Frisco Bay Mussel Group: Living Here

Primary Source

This text is from a small pamphlet published in 1977 by the Frisco Bay Mussel Group. At the end of the pamphlet a brief description was presented:

The Frisco Bay Mussel Group is a “committee of correspondence” to act as a forum for sharing regional identity and watershed consciousness. There is no city/country division within the group because both locales are essentially interrelated through and encompassed by the San Francisco Bay-Sacramento River Estuary watershed. But there is a spirit to alter the dominance of city demands on the region and extend a sense of regionhood to everyone living within it. Rather than restricting itself to areas such as ecology, environment or conservation—which appear to be directly related but tend to divorce the full activity of human lives from other natural processes, the Mussel Group is developing information about:

- • native inhabitants, small self-sufficient early homesteaders, new settlers

- • the extent of the watershed: biotic and life-realm characteristics—geology, climate, plants & animals

- • priorities for restoring natural systems & removing exploitation threats

- • manufacturing and agriculture justified by non-exhaustive use of labor and renewable soil, energy and materials within in the region

- • the spirit of multi-species relationships within the region and ceremonies to ensure biotic richness and diversity

- • partnership and trade within the watershed and with other distinct regions

- • a form of planet-wide regional address

This Watershed Guide was published together with the pamphlet "Living Here" that is republished below.

Living Here

Borne-Native In the San Francisco Bay Region

We who live around the San Francisco Bay-Sacramento River Estuary, all species ranging this watershed on the North Pacific Rim, feel a common resonance behind the quick beats of our separate lives; long-pulse rhythms of the region pronouncing itself through Winter-wet & Summer-dry, Something-flowering-anytime, Cool Fog, Tremor and Slide.

The region proclaims itself clearly. It declares the space for holding our own distinct celebrations: Whale Migration & Salmon Run, Acorn Fall, Blackberry & Manzanita Fruit, Fawn Drop, Red Tide; processions and feasts which invite many other species, upon which many other species depend. The bay-river watershed carries these out pouring easily. They are borne, native, by the place. Their occurrence and the full life of the region are inseparable.

Human Beings have lived here a long time. For thousands of years, the region held their celebrations easily. They ate enormous quantities of shellfish, acorns, salmon, berries, deer, buckeyes, grass seeds and duck eggs. They cut countless tule reeds for mats, boats and baskets, burned over thousands of acres of dead grass, made trails everywhere, cleared land and packed down soil with villages. They netted fish from boats, strung fish traps across creeks and rivers, and dug up tidelands looking for clams and oysters. The region probably never held a species that had a greater effect upon it, but for thousands of years human beings were part of its continuous life. They lived directly in it, native.

The Shell Mound Cultures & the Ancient Kuksu Cult

Over four hundred shell mounds have been found in and around the Bay Area, and many of these mounds date back into the third, even the fourth millennium before the present. The mounds were for the most part composed of oyster, clam, and mussel shells. But animal and fish remains also provide us with a pretty good idea of both the wildlife of the Bay Area during these early days, as well as the hunting and fishing practices of the first inhabitants. Deer, Elk, Sea Otter, Beaver, Squirrel, Rabbit, Gopher, Raccoon, Wild Cat, Wolf, Bear, Dog, Seal, Sea Lion, Whale, Porpoise, Canvasback Duck, Goose, Cormorant, Turtle, Skates, Thornbacks and other fish were all found within the mounds. They also contained the remains of some of the first settlers, and occasionally male bodies were found accompanied by pipes and weapons, and female bodies were found with mortar, pestle, and awls. The large number of these mounds, as well as the range of artifacts, gives us some idea of the size and sophistication of this early culture. Along with a number of fishing and hunting tools and utensils, highly polished stone awls, graceful “charm stones,” delicately worked stone pipes, bone whistles, labrets, and certain shell beads and pendants were also found in the debris.

The appearance of this Shell Mound Culture in the Bay Area during the fourth millennium before the present can perhaps best be understood in terms of the larger movements of people going on throughout the entire Pacific Basin and upon the Pacific Rim during this period of history, a period when sedentary fishing peoples began to experiment with fish poisons and food resources (the mound itself being an excellent open air “lab”) thus leading to the invention of the cultivated crop and agriculture.

