Mother, Mentor, Maestra: Chicana Artist Yolanda Lopez

Historical Essay

by Alexis Terrazas, editor, El Tecolote; republished with permission, September 2021

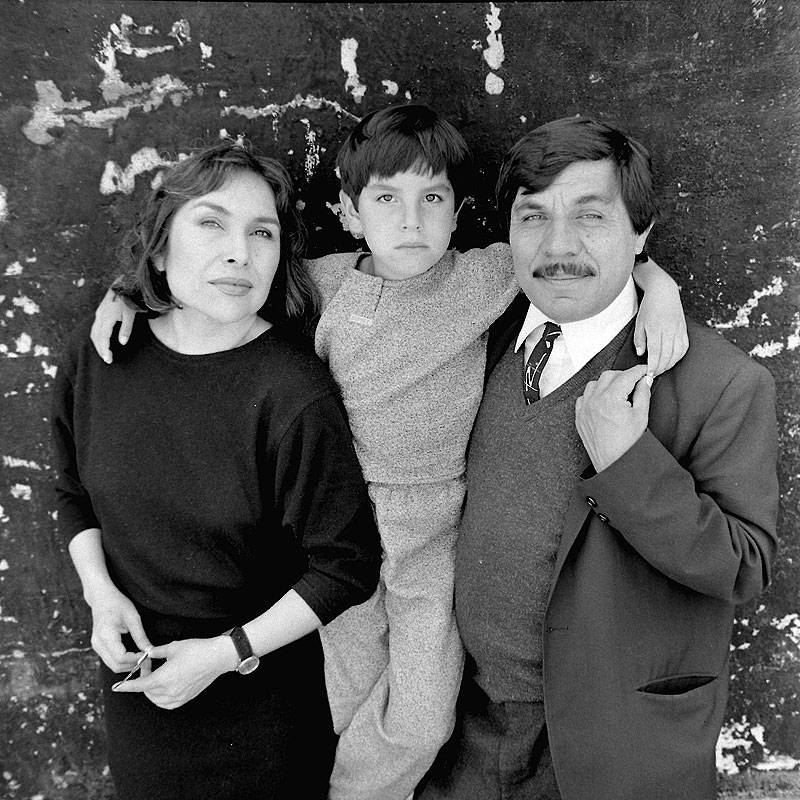

Yolanda Lopez, early 2000s.

Photo: Shane Menez, courtesy El Tecolote

Yolanda M. Lopez, the iconic Chicana artist and activist whose political art paved the way for so many and who called the Mission District home for more than 40 years, died of cancer in her home on the morning of Sept. 3, 2021. She was just shy of 79.

Later that day, dozens of loved ones and friends gathered at the site of her Mission District mural—painted by Jess Sabogal—on Folsom street, to mourn and celebrate her life.

Yolanda Lopez memorialized in this mural on the new building at 17th and Folsom.

Photo: Chris Carlsson; Mural by Jess Sabogal

Rio Yañez addressing friends and supporters of his mother at impromptu memorial beneath the mural, Sept. 3, 2021.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

“It was profound,” said her son Río Yañez of the gathering. “I regret that she wasn’t there. Because it was all of her community and chosen family. Many that were there were there helping her in the last two years of her life.”

The gathering included prints of Lopez created by Sabogal, and a makeshift altar put together by community folk. “It felt like the old Mission that I grew up in,” Río said. “It was the gathering of friends and family that she always dreamed of.”

Born in San Diego on Nov. 1, 1942, Lopez began painting Modigliani-like young women at the age of 12 using the Pelikan watercolors her hairdresser uncle had given her. A shy child, Lopez cruised the library stacks with the same excitement older teenagers cruised down boulevards. By 16, Lopez discovered the beatnik poets and hung a poster of Alfred E. Neuman on the walls of the bedroom she shared with her two younger sisters.

In the early 1960s, when her mother could no longer afford to support her, Lopez moved to the Bay Area. The Chicano movement was beginning to find its voice, and so was Lopez.

“I came out of the San Francisco State Strike, just one of the little munchkins walking the picket line,” Lopez told El Tecolote in 2019. “I was just one little working class Mexican girl taking art classes there.” She worked at the Golden Gate Theatre to support herself through school, occasionally getting her friends in for free.

It was out of the student strike at San Francisco State College, which lasted from 1968-69 and gave birth to the College of Ethnic Studies, where Lopez’s path in political art began.

“I very much saw myself as a revolutionary,” Lopez told El Tecolote in 2019, referring to her political work at the time. “Which meant a whole different way of constructing a society and politics.”

Shortly after the strike, seven Central American youth from the Mission District—who went on to become known as Los Siete de la Raza—were accused of killing SFPD officer Joe Brodnik in May 1969. The arrests galvanized the Mission, and following the lead of Third World Liberation Front spokesperson Roger Alvarado and Los Siete organizer Donna Amador, Lopez joined the fight to free Los Siete.

“I was like nobody in the San Francisco State art department. And when I went with Donna and Roger, I was an artist. I could draw. The biggest benefit that I got from Los Siete was a whole new way of looking at the world,” Lopez said. “I understood what I needed to do as an artist.”

Lopez went on to create the political posters for Los Siete, the first time her work was ever published. “I see it now. And I sort of cringe because it looks so primitive,” Lopez laughed. “But that’s what that was.”

Lopez also designed—with help from the Black Panther Minister of Culture, Emory Douglas—the radical Basta Ya! Newspaper, which served as the voice of Los Siete. And Lopez even served as a sketch artist in the courtroom. Lopez’s archival collection was displayed in Acción Latina’s 2019 exhibit, Remembering Los Siete.

Lopez was part of the Chicano artist wave that gave rise to the future generations of women and Latina artists.

