The Progress Club—1934 and Class Memory

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson, 1998

The piecards [paid union officials] took the hiring hall away from us by putting goons like “Johnny Loudmouth” in control of job dispatching. His specialty is to intimidate the guys up in age. It’s a way of destroying memory. We don’t write our history. Those guys are it.

—Hector Soromenho

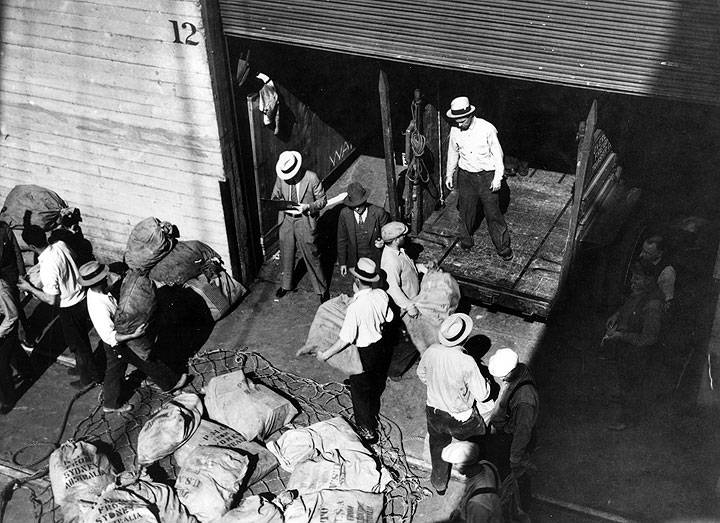

Longshoring evolved over many decades into a fluid, cooperative, mutually dependent labor process

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library]

The strategies used since the 1934 General Strike to overcome San Francisco’s working class have wrought profound changes in work, technology, and daily life. This process has been sold as “progress”—as in “you can’t stop it”—and has enjoyed explosive success on a global scale during the post-WWII growth of the world market. Progress conveniently masks changes in social arrangements, making them appear as “natural” results of technical and market rationality, rather than the self-serving moves of a powerful elite.

Progress unifies capitalist planners around shared values and assumptions, as if they were in the same social club (which they often are, literally, as well). Progress is also an ideological “club”—in the sense of “blunt instrument”—wielded against recalcitrant workers and uncooperative communities to ridicule opposition to corporate development plans. Progress as ideology has assured that all changes are both for our own good and, in any case, inevitable. Meanwhile, the forces behind progress have broken and rewoven the texture of human life at work and at home repeatedly over decades.

Progress brings modernized machinery; to accommodate new machines, work habits and production processes have been radically changed, reducing the human labor component of most jobs and making it easier to shift work from one place to another. These changes in turn have eliminated elaborate relationships based on shared cultures and artisanal knowledge. This kind of progress has also undermined organizations (like industrial unions) that grew during earlier moments in history (when there were different jobs and business structures, and the fight between workers and owners led to unions as a compromise).

A growing self-awareness and a working-class talent for wildcat strikes in the late 1930s and shook San Francisco’s controlling class to the core. The elite responded with a decades-long process to regain the upper hand in the balance of power. The forces unleashed by the Depression-era upheavals on the waterfront made San Francisco’s local class struggle a crucial staging area for reshaping ruling-class response. Ultimately, this long-term counter-offensive changed life, both at work and at home. What began as an effort to circumvent organized workers in San Francisco by regionalizing the local economy became a model for the globalization that has swept the world in the past quarter-century. San Francisco has been an important test site for our society’s most advanced techniques for improving and extending the control of capitalism.

Confronted by the full arsenal of ruling-class power over the last six decades, San Francisco’s once-vaunted labor movement at the end of the twentieth century has been reduced to whispering where it once roared. The local outcome of this old dance with capital is a restructured city economy. The once dominant waterfront is dead, replaced by a predominantly low-wage, non-union economy based on tourism, entertainment, shopping, eating, and financial and medical services. The working class, rarely identified as such anymore, is fragmented along racial and status lines, and increasingly stratified at work. New categories of white-collar technicians and professionals, while still wage workers, are far removed from the gritty industrial working class of the mid-century and earlier. Another third of the working population is consigned to drift from temporary job to temporary job, under constant pressure to improve and diversify their personal skills to offer prospective employers maximum flexibility.

Accelerated residential transience within and between urban centers has further fractured and atomized workers, largely destroying the long-term institutions and facilities that help city dwellers discover each other and enliven real communities. In today’s San Francisco thousands of homeless people eke out survival amid remarkable material abundance, while most of us work and shop in an invisible but “normal” isolation. Communities based on ethnic or national origins, neighbor- hoods, or occupations have been dispersed and worn down by several decades of urban redevelopment and economic modernization. San Francisco has a much different working population in the 1990s, doing different work, than it had half a century ago, with people living in much more expensive housing for shorter durations.

The exhilarating grassroots working-class culture that discovered itself in the strikes and organizing campaigns of the 1930s has been unmade and erased in the following half a century. How did 98-percent unionization of restaurants in 1941 (a union card in the window practically required to get steady customers) become the low-wage, temporary, non-union cappuccino bars, taquerías, pizzerias, chain stores, and dessert boutiques of today? How come no one thinks there is a working class, let alone that they are in it?! Our basic ability to see our lives as a collective rather than individual predicament has practically disappeared. How did this all happen?

