Bike Messenger Crackdown 1989

Historical Essay

by Howard Isaac Williams

Originally titled “Our Chance to Speak Truth to Power”

Messenger on Kearny Street, 1998.

Photo: © Kyle Shepard

- “I spoke of Your testimonies/Before kings and I was not ashamed.”

- —Psalm 118 ( or 119) : 46

- “I spoke of Your testimonies/Before kings and I was not ashamed.”

- “Well the one thing we did right/was the day we started to fight.”

- —“Keep Your Eyes on the Prize” Civil Rights Movement arrangement of the Black American Gospel song

- “Well the one thing we did right/was the day we started to fight.”

To respect their privacy, some names have been changed.

The annual SF Bike Messenger Toy Drive that began in December 1984 was just one seed of a cycling culture that would grow into the worldwide bicycling renaissance that saw the births of Critical Mass, the Cycle Messenger World Championships, cycling based physical rehabilitation organizations and other bicycle advocacy groups and events. In the media, messenger culture was increasingly portrayed—sometimes respectfully.

But on the streets, tensions remained with the police. Cops often gave us tickets and in one incident from 1987, officers swooped on a vacant lot where messengers were enjoying an after-work party. Over 50 couriers were cited or arrested for misdemeanors such as open containers of alcohol or possession of marijuana. But as one messenger later succinctly summed it up: “When you grab over 50 people and all you get are 3 knives and no guns … you grabbed the wrong people.”

Nor were messengers the only people to be harassed for trying to make a few dollars on the street. On several occasions I saw motorcycle police riding on the sidewalk in pursuit of little Chinese American kids selling candy. The kids actually seemed to take it in stride, often laughing as they nimbly escaped their armed pursuers. Once, a courier “accidentally” put his bike between the cops and the tykes. After San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen criticized this strange behavior, the police found more important things to do.

Despite these and other incidents, there had been no major crackdown on messengers like the ones in the late 1970s and early 80s.

Then on a September afternoon in 1989, as I rode into the Financial District, I saw my friend Markus Cook. Markus was a musician and courier who was nicknamed “Fur” in acknowledgement of the massive brown Afro perched above his lean face and body. Although he was White, his Afro was a natural one.

“Hey Howard, have you heard about the crackdown?”

“Crackdown?”

“Yeah. Dirt bike cops. They’re all over. I’m surprised you haven’t seen any yet.”

I muttered a profanity.

“Yeah, I feel the same,” he replied before continuing. “There’s a meeting tonight at the Proj Lodge.”

“So we’re gonna do somethin’ about this?”

“Yeah.”

“Cool!”

Located in the Fillmore District, just up the street from San Francisco’s Russian Center, the Proj (rhymes with “dodge”) Lodge was a large apartment that was home to several messengers who hosted marathon parties with live bands, fish fries, benefits for injured friends and other events. That night was the first time it was the scene of a messenger activist meeting. By the time I got there a few minutes late, dozens of messengers had already jammed into the Lodge. I was stuck on the stairs along with a group of other couriers, barely able to move. We could hear the meeting upstairs in the living room but couldn’t get up there. I was frustrated because I wanted to speak. I asked a young woman messenger if I could go upstairs.

“Do you know Matt?”

“No. … But I was in the 1984 crackdown.”

Hearing this, the crowd instantly parted for me and I ascended the stairs.

In the living room, I waited for my turn to speak. Mark “P-Roger” Rowe and Matt “Broiler” Royston hosted the meeting in an informal yet non-chaotic manner … which is not always the case when bike messengers gather.

Up till that time, this was biggest meeting of messengers for an activist cause. Some people called for violence but they seemed to be in the minority.

When I spoke, I seconded those calling for a non-violent response and also recommended taking our tickets to traffic night court.

“That way we won’t lose any work time,” I said. “And we might get Judge Colbert.”

“Who’s Judge Colbert?” someone asked.

Craig Savage, long-time messenger known for grabbing the sides of cable cars to go uphill... the only messenger tolerated by the cable car conductors to do so!

Photo: back cover of Mercury Rising No. 8, August 1993

“A fair judge,” I replied.

Another speaker said there was a rumor that the San Francisco Municipal Transit Agency—the City agency that ran the bus system—had asked the police for the crackdown. In those times, relations between messengers and “Muni” bus operators were often tense and sometimes physical. A few months before the crackdown, after a bus unnecessarily crowded me, I hit the driver’s side view mirror. I only wanted to knock it out of line but unfortunately I broke it, so I sped away. A few blocks later, I noticed my little finger was bleeding. It wasn’t serious but I still have the scar.

