San Francisco’s Second Generation Business Elite

Historical Essay

by William Issel and Robert Cherny

During the first half of the 1920s, one of San Francisco’s most prominent Jewish attorneys, Emanuel Heller, served on the board of the California Pacific Title Insurance company with Phelan. During the 1920s and 1930s, so did the son of Jewish attorney and financier Jesse Lilienthal. Heller put in some thirty years as the attorney for the San Francisco Stock and Bond Exchange. One of the most influential Democratic party activists in California, he was a director of the Union Trust Company, later vice-president of the Wells Fargo Bank and Union Trust Company, president of the Bankers Investment Company, and director of the Market Street Railway and the Spring Valley Water Company. His father-in-law, Isaias W. Hellman (1843-1906) had preceded him as president of Bankers Investment Company, had also been a founder and president of the Farmers and Merchants Bank of Los Angeles, and had moved to San Francisco where he reorganized the Nevada Bank and eventually took over the presidency of the Wells Fargo Nevada National Bank. Lilienthal’s six directorships easily qualified him as a member of San Francisco’s economic leadership group, but his father had also occupied a prestigious position within the city’s business elite before his death in 1919. Besides his presidency of the United Railroads and his position as vice-president of the Anglo-California Trust Company, the elder Lilienthal had served on the boards of no less than eighteen corporations. His cousin, Ernest Reuben Lilienthal, served as president of one of these companies, and by World War I he had made it the largest wholesale liquor firm in the West. Ernest’s son-in-law, Milton Esberg, the son of a pioneer cigar manufacturer, was one of the city’s nationally prominent businessmen, as was his brother Alfred I. Esberg. The elder Jesse Lilienthal’s brother, Philip N., had been one of the founders of the Anglo- California Bank in 1873 and a director of the Union Iron Works.(48) When Philip Lilienthal died in an automobile accident in 1908, he had already become one of California’s leading bankers. His memberships in the Union League and the Bohemian Club, like his directorships in the San Francisco Free Library and the Philharmonic Society, gave him many opportunities for informal social contacts with Protestant business leaders such as William H. Crocker.

William H. Crocker, perhaps the most important single figure in the city’s business elite during the early twentieth century, had begun his banking career in 1883. Rabbi Max Lilienthal had turned to his friends the Seligmans, New York bankers, for help in placing his sons Jesse and Philip in business, but Charles Crocker organized a new firm for his son William. The Crocker-Woolworth Bank was incorporated in September 1886, just a month before William married Ethel W. Sperry, thereby uniting two of California’s wealthiest and most successful business families. When Charles Crocker died in 1888, William organized and became president of the Crocker Estate Company to manage his father’s interests in the Central and Southern Pacific railroads and his real estate investments in San Francisco, Sacramento, and Merced. The following year, he began construction of the Crocker Building at Market and Post streets in the heart of downtown San Francisco. The Crocker Bank moved into the building in 1892, and in mid- 1893 Crocker became bank president when R. C. Woolworth died.(49) Crocker’s reputation rested on his conviction that a natural harmony existed between corporate growth and community progress. John Drum, president of the American Trust Company, testified:

No man ever loved San Francisco more than Will Crocker did, and no other one man ever did so much to develop and better it. No one today knows how many worthy business enterprises were launched or “put on their feet’’ by his financial assistance, but I can tell you the number is legion.(50)

