Bike Messenger Crackdown 1984

Historical Essay

by Howard Isaac Williams

Originally titled “When the Going Gets Tough ...The Tough Drive Toys”

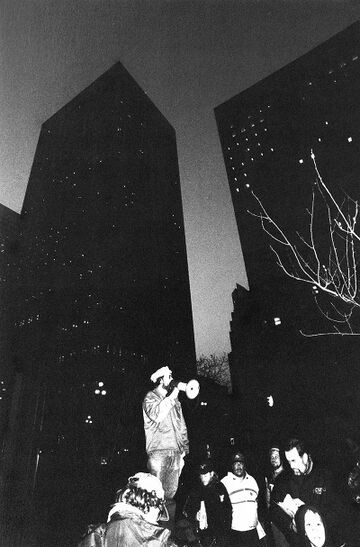

Howard Williams speaking at the Wall, 1999.

Photo: © Kyle Shepard

On a wintry day in late November 1984, less than a thousand hours after the re-election of President Ronald Reagan, a San Francisco public bus opened its exit doors and a few passengers stepped off. One of them was a little girl ... or an elderly lady. Accounts vary but all agree that she was then struck by a bicycle messenger. Next, the messenger rode away, either because the little guy had been physically threatened by wannabee "heroes" ... or because he would have anyway.

Whatever his motive, he got away.

Fortunately the victim, young or old, had not been badly hurt.

So began the Dirt Bike Police Crackdown of 1984. This persecution of bicycle messengers often seemed to take more from Max Sennett’s Keystone Kops than George Orwell’s secret policemen but the author of 1984 would have recognized much in the attitude of a City concentrating police efforts against working people.

And for the rest of that year, police officers riding Honda off road motorcycles harassed San Francisco's bicycle messengers. The "dirt bike" squad was chosen for this operation because police cars weren't nimble enough to catch bicycle couriers on Financial District streets, the most crowded in the City. In San Francisco, messengers had always been ticketed for running red lights and the occasional illegal left turn as well as other infractions. And for being perceived as committing an infraction. But such matters had always been a part of the police officer’s duties and part of the messenger’s risks. In 1984’s last month, when, as in most Decembers, property crimes, drunken driving and other serious matters tend to increase, squads of motorcycle police officers were pulled from all over the City to concentrate on chasing men and women riding bicycles.

While writing up tickets, cops checked each messenger for "priors"—unpaid tickets, outstanding arrest warrants or failures to appear in court—any of which could result in an arrest and at least a night in jail at the Hall of Justice, routinely called the Hall of Injustice.

When the cops did find a messenger with priors, they radioed for a paddy wagon. And just after receiving his ticket, the messenger radioed his company for another courier to pick up the packages he was holding. In the few minutes before temporarily losing his freedom, the courier would get on the walkie-talkie to alert his dispatcher who then ordered another rider to go to the soon to be incarcerated rider and retrieve the deliveries, hopefully before the paddy wagon arrived.

On one such occasion, when the messenger arrived to pick up the deliveries from his arrested co-worker, he rode from the busy street onto the sidewalk for less than ten feet.

And was promptly cited for riding on the sidewalk. Fortunately he had no priors and was able to receive the packages from his arrested colleague.

On another occasion, the paddy wagon arrived before the relief messenger. Seeing that his innocent deliveries might be incarcerated as well, the jail-bound courier flagged down a messenger from a different company who agreed to take the packages and hold them for the company's relief rider.

Yet on most of these occasions, the messengers were accommodated by the police. It wasn't because our employers had any pull Downtown. They didn't. And it wasn't because our clients had any pull Downtown; they didn't need any pull with Downtown. Our clients were Downtown. Then even more than now, we delivered the paper that was the lifeblood of the financial capital of the western USA. Bank checks and statements, stock certificates, cash from the Federal Reserve Bank's regional branch, court filings and other legal documents, news articles, wire service reports, ad copies, lab work and medical bills, cases of wine and other gifts, architectural blueprints, photographs, flowers and everything else "from paychecks to pacemakers" were delivered by over 300 bicyclists usually within an hour … or in minutes for rush jobs. And our cargos also included a few "hard copies" of the codes and algorithms that would eventually yet severely shrink the demand for our profession.

