American Business Arrives in Mexican California

Historical Essay

by William Issel and Robert Cherny

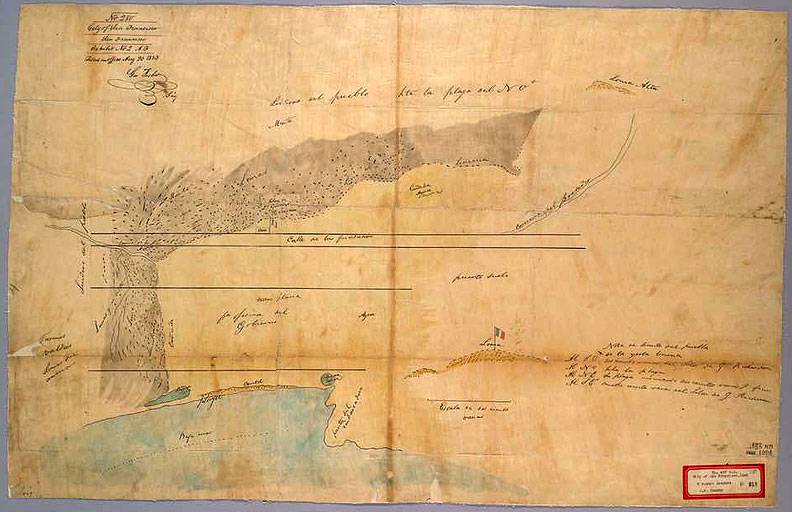

Original William Richardson map of Yerba Buena Cove.

Image: Online History of California

The site upon which San Francisco was to develop struck eighteenth-century representatives of imperial Spain as a likely place from which to protect their claim to northern California. They chose the site because of its location at the entrance to one of the world’s largest harbors. Up to fourteen miles wide and sixty miles long, the bay covered, in all, four hundred square miles. Father Font, a member of the Spanish expedition of 1775, described the bay as “a marvel of nature . . . the harbor of harbors.” Font was convinced that “if it could be settled like Europe there would not be anything more beautiful in all the world.”(3) Hubert Howe Bancroft, writing with the benefit of hindsight in 1888, discounted the adverse effects of forty-three hills on a forty-eight-square-mile site, along with the disagreeable wind, fog. and sandy soil, to say that the San Francisco peninsula seemed “topographically marked for greatness.” The imperatives of imperial policy, not the determining features of topography, placed the Spanish presidio and mission at the entrance to the bay instead of in a more salubrious spot.(4)

Spanish control of the Bay Area, an outgrowth of the imperial policy of “defensive expansion” designed to counter Russian ambitions in the area, lasted until 1822. The San Francisco settlement, never intended to become a city, seemed rudimentary and backward in the eyes of imperial rivals who made periodic visits. English Captain George Vancouver, during his journey around the world, stopped in San Francisco Bay in November of 1792 and found “not an object to indicate the most remote connection with any European. or any other civilized nation.” Russian Lieutenant Nikolai Alexandrovich Khvostov, during an 1806 visit, attributed the Spanish avoidance of “industries” to cultural sources when he described the residents as religious fanatics. But the remarks attributed by Count Nikolai Petrovich Rezanov to Governor Jose Joaquin de Arillaga, that “everybody at present recognizes the possibilities of trade but us, who pay with our own purses for our negligence,” suggest that imperial policy played a crucial role in the maintenance of practices inimical to commercial capitalism. Adelbert Von Chamisso recorded in his diary during the visit of the Rurik in 1816 that the Spanish had “not a single boat in this glorious water basin” and added that one of the Russians had to repair the halyards on the flagpole because no one at the presidio could climb the pole. By then, imperial policy and local custom seem to have reinforced each other to the point where cultural values central to “the business revolution” taking place in the United States, a continent away, would have seemed alien indeed.(5)

Historian Thomas Cochran has used the term business revolution to refer to an interrelated set of changes in the American business system during the first decades of the nineteenth century. Modifying the long-standing emphasis on technology and natural resources as the prime movers of economic growth, Cochran draws on recent research in urban historical geography to suggest that “upward change in the rate of economic growth depends more on a society that under certain conditions fosters improvements in the business structure for better utilizing land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurship than it does on the particular local resources.’’ Stressing the importance of society and culture, Cochran adds that “neither available resources nor technology can by themselves cause change and growth; they require a social system that produces the knowledge and roles necessary to make use of the latent factors.”(6)