The largest shell mound in the Bay Area was found at Emeryville, and it was quite well known as the site of the Emeryville Shell Mound Park at the turn of the century. The mound was destroyed, and the main plant of the Sherman Williams Paint Company—“We cover the Earth”—was built on its spot in 1923. This mound was quite large—200 feet long, over 25 feet high, and over 50 feet wide—and visitors would note how, sharing certain seasons, it was constructed to take full advantage of the sun setting directly between the narrows of the Golden Gate straits. The area is characterized today (coincidentally?) by a series of anonymous, brilliant wooden sculptures that have been raised on the land-fill areas adjoining the old park and the re-inhabitation of many of the abandoned industrial warehouses of Emeryville by artists, crafts people and small press publishers in and around Shell Mound Road.

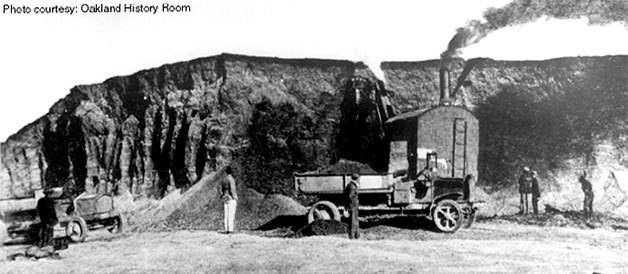

Demolition of the Emeryville shellmound in 1924.

Image: Phoebe Hearst Museum of Anthropology #15-7792

Demolition of the Emeryville shellmound.

Photo: Oakland History Room, Oakland Public Library

Although the Costanoan Indians may or may not have been the people who constructed these mounds, by the time of Spanish colonization the Costanoan people had occupied all the old mound areas of the East Bay and the San Francisco peninsula south to Monterey, while the Coast Miwok peoples occupied Marin to the north. Clearly by the time of European contact, the Sacramento River had become the key to the Indian geography of the Bay Area and to follow the river inland was to come in contact with increasingly populous and sophisticated culture. Of the many fascinating Indian cultures occupying the inland foothills and the Valley, the Pomo peoples—perhaps the most respected basket weavers in the New World—deserve special mention. The Pomo people in and around Clear Lake which can be seen as the “capitol district” for north central Indian culture seem to have had the greatest impact on the area’s Indian culture as a whole. In contrast to the Pomo way of life which has been documented, precious little is known about the Costanoan peoples who lived on the Bay. We do know that at the time of contact at least as many as 21,000 Costanoan Indians were living in this area, with another 4,000 Coastal Miwok living in Marin. The Indian population for the Sacramento River Watershed area, moreover, was well over 140,000 people. By 1910, after less than two hundred years of disease and mistreatment introduced by the invaders, the Costanoan and Coastal Miwok cultures had been completely wiped out. And only 2,800 natives were still living in the greater Sacramento Watershed area—and most of them were living as far away from the center of colonial activity and civilization as they could. Visions of Gold, both Yankee and Conquistador, seem to have been the central agency of destruction.

The few reports of Costanoan culture that survive are uniformly unflattering and tell us more about the mind of the invader than they do about the fact of native culture. There is a bittersweet irony to these reports, a black humor that sounds at times as if the script had been written by Lenny Bruce. Consider this description of Jose Espinosa y Tello on the Costanoans of Monterey. “Men and women go naked feeding in the fields like brute beasts or gathering seeds for the winter and engaging also in hunting and fishing. Although some of these natives have now been reduced to obedience (italics added) and form part of the Mission of San Carlos, they still preserve their former disposition & customs. Among other habits which they retain it has been noticed that in their leisure moments they will lie on the ground face downwards for whole hours with the greatest content.” Clearly the Costanoans were the subject of vicious and unfair reporting, as were, of course, most of the Indians of North America. The anthropologist Kroeber, who accepts most of these reports at face value, tells us the Costanoans were a ‘dark, dirty, squalid and apathetic’ people. “I have never seen one laugh.” He reports one invader, Choris, as saying “I have never seen one look you in the face.” Nonetheless, reading between the lines, certain details do emerge, and these details suggest a very different portrait of these people. “Costanoan, from the Spanish, meaning a coastal people . . . Coyote, Eagle, Hummingbird sitting on a mountain top. When the ocean receded and the land appeared, it was Coyote who went down & created these coastal people . . . They held the Sun, and the Redwood Tree, as Sacred . . . Sophisticated tule huts, sophisticated tule rafts . . : A line survives from one of their dances—“ We dance on the brink of the World.”