When the Workers Rose

The 1920s was the decade of the “American Plan” in San Francisco, with the open shop and untrammeled business power calling the shots across the city’s economy. The well-financed Industrial Association, an entity formed to carry out a coordinated labor strategy among San Francisco’s largest companies, relentlessly fought every attempt by workers to regain lost wages, shorten working days (to eight hours), and organize independently.

Shipping magnate Robert Dollar (Dollar Lines, beneficiary of over $20 million in annual federal subsidies during the late 1920s to handle mail across the Pacific Ocean) illustrated the hardball tactics that propelled owners into the driver’s seat. Speaking to a National Association of Manufacturers meeting in New York in 1923, Dollar described a recalcitrant judge who refused to jail locked-out maritime workers in 1919:

We told him that because of his reluctance to prosecute we had found it necessary to form a vigilance committee and if the serious conditions along the waterfront did not stop at once, our first official act would be [to] take him and string him up to a telephone pole. . . . I can see that official yet. He could not believe we really meant it, so he said to me, “Mr. Dollar, do you mean that?” I answered, “I was never more earnest in my life.” My reply brought him to time [sic] and he at once promised to cooperate with us and he did. . . . (ILWU 1963)

It took many years, but by 1933 waterfront workers were again organizing independently. The June 1933 National Industrial Recovery Act provided workers “the right to organize and bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing.” Longshoremen quickly deserted the company union known as the “Blue Book” and rejoined the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA). The new union militants held a convention in San Francisco in February 1934 for all the International Longshoremen’s Association longshoremen along the West Coast. The workers met for ten days but excluded paid union officials as delegates. They resolved that no agreement could be valid unless approved by a rank-and-file vote. They demanded union recognition, union-controlled hiring halls to replace the humiliating “shape-up” (in which workers had to submit to nepotistic and corrupt bosses every morning to seek work), a raise in pay, a thirty-hour week, and a coast-wide agreement covering all U.S. ports. They also called for a waterfront confederation of all marine workers, including teamsters; rank-and-file gang committees to handle grievances instead of business agents; and opposition to arbitration, since it always led to defeat. They also sought to prevent the use of new technology (“labor-saving devices”) such as four-wheel wagons and the use of jitneys to pull two wagons at once. The shippers refused to negotiate, and in May 1934 the strike that would engender so many changes began.

Local business leaders failed to grasp the shifting balance of power that such a large, cross-occupation and well-organized rank-and-file strike could produce. William H. Crocker, grandson of the original “Big Four” railroad baron, said during the General Strike:

This strike is the best thing that ever happened to San Francisco. It’s costing us money, certainly. We have lost millions on the waterfront in the last few months. But it’s a good investment, a marvelous investment. It’s solving the labor problem for years to come, perhaps forever. . . . Mark my words. When this nonsense is out of the way and the men have been driven back to their jobs, we won’t have to worry about them any more. They’ll have learned their lesson. Not only do I believe we’ll never have another general strike but I don’t think we’ll have a strike of any kind in San Francisco during this generation. Labor is licked. (Nelson 1988)

Certain that brute force could win, as it had during the previous decade, San Francisco’s Industrial Association decided to force the issue after strikers had closed the port for two months. On July 3, 1934, using strikebreakers and the San Francisco Police Department, they forcibly moved cargo from the strike bound port to warehouses a few blocks inland. Violent confrontations between thousands of strikers and police exploded along the southeastern slopes of Rincon Hill and the waterfront. After a holiday truce, July 5, 1934, became memorialized as “Bloody Thursday” when two men died and scores were hospitalized in day long skirmishes and hand-to-hand combat all over the waterfront. The brutality of the police shocked the city and the country.

Strikers face off against police on July 3, 1934 near Pier 28 on the southern waterfront.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

A silent funeral procession of over 40,000 filled Market Street a few days later, and by July 13 a General Strike was spontaneously unfolding in San Francisco and around the Bay Area. The Central Labor Council, which had denounced the maritime strike leaders as communists in late May, scrambled to head off the General Strike by creating a Strike Strategy Committee, an effort characterized by activist Sam Darcy as an effort “to kill the strike, not to organize it.” (Brecher 1972)

At 8 a.m. on Monday, July 16, the San Francisco General Strike officially began, affecting around 150,000 workers around the Bay. But it had already been rolling along for a few days by then. Between July 11 and 14, over 30,000 workers went out on strike, including teamsters, butchers, laundry workers, and more; by July 12 twenty-one unions had voted to strike, most of them unanimously.

2,500 national guardsmen occupied the waterfront during the General Strike

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

The General Strike began to weaken almost as soon as it officially began. The National Guard occupied the waterfront and violent attacks by vigilantes (off-duty police and hired thugs, coordinated by the Industrial Association) occurred all over San Francisco. The conservative Strike Committee authorized so many workers to go on working that they dramatically undercut the movement. On the very first day, they allowed municipal carmen (running the streetcars) to return to work, ostensibly because their civil service status might be jeopardized. The chairman of the Labor Council and the Strike Committee was Edward Vandeleur, who was also president of the Municipal Carmen and had opposed the strike from the beginning. The ferryboatmen, the printing trades, electricians, and telephone and telegraph workers were never brought in on the strike. Typographical workers and reporters continued to work on newspapers that spewed forth anti strike propaganda. Labor Council leaders even went so far as to issue a work permit to striking sheet-metal workers to return to their jobs in order to repair bullet-riddled police cars.

