Western Addition Early 20th Century Life and Work

Historical Essay

by William Issel and Robert Cherny

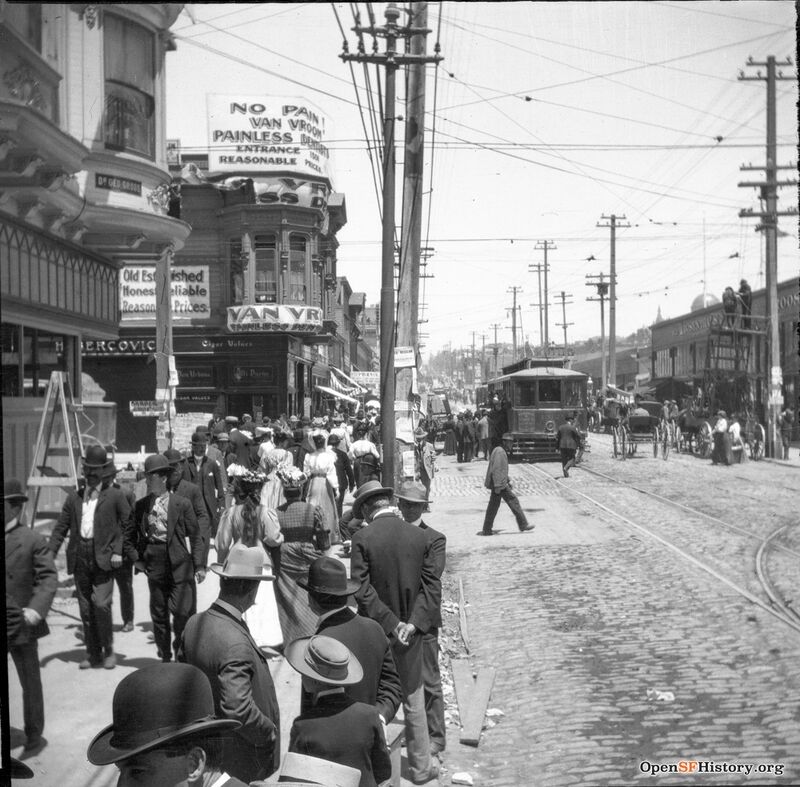

Fillmore Street looking north at intersection with Ellis Street, 1908.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library, courtesy C. R. collection

Although some upper-middle-class businessmen and professionals were to be found throughout the Mission District, these groups appeared in larger proportions elsewhere in the city. Before 1906, and to a great extent before World War II, the Western Addition was home to much of San Francisco’s upper middle class. The Western Addition formally refers to the area opened for residential construction in 1855, west of the survey previously in effect, extending from Larkin Street to Divisadero, north of Market. The destruction in 1906 stopped at Van Ness, leaving the rest of the Western Addition relatively unscathed by earthquake and fire. Before 1906, Van Ness was a street of elaborate mansions, and Polk Street (one block to the east) was an area of small shops and stores. Frank Norris chose Polk Street for the location of the dental office and sleeping room of the title character in his first novel, McTeague. After 1906, Polk and Van Ness both became commercial thoroughfares.

Fillmore and O'Farrell, 1908, during the heyday of Fillmore Street's life as the center of San Francisco retailing.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp14.10601

Fillmore Street, a shopping thoroughfare running north and south through the center of the Western Addition, briefly became a commercial center for the city after 1906, before the downtown stores were rebuilt. As that happened, some of the houses around Fillmore began to be subdivided into apartments, and the Western Addition began to change from an upper-middle-class neighborhood of homeowners. At about the same time. Japantown began to develop along Buchanan between Geary and Pine. Following World War I, a black neighborhood developed nearby, west of Fillmore between Geary and Pine. Before 1906, however, the Western Addition remained largely upper-middle-class and upper-class, home to businessmen and professionals. The houses were similar to those elsewhere in San Francisco in the late nineteenth century—two- and three-story rowhouses, with little or no yard in front. Reflecting the higher income levels and social pretensions of most Western Addition homeowners, many of their houses were both larger and architecturally more elaborate than those of the Mission District. Harriet Lane Levy’s description of the 900 block on O’Farrell could have been repeated time and again for much of the rest of the Western Addition:

The houses on the north side of O’Farrell acquired variation by the swell of a bay window, or the color of a painted surface. All buildings gave out a fine assurance of permanence. . . . The planked street, held together by thirty penny spikes, resisted the iron shoes of the heavy dray horses. Houses, sidewalks, street were of the best wood provided by the most reliable contractors, guaranteed perfect.(22)

In the heart of the Western Addition, about 95 percent of the population lived in families in 1900, and—unlike most of the rest of the city—women outnumbered men. About 30 percent of the people were foreign-born, and three-quarters were of foreign parentage. Here were to be found the largest concentrations of Germans in the city. Here too were significant numbers of Asians, probably half of them in Japantown, the others throughout the area as live-in servants.(23)

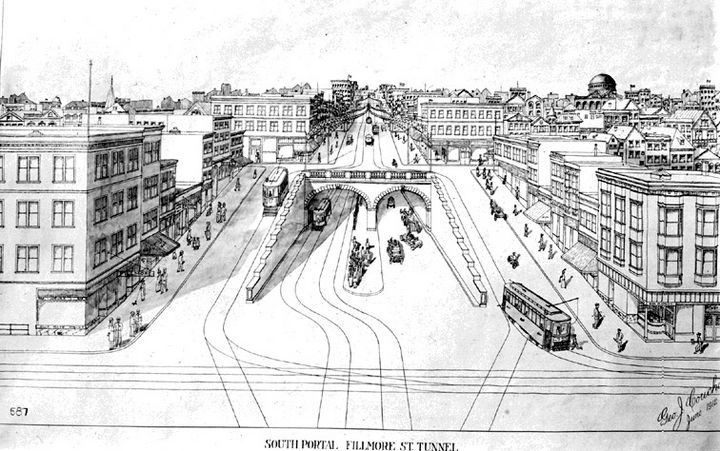

Fillmore Street, c. 1911, when it was the commercial hub of the city. Plans were drawn up in 1912 to tunnel beneath Fillmore Street to the Marina District, but the plan never came to pass. Note the Arches above the street.

Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco, CA

Artist's rendition of a 1912 proposal for a tunnel beneath the Fillmore to the Marina.