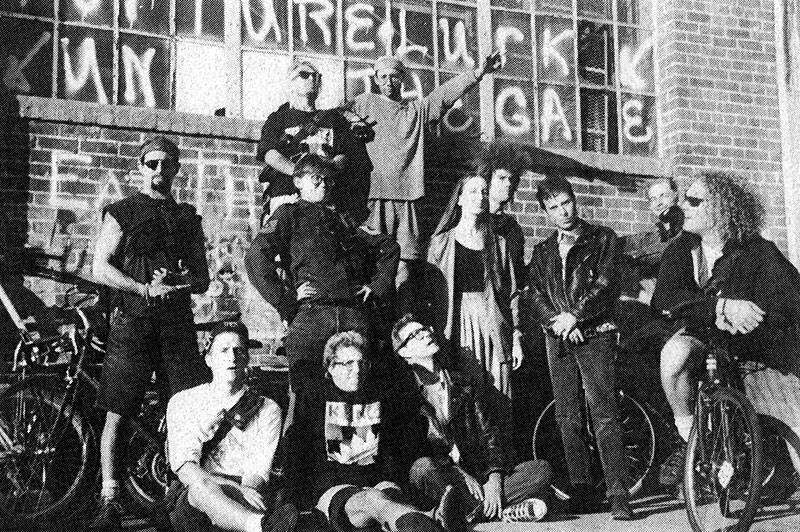

San Francisco messengers in Berlin, summer 1993.

Photo: courtesy Mercury Rising.

Although I had been ticketed on the last week of November, I didn't associate that with any crackdown. My ticket seemed to be an example of a cop doing his job. Whenever a cyclist approached a red light intent on running it, his last concern was getting pulled over by a cop. The messenger's only consideration was to bust a move that would not collide with any person or vehicle. Being distracted by looking for police for only an instant could mean harming self or others in a brutal accident.

It was on the morning of Monday, December 3 when the full force of the dirt bike squad was unleashed on the Financial District. At least 20 officers, usually in pairs, appeared on downtown streets and swept out from behind parked trucks, dumpsters or other hiding places to pull over messengers. And so pay less attention to other matters normally required of police officers.

Despite my ticket of the previous week, I knew nor suspected any of this that Monday morning when I ran into Kimberly "Katastrophe" Hood and Roberto Dominguez a few blocks away from the Financial District.

"Have you heard?" she asked me.

"No, what?"

"You don't know?" Roberto added.

"Know what?!" I replied with some irritation.

"There's a crackdown," Kimberly began. "All the cops on Honda dirt bikes are going after us. This looks worse than '81."

She looked worried. Kimberly was a well tattooed, black clad veteran messenger who had faced the extra risks and dangers sadly familiar to women couriers. If she looked worried … I was worried.

Roberto and I had started messengering in 1982 so we had missed the previous crackdown that Kimberly had mentioned. We were an All American trio; Kimberly was the granddaughter of Armenian Holocaust survivors, Roberto the long brown haired son of El Salvadoran immigrants and I'm a White “Heinz 57” with ancestors from Ireland to Serbia.

"What are we going to do?" Roberto asked.

I mentioned that we could take our tickets to night court and try to get on Judge Colbert's docket.

"A soft spoken Black man with a medium Afro?" Kimberly asked.

"Yeah, that's him."

"Yeah he's good,” she added.

"That's if we get a ticket," Roberto said. "Isn't there a way to not get tickets in the first place?"

Kimberly shrugged her shoulders. “Good question. … Be careful, I guess."

There are a few reasons why "Obey all traffic laws" wasn't and isn't the answer.

Traffic laws are made for motor vehicles weighing at least a ton and able to jump start to speeds of a mile a minute. On at least three occasions in my life, stopping at a red light would have gotten me obliterated by a car. In one case, by two cars. On other occasions, jumping a red light gets me ahead of and away from traffic, which should be the proper order of things.