President Franklin Roosevelt stayed officially aloof from the strike, his Labor Secretary Frances Perkins cabling him that the General Strike Committee of Twenty-Five “represents conservative leadership.” On July 19 the General Strike Committee narrowly voted to end the strike. On July 20, the Teamsters voted to return to work, fearing that the Mayor’s Committee of 500 and the Industrial Association would put strikebreakers on all the trucks in San Francisco and leave the Teamsters without any jobs. This was the end for the Longshoremen and Seamen’s strikes along the waterfront. By July 31, they ended their strikes and accepted federal arbitration, which ultimately led to partial victories on wages and hours, but the key issue of union control over hiring halls was settled with a formula that allowed for joint management of hiring halls with the shipping companies. Since the unions got to pick the dispatchers, they enjoyed control in fact if not by contract. The 1934 General Strike put a lethal dagger into the heart of fifteen years of “American Plan” propaganda (the 1920s’ version of anti-union, anti- communist, pro-American patriotism) and open shop conditions.

A Sleeping Giant Stirs

Daily life changed dramatically after 1934. In spite of a desultory and ambiguous conclusion to the 1934 upheaval, it still led to an extended period of worker activism, unionization, and a profound shift in power relations in most of the city’s workplaces, creating and reinforcing a broad sense of camaraderie and solidarity among the working class. Crocker’s gloating claim that the strike would “lick labor” and end all strikes could not have been more wrong. Workers across most occupations discovered the power of strikes, and by the late 1930s unions were becoming entrenched in most parts of San Francisco’s economy.

Each year between 1927 and 1933 saw fewer than ten strikes in the Bay Area, but after the 42 strikes involving over 100,000 workers in 1934, the rest of the 1930s saw an average of over 60 strikes per year, involving about 25,000 workers annually for about a half-million lost work days per year.

On San Francisco’s contentious waterfront the longshoremen gained practical control over the allocation of work. Worker-elected dispatchers rendered individual employers irrelevant by establishing a remarkably egalitarian “low-man-out-first” system to share the available work. (This system, which equalized opportunity to work but not necessarily income, was developed by longshoremen in San Pedro and copied by the San Francisco local. (Weir, interview with author, 1997)) Moreover, the daily rhythm of the “four-on, four-off,” along with numerous restrictive work rules spread the work out even further while maintaining a pace of work set by the longshoremen themselves. Offshore unions of sailors and others gained complete control of their own hiring hall after the violent waterfront strike of 1936.

The ILWU itself pursued an organizing strategy it called the “March Inland.” Warehouse workers were ready to join. Joe Lynch told interviewer Harvey Schwartz: “You had commercial warehouses strung along the waterfront from the Hyde Street pier over to Islais Creek; then you had cold storage warehouses; behind those you had mills, feed, flour, and grain; behind those you had grocery—big grocery, with 1500 people—and that’s the way they organized. Gee, it was terrific. Then came hardware, paper, and the patent drug industry, and the coffee, tea, and spice in ’37. Liquor and wine came in ’38. Then it was a mopping up operation after that. By World War II, the union had under contract, either wholly or partially organized, 46 different industries in warehouse, distribution, production and processing.”

Another worker, Brother Hackett, told Schwartz:

After the 1936–37 strike everybody organized. You went around the neighborhood on your lunch hour, found somebody havin’ lunch, and started talkin’ to ’em. If they didn’t belong to a union, you asked ’em what wages they were getting. When you found out how little they were being paid, you’d say, “We just joined the Warehouse Union and went out on strike for a lousy couple of months, and doubled our salary.” The guy’d say, “Just lead me to it.” See, there was a tremendous surge then. We had a meeting every week. There was always fifteen, fifty, or a hundred to two hundred people being sworn in. The people were just waiting in the weeds for somebody to hit them with a stick. It was just like a great awakening or a crusade.

With the ILWU setting the example, unionization of workers in other industries continued through the 1930s. The culinary union made rapid gains during this period. Waitresses Local 48 organized first in restaurants patronized by union clientele, spread its drives to restaurants outside working-class neighborhoods, swept up cafeteria, drugstore, and tea-room waitresses, and then included waitresses employed in the large downtown hotels and department stores. By 1941, waitresses in San Francisco had achieved almost complete organization of their trade, and Local 48 became the largest waitress local in the country.

Culinary organizers credited the new climate of solidarity:

There is a much better spirit of cooperation than formerly and the Culinary Workers have profited from it. We are indebted to the Maritime Unions and . . . in fact all the unions pull with us whenever we go to them with our troubles, thus our brothers did not give their lives for nothing. (Cobble 1991)

Workers enthusiastically took more power in worksites all over town, utilizing innovative tactics from sitdowns and occupations to costumed picket lines, theatrical demonstrations, and clever grassroots informational campaigns. After enduring hundreds of short wildcat strikes during the 1930s, employers naturally began to look at the bigger picture. How could the chokehold of organized labor be bypassed, if not defeated? The foundations for a capitalist counterattack had already been laid, even as workers took more daily control than they’d ever had before.

The Owners Regroup

Most workers flocked to the new CIO industrial unions, but less well remembered is the extent to which employers, too, saw an answer to a restive and increasingly assertive working class in the new unions. A number of large U.S. companies, including General Electric and U.S. Steel, embraced the new centralized unions of the CIO to control unruly, rebellious industrial workers. The romantic lens through which leftist historians have viewed the 1930s has underplayed the conflicting forms of working-class organization that fought each other in that tumultuous decade. Rank-and-file democratic structures created by strikers were generally dismantled as they entered the new industrial unions, and power was transferred from the shop floor to the union offices.