And that year the City closed down Market Street for repaving. As a result, outbound traffic crowded onto Mission and Howard Streets, which were already busy streets. This exacerbated our tensions with Muni buses. Hearing that Muni might have called for the crackdown ratcheted up our anger.

After more discussion, we agreed to do a protest ride along Mission Street from downtown to City Hall … while legally occupying a full lane and obeying all traffic laws. By doing so, we would be borrowing a tactic from the labor movement which sometimes follows strict “work to rule” procedures during long negotiations as a way to slow production and frustrate management without actually going on strike.

Finally, the meeting concluded and we all went home to get some sleep.

As the harassment continued, there were still those incidents that have always distinguished our profession. Why should a crackdown prohibit such quirks?

While he was approaching a North Beach intersection, Rafael Richards saw a dirt bike cop, out of the corner of his right eye. Fortunately he hit his brakes just in time to halt at the red light. Unfortunately, it didn’t matter to the cop that “Double R” had obeyed the law and stopped in time. That just made it easier to catch him.

When Double R handed the officer his I.D., he worried that the cop would find out about his unpaid ticket from a few months ago. Sure enough, the cop said that he would have to escort him to the police station to pay the ticket or stay in jail. He was holding a few deliveries but was allowed to radio his office and ask for a relief messenger to pick up his deliveries. His dispatcher sent the veteran messenger Steve “Milo” Mann to the station.

And then in an idiosyncratic example of the longtime San Francisco civic custom of “pay to play,” the police demanded that Milo pay Double R’s outstanding ticket before they would allow him to turn over his deliveries. They knew that Double R’s company didn’t need their messenger now. They did know that the company needed their deliveries now. So the company was willing to pay his fine. And that also meant getting their messenger back on the streets.

For the guitarist and veteran walking messenger Tony “Calzone” Garay, the crackdown offered him a chance to prove the Chinese proverb that there is opportunity in danger.

A few days into the crackdown found the messenger on his rounds for Aero Delivery Service, San Francisco’s largest crew. Aero’s team of walking messengers was larger than the entire walking, bike and motor vehicle rosters of some smaller companies. One afternoon, his dispatcher sent him to the “Wall,” a three foot high structure that snakes along the sidewalk of Sansome Street between Sutter and Bush Streets. Tony was to retrieve an Aero bicycle that had been left there after a bike messenger had been injured and put into an ambulance.

Aero bicycles were distinguished from other messenger bikes by their visibly unique design. Aero manufactured their own messenger bicycle—a low, small wheeled, all steel bike designed to carry loads of over 200 pounds. Messengers referred to the yellow heavyweight bikes as “tanks,” not always affectionately. Although their smaller wheels and heavy weight prevented Aero tanks from being the fastest messenger bikes, a skilled rider could rapidly accelerate or ascend San Francisco’s steep hills.

While a courier on a one speed or mountain bike might occasionally be mistaken for a commuter or recreational cyclist, anyone riding an Aero bike was immediately identified as a messenger.

Tony reached the Wall, retrieved the bike and radioed his dispatcher who ordered him to ride it to Aero’s office, 9 blocks away. He mounted the tank and set off for the company’s base. Knowing about the crackdown, he rode warily down Market Street. At Beale and Market, he checked his left and spotted a motorcycle cop strategically parked across the street … glaring directly at him.

“What’s his problem?” the messenger wondered. “I’m not doing anything wrong.” And at that moment, Tony Garay realized that he was no longer a walking messenger; he was now a bicycle messenger. He continued riding and reached the Aero base without any incident.

Despite the tension of that first assignment, that duty would start over 30 years of Tony Garay’s “gravy dog” bike courier career. ( “Gravy dog” refers to a very dependable bicycle messenger. )

Riding uphill from downtown, Ed Rivas brought his 12 speed Raleigh road bike to the crest of Franklin Street, a 4 lane northbound one way street that parallels Van Ness Avenue. From its high point at California Street, Franklin flattens for a few blocks and then makes a steep drop down to the City’s Marina neighborhood.

Like many San Francisco cyclists, Ed treated the Franklin Street descent as an opportunity to outrace the cars alongside him. Not only does the steep drop enable a rapid pace, there are few pedestrians in the area and a good rider can get ahead of traffic which gives him an advantage for safety. People hitchhiking in rural areas in predawn hours notice that cars travel in herds, seemingly unconsciously. And this happen on city streets, as well.

At the top of Franklin, Ed remembered the advice of his older brother Mike, a longtime messenger. Instead of taking off as soon as the light turned green, he waited while counting to 10 before moving. Mike and their other brother Mario used this tactic to time all the green lights down to the intersection of Lombard Street.