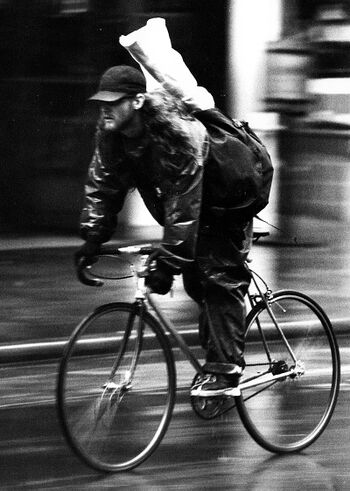

Messenger rushes down Kearny Street, 1998.

Photo: © Kyle Shepard

Another reason is that in those times, most San Francisco bike messengers were paid by the delivery, not by the hour. The more we delivered, the more we made. And if a courier didn't make enough deliveries to cover the $3.35 an hour minimum wage, he or she faced dismissal. Like many messengers, I averaged around $8 an hour. That was about the same as the national blue collar average but just enough to get by in an already expensive San Francisco. So running red lights meant making enough to live on in the City.

The next day December 4 late in the afternoon, I was westbound on Geary Street toward Union Square, the upscale shopping district just west of the Financial District. I was riding on the right side of the one way street when I heard a siren. I turned and saw two cops on dirt bikes. I slowed to let them pass but one of them told me to pull over. After I dismounted, he told me that I was getting a ticket for riding in the Bus & Taxi Only lane. I pointed out that the vehicle code required me to ride as far to the right "as practicable." He said that didn't apply. That made me nervous. As Billie Holiday stated, when you’re not doing something wrong, the cops can be even worse than when you are. But he only wrote me up a ticket.

So obeying the law didn’t even help.

In those days, if a pedestrian paid a little extra attention to activity on the street, they would notice cyclists wearing walkie-talkie radios holstered either on their belts or in a pouch on a "Darth Vader bra," a black cloth fabrication that was secured around the wearer's torso enabling the person to use the radio without stopping his bike. On the front of the rider's inelegant yet sturdy one speed bicycle; the "ped" would likely spot a basket full of packages, envelopes and other items secured by bungee cords. Above the rear wheel might be a rack also bound by bungees. A good rack served as a valuable tool. When a messenger would be challenged to carry over 100 pounds of cargo, she could secure a big part of that on the rear rack to balance the packages up front in the basket and keep the bike from tipping over. A license plate was secured on the back of the seat or attached to the rack. As the result of an earlier crackdown, the City government had passed a law requiring messengers to visibly display a license plate with a number and their company name. The number was so that the messenger could be identified if he fled from an accident. But the messenger was often identifiable, anyway. He or she might be well tattooed and pierced, their denim or leather vests and jackets distinguished by various patches or colorful painting. And if the messenger looked nondescript in jeans, T shirt and a jacket, then he was describable for being nondescript, at least by messenger standards.

Also in those days, if a bicyclist was riding on downtown San Francisco streets between 9 AM and 4 PM, that rider was almost always a messenger. There were no bike racks on the sidewalks and no bike lanes on the streets and no advocacy group to represent the tiny fraction of a percentage of San Franciscans who rode on a regular basis. Even the San Francisco Bike Messenger Association (SFBMA) was still in the future. Except for a few bike riders brave and/or insane enough to commute, about 300 messengers were the only cyclists riding on downtown streets in a City of over 700,000 people. In the 1980s, whether we wanted to be or not, San Francisco bicycle messengers were rugged individualists.

A few months before, two dirt bike cops had ticketed me for an infraction. I had overdue tickets so they escorted me to the Hall of Justice to pay up or go to jail. Fortunately I had just cashed my paycheck. All but about $20 went to paying tickets that would keep me out of jail. While I waited to pay my tickets, the two cops who had escorted me there went into a nearby room and then had a "private" conversation loud enough for me to hear.

"I hate bike messengers."

"So do I. We ought to take a couple weeks just to f- - k 'em up."

At the time I chalked up their conversation as exaggeration.

This was no exaggeration. And they were doing it in December, of all months.

December is typically the toughest month for messengers. Each morning, in the early hours after its rise, the Sun would lie low in the southeastern sky and like a knife of light, its rays would slice straight into the eyes of messengers riding toward their company base offices. In the afternoon, the Sun would lie low in the southwestern sky and again unsheath that knife of light straight into the eyes of messengers riding toward the local, state and federal courthouses of Civic Center. Riding on dark, rainy days, bikers had to avoid human waves of holiday shoppers while dodging drunken drivers leaving office parties. At 5:00 PM, after the Sun had set and the long Winter night was beginning, many couriers were still on the clock.