From 1937 through the 1950s, when organization among San Francisco restaurants remained close to 100 percent, many employers willingly complied with this system of union-sponsored industry stabilization and cooperation. Employers who failed to recognize the good business sense of unionization . . . faced increasing pressure through the [labor] council’s “We Don’t Patronize” list. Few employers could withstand the business losses of withdrawn union patronage when approximately one-fifth of San Francisco’s entire population belonged to a labor organization. (Cobble 1991; emphasis added)

In The Turbulent Years, Depression labor historian Irving Bernstein recounts how in 1937 San Francisco’s “leading businessmen formed the Committee of Forty-Three, hoping to persuade the unions to join in a program to stabilize labor relations.” Though labor refused at first, the Committee soon became the Employers’ Council, whose purpose was “the recognition and exercise of the right of the employers to bargain collectively.” (Zerzan 1977) The stabilization offered by union contracts inspired most San Francisco business owners in 1938 to join the San Francisco Employers’ Council, which promoted industry-wide, multi-employer bargaining. By 1948, the single-employer contract had become the exception, with over 75 percent of all union workers falling under “master” industry-wide contracts. (Selvin 1967) But a stable, adversarial union still makes demands and puts some constraints on the power of business owners. With the benefit of a half-century of hindsight, we can see that the pragmatic accommodation with unions was not a permanent change but a temporary tactic to gain time for a much grander strategy.

Ruling-class planning in San Francisco faced an entrenched, self-confident, smart, historically savvy working class in pre-WWII San Francisco. World War II spurred cataclysmic changes worldwide, and war mobilization in San Francisco promoted a regionalization of industry and an influx of new workers, altering for- ever the composition and residential distribution of the area’s working class. Regional planning, underway since the 1920s, combined with New Deal infrastructural investments to cross the bay with new bridges and surround the region with new highways. In regionalizing the Bay Area economy, planners moved shipping to Oakland, heavy industry to the north and to the East Bay, while high-tech industries grew around university enclaves and military bases. Regionalization was pursued for its perceived economic benefits, but its purpose in the heated battle for the control of work was clear to some.

In 1948, at a Commonwealth Club debate, a San Francisco banker said:

Labor developments in the last decade may well be the chief contributing factor in speeding regional dispersion of industry. . . . Large aggregations of labor in one [central city] plant are more subject to outside disrupting influences, and have less happy relations with management, than in smaller [suburban] plants. (Mollenkopf, 1983)

Postwar economic planning expanded the logic of regionalization to globalization, under U.S. domination. San Francisco’s role was to be a corporate headquarters, overseeing a far-flung network of production and distribution. This was well underway soon after WWII, further encouraging the deindustrialization of the city. For example, banking employment in San Francisco during the 1950s more than doubled, while maritime work fell by 25 percent. (Mollenkopf 1983) Blue-collar, unionized work was under calculated assault as the logical companion of much larger dynamics in the marketplace.

Racial tensions were exacerbated by thousands of newly laid-off black shipyard workers, many of whom had come to the Fillmore and Hunters Point (as well as Oakland and Richmond in the East Bay and Marin City in Marin County) during the war, and now competed with white workers for unionized industrial jobs. After the strike wave of 1946 (the largest in U.S. history until then, with over 2 million workers taking part) President Truman and the Democrats in Congress joined with the Republican majority to attack the workers’ movement. The 1947 Taft-Hartley Act constricted the legal space in which unions had flourished, outlawing effective tactics used by workers to gain power in negotiations and on the job, including secondary picketing, which can spread strikes across the boundaries of occupation and industry. Taft-Hartley also mandated that union leaders sign declarations that they were not communists. Cold War hysteria swept the union movement, driving the most radical and militant workers underground if not out of work.

The “1934 men” along San Francisco’s waterfront were subjected to unrelenting red baiting, most visibly in the multiple prosecutions and attempted deportations of ILWU president Harry Bridges, because of his always-denied and oft-alleged communism. (Party membership notwithstanding, he was a close follower of the political “line” of the Communist Party of the USA, which was in turn a close follower of Stalin’s Soviet Union.) The coercive mistrust and paranoia produced by the anti-Communist crusade of the 1950s eroded much working class spontaneity. The powerful nationalism of WWII and then Cold War America was mobilized against suspected radicals and assorted malcontents and deviants. In the case of San Francisco’s waterfront, a quasi-militarization that had started during WWII was reinforced and stepped up by an August 1950 Congressional mandate to use the Coast Guard to screen out “security risks” on the docks and ships. Men who appealed their abrupt firing were shown no evidence incriminating them. The Coast Guard would simply insist, “you tell us why you think you’ve been classified a security risk.” (Larrowe 1972)

Automating Intimidation

Containerization is the technological underpinning of the global economy. You can bet your sweet ass that if all them transmissions was being hand- handled and put on a pallet board and sent ashore, rather than 20 tons of transmissions in a goddamned container box, transmissions’d still be built in Detroit. The container has been the physical means of exploiting cheap labor throughout the world.

—Herb Mills, former ILWU Local 10 official (Mills, 1996)

The longshoremen under Harry Bridges stood at the radical edge of unionism in 1934. Waterfront workers maintained a work culture that was powerfully resistant to speedups and increased exploitation for twenty-five years. But after that period, affectionately remembered as “the golden age,” Bridges and his colleagues began to accept the “inevitability” of capitalist modernization. By the late 1950s, the emergence of new technologies associated with the conversion to trucking and highways (that is, containers) threatened control over work by the unionized workers.

Typical longshoring work in the 1940s.

