Living Memories, 1931-1960

Historical Essay

by Nancy J. Olmsted

| The Great Depression sunk its teeth deep in the waterfront of San Francisco. There was no steady pay - every morning one had to be selected at the crowded docks to secure a job. Limited work opportunities on the docks and a glut of cheap labor forced many struggling workers to eat at soup kitchens and sleep hunched over a clothesline. It took a bloody strike to eventually secure union hiring halls, a far better system than the previously used daily “shape-ups”. |

The fleet of steam schooners moving along Channel Street served the booming lumberyards during reconstruction after the earthquake. These flush times gradually changed to the lean times more customarily associated with the working class and the waterfront. There was a big (but temporary) blip of prosperity brought on by the need for ships during World War I, but by the ’20s hard times were back.

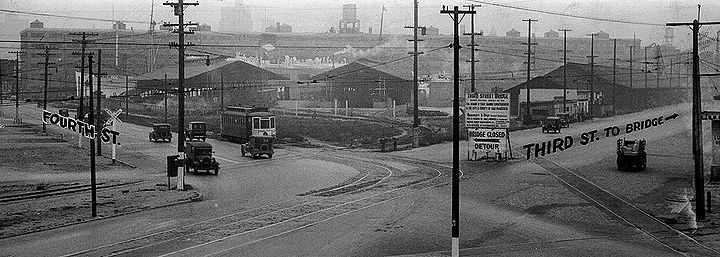

View of United Fruit Company shacks along Mission Creek between 3rd and 4th Streets in 1932.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

After the stock-market crash of ’29, the normally large population of transient, out-of-work men in the south-of-Market area was swelled by waves upon waves of men and boys on the move. One of the boys, Harlan Soeten, arrived in San Francisco at the age of 16 in 1931, hoping to ship out, fascinated by all he had read of life at sea and all he had seen as a young boy hanging around ships at southern California wharves.115

Harlan remembers staying first at the YMCA and then at the Coastline Hotel at Third and Townsend, directly across from the railway depot. “The Coastline was a two-story brick building with a cigar store on the corner and the hotel sort of wrapped around it, with shops downstairs and rooms for rent upstairs. There were a number of longshoremen staying there and railroad men who worked across the street. There were two men who loaded the banana boats for the United Fruit Company, down on Mission Creek. At the Coastline we had a community kitchen and pantry where each man could keep his can of beans and bread. The men sat around playing Pedro, an interesting card game that I never heard of, before or since.

“Then my money ran out and the next thing I remember I was in a real flop house, the Standard Hotel on the corner of Seventh and Harrison. It was a larger, two-story hotel with a sort of entry space guarded by a man who pushed a button to let you in or out. The lobby was a big, dark room with benches and tables. At night they would string up clothesline over the benches and you could rent space for 10 cents a night to sleep, sitting on a bench with your elbows hooked over the rope. Rooms were 25 cents but I wound up in the dormitory, a big downstairs room in back of the washroom. The city rented this space for soup kitchen workers who got free lodging, two meals a day and a package of Bull Durham Tobacco once a week. You bought your package of cigarette papers for a nickel.

“I was picked out of the line by the deputy sheriff who ran the soup kitchen for the city on Clara Alley, near Howard. We served oatmeal in the morning and there would be a line of men, five and six abreast, filling up the alley and extending around to Howard. We’d set up oatmeal, slice bread, and serve coffee and prunes. At 3 o’clock we’d serve hot stew. Those were the two hot meals a day. And the sheriff had a counter to keep track of how many we fed. As I remember, it was 4,000 men at each meal. Of course there were many other soup kitchens—I remember using six different ones.

“I remember walking down to Mission Creek in 1931 and ’32. The United Fruit boats couldn’t turn around in the narrow channel, so a tugboat would tow the big banana boats in by the bow and out by the stern. These were the famous banana boats that unloaded with conveyor belts into box cars at the China Basin Building. They would have shape-ups there in the early morning, if a ship was due on the pier. There would be crowds of longshoremen waiting, hoping for work. The star-gangs were paid by the company and they got the first chance at being hired. If they needed more men the walking boss hired the extra men. He’d say, ‘That’s all,’ and they would drift off looking for work somewhere else. If a banana boat was due in at 10 am and got held up by fog until noon, nobody got paid until noon. There was a lot of standing around and hoping, down on Channel Street and all along the waterfront in the ’30s.”

To have a chance at even one of the 3,000 jobs controlled by Terry Lecrouix, the Dollar Line shipping master, Harlan had to get a shipping card at the “fink hall,” run by the Waterfront Employers Association, and a discharge card from another ship. Only as a work-away could he get that important discharge card. The work-away was paid one dollar a trip, on the theory that he was a stranded sailor trying to get to the next port and willing to work his way there. It was a pool of free labor that kept a lot of men out of work.

The Strike

In 1933, paybacks, graft, bribery and plummeting pay—the average weekly wage earned by star-gang longshoremen dropped to $10.46 produced a situation ripe for union action. That same year the National Recovery Act recognized the right of American workers to organize and bargain collectively. In February 1934 the International Longshoremen Association met in San Francisco and made demands on West Coast shippers. They wanted a minimum of $1 an hour and $1.50 overtime, a six hour day and, most important, the elimination of the shape-up system of company hiring. The strike set for March 7 was moved forward to May 7. All up and down the West Coast other maritime unions joined, and thousands of men didn’t turn up for work.

Police and strikers on Rincon Hill, July 10, 1934.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

San Francisco’s Examiner campaigned to break the strike and on July 5, 1934, thousands of pickets tangled with strikebreakers and police on what was to be remembered as “Bloody Thursday.” Strikers and sightseers were driven up the reaches of Rincon Hill by police throwing tear gas. Royce Brier of the San Francisco Chronicle wrote this eloquent description: “Blood ran in the streets of San Francisco yesterday. In the darkest day this city has known since April 18, 1906, one thousand embattled police held at bay five thousand longshoremen and their sympathizers in a sweeping front, south of Market Street and east of Second. Two were dead, one was dying, 32 others were shot and more than three score sent to hospitals.”116

On July 16 a general strike of sympathy involved every union worker in San Francisco and Alameda counties. Two thousand National Guardsmen patrolled the waterfront, some in small tanks. Reluctantly, the Waterfront Employers Association submitted to federal arbitration and Harry Bridges sent his workers back to work on July 31st. Two months later union hiring halls were a reality.

But the depression remained a fact of life. Until 1941, and our entry into the Second World War, jobs were few and far between on Channel Street and for the workers of the Potrero and Mission Bay.

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/HerbMillsSolidarityAndMorality" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Herb Mills on Solidarity & Morality among the longshoremen of the ILWU.

Video: Chris Carlsson and Steve Stallone

Banana Trade along Mission Creek

This is chapter fifteen of "Vanished Waters: A History of San Francisco's Mission Bay" published by the Mission Creek Conservancy, and republished here with their permission.

NOTES

115. Harlan Soeten interview with Nancy Olmsted, February 13, 1987. Harlan Soeten never got over his fascination with the sea and the ships that sailed. He went on to become curator of San Francisco’s Maritime Museum and is now retired—among other things, he recently built a paddle-wheel steamer by hand.

116. Royce Brier, San Francisco Chronicle, July 6, 1934.