Very little is known about the Costanoan religion. We are told only that at the Mission San Jose the natives continued to hold their ancient winter solstice dance much to the chagrin of the officials. The existence of this dance among the Costanoans suggests that they were influenced by the famous Kuksa Cult, a widespread system of religious belief that served to unite many of the cultures of the Sacramento Watershed area. The Kuksa Cult involved dance rituals and festivals, although it was primarily male-oriented (in counter-distinction to the ancient, female-oriented ghost religion and secret societies), the degree of sexual exclusivity varied from tribe to tribe, clan to clan. The secret Kuksu initiation ceremony conveyed moral, ethical and sacred teachings, and served to inform the initiates as to their place within the circle of all beings.

The Kuksa was always depicted as a terrifying figure, half man and half bird. Consider this description by Jamie du Angulo of the arrival of the Kuksa during the Winter Solstice Festivals among the Pomo. “Finally, just as the last rays of the sun were setting on the western shore of the lake, an extraordinary series of screams and yells started up again—but this time it was coming from the hills. With great excitement the people began to point toward the West. Off in the distance you could vaguely make out the outline of an old, dead tree. An owl was sitting on the top branch of the tree, and a man . . . or a bird . . .was hanging upside down, arms and legs spread stiff and still, from one of the bottom branches. He had feathers, lots of feathers growing out of the top of his head at various angles. Suddenly a fire shot up from the ground underneath him, and he was surrounded by smoke. When the smoke cleared, the man . . . or bird . . . whatever it was . . . had disappeared. ‘That was the Kuksu, Old Man Turtle said, ‘The Kuksu has returned.’”

It is not known when the Kuksu Cult first entered into this area, but the point of origin is thought to have been from the Southwest. Indeed the iconography of the Kuksu Cult—fire, owl, feathers, dead tree—has much in common with similar cults throughout the larger U to-Aztecan cultural area, and the Kuksu himself seems at least in some distant sense related to the great Aztec cult figure, Quetzalcoatl.

The appearance of the Kuksu always followed the ceremony held for the ghosts of the people who had died during the previous year. After the ghosts had been given their sendoff, on the last day of the festival, just at sunset, the Kuksu would arrive, his head ablaze with feathers of many different cultures, a blaze equal to the rays of the setting sun, signifying (seemingly) that a new season and a new Sun had begun its cycle. The arrival of the Kuksu—with its strange high-pitched whistle; his head, torso and limbs all moving to the inaudible sound of three distinct and seemingly unrelated rhythms; and his bird’s headdress an incredible shock of multi-colored feathers sticking out at various and seemingly random angles—the arrival of the Kuksu was the most important and powerful moment of the year.

The Kuksu Cult therefore, certainly began as a Sun Cult of some order, but a Sun Cult that penetrated into an area where the old Pleistocene Religion of the Dead and Ghosts Cults were widely practiced. Indeed the Kuksu Cult in this area is often considered to be a Moon Cult too, as the native Indians held the Moon to be the night-time sun. Hence the Kuksu Cult derived additional power and was to an extent transformed by its close association with the older religion, and it came to have a central synthesizing impact on all the early Indian cultures of this area.

A few hundred years ago some new people moved in and began to impose a non-native way of life over the entire watershed. Instead of living directly in it, they began living from it, on top of it. Dams, canals, pipelines were built to shift “surplus” water away from life systems in rivers, creeks, lakes, and marshes which had always required it. Oysters and clams were stripped from the bay shore within a few years and their beds filled with garbage and crushed hillsides to create waterfront real estate. Within a short time, redwoods and fir forests became houses and San Francisco Bay turned into a huge toilet for sewage and factory wastes. Generations born here called themselves “natives” but kept pushing the watershed’s life to exhaustion. Nearly all habitats for native species were destroyed. Attempts by many species to maintain themselves were stopped through outright slaughter or intolerable despoliation. Some of the largest are lost to the region now; tule elk, grizzly bear, condors.

It was extremely profitable for a few of the new people to live here this way. Anything could be seen as an unused surplus by a non-native eye, and it was easy to find markets elsewhere for much of it. But profits began slipping as native life-forms vanished. The place withered quickly and became increasingly less livable for all the people in it.

Watershed

San Francisco Bay is the lower end of a vast watershed, beginning at the highest ridges of the Sierra Nevada and the inner Coast Range, continuing through the Central Valley, and ending at Golden Gate. Watershed is the peak experience: selecting among bodies of water, water divides rainfall/runoff by direction, this rainwater to the Russian River, this to the Bay and Delta, this to the Pacific Ocean.