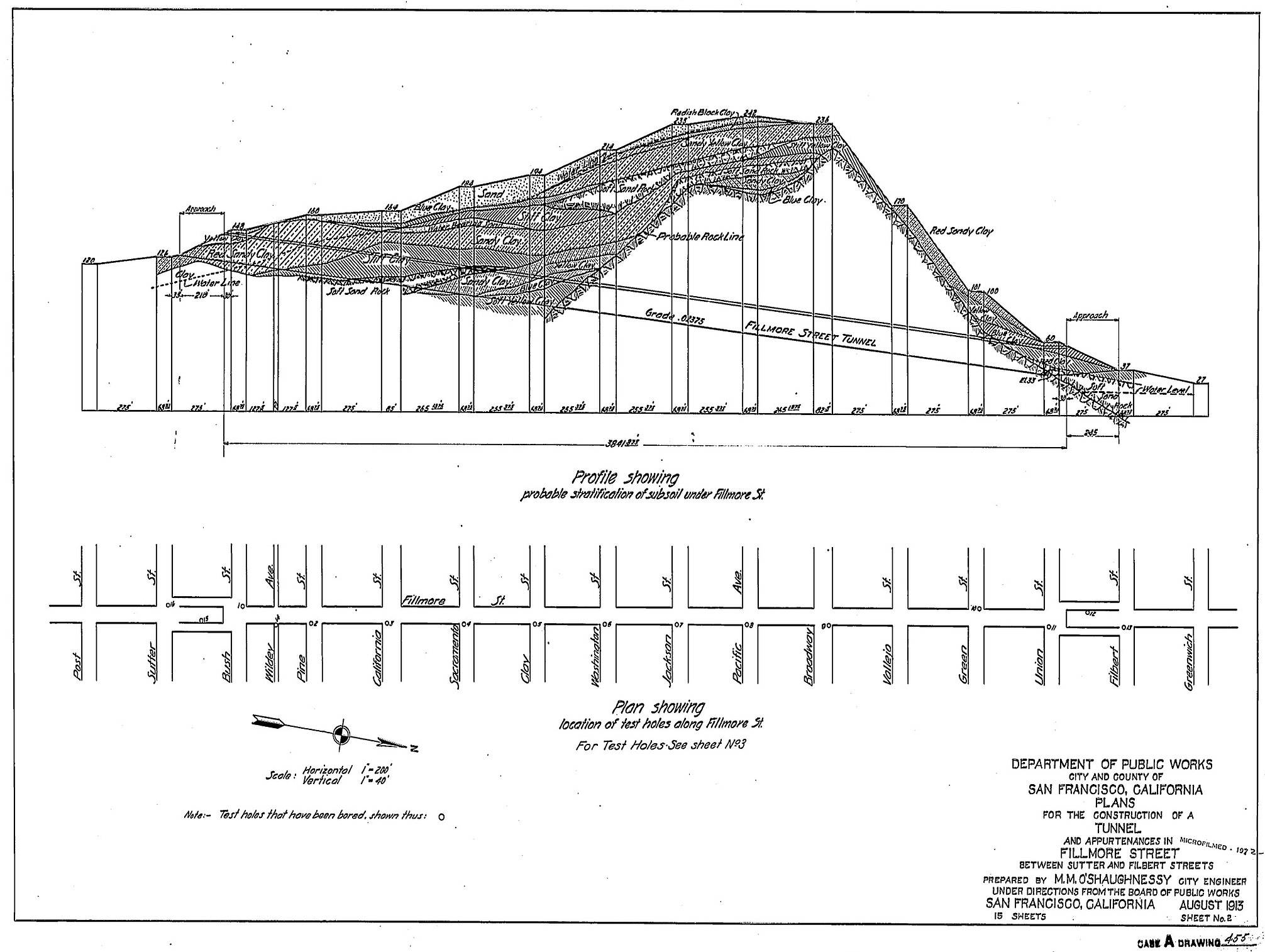

August 1915, Fillmore Street Tunnel plan showing geology and elevation.

Images: courtesy Eric Fischer

The 1700 block on Bush Street had many of these characteristics. There were twelve houses on that block and twelve families, one—and only one— per house. Two families, both headed by widows, each had two boarders or “guests.” Ten families had a live-in servant, and one family had two. Nine families owned their homes, three rented. Families here, as in the Mission and South of Market, were large. Four consisted of three people, two had four or five, and six had six or more. Of the forty-one adults, not including servants, twenty-four had both parents born in Germany and Austria. Eight had one or both parents Irish, six had one or both parents born in England or Scotland, two were of French parentage, and two had both parents born in the United States. Among the twelve servants, four were Irish, two were Chinese, and only one was born in the United States. In only two families, both of them Irish, was the servant of the same ethnic background as the family.(24)

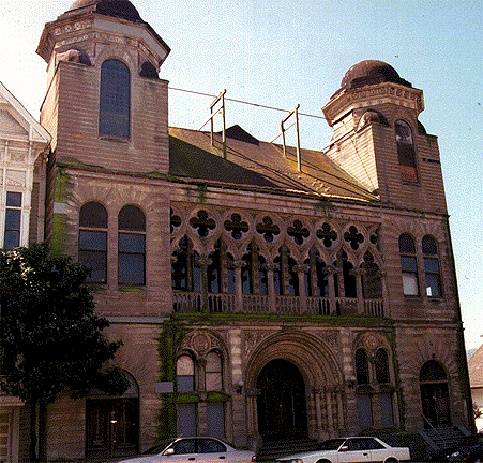

Built in 1895, Temple Ohabai Shalome is now known as Pacific Hall (1881 Bush Street)