Photo: ILWU Archive

Containers stacked at Port of Oakland, 2008.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Longshoring was once a complicated job requiring great coordination and cooperation among agile, quick-thinking crews of strong men. The job changed from day to day, from dock to dock, ship to ship, and cargo to cargo. It took many finely developed skills to quickly load and unload a ship before the widespread adoption of containers. A list of typical cargoes, each packed for shipping in its own way, gives an idea of the variety facing the pre-automated longshoreman, and when you add the hundreds of different ships of all shapes and sizes, the complexity and variety increases proportionately. Typically, cargo consisted of differing sized crates and packages of varying weights shipped by small manufacturers. . . . Larger crated shipments of such variously sized and weighted items as machines and machine parts, furniture, glassware, dishes and ceramics, sports equipment, clothing, and relatively exotic or “specialty” food products; still larger and variously packaged shipments of all sorts of food—from 25 pound boxes of Norwegian sardines through 100 pound barrels of Greek olives—were common. So, too, were shipments of wines, beer, liquor, cheeses, teas, coconut and tapioca, tropical fruits, candy, cookies, and specialty desserts, plus a wide variety of canned goods. A host of industrial products—from ingots of copper, through sheet and bar steel, pipe and rails, to steel pellets, corrugated metals, and fencing—were standard. The number of sacked or bagged goods was leg- end: cement, flour, wheat, barley, coffee, and all sorts of nuts and dried fruit. Then, too, there were the offensive sacked cargoes which were worked at a penalty rate of pay, e.g. animal bones and meat scraps, blood and bone meal, fish meal, coal, lime, phosphates and nitrates, lamp black and soda ash. Baled goods were also common—cotton, rubber, rags, gunnies, jute, pulp and paper. Deck loads of lumber and/or logs, or creosoted pilings, utility poles, or railway ties, of farm and construction equipment and all sorts of commercial vehicles were almost always worked. (Mills 1976)

With the advent of the container, all that variety was buried in an endless stream of 20-ton boxes. In 1960, the famous Mechanization and Modernization Agreement between the ILWU and the Pacific Maritime Association accelerated the process of capitalist restructuring that killed San Francisco’s commercial port and radically reshaped San Francisco’s economy. The ILWU reaffirmed the traditional U.S. trade union bargain: money (raises, pensions, bonuses) in exchange for control over work—its organization, its purpose, its use of technology. The owners got the long-sought power to change the structure of work and, by co-opting the longshoremen, to lay the essential foundation for the globalization of production.

In one fell swoop, the detailed work rules built up over twenty-five years of work stoppages, “quickie” strikes, hours of negotiations and scores of arbitration decisions were discarded. Gone were the double handling of cargo, the job “witnesses”—men who performed no work but only watched, manning scales, first place of rest, and so on. The employer was free to install any machines or methods he chose. The work, however, must be safe. The work of the individual longshoremen could not be made more “onerous.” (Selvin 1967)

Slingload weights increased and became derisively know as “Bridges Loads.” (Weir 1967) The M&M Agreement also contractually reinforced the old categories of worker seniority, officially denoting a three-tier hierarchy: “A” and “B” and “casual.” The B men are a permanent and regular section of the work force who get the pick of the dirtiest and heaviest jobs that are left over after the A, or union, men have taken their pick. After the B men, casuals hired on a daily basis get their turn at the remainders. The casuals get none of the regular fringe benefits. . . . [The B men] pay a pro-rata share of the hiring hall’s operating expenses, but have no vote . . . they sit in a segregated section of the [union] meeting hall’s balcony. . . . (Weir 1967)

Stan Weir organized a group of eighty-two B men who were briefly upgraded to A status (fulfilling a long-standing union promise to them) but were abruptly kicked back down to B status the very next day after the personal intervention of union president Harry Bridges. It’s a long, tangled, and much-disputed tale, but Weir argues that the real lesson of this saga was to strike fear into the A men, demonstrating that their brothers, sons, and friends were subject to the capricious whims of the union leadership if they wanted a steady union job on the waterfront. (Weir 1997) The solidity of a waterfront job was only as good as one’s loyalty to the Bridges regime. (It should be noted that some loyal ILWU stalwarts vehemently deny this version of events and insist that Stan Weir is all wrong.)

In 1963, in collusion with the employers [Bridges] led the Kafkaesque purge that expelled 82 [B men] from the waterfront jobs they had held for 4 years. (Over 80% of the 82 are Negroes.) They were tried in secret. The charges against them were not revealed. Their number, but not their identities was made known to ILWU members until after they were fired. [The discharged workers had no right] to counsel, to produce witnesses, to know the charges and to formal trial prior to judgment or sentencing. . . . Bridges’ witchhunt methods and double standards make the bureaucratic procedures used to expel his union from the CIO. . . . bland by comparison. (Weir 1967)

Bridges refused to concede anything to the dissidents, of whom Stan Weir was the most visible and outspoken. Seventeen years in various courts ultimately led to ILWU victory. Meanwhile, the ILWU carried on its “business as usual,” while many of the fired B men never recovered, their resulting despair leaving many broken lives and homes in its wake. (Weir, author’s interview 1997)

Spurred on by the Mechanization and Modernization Agreement, worklife on the waterfront was changing rapidly in the early 1960s. The M&M contract was renewed in 1966, the job security clause being dropped since the Vietnam War was keeping everyone on overtime anyway. A new clause was added, however, known as “9.43.” It allowed shippers to hire longshoremen directly to be their “steady men” running their expensive and “complex” new cranes.

