Dora Norton Williams: Friend of Robert Louis Stevenson

Historical Essay

by Nancy Everett, nancynilene@yahoo.com

Originally published as Dora Norton Williams: A New England Yankee in San Francisco Bohemia in the Argonaut, Volume 21 No. 1., Spring 2010

"As I have no children or connection to whom a history of the kind would be of interest, I shall omit all but the brief statement of facts." -- Dora Norton Williams, 1897

Like many stories about lost treasure, this one begins with a map. On April 18, 2006, as my husband and I joined the crowds stumbling through the inky pre-dawn chill towards Lotta’s Fountain, we were handed various earthquake centennial memorabilia—an emergency kit, a flashlight, a key tag, and the day’s newspaper. As the day brightened, I looked over the paper, pausing to study a map of the Great Fire. Grey areas had burned. White areas were saved. There, amid a sea of grey above Telegraph Hill, was a tiny white dot—the very summit of Russian Hill. And just like that, I realized what a fool I had been.

A year earlier, I had gingerly excavated a worn leather-bound suitcase in which my mother had hastily packed my grandmother's family papers after her passing in 1964. Buried amid crumbling stock certificates, wads of utility bills from the 1940s, and my father's boyhood postcard collection was a set of fragile typed onion skin pages, bound with a limp once-pink ribbon. It set down the life accounts of an entire Boston generation belonging to my father's great grandfather, Eugene Norton. His story I already knew well, as it was the crown jewel of our family lore. A rising Boston politician at the age of 32, he had been appointed by Abraham Lincoln to serve as Navy Agent for the Port of Boston during the Civil War. The official appointment signed by Lincoln hung prominently in every hallway of my parents' successive homes. Now I had a chance to get know the rest of the clan.

As I carefully turned the biography's thin translucent pages, I realized the writer had to be one of Eugene's sisters, Dora. In 1897, at age 68, she had written in great detail about the lives of each of her eight siblings—lives led as farmers, salesmen, businessmen, and teachers. Her own account came last—ten pages relating her rural childhood in Maine and her careers first as a teacher and then as daguerreotype tinter in Boston. Then, on the last page, almost as an afterthought, she dropped a bombshell. " I became acquainted with many famous people [in Boston] and that out of it all came the final result of my marriage and my residence in California. As I have no children or connection to whom a history of the kind would be of interest, I shall omit all but the brief statement of facts. We had our home in San Francisco for the most of the 15 years of our life together and went for our vacations to a little mountain ranch which was home for the first two years after our marriage. There my husband died during one of his vacations. Thereafter the place coming not available as a home, I sold it and have since made my home in SF. In 1892, I built a house on Russian Hill which I now occupy. (1897)" As a Californian whose entire extended family lived in Massachusetts or Missouri, I was thrilled to uncover a lost San Francisco relative. But I had no idea where exactly on Russian Hill the house was located. Those who might have known more about Dora had passed or, in the case of my father, were lost to Alzheimer’s. Curiously, my father had never mentioned his San Francisco relation even though he lived in the city after World War II (where he met and married my mother). Anyway, why try to look I told myself—the house had probably burned down in ‘06.

Aunt Dora Becomes the Object of a Great Hunt

The map of the Great Fire contained a clue that changed everything. But where to start? I immediately called my best hope, my mother. Tell me anything you know, I begged. “Your grandmother used to say that a sister of Eugene's ‘stood up’ at the wedding of Robert Louis Stevenson in San Francisco,” she offered. This was stunning. If Dora had omitted that fact, what else wasn't she telling?

I was about to find out. With a single online search for “Russian Hill” and “Robert Louis Stevenson,” out poured a flood of information. Dora's house still stood on the very summit of Russian Hill, one of the few locations to survive the swath of the Great Fire. And it was famous¬—an architectural gem built in the "rustic style” by the post-Victorian architect Willis Polk .