Watershed often divides plants, animal lives, far-off views—which watershed are you in now? Once divided, water flows in and out of steep mountain canyons, through flat valleys, into marshy, muddy bays and estuaries, always downhill, getting increasingly salty past the Sacramento-San Joaquin River confluence near Antioch, until it becomes one with the ocean in the Bay.

Watershed is a whole, defines what is upriver/downriver, what the space is we roam in, in our own bodies of water. Watershed is the universe of our water body experience. When you follow a watershed, it teaches, leads you on in. When you cut a watershed with roads, dams, and ditches, it bleeds, erodes, floods. Watershed defines place, wind, food, pathways, ceremonies, and chants. Enter into that flowing moment of watershed living, in this place, celebrate the return of salmon and herring, dream of waters merging, enlarge the watershed with your own self, until you are in it totally, until you are it.

Watershed is a living organism: rivers and streams and underground flows are veins and arteries; marshes are the pollution-removing kidneys; water to drink; water is the cosmic sense organ of the earth, the dimpled skin between above and below; water rhythms show us moon, season, shape, and sense of land.

Flowing, tumbling water wears away hard granite, soft sandstone, creates the watershed form with what remains, brings forth nutriment for ocean creatures, creates beautiful beaches, the sound of the river turning is a low moan, waterfalls, roar, water over rocks.

Watershed landscape has history: we build where it’s flat, avoid floods, water the crops, hunt animals at the dark waterhole.

The mud flats around the Bay come from 19th century Sierra Nevada hydraulic mining clay sediments. Flood control dams and channelized streams come from reactions to the 1955 Northern California floods. Disturbances of the river spread upstream as well as downstream; too much silt means no salmon spawning, no clarity for fishing, flooding at the raised river mouth.

Water falls by gravity, rises by levity.

We climb the watershed, to the ridge top, to glimpse what lies beyond, what we can see, well-grounded along the ridge, but intrigued, curious as all mammals are, to see, to see what lies beyond our sight, beyond sense perception?

Down inside the watershed, a few peaks draw our attention: Mt. Hamilton in the south Bay; wind-clean San Bruno Mountain to the west, the wooded sides of Mount Tamalpais in the central and south Bay, the spread-out devil of Mt. Diablo uplifted from the sea to the east, the volcanic lava cap of Mount St. Helena, the highest sliding in and out of view as we travel the lower Russian River watershed. From inside our Pleistocene-drowned Bay valley, we need climb only a short way to rise high enough to see for fifty miles: Ohlone and Miwok Indians watched each other’s fires across the Bay at night, kept an eye on fishing and shellmound rubbish heaps during the day, eyes up on circling hawks.

Water and plants, land and animals are at home, a living whole, an ecosystem in a biotic region. When the water system is cut or altered, all else is affected. When plants are destroyed, land covered for urbanity, water becomes sluggish then ravages towns in floods, dries up creeks in summer, goes underground when overused.

So much of the healthy plant and animal life in our watershed region has been damaged or destroyed, we will need generations to restore it, to return the original healthy native/wild ecosystem to make our peace with this water body.

All around the Bay, there are tens of thousands of acres of diked-off tidelands which could be restored to pickleweed/cordgrass marshland, the planet’s intense biologically productive habitat, where the edge of the sea transfers food from land to water creatures.

Damming all creeks for flood control has been our constant practice, this great fear and unwillingness to live with watershed events. Now these creeks, water courses through the land, wider, deeper, drier than before, need rehabilitation to make them able-bodied again, released from bonds of concrete and riprap. To restore all creeks, to make them flow full of power working for us and all wildlife, is our right work, is right action.

When forests are transformed into housing developments, there is an illusion of prosperity which masks the hollowness felt by people who live in them. Landscapes full of buildings become depressing. Jobs that require annihilating living things or manufacturing monotonous garbage breed self-contempt. Constant exposure to other people or television without an opening to the naturally evolved graces of the planet is oppressive and demeaning. There is a feeling that one’s life is being used, Used up.

Non-native culture, live-in colonialism becomes its own worst threat. Rejection of living within the boundaries of natural life-systems requires mammoth amounts of labor and energy to build, rebuild, and keep-up artificial ones. By reducing the diversity of life in the region, non-native culture constantly narrows opportunities for social and personal self-preservation. There’s a steady movement through extinction of native life towards self-extinction.