In 1897, Crocker and his brother-in-law, Polish Prince Andre Poniatowski, put California's first hydroelectric plant into operation when they built the Blue Lakes Powerhouse on the Mokelumne River near Jackson. In 1902, they opened a larger plant, to serve the Crocker-Poniatowski gold mines, as well as parts of the cities of Oakland, San Jose, and San Francisco. They organized the Consolidated Light and Power Company, a distribution firm that absorbed smaller companies in San Mateo, Redwood City, and Palo Alto, and they bought the United Gas and Electric Company, thereby developing the means to serve a market that extended from San Bruno to San Jose. After buying out the prince, who returned with his family to Paris, Crocker sold his utility interests in March 1904 to the group that established the Pacific Gas and Electric Company in October 1905. Crocker also provided capital to start the first cement-producing company on the Pacific Coast. Incorporated in 1905 as the Santa Cruz Portland Cement Company, the firm owned one thousand acres of land and a cement plant in Santa Cruz County, and by the mid-1930s it produced ten thousand barrels per day and owned extensive docking facilities in Portland, Oregon, and in Stockton, Long Beach, and Oakland harbors. George T. Cameron, protegé of William H. Crocker at the Crocker Bank and later president of the Chronicle Publishing Company, became president of the Santa Cruz Portland Cement Company in 1908. In 1906 Crocker arranged for a loan to establish the profitable Goldfield Consolidated Mines in Nevada. The mines produced over $100 million, paid high dividends, and replenished the Crocker Bank’s gold deposits during the financial panic of 1907. During the next two years, Crocker began oil investments that led to the organizing of the Universal Oil Company in 1911. With headquarters in the Crocker Building in San Francisco, William Willard Crocker on the board, and Daniel J. Murphy (treasurer of Crocker Bank) as vice-president, the Universal Consolidated owned some 2,000 acres in Kern and Fresno counties, leased another 1,100 acres in Kern and Los Angeles counties, and produced over 1 million barrels per year during the mid-1920s.(51)

With eastern financier Bernard Baruch, William H. Crocker helped finance the Alaska Juneau mine, and he served as treasurer, director, and member of the executive committee of the Bunker Hill and Sullivan Mining and Concentrating Company for forty-six years. This firm mined and smelted silver, lead, and zinc in Kellogg, Idaho, and controlled other mines in Idaho, Washington, and the Yukon. Financial headquarters of the Bunker Hill Company moved to San Francisco shortly after Crocker expanded its capital and came into its management in 1891. Besides his mining activities, Crocker also headed the Crocker-Huffman Land and Water Company that devel¬oped agricultural property near Merced, farmed the land and raised livestock, opened the First National Bank of Merced to provide credit facilities for prospective buyers, and built a municipal water system for the city of Merced. In 1920, Crocker sold the irrigation system (470 miles of canals serving 50,000 acres) to the Merced Irrigation District.(52)

Crocker drew on his friendships with leading East Coast business leaders, such as Bernard Baruch, and his associations with fellow directors of corporations, such as the Equitable Trust Company of New York and the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, when he personally secured millions of dollars worth of loans for the post-earthquake reconstruction of San Francisco in 1906. James Phelan also played a key role in planning and financing the reconstruction process. So did Henry Scott (president of the Mercantile Trust Company, chairman of the board of Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Company, and president of the Burlingame Land and Water Company), John D. McKee (president of the Mercantile National Bank, chairman of the board of the American Trust Company), C. O. G. Miller (president of the Pacific Lighting Corporation and of the Key System Transit Company) and J. B. Levison (president of the Fireman’s Fund and three other insurance companies and director of the Alaska Commercial Company). Crocker, however, “stood out especially,’’ according to William F. Humphrey, president of the Tidewater Oil Company for twenty-five years and long-time head of San Francisco Olympic Club. Years later Humphrey maintained that “it would be impossible to overemphasize the importance of the role [Crocker] played in the drama of San Francisco’s restoration.”

Not only did he rally the business, financial and industrial leaders of the community—as no other man could—to begin the reconstruction before the ruins were cold, but he, more than any other one man, was responsible for obtaining the tremendous amount of money and credit which this stupendous task required.(53)

Crocker’s biographer found a dozen other informants who corroborated Humphrey’s testimony.

The disaster of 1906 provoked what Humphrey described as a “wonderful fraternalism” among the leaders of San Francisco business life. “Old rivalries were forgotten; old jealousies disappeared, and even bitter enmities of long standing were wiped out. Everyone was in the same boat, so we forgot all else and pulled as a team.”(54) This spirit of business brotherhood found expression in the merger of the four largest business organizations into the Chamber of Commerce in 1911 and in both the Portola Festival of 1909 and the Panama Pacific International Exposition of 1915 The Chamber marked the reestablishment of downtown San Francisco as a business center; the latter two events demonstrated the renascence of the entire city.