Well before California became a state in 1850 and long before San Francisco became chief entrepot for the gold rush, American merchants from New England and the Northeast began to pull Spanish and Mexican California into the orbit of the business system of the youthful United States. Governor Arillaga recognized the potential of “the Bostonians” when he described to Count Rezanov in 1806 “their determined demands” for trade with Spanish ports, which “finally overcame the resistance of the same ministers who, a few years before, would not and did not consent.” “As I have personally witnessed in our waters the enterprise of the citizens of this republic, I am not surprised at their success. They flourish in the pursuit of trade, being fully aware of its possibilities.”(7)

The propensity for the pursuit of trade that so impressed Governor Arillaga was a feature of what might be called the business culture of the northeastern United States. The traditions and the environment of the region had contributed to the making of a culture that placed high premiums on “innovations in craftsmanship and business policy.” Practical, utilitarian, problem-solving techniques took precedence over the guiding hand of inherited customs. A culture favorable to rapid economic development, along with “a well-developed artisan background in the proper industries, freedom for entrepreneurial action, and a high degree of governmental security against interference” contributed to “long-run forces” that were “not dependent on market conditions at any given time.”(8)

The restless seeking after domestic and foreign trade on the part of the merchant capitalists of this culture created demands that enlarged the scope of operations. This led to greater specialization of business practices and to a greater division of labor. Merchants drew on the power of government to promote, rather than to regulate, their activities. Such state assistance, when combined with higher profits, allowed for investment of the large amounts of capital necessary to improve transportation and speed up the transmission of business information. This increased flow of capital stimulated further specialization and greater efficiency in finance: brokers established stock exchanges, dealers in commercial paper emerged, specialized law firms started operations, and investment bankers went into business. Businesses began to operate more economically, decisions could be made on the basis of better information, and the leading commercial centers generated new businesses of all types.(9)

The development of this kind of city-centered business system, already underway when Governor Arillaga made his observations about “the Bostonians” in 1806, was becoming a distinguishing feature of American economic life by the time Mexico secured its independence from Spain in 1821. The California ports at Monterey and San Francisco had grown accustomed to the presence of Yankee and English sea-going merchants, who exchanged finished goods for the lumber, tallow, hides, and pelts provided by the Californians.

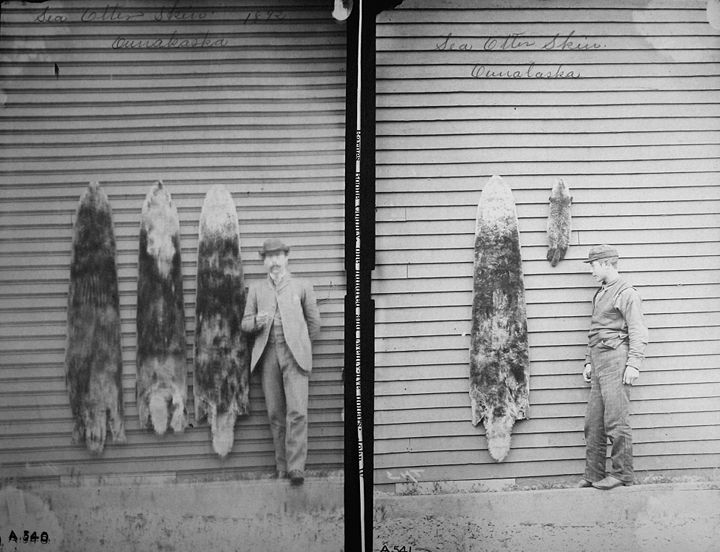

The valuable pelts of sea otters attracted over one hundred ships out of Boston. New York, and Philadelphia during the last thirty years of Spanish control over California. By the beginning of the 1820s. Boston firms such as Bryant. Sturgis, and Company, which had made considerable profit in the sea otter trade, had established regular connections between Boston. California, Hawaii, and China. When the Mexican government authorized trade in hides and tallow at California ports in 1822. Bryant. Sturgis, and Company seized the opportunity to tap a new supply of raw material for the growing shoe and harness industry in New England. Alfred Robinson, who first saw California in 1829. was a commercial agent for Bryant. Sturgis, and Company, as well as other firms: one historian estimates that Robinson alone shipped half a million hides to New England ports.(10)

Sea otter skins, 1892.