Species: Familiar and Ghost

The uniqueness of each place comes in part from ecology and climate, but even more from the biota, the animals and plants that live there, shaping the landscape, its character, and one another as they evolve together. Each species which forms a strand of a living community has its own history and has entered the regional fabric at some point in geological time, bringing the mysterious information of its own previous being.

This subtle and deeply resonant wisdom of place deserves respect and reverence, for those who thoughtlessly destroy information so long in the gathering are guilty of a crime against consciousness. The shrines where uniqueness and subtlety are concentrated should not heedlessly be plowed or paved over. The dappled carpets of Stipa bunchgrass, constellation with shooting stars and Fritillaria the solitary digger bees and dancing Hydropsyche are not replaceable by crude expanses of opportunistic weeds, wild oats & thistles & houseflies, and Argentine ants.

Two hundred years ago San Francisco Bay and the land rimming it was a natural paradise. Nutrients washed down from the mountain slopes all around the great Central Valley, were carried to and accumulated in the Bay, which abounded with fish & oysters, harbor seals, sea otters and dolphins. Indian villages were more numerous along its shores than anywhere else in California. The rich alluvial deposits of the tidal flats were crowned with vast marshes a magnet for awesome hordes of great masses of migratory ducks and geese and also a great food producer for the Bay’s water creatures, while landward grew lush meadows of bunch grass where thousands of tule elk grazed.

In the sand dunes now overlain by the sod of Golden Gate Park, grizzle bears dug out ground squirrels among the yellow lupines and dune tansies. The tule elk and grizzlies are long gone now and the dune tansy is making a last precarious stand on a few small scrapes of land soon to be built upon near the ocean beach. Two small but lovely species of butterflies, which once hovered over the flowering vales of San Francisco and nowhere else, have winked out forever, one in the last century, one in this. The beautiful San Francisco garter snake which lived in little fault ponds along the San Andreas has been seldom seen since developers destroyed most of its habitat in the early 1900s. A marvelous web of native plants and insects, some found nowhere else, still survives on the ridge and upper slopes of San Bruno Mountain, but development plans are closing in fast.

The sea otters have been hunted from the Bay and most of the dolphins and harbor seals are gone. Some of the Bay’s invertebrates, native shrimps and mussels are being crowded out by competing species brought inadvertently from distant seas on the hulls of ships.

In Lake Merced, an estuary which gradually became fresh thousands of years ago, there are freshwater opossum shrimp and tentacled sea worms. Both have so far been able to survive the vagaries of managing the lake for trout fishing.

Golden eagles nested commonly along the East Bay hills and hunted jack rabbits on the flatlands below. A few remain, reminders of the time when they and the great California condors wheeled high in the skies over San Francisco Bay.

The natural communities which persist are precious fragmented holograms of the once great San Francisco ecosystem. We should protect it and as much as possible restore it, for these living roots which penetrate far into the past not only maintain the biological integrity of our home region but nourish our spirit and sense of place as well.

Winter-wet & Summer-dry. Something flowering anytime, Cool Fog, Tremor & Slide will remain. The region’s unique resonance will continue to sound behind whatever celebrations are carried by it and proclaim itself more clearly than any declaration about it. Reinhabitants of the place, people who want to maintain a full life for themselves and for the watershed, are shaping human celebrations that respond to that resonance. Celebrations which depend on but can be shared by other species. Lives which can be part of the region proclaiming itself.

Sharing Water

Recycling wastewater started with McClaren’s vision of Golden Gate Park. Since 1932, Golden Gate Park has been irrigated by reclaimed “wastewater” and people have boated on lakes partly filled from the drains and faucets of the Richmond-Sunset District.

About 1,000 million gallons of fresh water are used each day in the Bay Area. 750 million gallons are flushed and drained into the Bay as “wastewater”. (Each toilet indicates an “outfall pipe”—a pipe that dumps home and industrial “wastewater” into the Bay.) Only 3% (about 26 million gallons) of this “wastewater” is recycled or re-used. The consequences of dumping so much “wastewater” into the Bay have been the contamination of our oceanic food supplies like mussels and the death of many animal and plant species. To heal our bodies and our minds, feces should be put back on the land as fertilizer for food to feed the cities that produces the feces. “Wastewater” should be used to grow the crops, to return strong flows to dammed streams, to slow down the salting of farmlands, and to supplement urban needs that don’t require fresh water (fire protection, street cleaning, park lakes). Recycling sewage water means no new dams, more wild rivers, decreased dependence on petroleum-based fertilizers and restoration of local Bay food production and food-based jobs.