Both celebrations received their inspiration and their direction from the few dozen business leaders who formed a social and business network around Phelan and Crocker. One of them, Charles C. Moore, became president of the exposition in 1911. He had previously demonstrated his executive abilities by convincing seven European governments to dispatch warships to San Francisco Bay to dramatize the Portola Festival. Head of his own engineering firm, director of the Anglo-California Trust Company and the Anglo and London Paris National Bank, Moore had served a term as president of the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce (1908–1909) and had been chairman of a citizens committee to eradicate bubonic plague in 1908. Although he belonged to the Union League, the Bohemian Club, and the Pacific Union Club. Moore seems not to have attended the luncheon at the Pacific Union Club in the fall of 1909 when William H. Crocker, Henry Scott, and several others revived retailer and real estate developer Reuben B. Hale’s idea for a world's fair in San Francisco. Crocker, first as temporary chairman of the Ways and Means Committee and later as vice-chairman of the Finance Committee and chairman of the board of directors and the Building and Grounds Committee, saw the project through to completion and made an official opening speech on February 20, 1915.(55)

In 1916, Crocker became a member of the Republican Party National Committee, and like his friends Wallace M. Alexander (1869–1939) and Milton Esberg (1875–1939), who served on the national Republican Finance Committee, he played an active role in party politics. Pundits have referred to Crocker, Alexander, Esberg, and Archbishop Edward J. Hanna as “the four musketeers,” or, adding Charles H. Kendrick, president of Schlage Lock Company, as “the big five” in San Francisco public life during the 1920s and 1930s.(56) Alexander, like Crocker a Yale graduate, was born in Maui, the son of missionary parents. President of Alexander and Baldwin, a sugar factoring company, Alexander held vice-presidencies in the California and Hawaiian Sugar Refining Company, Hawaiian Commercial and Sugar Company, Matson Navigation Company, and the Honolulu Consolidated Oil Company and served as director of Columbia Steel, the Savings Union Bank and Trust Company, Home Fire Insurance, Gladding McBean, and Pacific Gas and Electric. Alexander worked to develop trade with Japan by helping to found the Institute for Pacific Relations (1908), traveling to Japan with a San Francisco business commission (1920), and serving as the chairman of the Japanese Relations Commission of California. He supported such Pacific economic development throughout the 1920s as president and member of the board of directors of the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce.(57)

Wallace Alexander entered the sugar-producing, shipping, and refining business after graduating from Yale in 1892. Both his father and his mother’s family (the Cooks, of Castle and Cook) had been pioneers in Hawaiian sugar plantations during the 1870s and 1880s. Milton Esberg went into his father’s wholesale cigar business, Esberg, Bachman, and Company, after graduating from the University of California in 1896. By 1917, he had become vice-president in the General Cigar Company of New York, and during the 1920s and 1930s he served as a director of the Mercantile Trust Company, Southern California Gas Corporation, Pacific Lighting Corporation, the Southern Pacific Golden Gate Ferries, and others. Like Congregationalist Alexander, who was a trustee, Esberg, who was Jewish, had connections with Stanford University as a member of its national board. Esberg joined both Alexander and Crocker as a member of the Bohemian Club, and when former President William H. Taft visited San Francisco in 1919, it was Esberg and Alexander who greeted him.(58)

When Milton Esberg married the daughter of Ernest Lilienthal in 1901, he established family connections with the president of the Pacific Coast’s largest wholesale liquor firm. Esberg’s father-in-law also headed the Sierra Iron Company and the Netherlands Farms Company, served as vice-president of the Union Sugar Company, the Alameda Sugar Company, the Alameda Farms Company, and as director of several real estate companies. Lilienthal had himself joined an established San Francisco German-Jewish pioneer merchant family when he married Hannah Isabelle Sloss in 1876. Her father, Louis Sloss, had been one of the original partners in the Alaska Commercial Company, along with Lewis Gerstle. The Sloss and the Gerstle families maintained very close ties and lived together as a kind of extended family, whether in San Francisco on Van Ness Avenue and Washington Street or in San Rafael in adjacent summer houses.(59)