There was even more. The artist who had brought my aunt to San Francisco was Virgil Williams, the first director of the California School of Design (now the San Francisco Art Institute) and a founding member of the Bohemian Club. As for Robert Louis Stevenson, Dora was one of only two witnesses at his wedding (the other being the minister's wife). She was not only his friend, she was the only female confidante of his wife, Fanny. Suddenly, I held the threads of a remarkable life lived among some of the most influential and creative people in the last decades of 19th century San Francisco. As I began my research, I quickly realized that although Dora had a modest talent as a painter, she had a truly outstanding talent for cultivating friendships with people destined for fame. I wondered if I might find bits of her story within the records of these people’s lives. And so I became a novice habitué of the local history libraries and online archival records. I came to respect the marvelous depth of knowledge possessed by their librarians. I plowed through enormous files of correspondence, out of print books, art work stashed in back rooms, and more.

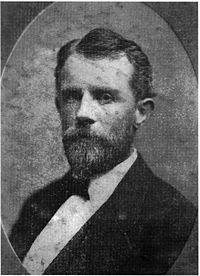

At the San Francisco Public Library I found Ruth Post's book on Virgil Williams, containing Dora's will and the only photograph I found of her. At the Bancroft Library, I found her letter to Ina Coolbrith , written in a trembling hand immediately after the ’06 quake, and other letters to Timothy Reardon and Charles Keeler. At the Stevenson House in Monterey I found a speech written in her own hand describing her friendship with Stevenson. I found Dora's careful ink drawing of Fanny Stevenson hanging in their lobby. At the California Historical Society, I found an original photograph of the Russian Hill house, taken just after it was built. From the Robert Louis Stevenson collection at the Silverado Museum, I was shown a collection of Dora's water colors and the Stevensons’ original marriage license signed by her. The DeYoung Museum librarian took me into the galleries to see a large Virgil Williams painting showing his Dora riding side saddle on a white horse near their cabin on Mount St. Helena. (Although the figure is small and indistinct, I was very touched—this was one of only two images of her I found.) The DeYoung also provided a photograph roughly indicating the cabin location. My husband and I later drove up the side of Mt St. Helena and found the likely cabin site by comparing the actual horizon lines with the horizon depicted in this photo and in a painting of the cabin by Virgil Williams.

But Dora’s friendship with Fanny proved toughest to crack. Citations mentioning letters between Fanny and Dora eventually lead me to Yale’s Bieneke Library. After a few months of insisting that these letters actually existed, I was rewarded by microfiche copies of 21 letters between Fanny and Dora. These, more than anything else, gave me a window into her loyalty as a friend, her insecurities and small snobberies, her sharp tongue, her frustrations as an artist and wife, her loneliness after the death of her husband, and the re-emergence of her bohemian spirit during her Russian Hill years.

Finally, a letter posted to Dora’s house at 1019 Vallejo Street paid off. Amazingly, the house on Russian Hill is still owned by a descendent of Dora's tenant, Julia Caswell, who purchased it after the '06 quake. The current owners, Nielsen and Carol Ann Rogers, kindly invited Richard and I to step inside. We were shown level upon level of ingenious rooms that resembled ship cabins in their tidy use of space. The redwood walls were breathtaking. One of Dora’s water colors still hung on the main floor. As I stood in Dora’s studio in the late afternoon light, it was easy to imagine her at work at her easel or chatting with great animation with one of her many friends.

So, how to pull the threads together? I settled on four phases: her life before San Francisco, her life with Virgil, her friendship with the Stevensons, and her life on Russian Hill.

An Outspoken Yankee Has Her Say

Dora Norton was born in 1829 in Livermore Falls, Maine, one of eight surviving children of an old New England family whose roots went back to the original settlers of Martha’s Vineyard. Her father Jethro made a small living "eked out by various mechanical employments, such as sleigh and cabinet making". Financial difficulties led to a move to Boston when Dora was 14. Her father died of typhoid fever a few years later, but many of the younger Nortons flourished. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Dora's beloved older brother, Eugene, held a key position overseeing vast government expenditures on the retrofitting of war ships based in Boston Harbor. To obtain the appointment, arranged by the notorious anti-slavery senator Charles Sumner, he was given a pass to cross the Baltimore battle lines and travel Washington’s deeply mudded streets to meet Lincoln. At the end of the meeting, Lincoln threw his leg over a chair and declared, "Well, Norton, I guess you will do!" As for the great man himself, Eugene recalled that "Melancholy seemed a settled expression of his countenance."

