Interlocking Wealth Clusters Together

Historical Essay

by William Issel and Robert Cherny

Mark Hopkins Residence circa 1895, elevated view northeast from Mason & Pine, Stanford Mansion on right.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org, wnp37.03594

The magnificence of the mansions of the Silver Kings and the Big Four and the massive character of their wealth and power caused the display of luxury by others to pale in comparison. George Hearst, for example, a brilliant self-taught mining geologist, reaped a fortune from the Comstock Lode in the 1860s and, in partnership with James Ben Ali Haggin, controlled a vast mining empire that included silver mining in Utah, gold in South Dakota, copper in Montana, and other interests in Idaho and Mexico. Hearst also owned land throughout California and in Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and Mexico. As a gesture of support for the Democratic party he bought the nearly bankrupt San Francisco Examiner in 1880 and underwrote its deficits for the next decade until his son, William Randolph Hearst made it profitable. From 1886 until his death in 1890, George Hearst represented California in the U.S. Senate.

Hearst lived on Nob Hill, but Peter Donahue lived in a forty-room mansion in the city’s older enclave for the rich on Rincon Hill, not far from the site of his iron foundry in Happy Valley. Donahue's multifaceted entrepreneurial activities made him a sizable fortune. Besides the Street Railroad, the San Francisco Gas Works, the San Jose Railroad, and the San Francisco and North Pacific Railroad, Donahue had also helped organize the Hibernia Bank and the State Investment Insurance Company.(26)

Donahue’s numerous directorships made him a typical member of the top echelon of San Francisco's business community in the eighties. One of the founding members of the Southern Pacific Railroad Company in 1870, he was one of the three directors in addition to the Big Four. Lloyd Tevis was one of the others, and like Donahue, Tevis also had banking interests. Brother-in-law of Hearst's partner James Haggin, president of Wells Fargo Bank Company for many years. Tevis became one of California's largest landholders and had investments in the Risdon Iron Works, the Spring Valley Water Company, the California Street Railroad, San Francisco real estate, and gold and silver mines. Tevis's Taylor Street house, “one of the most capacious and elegant in San Francisco,” was located two blocks from the mansion of George Hearst.(27)

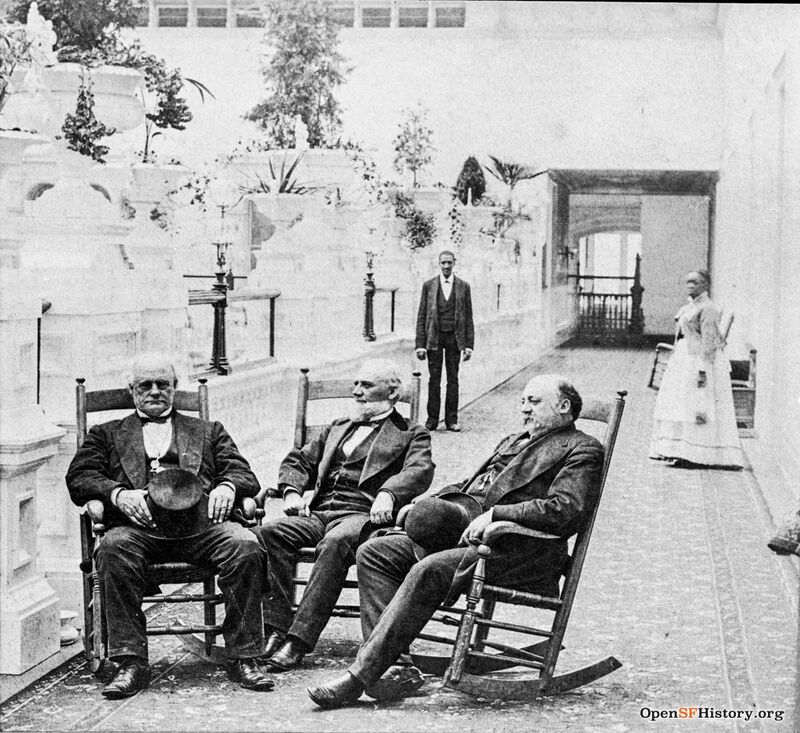

Palace Hotel, 1870s, Lloyd Tevis sits at center with African-American staff in background. In the 1880s, the black workers were dismissed en masse under pressure from white labor unions.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org, wnp37.00867

William Alvord's business address at the Bank of California put him in close proximity to the office of Lloyd Tevis on Montgomery Street. Alvord lived on Harrison Street on Rincon Hill, not far from Peter Donahue’s mansion. Alvord, like Milton Latham, who had also lived on Rincon Hill before moving to New York, combined business enterprise with political service. Alvord started out in the wholesale hardware business, then sold out in order to invest in and supervise the construction of the Risdon Iron Works. He served a term as mayor and found time from his banking business to sit four years as a police commissioner and ten years as a park commissioner.(28)