Image: Wikimedia commons

Yankees like Robinson, though active up and down the coast in pursuit of cargo, amounted to only a handful of Americans in a society of Californios. Yet their activities in the villages that served as centers for the hide trade made the names of San Diego, Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, Monterey, Santa Cruz, and Yerba Buena well known in Boston merchant houses during the 1830s. “Knowledge follows hard on the wings of commerce,” writes Norman Graebner, “especially when trade is profitable.”(11) During the peak of the hide trade in the mid-1830s, American merchants could sell their manufactured goods for prices that averaged 300 percent above the Boston cost. The lure of such profits attracted competition. In the 1830s, six to eight ships vied for the California market, but by 1842 sixteen ships were on the scene. By 1846, three of the largest companies had deserted the trade. Henry Price’s complaints to his California agent (and later San Francisco merchant leader) William Howard typified Boston’s disillusionment: “I am getting sick,” Price wrote in 1846, “of a business that I once realy [sic] loved, and it is my misfortune to have the brunt of the whole thing heaped upon me by the Stockholders.” The hide trade “was once a profitable business but It now looks like a disasterous [sic] business. ... If we had all of us Invested our money in unimproved Real Estate in this City for the last three or four years It would have been a most profitable business instead of imbarking [sic] in the California business.”(12)

The demise of the hide trade did not imply a decline in the enthusiasm about California ports that the previous decade’s profits had stimulated among American merchants. Yerba Buena, the tiny commercial village established by Englishman William A. Richardson in 1835, sparked American interest even more than some of the other ports by reason of its location at the entrance to San Francisco Bay. Richardson demonstrated the entrepreneurial instincts that distinguished the growing number of American and European settlers in California from the Californios. Whether English like Richardson, native-born like Jacob Leese, West Indian of African background like William A. Leidesdorff, or Irish-American like Jasper O’Farrell, the pioneers of commercial Yerba Buena in the 1830s and 1840s brought a fundamentally different view of the world to the territory they shared with families carrying names like Vallejo, Martinez, De Sola, and Sanchez. The plantation economy, caste society, and culture of gracious hospitality of the Californios stood in marked contrast to the market-oriented practices and the savings-and-investment mentality of the pioneers. Even when the immigrants married into families of local gentry and became adopted citizens of the Mexican republic, as did Richardson, Leese, and Alfred Robinson, they continued to pursue their Anglo-American cultural values of capital accumulation.

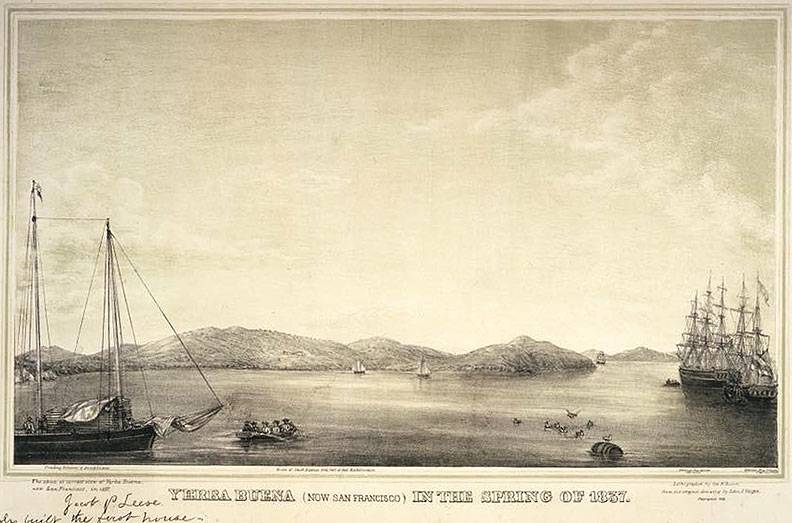

Yerba Buena Cove, spring 1837.