Dora became a school teacher, joining her sister at a school in Wilmington, South Carolina, just before the Civil War. That this was a difficult experience for an outspoken Yankee there can be no doubt. "I well remember when the attack on Charles Sumner was made by Brooks of So. Carolina there was scarcely concealed satisfaction in the household. Some remarks of my own showing surprise and indignation were, I have been told, remembered, not in my favor, long afterwards."

Dora eventually left teaching and took up a "rather pleasant and lucrative occupation, the coloring and finishing of photographs" at a Tremont Street studio in Boston. She also studied free-hand drawing at Harvard College. She must have made a strong impression on her instructor, Virgil Williams, since she married him on December 6, 1871, when she was 42.

Mr. and Mrs. Virgil Williams Set Sail for San Francisco

When Dora met Virgil, he was an established Boston painter who had returned only a few years earlier from San Francisco. Virgil had met Robert Woodward, a San Francisco entrepreneur and avid art patron, during his art studies in Italy. In 1862, Woodward invited Virgil to assist with the conversion of his San Francisco estate into an art salon and amusement park, Woodward’s Gardens. Over the next two years, Virgil filled the salon with reproductions of the masters as well as his own paintings. He also spent time hunting and painting at Woodward's Oak Knoll Ranch near Yountville. Virgil became enchanted with the area, eventually purchasing a small ranch on the slopes of Mt. St. Helena. (Years later he recommended the area for the Stevenson honeymoon, an experience Stevenson mined in his book The Silverado Squatters.)

Virgil became fast friends with two other landscape painters in town, Thomas Hill and William Keith . The trio spent much time together sketching and visiting many art exhibits hosted by local hotels, such as the Occidental and the What Cheer House. (Virgil resided at the What Cheer, a well known temperance establishment founded by Woodward, and kept a studio at the Mercantile Library Building.)

He also discovered a new passion: the Sierras. Along with Hill he was among the early travelers to the Yosemite Valley, accompanying both the painter Albert Bierstadt in 1963 and the photographer Carlton Watkins in 1865.

In 1867 Virgil, along with Hill, left for Boston. But he still had California on his mind. Encouraged by Hill's own return to San Francisco, Virgil arrived back in San Francisco on August 14, 1871 via the ship Sacramento—with Dora.

The couple did not stay long in San Francisco, choosing to live and paint at the Mt. St. Helena ranch. They were, however, immediately inducted into the newly formed San Francisco Art Association, founded in 1871 by a group of local artists and art patrons. In 1873, Virgil was elected to be the first director of the Association's new art school, the San Francisco School of Design, at 313 Pine Street. Virgil and Dora moved into the city, residing on Taylor Street near Geary. Dora helped run the school and lent a hand as an instructor. The school later moved to 430 Pine Street above a busy fish and meat emporium, the California Market. The school shared quarters with an organization that grew out of the Art Association, the Bohemian Club. (Virgil was a founding member of the club and president from 1875-76.)

Now called the California School of Design, the school attracted many talented students and instructors, including Douglas Tilden, Chris Jorgensen, Grace Hudson, and Alice Chittenden. Dora herself continued to paint watercolors. Her work was listed in several exhibitions over years, including the First Annual Exhibition of Lady Artists of San Francisco in 1885 and the Midwinter Fair in 1894 in Golden Gate Park.

The Charismatic Stevensons Make Their Appearance

Two of Virgil’s first students at the School of Design were Stevenson's future wife, Fanny Vandergrift Osbourne, and her daughter Isobel. In fact, it was Isobel who provided this lively description of Dora:

“…a slim, straight-backed, decisive Yankee woman who prided herself on a frankness that was sometimes rather appalling. She wore heavy silks and velvets, unbecoming hats, fairly rattled with necklaces and bangles, and carried, fastened to her belt, an assortment of silver articles, mesh purse, pencil-case, knife, and button-hook that dangled on the ends of little chains. She and my mother became friends at once.”

