Lavender Panthers & LGBTQ Politics in the Postwar Era

Historical Essay

by Colleen Greisch, 2022

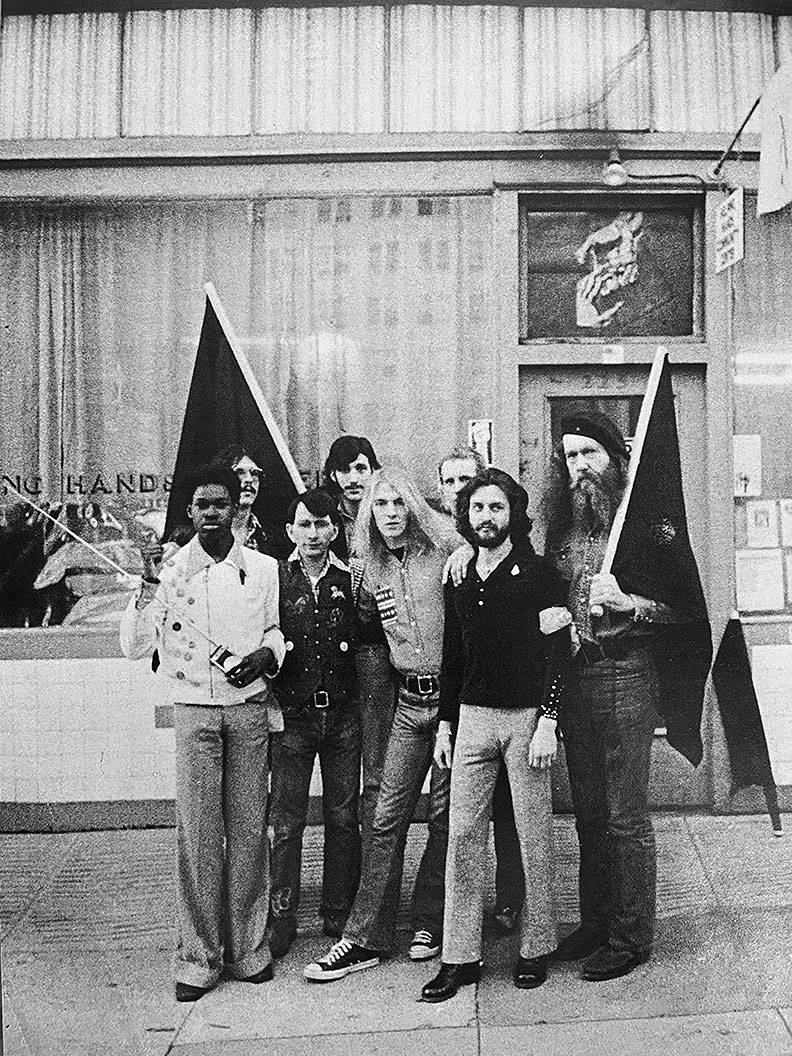

Lavendar Panthers, c. 1973.

Image: courtesy GLBT History Center

- “Nothing disgusts me more than a faggot on the sideline.”

- —Rev. Ray Broshears, leader of the Lavender Panthers

- “Nothing disgusts me more than a faggot on the sideline.”

The LGBTQ movement is often characterized as a successful movement that achieved significant gains in a remarkably short period of time. While the popular historical narrative is one of straightforward progress from the postwar period to the 21st century, recent LGBTQ scholarship exposes the reality as far more complex. As queer scholar Emily Hobson (2017) points out, postwar queer politics has been both diverse and divided; the movement has struggled with conflicting visions for change as well as periods of regression. The tension between homonormativity and gay radicalism is an especially significant thread that has continuously woven itself throughout the history of LGBTQ politics and activism. Lisa Duggan defines homonormativity as “a politics that does not contest heteronormative assumptions and institutions but upholds and sustains them, while promising the possibility of a demobilized gay constituency and a privatized, depoliticized gay culture anchored in domesticity and consumption” (Duggan, 2003). Leftist gay radicalism, on the contrary, is characterized by efforts to connect gay liberation to the liberation of women, people of color, and decolonization. Activists and organizations operating from a radical leftist framework view oppression as an issue of structural power, one that cannot be divorced from the systems of capitalism, patriarchy, white supremacy, and imperialism.

The early gay rights movement, known as the “homophile movement,” emerged during the Cold War. The Mattachine Society, founded in 1950, was one of the earliest gay rights organizations. A notable founder, Harry Hay, was a committed labor organizer and Communist party member who eventually resigned from the party because openly homosexual members were not allowed. The early Mattachine Society was shaped by Hay’s fervent Marxism and his push for a grassroots movement of gay people united in political action with other marginalized communities. However, amidst the Lavender Scare and the spread of an anti-communist left, Hay and other radical members were ousted from the Mattachine ranks and replaced with more conservative and homonormative-minded leaders who viewed presenting a wholesome image of gay life to straight America as the favored path forward. These leaders, mostly white and middle class, were not interested in aligning their struggles with those of women, gender-non conforming peoples, or the poor. Instead, they focused their efforts on privacy-based rights for individuals and discrimination protections in employment and the military.