The connections between the Sloss and the Gerstle families helped bring together Ernest Lilienthal and J. B. Levison. Levison (born in 1862) was marine secretary of the Fireman’s Fund Insurance Company when he married Alice Gerstle in 1896. The couple lived at 1316 Van Ness Avenue between 1898 and 1901, in a house rented to them by Lilienthal. By the time of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), Levison had moved up to the vice-presidency of Fireman’s Fund. The Lilienthal Company had agreed to work as a purchasing agent for the Russian government, and its chartered ships were trying to slip past the Japanese blockade to deliver supplies to Vladivostok. Lilienthal asked Levison to provide the risk insurance on his cargoes, and Levison did so as an independent broker. It was, he later wrote, “a most exciting time for me, to say nothing of the fact that it was my first experience with war risk insurance.” Levison eventually became president of Fireman’s Fund Insurance, vice-president of the Gerstle Company, and director of the Alaska Commercial Company and was in charge of musical entertainment at the 1915 exposition.(60)

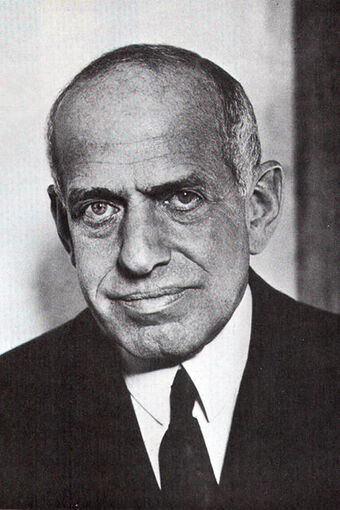

Mortimer Fleishhacker, Sr.

Photo courtesy Mansion Global.

The Levison family lived next door to the Mortimer Fleishhacker family in the Pacific Heights District. Mortimer Fleishhacker became Levison’s brother-in-law when he married Bella Gerstle (Alice’s sister) in 1904. Mortimer and his brother Herbert were the sons of pioneer Sacramento and San Francisco merchant Aaron Fleishhacker (1820–1898). Mortimer was born in 1866 and Herbert in 1872. The Fleishhacker brothers managed their father’s interest in the wholesale paper business before going on to make highly successful investments in electric power between 1896 and 1906, in Oregon as well as California. Herbert became manager of the London, Paris, and American Bank in 1907 and president of the Anglo and London Paris National Bank in 1911. Mortimer Fleishhacker, like his brother a director of more than a dozen diverse corporations, became president of the Anglo-California Trust Company in 1911 and chairman of the board of Anglo and London Paris National Bank in 1932. Mortimer Fleishhacker was a Republican and a University of California regent. Crocker’s Finance Committee for the Panama Pacific International Exposition conducted all of its business through Herbert Fleishhacker’s Anglo and London Paris National Bank.(61)

To San Francisco business leaders, the exposition constituted an architectural advertisement of the city’s renascence after the 1906 catastrophe, as well as a dramatic symbol of its actual role in the California and Pacific Coast economy. “San Francisco,” according to a Chamber of Commerce booklet published for the exposition, “bears the same relation to the Pacific Coast that New York does to the nation.” “Booster” remarks of this kind typified the speeches and publications of Chamber of Commerce representatives, as well as the pronouncements of the city’s mayors, during the thirty years after the earthquake and fire. At the same time, however, the leaders of the San Francisco business community gradually redefined their position in relation to the growing economic importance of Alameda and Contra Costa counties and in response to the rapid advancement of Los Angeles. Between 1900 and 1920, the Los Angeles population grew from 102,000 to 577,000 whereas San Francisco increased from 343,000 to 507,000. The assessed valuation of San Francisco increased from $413 million to $820 million while that of Los Angeles moved from $103 million to $1,276 million. The population growth of Los Angeles and its rising wealth have been called a “reversal of the old, long-established order of things.” To some extent, however, this dramatic process of growth represented evidence of ’he successful policies of San Francisco corporations, for the city’s economic leaders contributed both to the economic growth of Los Angeles and to the expansion of other parts of the state.(62)

After 1906, San Francisco’s manufacturing establishments decreased in number and in value of product compared with pre-earthquake days. But the city could still lay claim to the title of “financial reservoir of the Pacific Coast.” In 1911, San Francisco’s bank clearings ($2,427,075) nearly equaled those of Los Angeles, Portland, Seattle, Tacoma, Oakland, and San Diego combined ($2,531,899). “In San Francisco,” wrote the editor of the Chamber of Commerce Journal, “are made most of the great plans for state development.” The city provided headquarters for corporations whose operations constituted “the industrial ‘vital functions’ of California” The growth of manufacturing in the East Bay, in the words of Contra Costa County entrepreneur H. C. Cutting,

means as much to San Francisco as though it took place within her own city limits, for financially it is all one. We grow together. An immense development is going to lake place here, and San Francisco will always be the main office, the money reservoir where these industries will be financed.”(63)