This loyal and sometimes testy friendship endured the rest of their lives. As bohemian Fanny later traveled Europe with Stevenson, her somewhat eccentric new friend, Dora, became her only female correspondent and confidant.

After launching an affair with Fanny in France, Stevenson pursued her to Monterrey, and then to San Francisco. It was during Stevenson’s pre-marital tenancy in 1879 at 680 Bush Street that Fanny introduced her ailing fiancé to Dora. Stevenson was gaunt with illness and struck an odd appearance. He paced nervously, smoked constantly, and generally eschewed gentlemen's attire in favor of a well-worn velvet smoking jacket. In Dora’s own words, “I was an invalid about that time and he came to see me with my friend the lady who afterwards became his wife. He was very silent and the call was short. My friend afterwards told me that my look of suffering so roused his pity that he could not talk. He came again the next day for something he had left behind and finding me better, he remained a while and we entered into conversation, and I may add a life-long friendship. It was easy to recognize in him the qualities that have made him beloved far and wide and by those who have known him but slightly or only through his books.”

“While we were earnestly talking and Stevenson had for the moment paused in his walk and was leaning his slight figure on the mantel piece, my husband came in and glanced at him very curiously. I hastened to introduce them to each other. He afterwards told me that he thought some tramp had got into the room and I could not get him out, so peculiar and foreign was the appearance of my visitor. From that hour, however, they became fast friends.”

Stevenson’s famously engaging personality enthralled the Williams. Virgil and Dora saw Stevenson frequently for several months. Dora writes, "...there was an instant charm of manner which seemed to come from earnestness and went straight to the heart." “I recall a certain Sunday trip we all took together to the Park then in the first stages of improvement, and very difficult of access. The way was long, the wind was cold, and my husband and I rather shrank from the prospect. But once started on our way, the gay young enthusiast allowed of not one moment’s dropping of spirits. He quoted poetry, told funny stories and made so many witty sallies that he filled the time with mirth and music and it remained a red-letter day in our memories when he was far away.” Stevenson suffered terribly, however, in the damp and foggy climate. Fanny finally took charge, sequestering him her Oakland home and nursing him back on his feet. Eventually he was well enough to make a fateful trip across the Bay.

Accounts of the Stevenson marriage ceremony vary in the details. But based on separate written accounts by Dora and Fanny , this is what most likely happened. On May 19, 1880, Fanny crossed the Bay alone and met Louis and Dora at the Market Street wharf. The trio walked to the Post Street home of the Reverend Dr. William Scott. With Dora and the minister’s wife as the sole witnesses, Dr. Scott married the pair in his parlor. "When we left the parsonage," Dora recalled many years later, "the Stevensons walked hand in hand, like two happy children who never would grow up." Stevenson later declared that Dora was “my guardian angel, and our Best Man and Bridesmaid rolled into one.” On the recommendation of the Williams, the Stevensons set out to honeymoon in Calistoga. They needed an elevation above the fog layer, however, so they instead spent six weeks in the abandoned, drafty, and half-derelict barracks of an old silver mine. When Stevenson later published The Silverado Squatters about this experience, he dedicated the book: "To Virgil Williams and Dora Norton Williams. These sketches are affectionately dedicated by their friend the author." On the flyleaf of the copy he sent them, he wrote in his own hand a little poem which closes:

"...Back now, my Booklet! on the diving ship, And posting on the rails, to home return— Home, and the friends whose honoring name you bear."

Mrs. Stevenson and Mrs. Williams Exchange Many Letters

Fanny and Dora began a long correspondence filled with gossip, pathos, mutual praise, and sometimes catty remarks. (Stevenson also corresponded, although once in Samoa, the letters mainly contained requests for gift shopping for young relatives.) Occasionally Dora breaks into uncharacteristic detail about her personal life, as in this description of her new home at 826 Green Street (at Taylor):

“We are at present as I may have told you doing some small housekeeping in a little house apparently intended by nature for our use. It commands lovely prospects of ocean and Marin Hills and we see the guns at Alcatraz belch forth at sunset and great China steamers go back and forth and have lovely effects of sky and water continually – for when was nature altogether continually unlovely?”