And now this December was already tougher than previous ones.

On December 7, the Japanese made motorcycles swept down on us even harder.

I was riding on Front Street north of Market toward the stoplight at Pine, now turning yellow. I rode through just as it turned red; from the corner of my eye, I saw a dirt bike and then heard a siren.

It was the same cop who had pulled me over on Tuesday.

After he wrote me up for running a red light, I said "I'm gonna beat that ticket you gave me on Tuesday ... and this one."

"I hope you do," he replied sounding neither sincere nor insincere. Then he added, "If I pull you over again, I'll take you to jail for defying a police officer."

That sounded sincere.

He drove away while I stuffed the ticket into my jacket pocket.

"We can't take this laying down," I muttered to myself.

One wintry morning, some messengers were laying down on the floor of the flat above Maz's Cafe in the South of Market neighborhood.

Maz's was a funky cafe in the South of Market neighborhood that catered to construction workers, auto mechanics, printers, couriers and other blue collar workers along with a few homeless persons. Maz was a short, portly, balding Arab American man who could be cheerful or no-nonsense, depending on the situation.

The flat above Maz's was nicknamed The Maz and was the home of Lee Mallory, the singer, songwriter and guitarist who had cult followings in Seattle and Amsterdam but not enough places in between to gain the rock star riches his works deserved. So he worked as a bike messenger to make enough between tours and other gigs. Lee was highly esteemed in the messenger community and had become the first President of the Hanx. You may have heard people describe their social group as a "drinking club with a bowling problem" or a "drinking club with a crocheting problem." The Hanx are a "drinking club ... with a drinking problem."

A Hanx is sometimes defined as a San Francisco bike messenger who is not a member of the Jak’s. But a Jak can still choose to be a Hanx. The Jak>s is the legendary skateboarding club whose founders include messengers. Basically if a San Francisco bike messenger is not a Jak, he or she is automatically considered to be a Hanx, whether they like it or not.

And so this chilly morning found a group of Hanx lying down on the floor of the Maz (the flat, not the cafe).

They were not lying down because they were too hung over to rise. Yes, they were hung over but that was not the reason for their immobility. These Hanx were lying down because they had drunk so much that the heavy quantity of carbon dioxide they had exhaled all night had been infused with the vapors of so much beer to create an air pressure so dense that it had flattened these men to the floor. Fortunately they were familiar with such a situation and would in a very few hours, as they had on past occasions, rise, open a window and inhale just enough chilly air to reactivate just enough brain cells to function. But before the rest of them would do so, one of them would rouse himself from his position of horizontal extremism to sit up straight. This Hanx was known as Count Gramalkin, a lean courier with sharp facial features framed by straight blond hair that flowed onto his shoulders. He had long enchantingly admitted to being refined, charming, dignified, articulate, psychic, handsome, suave, talented and certainly modest.

Gramalkin then managed to push his right fist through the thickness of the musty atmosphere and even extend his index finger heavenward to proclaim: ”Let's give something back to the City and have a bike messenger toy drive!"

From this moment was born the Hanx Toy Drive and what is now known as the Hanx-Jak>s-SFBMA Toy Drive, an enduring San Francisco Christmas tradition, associated with the SF Fire Department’s toy drive, the nation’s oldest.

From this moment the Count would come to be knighted by President Mallory as the Hanx Commissioner of Toys, a responsibility he exercised honorably for over 35 years until he was finally felled by cancer in 2020.

From this moment, the Count decreed that the date of the toy drive would be the second Saturday of December and that in the event of heavy rain or any other inclement weather, the date would be ... the second Saturday of December.

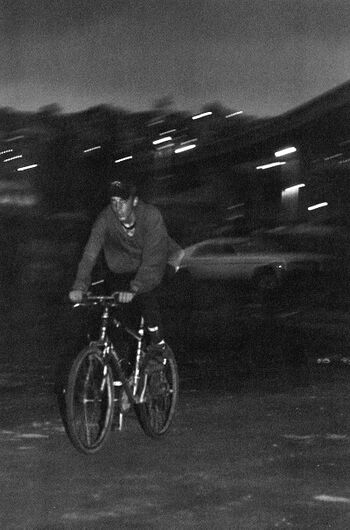

Messenger working at dusk on Berry Street, 1999.