The investments of John D. Spreckels in San Diego offer a vivid illustration of the ways San Francisco entrepreneurs contributed to economic growth outside the Bay Area. One of the sons of Claus Spreckels, John Spreckels first visited San Diego in 1887 and soon secured a franchise to build a wharf and coal bunkers to supply fuel to the Santa Fe Railroad and to local industry. When the real estate boom of the 1880s ended, Spreckels purchased a controlling interest in the Coronado Beach Company, as well as the water, railroad, and ferry companies associated with the development of Hotel Del Coronado and the island. Within five years, he and his brother Adolph had become the sole owners. During the 1890s and the first decade of the new century, Spreckels developed a water supply system for San Diego; bought the entire south side of downtown Broadway Street; built a series of office, hotel, and theater buildings; purchased the majority of the stock of the city’s two banks and consolidated them; assumed control over two daily newspapers; and reorganized and expanded the city’s streetcar system. Spreckels also bought controlling interest in a tire company, a wallboard factory, and a fertilizer plant, but his most heralded project turned out to be his leadership in building a transcontinental railway line to San Diego. In 1923, not quite four years after the first cars of the San Diego and Arizona Railway pulled into Union Station, Spreckels made a public reply to charges by local critics chagrined by the way the San Francisco businessman had made himself a power in San Diego’s economic life. “I was a young man,” he said,

a young American businessman, looking for opportunities. I was out to find a big opportunity to do big constructive work on a big scale—and in San Diego I thought I foresaw just such a chance. ... It is insinuated that because I undertook those basic developments I have set myself up as a sort of special providence or “savior” of San Diego. Nonsense! I made those larger investments to protect the investments I had already made. I am a businessman, not a Santa Claus—nor a damn fool. Any man who claims to invest millions for the fun of being looked up to as a little local tin god is either a lunatic or a liar. I, gentlemen, am neither. I simply used plain, ordinary business sense.(64)

The economic projects of John Spreckels in San Diego, like the civic work of his brother Adolph in San Francisco, attracted publicity partly because of the glamour and notoriety associated with the family name. Other, less celebrated, businessmen made similar investments, directed equally powerful corporations, and contributed to San Francisco’s economic leadership in analogous ways. Even men who spoke most aggressively about what a 1921 Chamber of Commerce report called “the contest for Pacific Coast Supremacy”(65) between San Francisco and its urban rivals made their decisions about company policy on the basis of what Spreckels called “business sense.” Hence, Colbert Coldwell could speak as president of the Chamber of Commerce in 1923 of the need for San Francisco to “capitalize its natural advantages and step up its voltage for the competitive tournament among world cities,” while opening a Los Angeles office of his real estate firm Coldwell, Cornwall, and Banker in 1924 and an Oakland office in 1925. Three years later, the firm’s Los Angeles profits had grown from $36,802 in 1927 to $90,316 in 1928, while the San Francisco office had registered a decline from $162,275 to $130,234. James Bacigalupi, president of the Bank of Italy, in 1925 urged readers of San Francisco Business to alter their perception of San Francisco’s economic role, “to think in terms of a metropolitan area, rather than a distinct and isolated political subdivision.” Bacigalupi’s definition of metropolitanism matched the practice of both the Bank of Italy, then beginning its statewide expansion through branch banking, and Coldwell, Cornwall, and Banker, then beginning its expansion into southern California and the East Bay. According to Bacigalupi, San Francisco’s metropolitan area stretched “from the sun-scorched Tehachapi Mountains to the snow-capped peak of Mt. Shasta; from the sentinel Sierras to . . . an awakening Orient.”(66) It is tempting to regard such demands for a domestic “Open Door policy" as the rhetorical counterpart to San Francisco business expansion into new territory during the interwar years.(67)

Notes

48. San Francisco Examiner, Jan. 1, 1926; Robert Glass Cleland and Frank B. Putnam, Isaias W. Hellman and the Farmers and Merchants Bank (San Marino, Ca., 1965); Martin A. Meyer, Western Jewry (San Francisco, 1916), p. 191; San Francisco Bulletin, Oct. 12, 1895; Millard, History of the San Francisco Bay Region, pp. 47-48; Who's Who, p. 502; Lillie Bernheimer Lilienthal, In Memoriam Jesse Warren Lilienthal (San Francisco, 1921); F. Gordon O’Neill, Ernest Reuben Lilienthal and His Family (Stanford, 1949), pp. 103-106, 123-139.