There are hints that Virgil may have endured a sharp tongue. Dora writes to Fanny, "Yesterday Judge and Mrs. Boalt came and we had a nice luncheon all joining in showing Mr. W. how to cook the omelette, which kindness on our part was, I must admit, met with extreme coldness, and we revenged ourselves by not praising the omelette. But if cooking fails we have perennial photography and after lunch our visit to the sea and taking views of each of the party with dashing waves for background to keep up the excitement."

Here Fanny responds to a complaint about Virgil from Dora:

“Perhaps it would have been better had you never married. But you did marry, and that fact is unalterable! ... I say forget everything else but the fact that you are married and must make the best of it, and get whatever little sweetness may extracted from the bitter.”

And later Dora writes of Virgil’s agonizing death from heart failure in 1886 at their cabin, “I ran for the [hired] man and together we tried to rouse him by raising him up and giving spirits. At last I was convinced that he would never waken more. Being alone with the exception of the man I could do nothing but send him for help a distance of four miles. I remained alone with the dead for several hours. I closed his eyes which were now quite useless forever more and laid the final account of our life together before our Maker and his re-awakened soul.”

And then Dora writes to Fanny, “I have always loved a life far from society but with my own selection of company. How terrible was the solitude my husband had peopled for me when he was gone! Anything but that!”

The Stevensons Return to San Francisco Only to Depart Again

In 1888, the Stevensons returned to San Francisco from Europe (via Saranac, New York) en route to the South Pacific. Dora and other friends surprised the Stevensons by filling their room at the Occidental Hotel with California flowers, although Stevenson was so exhausted from the journey he went straight to bed without comment.

For the voyage Fanny had arranged to lease the yacht Casco from Oakland businessman Sam Merritt. But Merritt, dismayed at the ragtag appearance of Stevenson, threatened to back out. Dora stepped in, saving the day by vouching for Stevenson at her bank. On June 26, the Stevensons set sail for a South Sea's voyage intended to last six months. Dora and other friends saw them off from their anchorage at the sea wall just under Telegraph Hill. They stayed in the South Pacific for six years, eventually settling in Samoa. There was much written in their letters about Dora visiting them in Europe and later in Samoa. But the visit never came to pass. Stevenson died of a stroke in Samoa in 1894.

Everyone Rallies for the Robert Louis Stevenson Monument

Many members of San Francisco Bohemia greatly admired Robert Stevenson. The day news of his death reached the papers, Willis Polk and Bruce Porter met at the Palace Hotel over lunch (and several bottles of wine) to design a monument to Stevenson. Polk drew the plan on the tablecloth, paid the complaining waiter a dollar, and walked off with the cloth tucked under his arm.

Dora raised money for this monument by speaking to local women’s groups. "We hope, here in San Francisco, in a spot he loved to frequent, to raise a suitable memorial to this brave bright spirit; – a memorial where perchance many of the neglected and unfortunate, a class that always had his deepest sympathy, can come and sit an hour, even where he once sat." Fund raising took three years due to objections to the unfashionable Portsmouth Square site, a place Stevenson found fascinating. (Many donors preferred memorial to be placed in the new Golden Gate Park.)

The graceful granite column of the memorial was engraved by Polk himself with Stevenson’s Christmas Sermon. It is topped by a bronze cast of the galleon Hispaniola from Treasure Island. Unveiled on October 17, 1897, it was for many years the site of an annual observance of Stevenson's birthday on November 13. It remains today in Portsmouth Square, bowered by cypress trees, and moved rather forlornly to the side, away from its once central position.

Mrs. Williams Enters Russian Hill Bohemia

After Virgil’s death, Dora raised enough money from the sale of his paintings and the ranch property to purchase land on the summit of Russian Hill. She had several connections to Russian Hill. Her old Green Street house sat at the foot of it. She was acquainted with one of Virgil’s students, Mary Curtis Richardson, who lived there. She may also have been acquainted with the wealthy Livermore family, who hailed from her home town in Maine and who owned property on the hill. Any of them might have introduced her to another Hill resident, Willis Polk, who in turn urged her to purchase property so he could build his first San Francisco house on the summit.