Photo: © Kyle Shepard

And so on Saturday, December 8, these Hanx and some friends gathered under the barren branches of the sycamore trees of South Park, a tiny enclave of green in the South of Market neighborhood, barely half a block north of the Maz. Each person brought at least one toy and huddled in the cold, drinking beers, sharing food and conversing throughout the afternoon. J-Bone Abernethey, a soft spoken yet highly respected Hanx was there and in honor of the occasion, he wore his blue denim vest bolstered by dozens of safety pins, each representing a prayer by him for the South African children then suffering through apartheid. Defying the cold, the Denver native's chocolate brown head was shaved except for his prominent Afro-Mohawk.

Late in the afternoon, the Fire Department's 1950 red salvage truck drove up and collected the toys. And so the messengers gave something to the City.

This event has been repeated on every second Saturday of December since, regardless of weather.

On Sunday the 9th, after Church I went home and studied my calendar. In the first week of December, I had already garnered two tickets. At the rate of two tickets a week, even if I went to court and got them reduced to about $30 each, I’d lose a week’s pay in the month. Making rent would be a problem. Christmas would mean buying cards, not presents. And if I got only one more ticket, I had to hope that it wouldn’t be from the cop who threatened to throw me in jail.

But the calendar also pointed toward a chance. As tough as December can be for messengers, the darkest month does offer some hope. Although there were still three weeks left in the month, the last full week would be a slow one. Tuesday was the 25th and we’d be off; no need to worry about tickets on that day. And being a Monday before a holiday, the 24th was guaranteed to be a slow day. Same for Monday the 31st. And the week between Christmas and New Year’s was always the slowest in the messenger business. From the 24th till the 31st, we would spend more time standing by waiting for orders than riding our bikes. So if we could reach Friday, December 21st without too many tickets, the odds would turn in our favor and we might continue to barely afford to live in San Francisco.

On Monday the 10th, work resumed and so did the crackdown. A couple days with heavy rain forced the cops off their dirt bikes and into squad cars. Once, I saw my nemesis who had threatened me sitting in the passenger’s seat of a squad car; I just smiled arrogantly at him. On a rainy day, I was tough enough to handle the weather while he sheltered in a car. I smiled … but then I busted a quick yet legal move out of his vicinity.

And by now we had adopted some evasive tactics. One of the more unsafe ones was literally watching our backs too much, looking for cops behind us instead of watching our front or sides. And to avoid getting tickets for being in bus/taxi lanes, we often found ourselves among the cars in the left lanes. Some of us rode on the sidewalks because this illegal ploy made us less visible to the cops looking for us on the street. I tried to obey more traffic laws but didn't feel any safer for myself or the pedestrians. And like other messengers, I was on the radio begging my dispatcher Ted Sugioka to get me out of downtown.

“ ‘Uncle’ Ted, get me some tags outta downtown."

"No way Howie, I need you downtown."

"If this keeps up, I won't be downtown. I'll be in jail!"

"Don't get caught," he replied in a laconic tone.

For J.X. Jones the mid-December day had been good but it was still not finished. The reliable rider had logged in over 20 deliveries at U.S. Messenger, one of the City’s Big Three courier services. His output had been good but not nearly as much as he had done on his better days. With the crackdown on, he had been overly attentive about the police and his vigilance had paid off … so far. On a December evening, Jones pedaled his cycle out from the “bike room” at U.S. Messenger, in the alley behind Maz’s Cafe and rode into the night. He expertly navigated the South of Market streets up to Market Street itself and crossed it into the Tenderloin, then as now, one of San Francisco’s most dangerous neighborhoods for both traffic and criminal activity.

He rode west toward Turk Street Studios where his band Greed, Inc. was practicing that night. In addition to his regular duties as the group’s alto saxophonist, on this night he had the added responsibility of scoring beer for the band. Like many working folk, he believed that the best tasting beer was the first one after a hard day’s work so he planned to get a low priced brand. For $3 he could cop a 12 pack at the little neighborhood market close to the studio.