In the 1960s, these conservative perspectives were disrupted as countercultural ideas and a radical sexual politics emerged. The emergence of a gay political consciousness included increased acts of rebellion against police and an understanding of state violence as a form of social control that linked gay politics to the struggles of other marginalized identities. According to historian Susan Stryker, the first known instance of collective militant queer resistance took place at Comptons’ Cafeteria on a hot San Francisco night in August of 1966. The Tenderloin District’s now famous riot against police brutality was led by transgender women, sex workers, and drag queens, and radically departed from the assimilationist tactics of the early homophile movement, contributing to bringing forth a liberation centered movement.

The liberationist years that followed were incredibly active with events like the Stonewall Rebellion, the Lavender Menace, and the founding of radical leftist groups such as the Radicalesbians and the Gay Liberation Front (GLF). The GLF and other liberation groups distinguished themselves from homophile organizations by opposing the Vietnam War, aligning with the Black Panthers, and critiquing state power. By 1972, however, the various chapters of the GLF had dissolved due to internal strife, state repression, and a broad decrease in radical political activity across the nation. Overall, the 1970s witnessed a shift in organizing towards a more reform-based and single-issue-oriented movement. Simultaneously, a small contingent of radical organizations still managed to grow; a contingent that would greatly influence the organizing strategies of the AIDS crisis in the following decade.

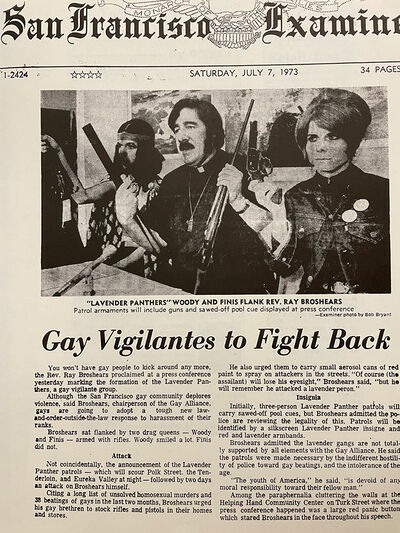

In the year 1973, within this shifting political climate, the first documented U.S. gay militant street patrol – the Lavender Panthers – was formed in order to protect the LGBTQ community from street attacks. Earlier that same year, a string of antigay murders in San Francisco had rocked the LGBT community, including the murder of the Gay Activist Alliance (GAA) member David Hart Winters. The 19-year-old was beaten unconscious and his body was left to be hit by a train on the former Sunset Tunnel streetcar tracks (Rolling Stone, 1973). Hardly anyone, including the police, took notice. When it came to the crisis of antigay violence, the glaring institutional neglect galvanized community activists to take matters into their own hands.