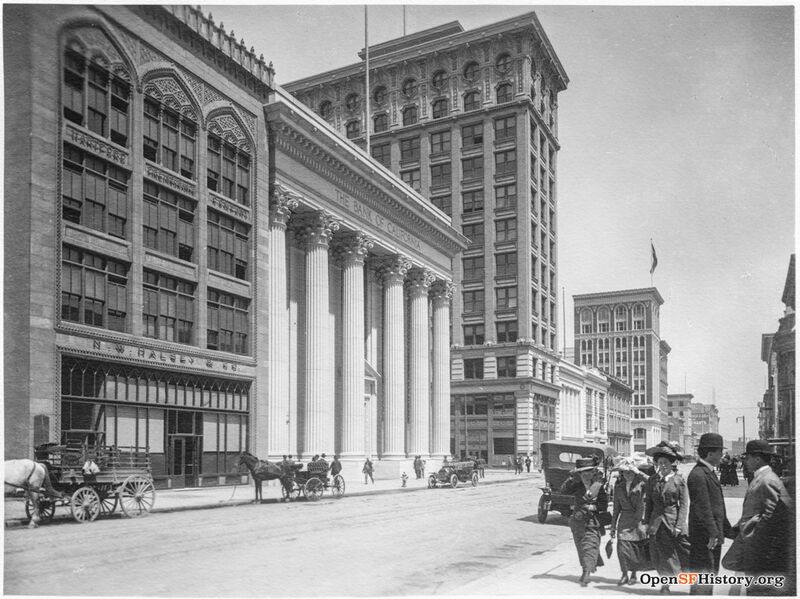

1909 view northeast across California near Liedesdorff to Bank of California and Alaska Commercial Buildings.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org, wnp27.5667

Phelan Building at Market and O'Farrell in 1888.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org, wnp70.0809

Like Lloyd Tevis, James Phelan had faith in the speculative possibilities of San Francisco real estate, and in 1881–1882, he spent half a million dollars to construct the Phelan Building on property he owned at the northwestern corner of Market, Dupont (now Grant), and O’Farrell streets. Phelan came with his parents and two brothers from Queens County, Ireland, in 1821; his father, a graduate of Dublin’s Trinity College, hoped to find relief from Irish rural life in the commerce of New York City. Phelan had already developed successful commercial ventures in New York, Philadelphia, and several southern cities when he opened a wholesale liquor firm with his brother in gold rush San Francisco. The profits from wholesaling allowed him to branch out into wheat, trade, and banking, and he organized the lucrative First National Gold Bank of San Francisco in 1870. He lived near Mission Dolores on a three-and-a-half-acre site and spent summers in Santa Cruz.(29) Phelan, though a benefactor to Catholic activities and city charities, lived a largely private life by the eighties, while his son, James Duval Phelan, directed the banking firm.

Banker Horace Davis, president of the Savings and Loan Society, headed the Chamber of Commerce in 1883–1884, directed the Produce Exchange between 1866 and 1876, and successfully ran for two terms as a member of the House of Representatives. Davis, unlike Phelan, came from Puritan stock, with a father who had been governor as well as senator from Massachusetts. Davis graduated from Harvard before sailing around Cape Horn to California in 1853 and later commanding a ship for the Pacific Mail Steamship Company. He established the successful Golden Gate Flouring Mills in 1860. By the end of the 1880s, he was both the president of the University of California and a trustee of the new Stanford University.(30)

George C. Perkins, who lived in Oakland, regularly commuted to his office at Goodall, Perkins, and Company at 10 Market Street. The firm’s shipping business still thrived during the 1880s, but Perkins occupied himself with the office of governor of California, as well as his presidency of the Merchants’ Exchange, his trusteeships of the Academy of Sciences and the State Mining Bureau, and his directorship in the First National Bank of San Francisco and a half-dozen other corporations.(31) Both Perkins and his partner Charles Goodall started out in life as sailors before the mast. Goodall, a Methodist immigrant from England and a dedicated temperance advocate, served as president of the local YMCA. He also served a term in the state assembly and as a trustee of Stanford University. Goodall evidently preferred the city to the suburbs and lived in a substantial house in the Western Addition.(32)

Notes

26. John S. Hittell, The Commerce and Industries of the Pacific Coast (San Francisco, 1882), pp. 154, 661-662; on the “Big Four” and the “Silver Kings,” see two books by Oscar Lewis, The Big Four: The Story of Huntington, Stanford, Hopkins, and Crocker, and the Building of the Central Pacific (New York, 1938); and Silver Kings: The Lives and Times of Mackay, Fair, Flood, and O'Brien, Lords of the Nevada Comstock Lode (New York, 1947).

27. Albert Shumate, A Visit to Rincon Hill and South Park (San Francisco, 1963); Alonzo Phelps, Contemporary Biography of California's Representative Men, 2 vols. (San Francisco, 1881-1882), 1:29-31.

28. Hittell, Commerce and Industries, p. 138.

29. Builders of a Great City, pp. 281 — 283; Phelps, Contemporary Biography, pp. 355-356.

30. Illustrated Fraternal Directory (San Francisco, 1889), p. 51.

31. Builders of a Great City, pp. 272—273.

32. Illustrated Fraternal Directory, p. 28; Phelps, Contemporary Biography, pp. 200 — 201.

Excerpted from San Francisco 1865-1932, Chapter 2 “Business and Economic Development”