In the late 1970s, Lopez met fellow renowned Chicano artist and cofounder of Galería de la Raza, René Yañez. The two had spent their senior year at the same high school in San Diego together, but met at Galería during one of Lopez’s shows. A few years later, their son Río was born in 1980. And even after splitting up, Lopez and Yañez lived in the same apartment building in the Mission.

Yolanda, son Rio, and Rene Yañez.

Photo: Joe Ramos, courtesy El Tecolote

“I think about her as an artist,” Río said. “Someone who had to stand up and stand for the work she created.”

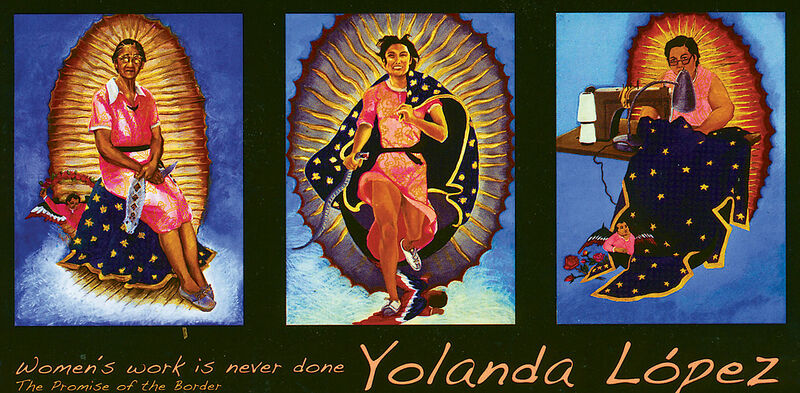

Her most well known art was also her most controversial. And that included her series “Portrait of the Artist as the Virgin of Guadalupe” (1978), which was a direct challenge to the colonial and patriarchal origins of the Guadalupe iconography. The three-image series features the sacrosanct Mexican icon—which is holy even to non-believers—but in place of the virgin, Lopez features the thunderous body of her mother bent over a sewing machine. In the other images, she replaces the virgin with her grandmother, and with herself in running shoes.

Women's Work is Never Done: "Portrait of the Artist as the Virgin of Guadalupe

Image: courtesy El Tecolote

Río remembers backlash: death threats, the smashed windows, the protesting outside exhibits, the men physically trying to intimidate her.

“She really had to stand up for the work that she made,” Río said. “As her son, that was always really inspiring to me.”

An artist in his own right, Río remembers the words of both his parents. “Becoming an artist is taking a vow of poverty.” In his home, that saying rang true. His parents lived paycheck to paycheck.

“They didn’t sugarcoat the realities of being an artist,” he said. “I saw the challenges.”

Yet still, Lopez nurtured the artist in her son.

“My mom always encouraged me to draw. I had a really strong fascination with comic books. She would lie in bed with me and read X-Men comic books. Whatever I was interested in, she was always there to encourage me and cheer me on.”

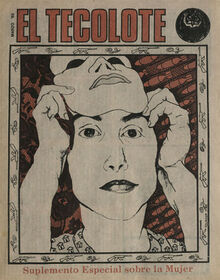

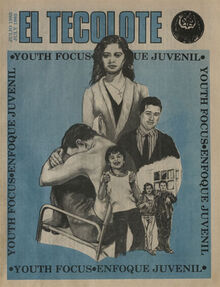

Lopez was also a frequent contributor to El Tecolote newspaper, illustrating various front pages of El Tecolote in the mid 80s.

“She was someone you could count on to contribute,” said Juan Gonzales, the founder of El Tecolote. “She was a very loving person who was willing to give whatever she could. She dedicated her life to giving.”

In a 1988 interview with El Tecolote, Lopez opened up about the challenges of being a working artist.

“The situation for artists is…impossible,” Lopez said at the time. “When young people ask me about being an artist, I tell them not to do it. I have no health plan, no retirement plan, no Social Security (benefits), but I know that’s not going to stop them. Art is beyond logic, we’re driven to do it.”

In the same interview, she spoke openly about being diagnosed with the autoimmune disease, Lupus, motherhood, and her love of life.

“I know death is always lurking about, all I have is the here and now,” Lopez told El Tecolote in 1988. The life lessons, such as the death of her beloved grandmother and that hard work doesn’t guarantee success, freed her from restrictions, like the strings of a balloon being snapped. “They taught me that there’s nothing to lose.”

“I want to feel everything,” she continued. “I want to touch everything, that’s why I’ve forced myself to introduce myself to people and become a mother. I didn’t want to miss out on the experience of having a child. Curiosity drives me. The excitement has always been a big lure, it’s the seductress of life. I feel I’ve lived through a lot of thrilling things, through the beatnik generation, from SNCC (Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee) to hippies and rock music. It’s been like a treat. How can I not love life?”

In late 2013, Río’s parents faced Ellis Act evictions from the apartments they had been living in since 1978. “They had been through so many eras of the community and neighborhood. It was an incredibly difficult time, having to be confronted with the changing face of San Francisco.”

Lopez and Yañez resisted the eviction notices, and became illegal dwellers in their own homes. That was until the Mission Economic Development Agency (MEDA) purchased their building and let them stay.

“If they would have given up, that would have been the end of their foothold in San Francisco. It was something that I really deeply admired about them. They came out of the other side and were able to stay in their home.”

And even now, Río is witnessing the impact his mother had on the community around her.

“One of her most important contributions to the Mission, San Francisco, the Bay Area was her mentorship to so many other artists, over the last three or four decades. She’s played a very quiet yet pivotal role in mentoring these young artists. It’s amazing to see her legacy live on through that influence. How her legacy continues with so many other artists.”

Yolanda Lopez, c. 1970s.

Photo courtesy Rio Yañez