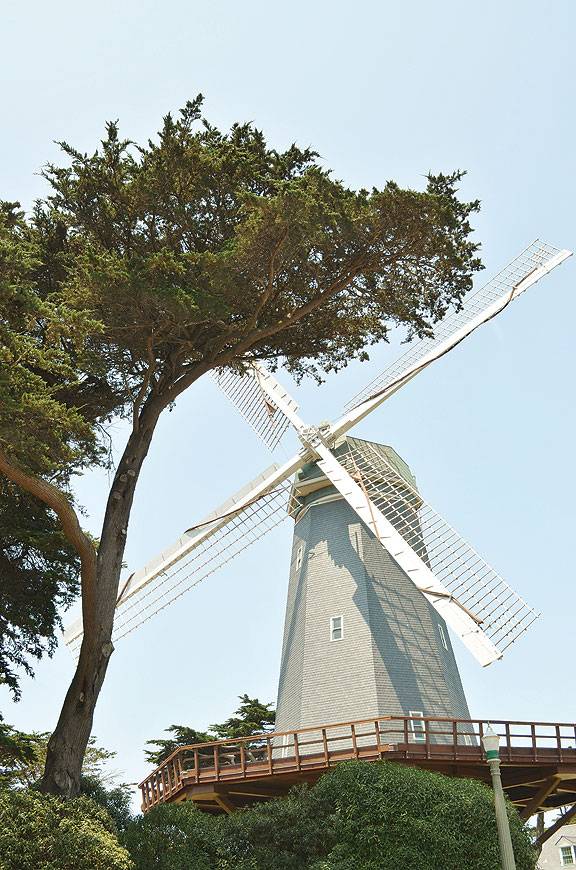

Murphy Windmill

Historical Essay

by Art Peterson

The Murphy Windmill—named after Samuel Murphy, the windmill-loving philanthropist who donated $20,000 in 1908 to pay for its construction—is said to be the largest structure of its kind in the world. The Murphy, located at the southwest edge of Golden Gate Park, joined the 1902 Dutch Windmill, a quarter-mile to the north, in performing the vital duty of drawing water from underground springs to green the western end of the park.

Murphy Windmill at southwest end of Golden Gate Park

Photo: Art Peterson

This once desolate area needed all the help it could get. In 1867, Mayor Frank McCoppin, recognizing that a growing San Francisco population would need open space for recreation, proposed a park on what was known as the Outside Lands. As this part of town was a howling desert of shifting winds, no real estate interests were competing for the property, so the idea went forward unimpeded.

The challenge was to turn dunes into a park. The city approached Frederick Law Olmsted, the dean of American landscape architects, who, in 1858, had completed New York’s Central Park. Olmsted said, “Sorry,” thinking it couldn’t be done, even wondering if “trees that delight” could be grown in San Francisco.

This negativity did not infect William Hammond Hall, a 25-year-old engineer, hired in 1870 to produce a topographical map of the 1,013 acres that were to become Golden Gate Park. Full of ambition, but with absolutely no knowledge of landscape architecture beyond what he had read in books, he signed on to make a park. Perhaps surprisingly, the area to the east of what is now 14th Avenue proved not much of a problem. Hall discovered dark sandy loam with excellent drainage and underground streams that provided plenty of water. The difficulty was to be with the remaining 730 windswept, treeless and sandy acres sprawling toward Ocean Beach. The plants, which he hoped would take hold, could not survive long enough to put down roots. Then one day, barley from a horse’s feeding bag fell in the area. The barley took hold, and when Hall mixed it with lupine and manure he had his recipe to bring bloom to San Francisco’s desert. By 1879, Hall had planted 155,000 trees in the park.

But the trees needed water. The monopolistic Spring Valley Water Company was happy to meet the demand at exorbitant rates. When John McLaren, the legendary and long-time park director, took over park duties in 1887, he was shocked by the water bill. He pushed a plan for windmills at Ocean Beach, which would draw on underground springs near the ocean’s edge. That’s when Murphy came to the rescue. The windmills churned away just beautifully, pumping as much as 1.5 million gallons a day. In 1913 electric pumps were installed, making the rotating sails irrelevant. As the structures no longer served a practical purpose, they encountered years of neglect. By the 1990s, either the windmills had to be repaired or they had to go. Thus alerted, during the next decade the city and private donors contributed significant money for restoration of these landmarks. They are now looking about as good as they did a century ago, and not a moment too soon. These days, wind power is back.

Excerpted with permission from Art Peterson's book, "Why Is That Bridge Orange?" published in 2013, by Inquiring Minds Productions.