Photo: Chris Carlsson, 1998

Many of the residents of the 1700 block on Bush were Jewish, as were many others in the Western Addition at the turn of the century. One block west down Bush was the Bush Street Temple, home of Congregation Ohabai Shalome, one of the most conservative in the city. On the 1700 block of Bush lived Jacob Nieto, rabbi of Congregation Sherith Israel, a more liberal temple. Sherith Israel had been located downtown at Post and Taylor streets from its early days in 1868 to 1905 when a temple was dedicated in the Western Addition at California and Webster streets. Other congregations also established temples in the Western Addition beginning in the 1890s, moving from Downtown or South of Market. The largest temple in San Francisco, Emanu-El, a reform congregation formed by Bavarians, remained downtown on Sutter Street until the 1920s. Other Jewish institutions were also to be found in the Western Addition. Mount Zion Hospital opened on Sutter near Scott in 1898, and in 1913 a new building was completed at Post and Scott. The Jewish Educational Society operated a Hebrew school in the Western Addition beginning in 1908. The Sinai Memorial Chapel (Chevra Kadisha) began in the South of Market area in 1901 but moved into the Western Addition in the next decade. In the late 1930s, 24 percent of the city’s Jewish population lived in the Western Addition, another 32 percent lived directly to the west in the Richmond district, and 16 percent were directly north of the Western Addition in Pacific Heights and the Marina.(25)

The occupations of all residents of the 1700 block on Bush are clearly identifiable. Of the twenty-three adult males, the largest number were merchants: a father-and-son crockery business, a partner in a wholesale notions company, a partner in a clothing company (wholesale, manufacturing, importing), a retail cigar store owner, and a father-and-son cigar-importing business. Others on the block were employed by merchants. Leopold Baer’s son Sam was a clerk at Sachs Brothers, selling gentlemen’s furnishings; his other son Henry, sixteen years old, was a notions clerk, most likely in his father’s business, Gerson and Baer. Arnold Pollak’s son Berthold was a salesman for Zellerbach and Sons, paper merchants; his sixteen-year-old son Irving was a stationery clerk, perhaps for the same firm. Joseph Adelsdorfer’s son Max was a manufacturer’s agent, and Anna Herrold’s son was a clerk for the Harbor Commission. Bella Clapp, boarder with Anna Herrold, was the bookkeeper for a firm of wholesale grocers, and the brother of Rabbi Nieto was a tea salesman. In all, eleven of the streets twenty adult males who were employed were in merchandising. Morning on the block must have seen a parade very like that recalled by Harriet Lane Levy from her childhood a few blocks away:

At nine o'clock every morning the men of O'Farrell Street left their homes for their places of business downtown: dressed in brushed broadcloth and polished high hats, they departed soberly as to a funeral. The door of each house opened and let out the owner who took the steps firmly, and, arriving on the sidewalk, turned slowly eastward toward town. A man had not walked many yards before he was overtaken by a friend coming from the avenue. Together they walked with matched steps down the street. All the men were united by the place and circumstances of their birth. They had come to America from villages in Germany, and they had worked themselves up from small stores in the interior of California to businesses in San Francisco.(26)

In addition to the merchants and clerks on Bush Street, three adult males were at school, two of them brothers, both at dental school. The remaining adult males included a piano teacher, a lawyer, a mining investor, a rabbi, and the French consul: one, seventy-year-old Cornelius Driscoll, listed himself simply as “capitalist.” All were in white-collar occupations. There were also two live-in Chinese cooks. In addition to Bella Clapp, the bookkeeper, twelve other women were employed: Kate Maroney’s daughter and one of her boarders as schoolteachers, one as a live-in governess, and nine as live- in servants.

Streetcar #22 on Fillmore, c. 1910.

Photo: C. R. collection

Looking north at Fillmore and Broadway, late 1914, Panama Pacific International Exposition under construction in background. Passengers disembarked here for the two-block ride down to Green Street by gravity car of the unique Fillmore Hill Counterbalance, built in 1895. This electric line ran from 16th Street along Fillmore to Broadway.

