Before Local 2: Waiters Union Local 30

"I was there..."

by Kevin Mahoney

When I came to the city in the 1970s from Minnesota, I was a banquet waiter or an "extra" working out of Local 30 (Waiters and Dairy Lunch Men).

Fairmont Hotel Gold Room hosting the Archaeological Institute of America, 2010.

Photo: courtesy AIA News

Each of the major hotels were limited to a certain number in in-house banquet waiters and they were limited in how many people they could serve. If you had a banquet that needed above and beyond, that required "extras" from the Union Hall. Each team of two could only serve 3 tables of 10 for dinner and four tables of 10 for lunch. We were a unique bunch of workers because we worked at a different hotel every day. Some days there was work, some days there was not. We were there for any event of any size at all in the City. We would come to work one night and it might be a party for the President of the U.S. and the next night at a different hotel it could be a retirement party for an elevator operator. (I've done both back-to-back).

As a waiter we became flies on the wall amongst the city, state, and national movers and shakers. You are invisible and it gave us a unique perspective. It's fascinating to interact with "important" people when they didn't think anyone was looking. You learn a lot about politicians, executives and leaders when they forget that you are standing over their shoulder putting dressing on their salads.

Every day work slips were doled out for the different hotels. It was a very lucrative situation. I was able to put myself through school just working 12-16 hours/week, not to mention I got full benefits.

At that time, waitresses were not allowed to have those banquet jobs and could not work banquets in any of the hotels. They were relegated to the Sheraton Palace which was a dump. They had Coke machines in the lobby and not enough dishes to serve an entire ballroom. For the most part waitresses were elderly.

When Local 30 was forced by the national union to sell our building we eventually had to merge with the Waitress Union. It was a very unpopular decision at the time, mostly because it added more people, diluting the pool of employees. But it was inevitable that women would eventually be allowed to work in the catering departments of the big hotels in San Francisco.

Banquet waiters/waitresses always worked in teams, so you always had a partner. When the first and only woman to ever work outside the Sheraton got a work slip, given to her by a female dispatcher (she was one of two dispatchers). I was lucky enough to get picked to be her partner. The union wanted it to be a success and I guess they thought that I would not only be kind but help her succeed.

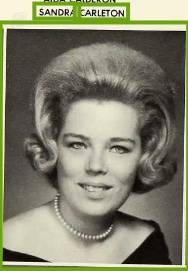

Her name was Sandy Carleton and her first job was a dinner at the St. Francis Hotel. When she showed up, stunned silence does not describe it. All eyes were upon her.

Local 2 restaurant workers demonstrate outside the St. Francis Hotel, July 21, 2015.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

After the others saw that she was not only nice but could do the work she became an accepted member of the workforce. The integration of other women did not follow right away, but soon waitresses from the Palace were allowed to start to work with the rest of us. By then Sandy had earned the respect of all the waiters and the managers at all the hotels and was firmly "one of us." She was held in high esteem by all the waiters. To call her brave was a gross understatement. Not because she was the first, but to throw a young naïve woman into that group of people and situation would be enough to curdle anyone's blood much less to survive and earn her way.

Sandy is now deceased. She should be remembered as a leader in San Francisco as someone who broke barriers for women. She was an unassuming, kind single mom from Daly City who had no intention of rocking any boats. She was thrust into our small spotlight. She was just a hardworking 25-year-old woman trying to make a life for herself and become a waitress.