The two reached an agreement and in 1892 Polk built a duplex “rustic house” on the southeastern edge of the summit. Dora lived in the western unit and the Polk family took the eastern. Polk ingeniously designed the building to perch on the steep slope supported by a series of cascading rooms, "suggesting an accumulation of hillside shacks". The top floor was Dora's studio, the next floor was her main parlor, and the lower floors contained the original kitchen and dining room, sleeping porch, and possibly servant quarters. Utterly novel for its day, the interior was paneled in unvarnished redwood, creating a glowing cabin-like ambience. In fact, the house remains a celebrity. A photograph of the newly built Vallejo street house is the cover image of Richard Longstreth's seminal book, On the Edge of the World: Four Architects in San Francisco at the Turn of the Century.

Dora's life on Russian Hill shines a light on the self-pollinating circle of friends that existed in turn-of-the-century San Francisco. Dora was close to Bruce Porter, a landscaper and an eccentric colleague of Polk’s; Oakland resident Charles Keeler, muse of the California Arts and Crafts movement; Gelett Burgess , editor of the literacy magazine The Lark; Russian Hill neighbor Ina Coolbrith, famed poet and Overland Monthly editor; and across the street, Joseph Worchester, who attracted Dora, Polk, Porter, Keeler, Burgess, Mary Curtis Richardson, and many other artists and intellectuals to the “Worchester Group,” his weekly conclave.

In 1895, Fanny and Isobel returned to San Francisco from Samoa and stayed in one of Dora’s lower floors for six months. During this time, Fanny became acquainted with Gelett Burgess, Bruce Porter, and others in the Russian Hill circle.

She and Dora frequented séances in hopes of connecting with their lost husbands. As typical, however, Fanny, played the part of the scold in her note to Dora: “You are very impressionable, nervous, and not fit in the point of view of health. I wished… to see something of the methods of these people, so I went to several of their places in San Francisco, but I took particular pains to keep you in ignorance of the fact. I saw some few things I could not explain, but there were many tricks that could hardly deceive a child…”

In 1899, a now wealthy Fanny hired Polk to design a home for her at Hyde and Lombard. Although their two homes were within walking distance of each other, there's no evidence that the old friends visited each other. Fanny kept company with Gelett Burgess for a time , but eventually took in young man, Ned Fields, to live with her—and by some accounts, to be her lover. The ever-proper Dora may not have approved. The two stayed in touch, however, writing occasionally when either was out of town.

The Quake and Fire Cause Great Disturbance and Upset

Dora's house suffered only minor damage from the earthquake, but the threat from the ensuing Great Fire was very real. A story told on Russian Hill is that the neighbors buried their jewelry and money in the neighborhood park before they fled. The cache is said to have included some of Virgil's paintings but Dora could not find them all upon her return.

According to her letter to Ina Coolbrith, Dora fled the aftermath of the quake to Fruitvale, a suburb of Oakland, with the family of Fanny’s old friend John Lloyd. Her letter to Coolbrith shows shaky handwriting—she complains of an injured hand, but as typical provides no details. She also hears from Fanny, who was at her Gilroy ranch at the time of the quake. Ever practical, Fanny sends a ten dollar bill and some stamps. In the end, the summit of the Hill was saved—whether through luck, location, intent, or a bribe of whiskey is unknown. Dora unhappily returned to a home without gas or water . Photographs show the summit of Russian Hill surrounded by miles of desolation. A year later Dora carried out a long-held wish and moved to Berkeley, residing in a Hillside Avenue house she had bought a few years before. There she died in 1915, outliving Fanny by two years.