The longshoremen were divided on the owners’ demand for “steady men” to run their cranes. The older workers accepted at face value the owners’ assertion that running these big container cranes was a highly skilled activity requiring special training and skills. The younger workers soon figured out that it was “no big deal.” In fact, the new longshoring was considerably less skilled than the dangerous and varying work of loading and unloading ships in the pre-container era.

The ILWU severely weakened itself when it acquiesced to dividing the workers between those directly employed by the shippers as “steady men” and those regular longshoremen who continued to get work assignments through the union-controlled hiring hall. The almost sacred institution of the hiring hall, won at such great effort in the 1930s, withered as a consequence of this adaptation to “progress.” The longshoremen’s self-managed work-allocation system based on the hiring hall was outflanked by automation, which drastically reduced the number of workers needed. The shippers pushed their new edge further by insisting on choosing an elite group to be steadily employed, leaving union stalwarts with sporadic and insecure work assigned by the hiring hall. The economic advantages of becoming a 9.43 man (guaranteed full time hours and higher pay) were irresistible to many, and divisions soon grew within the union.

After eleven years of M&M, longshoremen struck in 1971. Rank-and-file activists were mobilized against allowing “steady men” to work the big cranes (versus those dispatched daily from the union hall), while Bridges and the union leadership focused the demands on who would be allowed to “stuff” containers and a wage increase. President Nixon’s use of the Taft-Hartley Act failed to produce a settlement (96% voted to strike at the beginning, and 92% voted to continue the strike after the Taft-Hartley injunction), but the strike’s resumption after the mandated 60-day cooling off period failed to halt the use of new waterfront technology and its consequent division of labor. The strike lasted 135 days, but the union won only modest wage increases and little else. Left for arbitration was the contentious question of the 9.43 men, and the arbitrator’s decision didn’t alter the clause or the rights of management to divide the workforce.

Pier 80 in San Francisco was modernized for container shipping, but too little too late. By the time the Port of San Francisco gave up on the Lighter Aboard Ship system (the betamax to the VHS of containers) most shippers had relocated to the state-of-the-art facilities in Oakland.

Photo: Chris Carlsson, 2010

There hasn’t been another big strike on the West Coast since 1971. Former Local 10 secretary-treasurer Herb Mills thinks the 1971 strike was undercut from within by Bridges and the International leadership at the time. (Mills 1996) He says the damage done by 9.43 and the failure of the ’71 strike has divided and weakened the workers a great deal. In fact, during the 1996 coastwide contract negotiations, the rank-and-file of the two largest locals (Local 10 in San Francisco, and Local 13 in San Pedro/Long Beach) rejected a contract proposal because it called for mild restrictions on steady men’s ability to collect tens of thousands of dollars in “side deals” with the shippers. The same contract was passed on the second try after a full-court-press campaign by the union’s top leaders. In any case, the labor relations deal that prevails on the Pacific Coast has allowed container tonnage to quadruple since 1980, while the number of work hours has remained constant for a workforce that has been reduced over 20 percent. (Pacific Maritime Association 1995) Today’s longshoreman is a well-paid worker who can easily afford an upper-middle-class lifestyle, but there are only about 9000 longshoremen on the entire West Coast. The hiring hall is no longer the unifying institution it once was, and even if you could interest longshoremen in the social/political reasons for maintaining it, cell phones and modern telecommunications have made a central dispatch hiring hall obsolete. The special culture that longshoremen created at such sacrifice and with such imaginative brilliance has been broken. The power that once so intimidated San Francisco’s rulers and planners has been bought off and made manageable by the apparatus of unionized collective bargaining, modernization and, as we shall see, co-optation.

The Home Front

Redesigning work to disconnect workers from their power was only part of the picture. After WWII, San Francisco’s leaders faced an urban landscape full of both physical and social obstacles. Whole neighborhoods had to go—community stability had become an obstacle to rapid economic growth. The story behind several decades of “urban redevelopment” in San Francisco reveals a second front in our local class war. “Progress” was as readily invoked to justify evicting thousands while bulldozing whole neighborhoods as it had been to dismantle decades of workers’ power on the job.

It is not accidental that the San Francisco neighborhoods most skilled in organizing, with the most active memory of how improvements were actually achieved, were the same neighborhoods that experienced the wrecking ball of redevelopment. Redevelopment targeted neighborhoods where relatively coherent subcultures within the working class flourished. (I speak of the predominantly African American Western Addition, the Italian produce district, and the South of Market single-room-occupancy hotels that housed thousands of retired workers who had participated in the great upsurge of the 1930s.)

The wrecking ball first cleared the old Italian Produce Market to make way for the Golden Gateway apartments and the eastward thrust of the Financial District to the bay in the early 1960s. This project also led to the demolition of the old Alaska Fishermen’s Union building between Commercial, Clay, the Embarcadero, and Drumm. With its demise the waterfront workers lost a vital social center that had served them for decades (the ground floor had housed the longshoremen’s hiring hall, and several other maritime unions had offices there). Then the Geary Boulevard corridor, known in Redevelopment-ese as Western Addition A-1, cleared a two-block corridor westward from Cathedral Hill through the heavily populated Fillmore District. By mid-1967 the Western Addition A-2 plan had been made public and was well underway, removing over a thousand old Victorians in the Fillmore District and displacing over 10,000 African Americans in the process. Further redevelopment plans targeted the South of Market, Chinatown, and Mission Districts.

