Politics of Business

Historical Essay

by William Issel and Robert Cherny

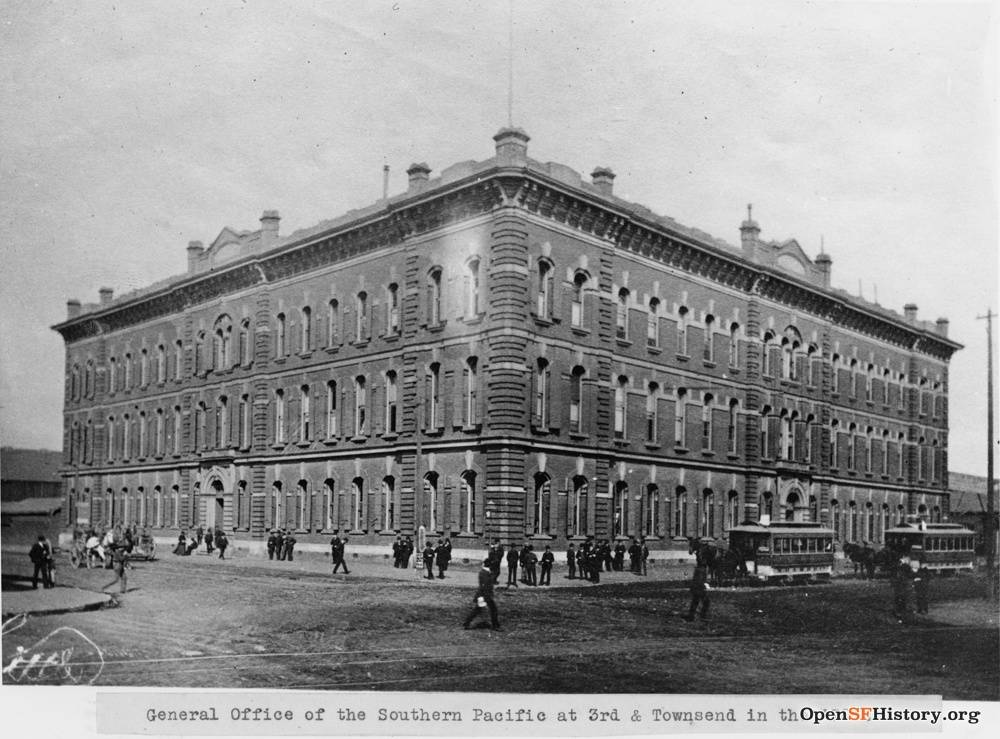

View northeast across the intersection of 4th and Townsend to Southern Pacific Railroad headquarters, 1870s.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp70.10271

The best-known partnership between government and private enterprise in the nineteenth century must surely be the construction of the transcontinental railways. The companies that became the Southern Pacific received more than 10 million acres of land, yielding a net revenue of $10 million over the first half-century of the line’s existence, in addition to federal bonds that netted nearly $21 million. The California state legislature, in 1864, assumed the interest on $1.5 million in railroad bonds, at 7 percent for twenty years, a commitment worth $2.1 million on its face. In 1863 and 1864, the legislature authorized three counties and the cities of Sacramento and San Francisco to provide further subsidies for railroad construction. The quartet in command of the railroad plunged deeply into the politics of legislative activity. Collis Huntington usually represented the line in Washington. Leland Stanford, president of the company, won election as governor in 1861 and served as head of the Republican party in California while Republicans in Congress ladled out generous subsidies for his railroad. He also proved willing to approve subsidy bills coming from the California legislature.(8)