Mrs. Williams Teaches One Last Lesson

My journey with Dora showed me something about the past I had not quite grasped. The facts and grand movements of history seem to belong to the famous. But they are in fact witnessed and supported by forgotten characters, who remain anonymous unless with some luck and much persistence they can be persuaded to give up their story. Among Dora's many bequests, she left her collection of signed Stevenson first editions to her niece, Hannah, who became a much loved Aunt Hannah to my grandmother. Unfortunately, I cannot find any mention of these books in the family suitcase—another lost treasure for another day.

General References

____________________________________

Dora Norton Williams, Autobiography. Unpublished, 1897.

Ruth Nicholson Post, Virgil Williams. Calistoga, California: Illuminations Press, 1998.

Margaret Mackay, The Violent Friend: The Story of Mrs. Robert Louis Stevenson. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, 1968.

Fanny Stevenson and Dora Norton Williams, letters. Vault 805, Box 1, Edwin J. Beinecke Collector's Files relating to Robert Louis Stevenson, Beinecke Library, Yale University.

Citations

Williams, Autobiography. All direct quotes of Dora Norton Williams are from this document unless otherwise cited.

Willis Polk (1867-1924) was a versatile and often controversial architect who combined classical styles with vernacular "rustic "elements. His many buildings include the Pacific Union Club, the reconstruction of Mission Dolores, various mansions in San Francisco, the Filoli estate in Woodside, CA, and the Beach Chalet on the Great Highway.

Ina Coolbrith (1841-1928) was an influential writer, poet, and muse of the California literary community beginning in the 1860s. In 1873 she became head of the Oakland Free Library, where she mentored a young Jack London. In 1915 she was named Poet Laureate of California.

Timothy Reardon (1839-1888) was a San Francisco lawyer (and later judge) who was also an editor for the literacy magazine, Overland Monthly. He met Fanny Stevenson through her acquaintance with Virgil Williams. They maintained an intense, often flirtatious, correspondence throughout much of their lives. Although they were never romantically involved, Fanny regarded him as a dear friend.

Charles Keeler (1871–1937) was a naturalist, poet, and artist. Architect Bernard Maybeck persuaded him to become his first private client. From this experience he wrote A Simple Home and founded the Hillside Club in Berkley. Through these vehicles he promoted the ideals of the Arts and Craft movement.

Statement by Charles Harding Norton of his father's recollection of the meeting with Lincoln, Nov. 28, 1920.

Robert Woodward (1824-1879) was a San Francisco entrepreneur who built Woodward's Gardens on his estate between Mission and 14th Streets, alongside his horse car line. Besides a fine art gallery, the four-acre site housed a large zoo, the west coast's first aquarium, and many curiosities including Chang from China, an eight-foot tall giant who paraded the grounds dressed as a mandarin; Admiral Dot, a 25-inch midget; and Monarch, purportedly the last California grizzly, whose capture was funded by William Randolph Hearst and whose stuffed body was eventually put on display at the Academy of Sciences.

Thomas Hill (1829-1908) was a student of the Hudson school of landscape painting who moved to California for health reasons in 1861. During the trip to Yosemite in 1862, he became smitten with the wild and vast scenery. For many years he spent summers prolifically painting in a studio near the Wawona Hotel, Yosemite, where the studio still stands.

William Keith (1838-1911) was among the earliest artists to settle in San Francisco, arriving from Scotland in 1859. He had a long and successful career, producing thousands of highly regarded scenes of the Sierras. He enjoyed a close friendship with fellow Scot John Muir, who called him a "poet-painter". The number of his existing works is small, however, because much of it was destroyed in the San Francisco fire in 1906.

Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) was renowned for his enormous romanticized paintings of the newly accessible American west.

Carlton Watkins (1829-1916) took early photographs of Yosemite Valley that helped persuade Congress to place the Valley under the protection of California as its first state park.

Douglas Tilden (1861-1935) , who became deaf as a child, completed many sculptures located in San Francisco including the fountain at Bush and Market; the Mechanics Monument at Market and Battery; and the Father Junipero Serra and Baseball Player statues in Golden Gate Park.

Chris Jorgensen (1860-1935) followed the footsteps of Thomas Hill and specialized in scenic Yosemite paintings in oil and watercolor. He kept a cabin for almost two decades in Yosemite Valley. He named one of his sons after Virgil Williams.