49. David Warren Ryder, Great Citizen: A Biography of William H. Crocker (San Francisco, 1962), pp. 47-67; O’Neill, Ernest Reuben Lilienthal, p. 30.

50. Ryder, Great Citizen, p. 71.

51. Ibid., pp. 79-86, 139-144; Walkers, 1935, p. 870; Walkers, 1925, p. 668.

52. Ryder, Great Citizen, pp. 145 — 146.

53. Ibid., pp. 94-95.

54. Ibid., p. 94.

55. Cutler, America Is Good to a Country Boy, p. 106; Ryder, Great Citizen, pp. 120-125.

56. Arthur Caylor, in the News, July 11, 1944, quoted in A Alan and His Friends, p. 133; Charles H. Kendrick, quoted in Memoirs of Charles Kendrick, ed. David Warren Ryder (San Francisco, 1972), p. xiv.

57. Arthur L. Dean, Alexander and Baldwin, Ltd. (Honolulu, 1950), pp. 41—44, 75, 139-140; Who's Who, p. 271.

58. National Cyclopedia of American Biography, vol. E (New York, 1938), pp. 291—292, and vol. 29 (New York, 1941), p. 339; Meyer, Western Jewry, pp. 89 — 90.

59. O’Neill, Ernest Reuben Lilienthal, pp. 31 — 35; J. B. Levison, Memories for My Family (San Francisco, 1933), p. 72.

60. Levison, Memories for Aly Family, pp. 77, 117, 185; Who's Who, p. 28.

61. Levison, Memories for My Family, p. 78; Monroe A. Bloom, A Century of Pioneering: A Brief History of the Crocker-Citizens National Bank (San Francisco, 1970), pp. 5 —6; John P. Young, Journalism in California (San Francisco, 1915), p. 266; Who's Who, pp. 37, 72.

62. San Francisco Chamber of Commerce, San Francisco: The Financial, Commercial, and Industrial Metropolis of the Pacific Coast (San Francisco, 1915), p. 22; Cleland and Putnam, Isaias W. Hellman, p. 86.

63. Frank Morton Todd, “San Francisco City and County,” in California Blue Book or State Roster, 1911 (Sacramento, 1913), pp. 773, 774; Chamber of Commerce Journal (San Francisco) 1 (July 1912): 11, quoted in Mel G. Scott, The San Francisco Bay Area: A Metropolis in Perspective (Berkeley, 1959), pp. 313, 137.

64. H. Austin Adams, The Alan, John D. Spreckels (San Diego, 1924), pp. 293, 294, 171, 182 — 199, 263; San Francisco: Its Builders, Past and Present, 2 vols. (Chicago, 1913), 1:15-17.

65. B. M. Rastall, The San Francisco Program (San Francisco, 1921), Foreword.

66. Colbert Coldwell and James Bacigalupi, quoted in Roger W. Lotchin, “The Darwinian City: The Politics of Urbanization in San Francisco Between the World Wars,” Pacific Historical Review 48 (Aug. 1979):360; Lotchin offers a somewhat different interpretation. On Coldwell, Cornwall, and Banker, see Jo Ann L. Levy, Behind the Western Skyline: Coldwell Banker: The First Seventy-Five Years (Los Angeles, 1981), p. 28; V. P. Brun, Aly Years with Coldwell Banker (Los Angeles, n.d.), pp. I0A—12; on the Bank of Italy, see Marquis James and Bessie Rowland James, Biography of a Bank: The Story of the Bank of America (New York, 1954), chs. 6 — 13.

67. See Cleland and Putnam, Isaias W. Hellman, p. 86.

Excerpted from San Francisco 1865-1932, Chapter 2 “Business and Economic Development”