The olive brown California Clapper Rail lives on the mudflats and sloughs probing for mussels, clams, and frogs. Its home is in Cord Grass—the most important grain crop of Bay Area Indians. During the Gold Rush, thousands were eaten by miners and panners. In San Francisco the California Clapper Rail was an elegant entrée—served with local wild rice. Today, of course, the California Clapper Rail faces extinction. Not only the destruction of Cord Grass and marshland but the millions of gallons of industrial pollutants have wiped out or poisoned its (our) food supply. The Clapper is the Bay and Delta’s great environmental applause meter. The more humans control pollution, the more we shall hear the Clapper’s spring song (keck, keck-keck, keck-keck-keck…) A sound like two wood blocks beginning a Latin beat.

The Salt Marsh Harvest Mouse survives or dies out in rhythm with local food-based, economy. Now, with 80% of the original Bay Area Marsh filled for residential and industrial development, the Salt Marsh Harvest Mouse is an endangered species. And, in rhythm with its population, 90% of the Bay’s shellfish area has disappeared. (Shellfish have more protein than beef.) The tiny, salt marsh mouse is rich brown or blackish cinnamon with rust-colored belly. It evolved only in the marshes of the Bay and Delta. Known for its non-aggressive lifestyle, this rodent lives in song sparrow nests to escape the tides and enters a state of suspended animation whenever it’s chilly. The Salt Mouse is our totem animal. Restoring its home, protecting its garden from dredging and filling means restoring our nearby food sources and making paradise the place where you live.

Every bioregion has its plants and animals that live so intimately with the region’s soils and climate that they become symbolic (Totems) of the watershed’s uniqueness. Western Leatherwood is found only on moist hills around the San Francisco Bay. It is both rare and beautiful, its bright yellow flowers appearing around January (the Moon of Leatherwood).

Special soils mean special plants. The sand hills of Felton, the serpentine outcrops of sacred mountains like Mount Helena, the ridge top of Ring Mtn. near Tiburon, the vernal (spring) pools of Sonoma and Solano—all these are the safe-deposit boxes of the Bay’s watershed, keeping and holding the diversity of species for a time when humans and nature can work out a new harmony. These are the homes of special manzanitas and wallflowers and the few native grasses that can still be found.

The Roosevelt Elk’s most southern habitat was the Marin Peninsula. In 1846, a herd of 400 was counted in Pt. Reyes. By 1870, the Elk were hunted out of Marin/Sonoma. Now in 1976, there are plans to re-introduce the Roosevelt Elk into Marin. We can help encourage the Federal Government to protect and maintain “wilderness” area in the Seashore. A place to walk as the Miwok walked is the true recreation of California. Not the “recreation” cluttered with cars, roads, and drive-in campsites.

The family farm is an endangered species. Developers eat up farms for suburban sprawl. The Feds buy out family farms for recreation. Food must travel longer distances to get to the Bay Area and prices go up. Keeping family farms means better nutrition, closer by. It means that our kids can see cows milked, sheep auctioned, artichokes growing and wine fermenting.

Returning the whole Pacific Rim to more local economies, increasing food abundance throughout the planet and reducing international power politics are all tightly interwoven problems. For instance, the salmon streams of Russia and Japan have all been destroyed or reduced. So Russia and Japan now harvest immature salmon (many born in North American streams). In retaliation, angry North American fishermen have convinced the U.S. Government to extend our fishing property two hundred miles offshore. So global wars start. Salmon and all other migratory species (the gray Whale, the Delta’s beautiful Canvasback duck, the endangered Least Tern) remind us that certain problems require planetary vision.

Cleaning up our own house by restoring streams & rivers and removing dams that block salmon migrations would make our two Hundred Mile Limit appear less war-like. Saving the Bay Area watershed can help foster Planetary Peace.

Direct versus Transferred Economy

A Native economy is a direct economy, an economy that places value on what is already there. Values are complex: oaks are tree-presence as well as bearers of acorns, tule reeds are both singing spirits and basket materials, salmon are annual visitors and smoked winter supplies. They are both personally direct for each person and direct to the place. It is an economy of seasons and migrations rather than accounts. When there are fewer salmon than last year, more acorns are eaten, and the people continue. They continued with the flow of life around the Bay for thousands of years.