Image, courtesy John Alioto

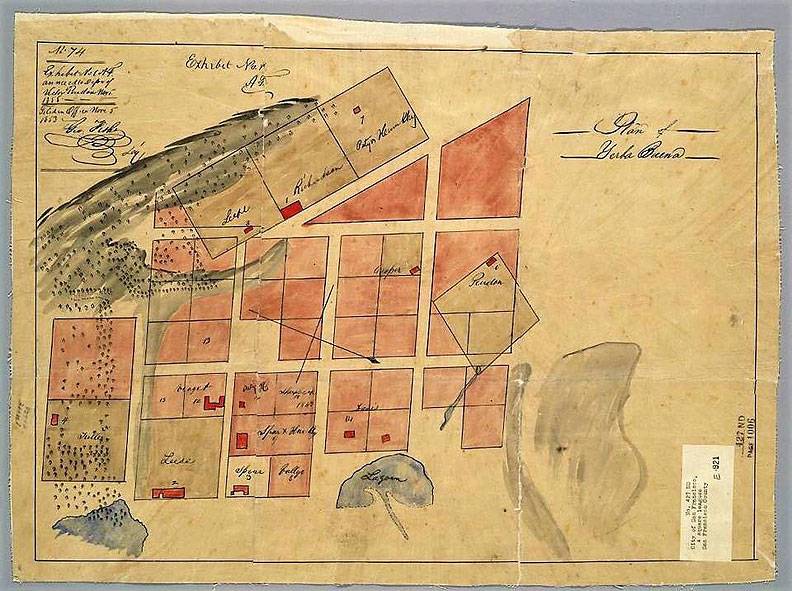

Property map of Yerba Buena cove in the late 1830s, still the pueblo in Mexico's Alta California.

Image: via John Alioto

Although the Mexican government followed an official policy of controlled economic activities, historians have described how its practical day-to-day operations amounted to a virtual laissez-faire paradise for enterprising capitalists. An ayuntamiento (town council) appointed by the provincial governor for Yerba Buena stopped meeting for lack of business. When the alcalde (mayor), who had little to do, rejected Jacob Leese’s application for a land grant beside the cove, Leese obtained it from the governor at Monterey. Richardson, far from being hindered by the Mexican government’s official policy of control over the economy, became captain of the port and maintained a thriving contraband trade in Sausalito across the bay. The informality and personal character of this period allowed such latitude for individual enterprise and is perhaps best symbolized by the town fathers’ practice of keeping the pueblo’s official map and street plan, smudged and barely legible from frequent erasures, behind the bar of a saloon.(13)

Travelers to California (Richard Henry Dana in 1836, John Wilkes in 1841) found nothing impressive about the village of Yerba Buena, but they invariably used superlatives to describe San Francisco Bay. Dana’s popular Two Years Before the Mast (1840) contributed to the large body of information about the Bay Area that was carried east by the growing volume of transportation between California and the Northeast during the late 1830s and 1840s. Wrote Dana:

If California ever becomes a prosperous country, this bay will be the centre of its prosperity. The abundance of wood and water; the extreme fertility of its shores; the excellence of its climate, which is as near to being perfect as any in the world; and its facilities for navigation, affording the best anchoring grounds in the whole western coast of America—all fit it for a place of great importance.(14)

Convinced by advisers that the United States needed the bay for the benefit of American whalers, Andrew Jackson had instructed his minister to Mexico to purchase both the Bay Area and the surrounding territory as early as 1835. International rivalry over the bay began in earnest when the Hudson’s Bay Company opened its branch in Yerba Buena in 1841. South Carolina’s John Calhoun, writing in 1844, pushed for American acquisition of San Francisco Bay and predicted that a city built on its shores would become “the New York of the Pacific Coast, but more supreme, as it would have no such rivals as Boston, Philadelphia, and Baltimore.” Massachusetts Senator Daniel Webster spoke on behalf of New England constituents when he argued in March of 1845 that “the port of San Francisco would be twenty times as valuable to us as all Texas.”(15) The master of the ship Tasso, which had plied the California trade from 1841 to 1843. described the situation as he saw it in 1845:

There is some considerable capital that will be expended in filling up the country round San Francisco with Americans and that I know and eventually you will have another revolution like 1836. With this exception, instead of setting the Mexican ensign it will either be an American one or a new one and American Agents and American capital will be at the bottom of it. You have no idea what feeling there is here with regard to California and Oregon which bye and bye is only used as a blind for the settlement of San Francisco. The egg is already laid not a thousand miles from Yerba Buena and in New York the chickens will be picked.(16)

By June 1846 relations between the United States and Mexico moved from mutual suspicion to war. U.S. troops occupied Yerba Buena and Sonoma, the Bear Flag Revolt having prepared the way for U.S. control over California. President James Polk and his secretary of war had already commissioned the New York Volunteer Regiment and assigned it a twofold mission: to pacify California’s Mexican population and to colonize the area. On July 9, Captain John B. Montgomery officially took possession of Yerba Buena in the name of the United States, and on August 26 he appointed Washington A. Bartlett, one of his officers, as the first American mayor. Alfred Robinson’s Life in California, published the same year, predicted great changes for “the noble, the spacious bay of San Francisco” if the United States would annex the territory. Thousands of ships, new towns beside the bay, river steamers, factories, and sawmills, he argued, would follow the release of creative enterprise that American control would foster. “The whole country would be changed, and instead of ones being deemed wealthy by possessing such extensive tracts as are now held by the farming class, he would be rich with one quarter part. Everything would improve; population would increase; consumption would be greater, and industry would follow.”(17)

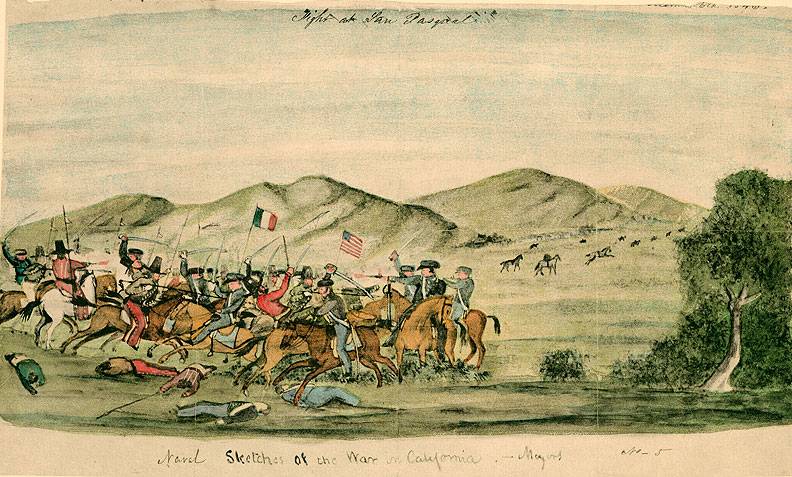

Sketch of Mexican-American war skirmish in California, probably near San Jose.

Photo: Online Archive of California h69.179.1

American settlers followed the flag to California in modest numbers in 1846 and 1847. The majority of Yerba Buena’s population were white males born in the United States, but the city also housed visible minorities of English, Irish, Germans, Scots, Spanish-speaking Californios, Indians, New Zealanders, and South Americans. Two hundred Mormons, unwelcome in many parts of the country, arrived in August 1846 under the leadership of Sam Brannan. By March 1848, the population had increased to just over eight hundred.

The leading merchants and lawyers of Yerba Buena immediately put their stamp on California’s major commercial settlement by changing both the basis for the port’s future internal growth and its relations with other Bay Area towns. Few among the new arrivals, convinced as they were of the settlements inevitable evolution toward Pacific greatness, had patience with the traditional Mexican policies of selling only one plot of land to each resident and of preserving the waterfront for government uses. At first, in late 1846, American authorities issued land grants according to the Mexican laws and refused to allow private development of the waterfront. But after some controversy, Mayor Bartlett authorized a new survey of the pueblo, which extended the borders of the town, established the street pattern of the future city, and became the basis for a flurry of land speculation in late 1847 and early 1848.(18)

Bartlett’s successor, Edwin Bryant, transferred hundreds of acres of waterfront land to the town, thereby preparing the way for individual ownership. In the words of historian William Pickens: “The best tradition of American capitalism, the driving initiative of private ownership could now develop the waterfront.”(19) Jasper O’Farrell’s survey of the city’s territory and the mayor’s actions, which made land into a commodity subject to the market, stood as major portents of change in 1847. So too had Barlett’s order in January 1847 to change the name of Yerba Buena to San Francisco. Predicated on the assumption that the town needed to associate itself with the bay in order to develop a premier role in Pacific trade, the name change blunted the campaign by the town fathers of Benicia to attract shipping to their port at the head of the bay and helped preserve the position already established by Yerba Buena’s commercial leaders.(20)

Notes

4. Hubert Howe Bancroft, History of California, 7 vols. (San Francisco, 1888), 6:6.

.