Although the legislature authorized several counties and cities to subsidize railroad construction, voters in each had to approve the bond issues. In most instances, approval came routinely, but not in San Francisco. San Franciscans viewed the railroad with suspicion. A Sacramento-based corporation (headquarters did not move to San Francisco for another decade), headed by Sacramento merchants, it might break the position San Francisco held as chief entrepot to the Pacific Coast. In 1863, the city’s legislative delegation split five to five on the question of authorizing a $1 million bond issue to subsidize railroad construction. City voters, on election day, produced a majority in favor of the bonds, but opponents quickly claimed that the majority resulted from the activities of Philip Stanford, brother of the governor, who circulated among the city’s polling places distributing five- and twenty-dollar gold pieces and urging voters to approve the bond issue. When the Board of Supervisors refused to issue the bonds, the railroad went to court to claim its due, and the state legislature told the supervisors to compromise the claims. In June 1864, a committee of supervisors met with Stanford and agreed to pay $600,000. Even then, the mayor and the city’s fiscal officers refused to issue the bonds until ordered to do so by the state supreme court.(9)

After the mid-1860s, the railroad no longer sought direct cash subsidies, but other efforts to secure assistance continued. In 1868, a state senate committee recommended giving to the railroad nearly seven thousand acres along San Francisco’s southern waterfront, constituting total control over the area from Channel Street south to Point San Bruno in San Mateo County. The lands were all submerged, and the railroad was to pay about $100 per acre for them. This acquisition would provide the railroad with access to the San Francisco docks and with a location for the terminus of the transcontinental line. Furthermore, the railroad could fill in the submerged lands, construct a seawall, monopolize the southern waterfront, and simultaneously bar any other railroad from access to the city's piers. The proposal brought a storm of criticism from San Francisco business leaders, and a much-diluted compromise finally granted sixty acres for railroad terminals and a right-of-way. In the early 1870s, the city granted use of several streets as sites for track construction. Although the railroad failed to acquire control over the San Francisco waterfront, it did achieve a monopoly over the Oakland waterfront, and only intense opposition from San Francisco diverted a proposal to give the railroad complete control over Goat Island (now Yerba Buena Island).(10)

The railroad continued to invest large amounts of both time and money in political activities throughout the late nineteenth century. Huntington represented Southern Pacific interests in Washington whenever Congress was in session, and Stanford carried out similar duties in Sacramento. Huntington was remarkably candid in describing his attitude toward officeholders: “If you have to pay money to have the right thing done, it is only just and fair to do it.” He concerned himself with the composition of the San Francisco delegation to the House of Representatives, giving directions on one occasion that John K. Luttrell—whom Huntington characterized as “a wild hog”—should be defeated, preferably by denying him renomination. On another occasion he issued orders to defeat William A. Piper, whom he deemed “a damned hog” and “a scavenger.” By 1890, however, Huntington complained that “things have got to such a state, that if a man wants to be a constable he thinks he has first got to come down to Fourth and Townsend streets [Southern Pacific headquarters] to get permission.” Huntington committed himself first and last to the Southern Pacific, and party politics took second place with him. Stanford, by contrast, helped to organize the Republican party, ran for statewide office as a Republican in both 1857 and 1859 (before his involvement with the railroad), and won the governorship for that party in 1861. Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, Stanford kept his hand in slate politics, making campaign speeches and lobbying on behalf of the Southern Pacific. In 1885, he won election to the U.S. Senate.(11)

When Stanford took his seat in the Senate, he joined fellow Republican, fellow San Franciscan, and fellow businessman John E Miller. When Miller died a year later, George Hearst, another Nob Hill resident (albeit a Democrat), replaced him. During the mid-1880s, San Franciscans held not just the two California Senate seats but also one from Nevada. In 1874, the city provided two of the three leading candidates for the Nevada senate seat open that year. William Sharon, chief Nevada representative of the Bank of California, maintained a legal residence in Nevada although he lived in San Francisco after 1872. Adolph Sutro, the other San Francisco candidate, had left the city for Nevada’s silver mining region in 1860, but his family continued to live in the city until the early 1870s, and his children attended school in the Bay Area while their father sought election to the Senate from Nevada. Sharon won the election but took over both the Palace Hotel and the Bank of California the same year and lived in San Francisco during most of his term. Sutro’s family returned to the city in 1879, although Sutro made another try to defeat Sharon in 1881. The victorious candidate that year, however, was James Fair, a partner in San Francisco’s Nevada Bank. Fair bought a home in San Francisco shortly after his election, but his wife divorced him and received the mansion as part of the settlement. Fair lived in Washington when the Senate was in session and at other times in the Lick House in San Francisco, one of his many investments in city real estate.(12)