The store was in sight with only an intersection between it and him. The traffic light was red but even in the dark, he saw that it was safe to cross. And then, all in the same second, he blew the light, heard a siren and was being pulled over.

The dirt bike cop had come out of nowhere to give Jones his only ticket of the crackdown.

After band practice, J.X. Jones held a burning cigarette to the ticket and reduced it to ashes.

For Marcel Rosales, mid-December meant the 14 year old youth was off for two weeks from high school, giving him his second chance to work as a bike messenger. His first chance came a few months before during that summer when he asked his father Orlando Rosales for a job at Aero Delivery. His Dad was the senior dispatcher at Aero, home of the City’s largest messenger fleet and Marcel was growing up often hearing how his Dad was considered best dispatcher in San Francisco.

But Orlando Rosales told his son that if he really wanted to work for him, first he would have to work at Speedway Delivery for Charlie Lutge, Orlando’s protege and also a highly regarded dispatcher. Being a dispatcher is similar in principle to being an air traffic controller and although the stakes are not as high, the job can be almost as stressful. Just as an air controller must coordinate the flights of different airplanes to depart and arrive safely, a dispatcher must coordinate the routes of walking messengers, bike couriers and delivery drivers to provide safe and timely service.

“You go work for Charlie Lutge,” Rosales told his son. “He’ll teach you how to be a bike messenger. Then you come work for me.”

But when Orlando heard about the crackdown he told his son to be careful and take no unnecessary risks. The father’s advice proved helpful and Marcel went on to endure the crackdown without a ticket. Even at the age of 14, the youth was tuned into the rhythms and realities he had seen on the streets of the Mission District, the city’s oldest neighborhood. And even at that age, he saw the absurdity of having squads of his hometown’s police force swooping down on a few cyclists while drunken drivers, shoplifters and career criminals were using the holiday season as cover.

In the hours before December 25, the crackdown began to crack up and die. The reason may have been secular rather than spiritual or celebratory, having more to do with the tapering off of legal and bank business than with any surge of good will toward all.

With December 24 falling on a Monday, messengers had so little work that day, we spent most of our time idling on “stand by” instead of delivering. Delivering less meant riding less and not offering easy pickings for our uniformed pursuers. As in all years, the last full week of the year was also slack, giving messengers little to do and finally compelling the police to go back to finding real criminals.

In those times, on the last business day of each year, it was the custom for San Francisco’s office workers to make a winter wonderland in a City that never saw snow. Secretaries and CEOs, mail clerks and accountants opened their windows and began throwing out the leaves from their desk calendars along with yards of ticker tape and other paper that would be useless in the coming year. Monday, December 31, 1984 was no exception. Sheaths of papers floated out of windows high above the streets to form an imitation blizzard. Financial District streets were blanketed by white paper and in some places, the stationery was so thick that it was a challenge to keep traction while riding a bike through it. Pedestrians had to be careful too. A smooth sole could easily slip on the rough draft of a financial report. And as on most December 31s, we took off early partly to ensure that we would survive another year on the streets.

In the first week of 1985, I got a ticket, my fourth in six weeks. The next month, I challenged them in night court. There the very Honorable Judge George Colbert ran his fingers through his Afro and dismissed the two December tickets I had vowed to beat and then sliced the fines for the other two. As someone who regularly walked to work from his home in the Fillmore, perhaps he appreciated the fact that bike riders are safer than car drivers.

For many, many months afterward, whenever I heard a motorcycle behind me, I would immediately jolt. This Pavlovian reaction lasted so long, I thought it would always be with me.

The 1980s would see more crackdowns but none as intense as the one in 1984 ... until 1989.

But in 1989, everything changed.

On Saturday, December 12, 2020, and Saturday December 11, 2021, despite the COVID-19 Pandemic, messengers showed up at San Francisco’s South Park to safely participate in the Toy Drive. On Saturday December 10, 2022, despite heavy rain, messengers again ran their Toy Drive, the 39th Annual.

Dedicated to the memories of Claude "J-Bone" Abernethy and Count Gramalkin who both rode away from this world in 2020 and also to Kimberly Hood, Lee Mallory, Orlando Rosales and Ted Sugioka who departed in earlier years. Note: Some names have been changed to respect the privacy of the persons described.