5. Treutlein, San Francisco Bay, pp. 9, 46; George Vancouver, A Voyage of Discovery to the North Pacific Ocean and Round the World, 6 vols. in 3 (London, 1801), p. 14; for Khvostov’s and Rezanov’s comments, see Richard A. Pierce, ed., Rezanov Reconnoiters California, 1806 (San Francisco, 1972), pp. 25, 53; August C. Mahr, The Visit of the "Rurik" to San Francisco in 1816, Stanford University Publications in History, Economics, and Political Science, vol. 2 (Stanford, 1932), p. 33.

6. Thomas C. Cochran, “The Business Revolution,” American Historical Review 79 (Dec. 1974): 1451

7. Pierce, ed., Rezanov Reconnoiters California, pp. 25, 26.

8. Thomas C. Cochran, Frontiers of Change: Early Industrialism in America (New York, 1981), pp. 7, 8. This and the following paragraph are very much indebted to Cochran’s formulations in his book and in his article cited in note 6 above. The approach here is also influenced by Allan Pred’s work, particularly his Urban Growth and City-Systems in the United States, 1840–1860 (Cambridge, 1980).

9. Cochran, “Business Revolution,” p. 1452.

10. Andrew Rolle, Introduction, in Alfred Robinson, Life in California (Santa Barbara, 1970), p. vii.

11. Norman A. Graebner, Empire on the Pacific: A Study in American Continental Expansion (New York, 1955), p. 51.

12. Henry Price to William D. M. Howard, Jan. 20, 1846, William D. M. Howard Papers, California Historical Society, San Francisco.

13. John Henry Brown, Reminiscences and Incidents of Early Days of San Francisco, 1845–1850 (Oakland, 1949), pp. 24–25, in John W. Reps, Cities of the American West: A History of Frontier Urban Planning (Princeton, 1979), p. 1 10; Jessie Davies Francis, “An Economic and Social History of Mexican California (1822-1846),” Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, 1936, p. 287; see also Douglas Watson, “An Hour’s Walk Through Yerba Buena,” California Historical Society Quarterly 17 (Dec. 1938):291–302; and Geoffrey P. Mawn, “Framework for Destiny: San Francisco, 1847,” California Historical Quarterly 51 (Summer 1972): 165–178.

14. Richard Henry Dana, Two Years Before the Mast (New York, 1936), p. 243.

15. Graebner, Empire on the Pacific, pp. 63, 71–72, 99.

16. S. J. Hastings to Thomas Oliver Larkin, Nov. 9, 1845, in G. P. Hammond, ed.. The Larkin Papers, 10 vols. (Berkeley, 1951–1964), 4:92

17. Robinson, Life in California, p. 157.

18. See Mawn, “Framework for Destiny”; and Bruno Fritzsche, “San Francisco, 1846–1848: The Coming of the Land Speculator,” California Historical Quarterly 51 (Spring 1972): 17–34

19. William H. Pickens, “ ‘A Marvel of Nature; the Harbor of Harbors’: Public Policy and the Development of the San Francisco Bay, 1846–1926,” Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Davis, 1976, pp. 7–8.

20. Roger Lotchin points out that Bartlett’s order merely legalized a change that had occurred three months earlier; see Roger W. Lotchin, San Francisco, 1846–1856: From Hamlet to City (New York, 1974), p. 33. See also Pickens, “A Marvel of Nature,” pp. 14–16, who argues that the rapid development of the San Francisco waterfront played an important role in Benicia’s demise.

Excerpted from San Francisco 1865-1932, Chapter 1 “Commercial Village to Coast Metropolis”