission of the University of Minnesota Press. © Copyright 2014 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota. All rights reserved.