By the late 1960s, citizens groups were mobilizing in every neighborhood against redevelopment. The 1968–1969 Student/Faculty Strike at San Francisco State galvanized a whole generation of young activists, many of whom threw them- selves into the blossoming neighborhood redevelopment and housing struggles around the I-Hotel, Chinatown, the Mission, South of Market, and the Western Addition. In the Western Addition, community opposition came together in the Western Addition Community Organization (WACO), while in the South of Market TOOR (Tenants and Owners in Opposition to Redevelopment) arose. (Hartman 1984) Thousands supported the ten-year struggle to save the I-Hotel, the last remnant of a once lively stretch known as Manilatown.

Justin Herman, head of the Redevelopment Agency, took a swing with “old reliable,” the progress club, when he angrily denounced WACO as a “passing flurry of proletarianism,” which was trying to “turn back the clock.” (Mollenkopf 1983) But the mobilized, politicized community organizations, in some cases fused with the Black and Brown Power movements of the 1960s, could not be stopped by bureaucratic scorn alone. The “redevelopers” had to gain legitimacy to proceed with their plans. They used trusted labor leaders to create the appearance of a balanced, objective consensus for progress and redevelopment.

Co-optation

Largely supporting the pro-growth consensus of the early 1960s, union leaders were seen by ruling elites as reasonable men. Joe Alioto (head of the Redevelopment Agency himself in the mid-1950s) consolidated the integration of the big unions in town when he won the mayoral election in 1967 by building an old-style political coalition of big business and big labor with overt patronage. After winning the election with strong union support (major campaign supporters were Laborers Local 261, which was 65 percent black and 25 percent Latino, and ILWU Local 10, which was 70 percent black), Mayor Alioto appointed Harry Bridges to the Port Commission. He appointed Stanley Jensen of the Machinists Union and Joe Mosely, an African American dispatcher in the ILWU, to the Redevelopment Agency, Hector Rueda of the Elevator Construction Workers Union to the Planning Commission, and Bill Chester, another black ILWU official, was made president of BART.

Former ILWU clerk Wilbur Hamilton, an African American pastor with strong roots in San Francisco, was appointed to the Redevelopment Agency in 1968 and soon got the job of project manager for the Western Addition A-2 project, the Agency’s largest project. Hamilton gave a black, pro-labor face to the essentially white racist “slum clearance” plan devised in the boardrooms of downtown San Francisco.

The unions already had a symbolically important role in the Democratic Party and the pro-development consensus. Jack Shelley had headed the San Francisco Labor Council in the 1950s before he went to Congress, and had become mayor in 1963. During his tenure he led the fight for the Panhandle–Golden Gate Park Freeway. His administration attempted to straddle the widening gap between the old blue-collar city and its ascendant incarnation as a corporate headquarters.

As social movements evolved through the upheavals of the 1960s and against the background of the permanent (“cold”) war, organized labor became an aggressive agent of the capitalist order. Unions supported anything that seemed to “create jobs,” leading the charge for San Francisco’s absurd and finally truncated freeway plan, as well as uncritically supporting Manhattanization and “redevelopment” of the residential neighborhoods in which workers lived.

In the South of Market, this pitted the once-vibrant and class-conscious unions against many of their own retirees during the fight over the Yerba Buena Center. Peter Mendelsohn, of the Tenants and Owners in Opposition to Redevelopment (TOOR), describes how the unions went after people fighting the Yerba Buena Center:

They lined up all the unions against us. They went and got all the leaders. George Woolf sent a letter to Harry Bridges, asking Bridges to hear our side. We told him, “you’ve heard Redevelopment’s side, now we’d like you to come down and hear our side.” . . . It was guys like George Woolf and me who went out and raised money when they accused him of being a communist and tried to deport him. We were two of the main guys to defend him. . . . Harry Bridges’ answer to our letter was “I heard Redevelopment’s side, and Redevelopment’s side is good enough for me. I don’t want to hear your side.” If the unions supported us, this could never have happened. But the unions are bought off. (Resolution Film Center 1974)

In fact, the ILWU got a choice redevelopment property on Franklin Street atop Cathedral Hill, where the Harry Bridges Memorial Building now stands, home to the union, its library, and its pension fund. Individual longshoremen got homes in co-op apartments built by the ILWU pension fund and the Redevelopment Agency in the Western Addition, and the Port Commission made available a South Beach lot for the ILWU’s Clerks Local 34. This is not to insinuate that any corruption was necessarily involved. Rather, this kind of deal-making is the quintessence of modern capitalism’s ability to propel itself, absorbing and redirecting oppositional movements.

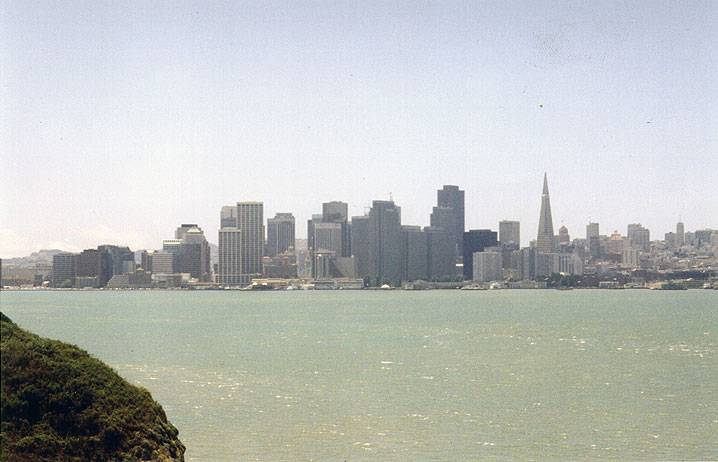

San Francisco skyline from Treasure Island in 1997, after decades of redevelopment and urban re-engineering by the local business and governing elite.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Port of San Francisco. Once-bustling piers lie dormant in the shadow of San Francisco's new economy, the corporate headquarters of the Manhattanized financial district.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Such co-optation contributed a great deal to the decline of trade unionism as a political and economic force. At best, it represents an ironic complicity in breaking transmission belts of working class culture and memory; at worst, it is a classic case of selling out the class for narrow material benefits. Union leaders who accept appointments to facilitate the corporate agenda offer us a disheartening example of ignorance, naiveté, corruption, or all three.