With the waters of the Bay and mountains of Marin in the distance, Ed took off and soon was bearing down on the herd of cars speeding ahead of him.

The 4 lanes of Franklin offer a skilled messenger the chance to use the entire roadway and this was in Ed’s mind as he approached the tail end of the herd. With the wind searing into his face, he saw a straight path and blasted through to get ahead of the herd and close in on the one before him. Perhaps Ed was surpassing the speed of sound because he didn’t hear the siren of the dirt bike cop coming behind him.

But no matter how fast he was going, the cop was going faster. He caught Ed at the bottom of the descent and told him to pull over. He gave Ed a speeding ticket for doing 53 in a 35 mph zone.

It was a Wednesday or Thursday when a group of us assembled in the Financial District to ride to City Hall. I couldn’t make it but I heard a few hours afterward how we did.

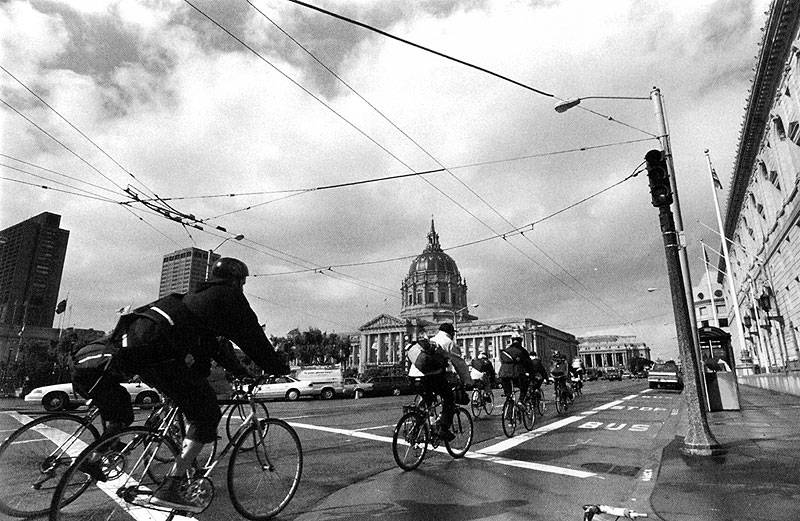

San Francisco’s Beaux Arts style City Hall and its surrounding lawns occupies two full blocks. Under a 4-story high dome, the building commands the view from much of the Civic Center area.

Messengers ride towards City Hall in 1999.

Photo: © Kyle Shepard

Messengers rode slowly down Mission Street, stopping at every red light. At the stoplights, they would pass out flyers to drivers explaining that “Unfortunately because the police are enforcing traffic laws, we are obeying them. Every single one.” Most drivers were bemused instead of angry even as the protesting couriers clogged Mission.

Markus Cook led the chant: “Police harassment really sucks! We just wanna make some bucks!”

Once outside City Hall, someone got the idea to walk back and forth in the crosswalk between Civic Center Plaza and City Hall. Bikes were parked and messengers clogged the crosswalk, forcing cars into a traffic jam back toward the nearby local, state and federal court houses. Someone from Mayor Art Agnos’ office came out and Markus and our other representatives demanded a meeting with City officials. After some discussion, the mayor’s delegate offered a meeting with police and City officials the next day at 3 o’clock.

Just before 3 PM the next afternoon, I showed up at City Hall. There were 4 more of us outside. Kash (“one name, just like Cher”) was there. “Little” Amy Powell was the only woman messenger. Her husband Robert “Teen” Powell was also there but I don’t remember the other courier. Markus couldn’t make it. Someone said that one messenger—Michael Pomusz—was already inside at the meeting. We discussed waiting for other couriers but quickly decided to go inside.

We walked around the metal detector that screened all other people who came into City Hall. That wasn’t a brazen act of defiance on our part. In those days, messengers were allowed to bypass the security procedure installed after the 1978 murders of Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk. According to legend, a bike messenger had personally delivered a document to the mayor minutes before he was assassinated. Whatever the reason, we had long been excused from the security check.

I don’t remember if we took the elevator to the meeting on the 2nd floor. But we probably charged up the stairs because I felt so pumped by the time I walked into the room. My companions must have felt just as energized because they were right behind me. The room was dominated by a table full of officials. Michael Pomusz was the only messenger at the table, along with 2 uniformed police officers and about 6 or 7 other City officials, including two from Muni. Later Michael would tell me that the officials had asked if we were showing up. He nervously said that we were.

But he also said he felt confident the moment he saw us enter and how we looked.

“Howard, I never saw anyone look so mad as you did when you walked into the room.”