Non-natives imposed a transferred economy. Transferred in where foods, materials and cultural ideas that were familiar to the new occupiers before they came. Transferred out were things from the region that had some value elsewhere.

No native way of life could compare with the advantages of a transferred economy in the minds of the colonizers. Things accumulated quickly and buildings were put up simply to hold them. Subsequent waves of regional immigrants have accumulated so much, put up so many buildings, imported so many devices to “succeed” here and transferred so much out that the region has been transformed into an enormous junkyard.

Tourists glide mindlessly through a Barbary Coast romance which has nothing to do with the continuing life of the place—posing for photos in front of boats idled along Fisherman’s Wharf by failing crab catches.

A transferred economy is a multi-bladed, life-mower which eventually jeopardizes the culture that employs it. Empty cans for holding Japanese oysters thrown into the Bay spoil nesting beds for native oysters. Housing tracts cover up topsoil that is essential for feeding people. Miles of pavement the natural flow and seepage of water actually causing floods. Obvious fumes fill the air around us and no one risks thinking we can continue living here this way to the end of this century.

Restoring and maintaining watersheds, topsoil, and native species invite the creation of many jobs to begin un-doing the damage invader society has done.

Recovery of marshlands and tidelands along the Bay (with a moratorium on dumping raw sewage and other pollutants) would invite back the native birds and shellfish which were mainstays of a direct economy.

What are the other ways we can restore the direct balance of life so that it can be shared with native plants and animals? Considering how much has already been changed in the Bay region, how can we become native to what is here now?

Reinhabitory Sketches: First Cuts toward Living in a Watershed Commons

We begin where we are, at our personal moment of perception. We seek a sense of self-in-place first of all, and a community on a human scale, evolving to a community of creatures.

Access steps: Where do I live? What moves me?

Access steps mean transformations—tourism to hospitality; urban renewal to landscape renewal; employment to life work; jobs to calling; recreation to re-creation.

Yerba Buena

Four large blocks south of Market Street, adjacent to downtown, bordered by Third, Market, Fourth & Harrison Streets.

What was it before? The immediate past: hotels and apartments for transients and senior citizens. What else?

And before that? The area must have related to the waterfront. Houses built around the turn of the century are still standing; it is a sunny district and pleasant to live in. Probably between the wars it was claimed by industry and people began retreating to outlying neighborhoods.

And even earlier? Is it true that the Bay once reached up to Mission Street?

Now it is parking lots (covering soil or fill) waiting to become office buildings, motels for tourists and a sport area.

It is a blank canvas, a way of contrasting what absentee landlords and businessmen who live in Mountain View think a city should be and our views on reinhabitation.

As an open space it stands begging for ideas: Should we plant a Redwood forest there? It could be the site of a reinhabitation fair. It could be developed as a neighborhood using the Oklahoma land rush technique: people staking claims and living there in tents while they build their houses.

And other ideas?

San Bruno Mountain

What first struck me about San Bruno Mountain was, why is it still there? Backed into on every side by cities and industries of the North Peninsula, one last holdout of wild Franciscan land.

It felt like a vital open secret, hidden just below visibility in our cultural focus. No Yosemite, no looming Tamalpais. No redwoods. Not even a Bishop pine. It was mercifully the neglected stone, Lapis Exilis. I thought of it as the stone cast away by the builders which, in Jesus parable, it is said we must find and make our corner stone as an altogether different kind of builders. If we could learn to see and involve ourselves carefully with its quiet life, there might be more than hope for the planet and ourselves on it.

Surrounded by the plumbing of S.F’s, railyards, stockyards, cemeteries, dumps, suburban spill-over, San Bruno Mountain is indeed now being recognized as the last 3600 acres of a unique life zone, the last remnant of a truly Franciscan environment left on earth. Developers, at the same time, have also discovered the Mountain and plan a new high-rise city of 20,000 people for its slopes and meadows.

Both the quieter discovery of the richness of its native presence and the concurrent hungrier notice of its cash-value as expendable space makes the Mountain a case in point for meeting of visions taking place in the Bay watershed.