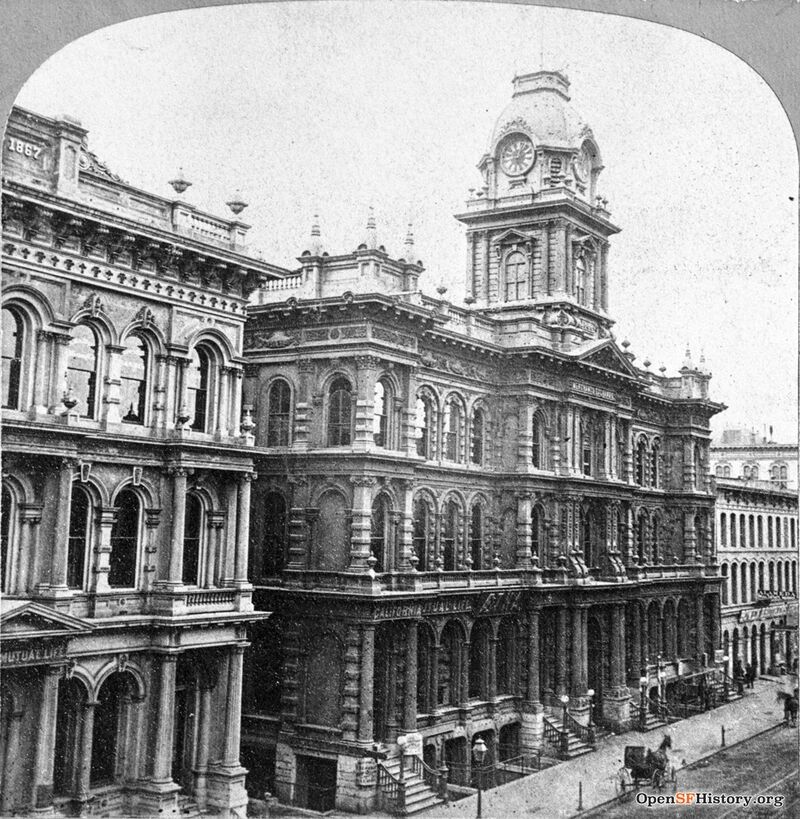

View southwest across California Street to second Merchants Exchange Building, 1866.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp37.01405

San Franciscans saw Nevada as a satellite on the east and took a similar view of Alaska to the far north. In 1870, several San Francisco firms submitted bids for an exclusive franchise to take seal pelts on the tiny Pribilof Islands off the coast of Alaska. Congress had not yet created a territorial government for Alaska, but its potential as a source of furs was well known. John Miller, erstwhile Collector of the Port of San Francisco, prominent Republican, and president of the Alaska Commercial Company, won the contract. Senator Cornelius Cole, a former business partner of Miller’s, and Senator William Stewart of Nevada, a close associate of Louis Sloss (who both preceded and succeeded Miller as company president), provided important assistance in securing the contract. Miller himself went to the U.S. Senate in 1881. The Alaska Commercial Company rapidly extended operations to the mainland fur trade, established a virtual monopoly there, and operated with virtually no restraints. Until 1884, Alaska had no real government. Some insisted, in fact, that the San Franciscans who ran the company and their Washington lobbyist exercised a veto power over political development in Alaska.(13)

The men who dominated the financial and commercial life of San Francisco in the nineteenth century knew their way about the corridors of power. They understood that the economy was political, and they realized that success for their far-reaching business concerns required a firm grasp of politics. No other city in the nation could boast of having three residents sitting simultaneously in the U.S. Senate! City politics was a penny-ante game compared with the stakes for which these men ordinarily played. Further, they knew the limitations on city government imposed by the Consolidation Act of 1856. In an effort to prevent corruption, that document granted few powers to the Board of Supervisors, made appropriating funds difficult, prohibited debts and liabilities, and reduced the mayor to little more than a presiding officer. The intent—and to a large extent the effect—was to reduce city government to administration, with little potential for initiative. John P. Young, in 1912, characterized the result as “dry rot.” In the 1860s, the legislature removed the waterfront, heart of the city's economy, from control by city government and transferred it to a state commission. The most routine city business required approval by the state legislature. Even the widening of Kearny Street, undertaken in 1866, needed prior legislative authorization.(14)