The funny thing is I didn’t feel very mad. After 10 years of police crackdowns and harassment, we were finally getting our chance to speak. So that made me more happy than mad. But I guess I must have looked somewhat mad.

We introduced ourselves and for some of us, we were finding out our friends’ real names for the first time.

In addition to the cops, there were officials from Muni, the Mayor’s office and other agencies. They started the meeting by announcing that the crackdown had ended that morning. This sounded right—no one had seen any motorcycle cops that day.

That broke much of the tension in the room. But we still wanted to speak. We made the point that if in the normal course of their duties, the police catch us breaking a traffic law, we expected to get pulled over. But we objected to the police dedicating their time exclusively to pursuing us. If an individual officer saw and cited a messenger running a red light, that was one thing. But for an entire squad to exclusively devote all their taxpayer funded time against us, well, that was unacceptable. After all, we were taxpayers too.

Then we asked who or what motivated the crackdown.

It was the Municipal Transit Agency.

But Transit Workers Union Local 250A—the Muni drivers union—had nothing to do with the crackdown and they sent no representative to the meeting. Ten years later, their union’s avoidance of the crackdown would have positive effects for us. (1)

Then it was my turn to speak. By this time in my life (I was 37), I had seen people overseas fight and die for their freedom. As I thought of those people, I spoke in a manner that I hoped they would have approved.

I repeated our position that a ticket in the process of doing our work was an acceptable risk of our job. But an exclusive and organized crackdown was over the line and not even good for the general public. I mentioned that whenever I received a ticket, I paid it or took it to court. And I added that I had urged my co-workers to also take their tickets to court, a subtle implication that unlike previous crackdowns, we intended to clog up the courts. And then I turned to stare at the 2 representatives from Muni, a middle aged White man in a suit and a middle aged Black woman bus driver.

“And we are unpleasantly surprised that this order has come from Muni whose safety record is somewhat worse than ours.” I exaggerated … but they got my point. Throughout the 80s, Muni had had major safety issues and were in no position to criticize us. Both Muni reps seemed to shrink in their seats and offered no response.

By now, it was almost 4:00. We asked the officials if there was anything else that needed to be discussed. They said there wasn’t which was a relief because late afternoon is the busiest time of day for messengers. It was time to get back to work.

As Kash later said about meeting the City officials, “They seemed surprised that we were functional human beings.”

San Francisco’s decision to halt the crackdown was not only the right thing to do, it would soon prove to be the economically wise thing for the Bay Area economy.

On October 17, less than a thousand hours after the crackdown ended, San Francisco and much of Northern California was sledge hammered by a 6.9 earthquake that killed 63 people and caused 6 billion dollars in damage.

And it closed the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge for 31 days.

For messenger services, this meant that their car and truck drivers could not drive directly from San Francisco to Oakland over the Bay Bridge. Instead of driving less than 10 miles to Oakland, their motor vehicles had to go from the City north over the Golden Gate Bridge, then to San Rafael to cross the Richmond–San Rafael Bridge and turn south to reach Oakland for a total journey of about 30 miles. Not only were the trips longer in distance, they took even more time because those routes were jammed with other vehicles making the same detours.

As a result, courier companies were forced to use bike messengers to maintain communication and commerce between the City and the East Bay. This we did efficiently and consistently throughout the Bay Bridge’s month-long shutdown.

One reason why we adapted so readily was because we had already been taking BART, Caltrain and ferry boats for years. The crisis demanded that we do so on a scale much larger than ever but we met the challenge eagerly and even joyfully, proving that we could do most East Bay deliveries better than cars. As a result, after the Bay Bridge was reopened, some messenger services continued to send us to the East Bay and even to farther parts of the Bay Area.

In the weeks after the crackdown, messengers took their tickets to court. Most, if not all, were thrown out.

In 1989, the Soviet Army retreated from Afghanistan, Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini died, the Chinese Army massacred students in Tiananmen Square, popular protests brought down Communism in six Eastern European nations and the Berlin Wall crumbled.

And in 1989 San Francisco bike messengers defied their City’s government and then helped their City’s economy recover from a major earthquake.

(1) In 1999, Claire Caldwell, the Secretary Treasurer of TWU 250-A, reached out to the San Francisco Bicycle Messenger Association and invited us to meet TWU representatives in order to decrease the tensions between our two groups and improve safety. The meetings were successful and messengers noticed an improvement on the streets.

Dedicated to the memories of Markus Cook, Steve Mann, Amy & Robert Powell, Mario and Mike Rivas.

Thanks to Airplane, Rick Bline, Rick Byrd, Tony Garay, Kash, Carla Laser, Ed Rivas, Mark Rowe, Mike Russo and Jim Swanson.