Early in botanical investigations of California, a Franciscan plant zone was postulated to include the entire face of the Bay region, Sonoma to Monterey. A more attentive look in recent years has disclosed a much smaller “Type Area” covering the hills of S.F. and ending at the southern limb of San Bruno Mountain. This inner region, so long overlooked by us was a recognition of biotic range directly lived by S.F. Indians who’s tribal and hunting and gathering territory precisely coincided with the set of conditions that inform the inner Franciscan zone.

As warm valley air rises, cold wet Pacific air is drawn inland through the Golden Gate at the northern end and the Lake Merced gap to the south. The full year-long force of this weather against the arc of S.F. between, has given rise to an apparently treeless landscape where Ice Age plants have been able to survive and other coastal scrub plants have evolved varieties not to be found anywhere else: a dwarf manzanita, no more than ankle high; a buckeye with tough-ribbed, salt weathered leaves. At the same time, in sheltered ravines, the abundance of Pacific moisture releases sub-tropical growth in the very shadow of a grass from Nootka Sound or a flower from Siberia. The scale is vast, wild exposure and intimate texture of abundance.

Village sites of the Awashtes tribelet of the Costanoan Indians remain intact in the lower valleys of mountains surrounded by the plant life used for food, fiber, medicine by their inhabitants. Beside a remnant estuary and salt marsh, once rich in shellfish and waterfowl, the village sites and surrounding plant communities provide glimpses of the ghost of a direct economy. On the other hand, published plans and an Environmental Impact Report for a new super city on the sane sites offer a vision of transference economy at the most advanced stages of inattention to life-in-place. San Bruno Mountain waits right now between these two investments of the earth.

Many of the people who now live around the Mountain recognize the development proposal as a death threat to what little they have left of community and to San Bruno Mountain itself, which is by now a symbol of what we are fast losing to a blue-print vision of place as real estate and community as something to be grid planned and mass produced. This recognition grew in the last five years into an uprising which miraculously has taken the first crucial steps toward stopping the development of the Mountain and demanding that a new look be taken at San Bruno Mountain and its meaning to the Bay Region.

It is pointed out that except for San Bruno Mountain there is no wild land left on the North Peninsula. As such its acquisition & preservation as parkland has made sense to some planners and elected officials. The possibility of a San Bruno Mountain Park is now definitely in the works.

The question that now arises is what kind of park? And it is here that a reinhabitory vision has a chance to move into working presence. Now that more and more people know of San Bruno Mountain, perhaps it is time that the neglected hidden forms of the site become its potency. Already during the battle to save it, the Mountain loomed up as the dominant issue in San Mateo County politics. From neglected stone to lodestone, it has polarized all kinds of anger and longing.

But a different kind of potency has always been the background, potency as native place rather than issue or image. Perhaps we can help that potency to emerge in the formation of a park on the Mountain. Perhaps the concept of Park or Preserve can here be turned inside out, no longer an enclosure under siege, a senescent remnant under glass, but a seed ground, not a place to get away from at all, but a place to get into, not a place to look at, but a place to see from.

Living Here exhibit of Planet Drum's decades-long work in 2018 at the SF Main Library.

Perhaps we can put forward the vision of a new kind of dedicated land, beginning with: what kind of park would any of us make on the Mountain without the Park and Rec. Department? Beyond Nature Interpretive Centers (sic), there do exist many real and untried models. All over the planet are the sacred mountains, groves, & water courses of traditional cultures, Mt. Kailas in Tibet, Prescilly Top in England, Wu Tai Shan in China. These were recognitions of innate potency of Place, and so became places to enter the learning of origin. Australian Aborigines held that particular places were of the Dream Time and a young man might make there his Walkabout as rite of passage, learning his ground. There were routes of pilgrimage, circumambulations, the Center, Omphalos, navel of the world, sacred ways and precincts where use and habit might fall away, learning to be found in earth’s own features. And there were the guides, shaman, hermit, the Old Woman of the Forest, the Old Man of the Mountain who knew their ground, might show you the edible roots, the place where a hawk drinks and bathes in Summer, or precisely the way to get lost. Modern science looks superficial and invasive beside the ancient learning born of generations of attention to a single place.

These might be the blood lines to the vision of a Preserve whose access and exploration are conceived & guided to nurture Preserve and the discovery of an “actual earth of value”. It need be no Olympus or Fujiyama, no Sinai or Gethsemane. The closer and longer we have to look, the more clarity, and a backyard mountain like San Bruno Mountain offers itself easily to the need. The more so since already it bears the wounds of our inattention. Its very lowness on the horizon of our significances becomes the mystery and the learning.