Grace Hudson (1865-1937) earned a national reputation as a of painter Native Americans, especially the California Pomos. The Hudson Museum in Ukiah houses many of her works.

Alice Chittenden (1859-1944) was known for her floral still life paintings. Chittenden created several hundred oil-on-paper paintings cataloging the wildflowers of California.

First Annual Exhibition of the Lady Artists of San Francisco. San Francisco Art Association, December 1885. " On Tuesday, December 15, 1885, 2,000 San Francisco socialites attended the opening reception of the first exhibition of women's paintings in California. The School of Design proudly hosted this evening in its festively decorated Pine Street rooms. ... From this successful event and others like it, the women artists founded The Sketch Club in 1887". Mae Silver, "1894 Midwinter Fair: Women Artists, an Appreciation", Shaping San Francisco, <www.foundsf.org>.

At the 1894 Midwinter Fair at Golden Gate Park, Dora was among 28 women who showed their work inside the Fine Arts Building. Many of them had been part of the 1885 exhibition. (Silver).

Isobel Field, This Life I've Loved. New York: Longmans, Green & Co.,1937, p.78.

Fanny met Stevenson in Getz France in 1876 during her separation from her first husband, Sam Osbourne . She was 36. He was ten years younger. The two bon vivants started a tumultuous affair that resolved with Stevenson taking an exhausting sea and train journey to reunite with Fanny in Monterey CA, a journey he chronicled in The Amateur Emigrant.

Stevenson's chronic illness was marked by fevers, shortness of breath, and hemorrhaging. It was thought at the time to be tuberculosis or Bright's Disease (nephritis). He ultimately found relief from his symptoms in warm and humid Samoa. But based on the historical information, no modern diagnosis has been determined.

Dora Norton Williams, A Paper Read Before the Century Club of San Francisco in Aid of the Robert Louis Stevenson Memorial, November 13, 1897. Box 16, Subgroup 4, Stevenson House (Monterey State Historic Park), Monterey, California.

"Saw Stevenson Wedded in 1880", San Francisco Examiner, November 12, 1913. Roy Nickerson, Robert Louis Stevenson in California. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1982, p. 85.

Robert Louis Stevenson, letter to W.E. Henley, April 1882. The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, eds. Bradford A. Booth and Ernest Mehew. Yale University Press, 1994.

Bruce Porter and Gelett Burgess, The Lark, number 9, June 1, 1895.

Anne Issler, Happier for His Presence. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1949, p.158.

Bruce Porter (1865-1953) was a San Francisco painter, sculptor, stained-glass designer, writer, muralist, landscape designer and art critic. Among his many commissions are the garden landscapes at the Filoli estate in Woodside, California.

Robert O'Brien, "Riptides, The Sketch on the Tablecloth". San Francisco Chronicle, December 23, 1949.

Richard Longstreth, On the Edge of the World. Berkley, California: University of California Press, 1983, p. 233.

The rustic city house was "a hybrid of (European) picturesque and classical traditions ... first achieved by Polk in a double house on Russian Hill." Both the exterior and interior--as well as the landscaping--sparked a trend away from Victorian gingerbread."Polk's spirited accommodation to the hillside marked a new attitude toward the landscape that would have a far-reaching impact on the area's residential architecture...". (Longstreth, pp. 107-119.)

Gelett Burgess (1855-1951) was chief editor and writer of The Lark, a monthly literary magazine published between 1895-1897. Burgess also founded the San Francisco Boys' Club Association, now the Boys & Girls Clubs of San Francisco.

Joseph Worchester (1836-1913) was a minister and amateur architect who founded the [[The Swedenborgian Garden Church|Swedenborgian Church] on Lyon Street. Both the church and his four cottages on Russian Hill embodied his rustic naturalistic views of buildings and were influential with many leading professional architects.

Williams, letter to Ina Coolbrith, May 1906. Coolbrith Papers, BANC MSS C-H 23, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Williams, letter to Charles Keeler, February 17, 1907. Keeler Papers, BANC MSS C-H 105, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.