Photo: C. R. collection

The Western Addition after 1906 became more Jewish in the same way the Mission District became more Irish. However, a wide variety of other groups could be found in the Western Addition, just as many groups other than Irish lived in the Mission. Virtually all Protestant denominations had communicants in the Western Addition—Baptist, Disciples of Christ, Congregational, Episcopal (four), Lutheran (one English, one German), Methodist (one English, one Japanese), Presbyterian (five), and Unitarian. There were also five Catholic churches, including St. Mary’s Cathedral. A bit later a significant Russian community developed in the Western Addition, complete with church and school. Lowell High School was on Sutter between Gough and Octavia, Sacred Heart Academy was at Franklin and Ellis, and St. Paul's Lutheran conducted a German school at Eddy and Gough. There were also other public and Catholic primary schools scattered throughout the district. King Solomon’s Masonic Lodge met on Fillmore, as did also the Workmen and Foresters. Other social institutions catering to Western Addition residents were located in the downtown area, among the offices of wholesale and retail merchants.(27)

Notes

22. Delehanty, Walks and Tours, p. 132; Frank Norris, McTeague: A Story of San Francisco, ed. Donald Pizer (New York, 1977), esp. pp. 106, 263-–268; Flamm, Good Life in Hard Times, pp. 72–83 ; Writers’ Program of the Work Projects Administration in Northern California, San Francisco: The Bay and Its Cities (New York, 1940), p. 285; Harriet Lane Levy, 920 O'Farrell Street (Garden City, N.Y., 1947), p. 3. For examples of Western Addition houses from the late nineteenth century that have survived “redevelopment,” see the area around Alamo Square, the 2000, 2100, 2200, or 2800 blocks on Bush Street, the 1800 block on Laguna, the 700 block on Broderick, the 300 block on Scott, the 800 block on Grove, the 700 block on Webster, the 800 block on Fulton, or the 900 block on Ellis. See Waldhorn and Woodbridge, Victoria's Legacy, pp. 97–112.

23. Table 104, “Population, Dwellings, and Families, for Places Having 2,500 Inhabitants or More: 1900,” Twelfth Census of the United States: 1900, vol. 2, pt. 2, p. 640; Table 23, “Population by Sex, General Nativity, and Color, for Places Having 2,500 Inhabitants or More: 1900,” ibid., p. 610; Table 5, ‘‘Composition and Characteristics of the Population for Wards (or Assembly Districts) of Cities of 50,000 or More,” Thirteenth Census of the United States: Abstract of the Census with Supplement for California, p. 616. The relevant assembly districts for 1900 are 37th, 38th, and 40th; for 1910, the same. The 38th and 40th are squarely in the heart of the Western Addition.

24. Only two houses from the nineteenth century survive on the 1700 block of Bush, those at 1710 and 1712, both Italianate-style structures built in 1875. See Olmsted and Watkins, Here Today, p. 254. The information on families comes from 1900 Census Schedules, roll 105.

25. Zarchin, Glimpses of Jewish Life, pp. 59, 61, 70, 72, 114–115, 169, 172; Delehanty, Walks and Tours, p. 304; Flamm, Good Life in Hard Times, pp. 77–78; Irena Narell, Our City: The Jews of San Francisco (San Diego, 1981), pp. 49–50; Massarik, A Report on the Jewish Population, pp. 7–8, 1 1; Rafael, Continuum, pp. 1–9, 34; see also Gustav Adolf Danziger, “The Jew in San Francisco: The Last Half-Century,” Overland Monthly 25 (April 1895):381–410; and K. M. Nesfield, “From a Gentile Standpoint,” ibid., pp. 410–420.

26. 1900 Census Schedules, roll 105, supplemented by Crocker-Langley San Francisco Directory, 1900; Levy, 920 O'Farrell, p. 12. See also Narell, Our City, esp. chs. 7–12.

27. Crocker-Langley San Francisco Directory, 1900.

Excerpted from San Francisco 1865-1932, Chapter 3 “Life and Work”