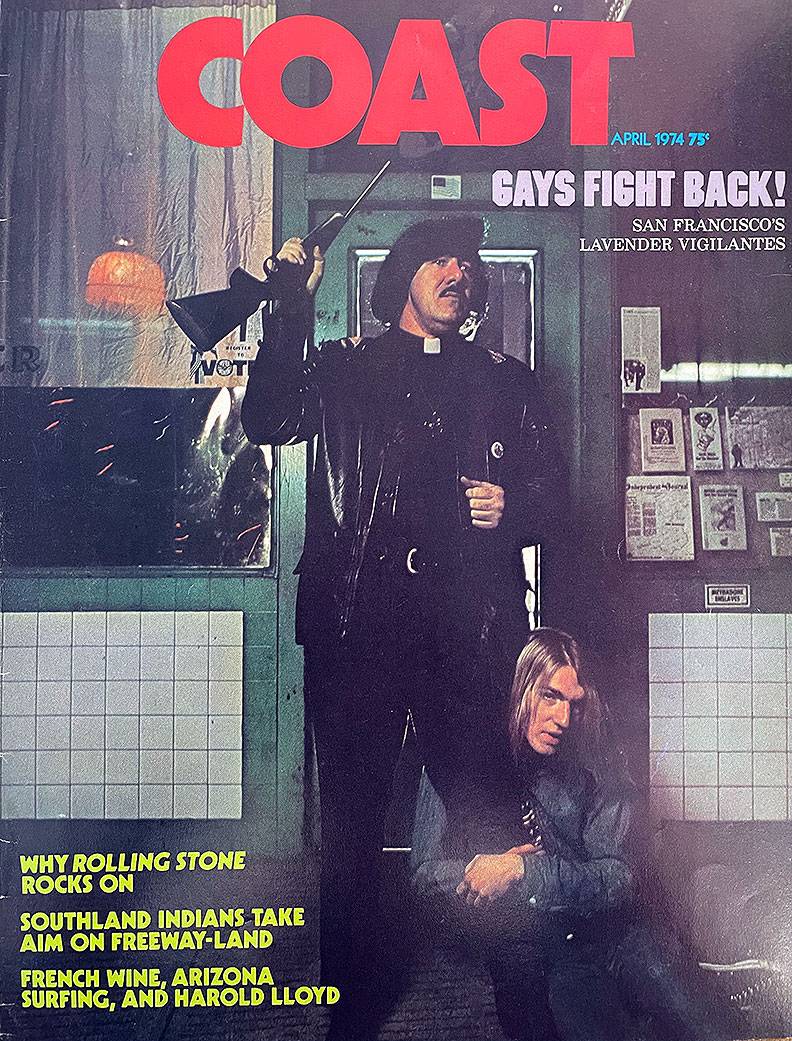

Courtesy GLBT Historical Society

The Lavender Panthers, originally called the Purple Panther Division of street people, were made up of a small group of vigilante queers who patrolled the streets in a worn-out VW bus armed with sawed-off pool cues, shotguns, and chains, prepared to interfere with anyone seen hassling or harming queers. The Lavender Panthers, whose name and logo sought to pay homage to the Black Panthers despite no reported alliance between the groups, were organized and led by Reverend Ray Broshears. Broshears, a controversial and idiosyncratic figure of San Francisco LGBT history, was a gay activist and clergyman who moved to San Francisco in the mid-1960s. Raised in Illinois and ordained in the Universal Life Church, Broshears went on to create his own style of ministry that sought to uplift those most ignored and oppressed by mainstream society. Throughout the 60s and 70s, he worked on the ground in the Tenderloin to advance the conditions of transvestites, sex workers, runaways, and queens. Broshears was responsible for founding the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) and helped create one of the first SF pride celebrations. He was also known for his temperamental and often combative personality, as well as having a penchant for performative publicity. This was often used against him by those in the community who opposed the Lavender Panthers and derided the group as an instrument of Broshear’s self-aggrandizement.

The Lavender Panthers’ street patrols were not designed to watch for police abuses, as was the case with the Black Panthers’ street patrols in 1966, but were instead directed towards straight “punks.” These punks were not explicitly racially identified by the Lavender Panthers but were often Chicano, Black, or Chinese. This racial tension is not often documented in stories about the Lavender Panthers, but it speaks to the disconnect between them and other liberationist groups operating at that time. Whereas other groups were formed around multi-issue organizing including coalitions against state violence, the Lavender Panthers (and the GAA) operated from an explicitly gay and religious ethos. The Lavender Panthers were unique in the sense that they angered the gay establishment on account of their militant and anti-assimilationist tactics while simultaneously being dismissed by other radical leftist groups who were turned off by Broshear’s zany religiosity and what they viewed as a hierarchal and myopic agenda.

courtesy GLBT Historical Society

The Lavender Panthers, regardless of their position in the postwar gay political sphere, were first and foremost a community group with high hopes to combat the intolerance of the era and the hostility of the San Francisco police force. How successful they were in actually preventing or intervening in antigay violence is debatable, but they did succeed at providing other significant services to the community such as free self-defense training and a citizen maintained log of hate crimes. The group also included trans women and gender noncomforming peoples at a time when these populations were shunned by other activist groups. The Lavender Panthers disbanded in 1974 due to what some accounts say was unrelenting police surveillance and intimidation. Other accounts suggest that the group dissolved due to more wide ranging opposition and a fading interest from the media. At a final press conference on May 22, Rev. Ray Broshears defended the group by declaring he had received 318 letters of support from people around the country and that the Lavender Panthers “contributed much in the way of personal safety awareness” of people living in the Tenderloin. As the first ever documented militant gay street patrol, the Lavender Panthers would go on to influence future (and similarly controversial) gay street patrols that came into existence in the 1990s such as the Butterfly Brigade and SMASH.

Note: At the onset of gay liberation, “gay” referred not just to gay men but also to lesbians and trans/gender nonconforming people. Increasingly, however, these groups operated in parallel instead of under one umbrella.

Works Cited

Duggan, Lisa. The Twilight of Equality? Neoliberalism, Cultural Politics, and the Attack on Democracy (Beacon Press, 2003), 50.

Hobson, E. LGBTQ Politics in America since 1945. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History. 9780199329175-e-234 Retrieved 14 Jul. 2022.

Pasulka, Nicole. Ladies in the Streets: Before Stonewall, Transgender Uprising Changed Lives. NPR, ewall-transgender-uprising-changed-lives. NPR, 5 May 2015.

Rolling Stone Magazine, Issue 144, September 27, 1973.