William Ralston and the Politics of Urban Development

The widening of Kearny Street inspired William Ralston to a more grandiose scheme to revise the city's streets. He proposed extending Montgomery Street, an important commercial thoroughfare, straight south across Market, slashing through those blocks (all diagonal to the proposed new street) and providing access to the industrial area developing south of Market. Ralston presented this proposal to the supervisors in late 1866, and, after lengthy hearings, the supervisors accepted the plan by the narrow margin of seven to five. When this brought a mayoral veto, the seven-to-five margin changed to the two-thirds necessary to override. The surveying generated so much controversy that the project ground to a halt. In the meantime, John Middleton won election to the state legislature in order to secure authorization for a massive cut through Rincon Hill. The cut produced a nearly level grade for Second Street from Market to the docks at the foot of First and Townsend, an area where—not coincidentally—Middleton held property interests. Ralston abandoned his Montgomery South plan and embraced a less drastic alternative. He and Asbury Harpending proposed to create a new street that would run parallel to Second and meet Montgomery at Market. New Montgomery Street involved both a new commercial thoroughfare from Market to the docks and the leveling of Rincon Hill. The legislature authorized the scheme after (according to Harpending’s memoirs) payment of $35,000 to Sacramento vote brokers, daily restaurant bills of $400, and intense lobbying in both Sacramento and San Francisco. When the legislature later repealed the authorization. Ralston and Harpending constructed two blocks of the new street using their own land. They then sought to pull the financial and commercial center of the city southward toward their new street by constructing the Grand Hotel, on New Montgomery at Market, and then the Palace Hotel, facing the Grand across New Montgomery.(15)

The Grand Hotel (left) and the Palace Hotel (right) on either side of New Montgomery Street where it goes south from Market, c. 1890s.

Photo: Online Archive of California

Ralston wanted the Palace to be the world’s finest hotel, and he hoped it would revitalize his New Montgomery Street Real Estate Company. But the construction of the Palace further drained his already depleted resources, and he turned in desperation to a scheme to sell water to the city. Ralston, like most San Franciscans, knew that dissatisfaction with the service provided by the Spring Valley Water Company, the city’s source of water, had convinced the Board of Supervisors to buy out that company. Unlike most San Franciscans, Ralston also knew that an engineer had recommended that the city acquire the Calaveras watershed near San Jose as an additional source of water. He and an associate concocted a bold plan. They bought the Calaveras watershed for $100,000, then began to acquire Spring Valley stock. Ralston’s tight financial situation meant that they could not pay cash. Instead, they offered more than the going price for the stock but paid with certificates promising that price plus interest. They soon “owned” more than half the stock in the company (without having had to pay for it) and used their control to sell the Calaveras watershed to the Spring Valley Water Company for more than $1 million—a profit of more than $900,000. Its assets augmented by $1 million, the company was now worth about $10 million. Ralston and his partner then offered to sell the entire company to the city for $15 million—another $5 million profit, enough to bail out Ralston’s other faltering enterprises. The proposal brought a tidal wave of opposition, and the supervisors refused. Undaunted, Ralston looked to the upcoming city elections and began organizing a slate of supervisorial candidates favorable to his scheme. Before election day, however, Ralston’s financial juggling act faltered. Forced to resign the presidency of the Bank of California, he died during his daily swim in the bay. His slate also failed, and the Spring Valley Water Company remained a private corporation until well into the twentieth century.(16)

Excerpted from San Francisco 1865-1932, Chapter 6 “Politics in the Expanding City, 1865-1893”