Capitalist modernization and social control cannot be blithely attributed to compliant union leaders, manipulative corporate planners, or complacent and forgetful workers. Our epoch is one in which historical amnesia is the rule, not the exception. Compelling visions of a different way of life (not organized to serve the market) are invisible or absent. When workers become more solid and organized, capital either mechanizes and restructures, or moves (or both). Future workplace revolts will have to plan for this. The stunted, warped life we live as “economic factors” rather than as full human beings has been utterly normalized and removed from history or social choice. We chase the buck and pay our bills because . . . well, what else is there?

Trumpeting San Francisco’s special novelty glosses over the essential sameness of life in San Francisco and elsewhere. The world’s most powerful capitalists cut their teeth and sharpened their strategies and techniques in San Francisco. Our daily life is the living proof that they have succeeded. These days “sudden revolt” sounds like a perfume or a rock band, not an implicit possibility within our collective revulsion at what passes for life.

Nevertheless, San Francisco continues to produce the seeds of revolt. The famous liberalism and tolerance for dissent helps make room for new initiatives that would be more difficult to embark on elsewhere. The half-century process of disrupting and disorganizing working-class communities at work and at home cannot prevent the inevitable re-emergence of real opposition. A new opposition, especially one that grasps the powerful levers available at work, remains to be defined. Among the fragments of our daily lives we must discover a language that reinforces our shared experiences and discoveries rather than emphasizing their identity-based differences. An inspired revolt based on a certainty that life can be much better than this is buried beneath the surface of our atomized existence. Can a new vision of progress help bring it up? Or will the progress club continue to bludgeon our aspirations for liberation? During the coming period the next chapters in San Francisco’s epic class struggle will be written, hopefully in a radically new way.

References

Brecher, Jeremy. 1972. Strike! Boston: South End Press.

California, State of, 1940. Handbook of California Labor Statistics, Table 37: “Workers Involved and Man-Days Idle in Strikes, by Industry Group, California, 1927-1939” and Table 36: “Workers Involved and Man-Days Idle in Strikes, California, Los Angeles City and San Francisco Bay Area, 1927-1940”

California, State of, 1955, Handbook of California Labor Statistics 1953-1954, Table 54: “Number of Work Stoppages, Workers Involved, and Man-Days Idle, Major California Cities, 1941-1951”

Cobble, Dorothy. 1991. Dishing It Out: Waitresses and Their Unions in the Twentieth Century. Urbana & Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Hartman, Chester. 1984. The Transformation of San Francisco, New York: Rowman & Allanheld.

International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union, Information Dept. 1963. The ILWU Story. San Francisco, CA.

Kazin, Michael. 1987. Barons of Labor: The San Francisco Building Trades and Union Power in the Progressive Era. Urbana & Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Larrowe, Charles P. 1972. Harry Bridges: The Rise and Fall of Radical Labor in the United States. New York: Lawrence Hill & Co.

Lens, Sidney. 1974. The Labor War, New York: Anchor/Doubleday.

Mills, Herb, 1976, “The San Francisco Waterfront: The Social Consequences of Industrial Modernization, Part One: ‘The Good Old Days’... and Part Two: ‘The Modern Longshore Operations’” reprinted from Urban Life. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications: Beverly Hills

Mollenkopf, John H. 1983. The Contested City, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Nelson, Bruce. 1990. Workers on the Waterfront: Seamen, Longshoremen, and Unionism in the 1930s. Urbana & Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Pacific Maritime Association. 1995. Annual Report, San Francisco.

Quin, Mike. 1948. The Big Strike. Olema, CA: Olema Books

Resolution Film Center. 1974. “Redevelopment: A Marxist Analysis,” film, b&w, 95 mins.

Schwartz, Harvey, ed., July 20, 1995, The Dispatcher, “The March Inland,” quoting Joe Lynch in Part IX of the ILWU Oral History Project

Schwartz, Harvey, ed., November 20, 1995, The Dispatcher, “Rank and File Unionism in Action,” quoting Brother Hackett in Part XII of the ILWU Oral History Project

Selvin, David. 1967. Sky Full of Storm. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Selvin, David. 1996. A Terrible Anger. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press.

Weir, Stan. 1996. “Unions With Leaders Who Stay On The Job.” In “We Are All Leaders”: The Alternative Unionism of the Early 1930s. Edited by Staughton Lynd. Urbana & Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Weir, Stan. 1967. “USA—The Labor Revolt.” International Socialist Journal. April and June 1967.

Yellen, Samuel. 1936. American Labor Struggles. Monad Press. New York: 1974

Zerzan, John. 1977. Creation and Its Enemies: The Revolt Against Work, “Unionization in America” Rochester, NY: Mutualist Book

This article originally appeared in Reclaiming San Francisco: History Politics Culture, a City Lights anthology edited by James Brook, Chris Carlsson, & Nancy J. Peters (City Lights Books, San Francisco: 1998)