Donaldina Cameron: The Person Behind the Legend

Historical Essay

by Annie Cameron Reller, great great grand niece of Donaldina Cameron, 2021

| Donaldina Cameron, known as Dolly, was a devout Presbyterian whose life work focused on helping Chinese immigrant women escape prostitution in San Francisco in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. There were many missionaries at the time, but Cameron earned notoriety through her brave missions and kind heart. The residents were provided with safety and security, but were also expected to pray daily and confine themselves within the Mission’s Western expectations. |

Cameron and her lifelong assistant and friend Tien Wu.

Photo: courtesy [ https://cameronhouse.org/ Cameron House]

To the brothel owners, she was the White Devil. To the women living in her Mission Home, she was Lo Mo, or Little Mother. To her family, she was Aunt Dolly. Donaldina Cameron made a name for herself at the turn of the century by leading the Occidental Mission Home in San Francisco, providing housing and educational opportunities for Chinese women who were previously mistreated or working in brothels. Cameron worked to save many women from dangerous lives in the sex trade, yet missionary beliefs and forced assimilation still impacted these women’s lives.

In 1882, the US Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, banning Chinese people from immigrating to the US (1). One of the only ways to gain admission to the United States for a Chinese resident was to prove that they were the child of a U.S. citizen, and were thus citizens themselves. This led to many attempts by immigrants to prove, through forged paperwork, that they were the children of other Chinese people already living in America. Many women came to the U.S. only to find that their paper family required them to work in the sex industry, or they were sold in China as human cargo (2). These women lived in horrible conditions, often with forced sex, physical abuse, and little hope of leaving what became known as the Yellow Slave Trade (3).

Cameron came to the Mission Home in April of 1895, when she was 25 years old. Having broken off her recent engagement and dropping out of teacher school, Cameron heard about the Mission House from a family friend. The Mission House was a safe place for Chinese women and girls. They were provided with “food, shelter, and the teachings of the Christian faith.” Over 800 women are recorded as having lived there between 1874 and 1909 (2).

After the second-in-command resigned, superintendent Margaret Culbertson needed help running the home. Cameron joined as a sewing teacher and right-hand manager to Culbertson. Two years later, Culbertson died, leaving Cameron in charge (4). Cameron managed the home, teaching the girls housework and Christian beliefs. Raising money to cover expenses was a constant struggle, and Cameron organized many ways for guests to interact and socialize, having around 20 guests each day (5). She also was the residents’ guardian and had to fight the courts to legally secure their guardianship. Cameron also braved many challenging situations, breaking into brothels to rescue women trapped there (2).

Cameron and residents of Ming Quong.

Photo courtesy personal collection of Ron Cameron.

The Occidental Mission Home was a result of the booming Christian mission industry. In fact, “the number of Presbyterian missionary organizations increased from 100 in 1870 to nearly 11,000 in 1909” (6). Part of this is because throughout the nineteenth century, Missionary work was increasingly accepting of women. “In 1830 females made up 40 percent of the missionary force… the figure rose to slightly more than 60 percent in 1893” (7). Allowing females to be missionaries greatly increased engagement for the churches, so they encouraged women to participate. Society too welcomed this change; missionary work, and social work in general, was an example of leadership that was acceptable for Victorian women. The system itself was based on the idea that there were people who needed saving, and the missionaries were there to save them.

On a personal level, Cameron was remembered for being kind and caring to all people, despite their nationalities. At the same time, she was part of the larger missionary system, in which “the ethnocentric attitude and national and religious absolutism… cannot be denied”(8). Cameron was remembered for how close she was with the home’s residents, and how she made an effort to embrace the women’s culture when she arrived at the Mission Home, incorporating Chinese food and decorations into their daily living (2). However, the very idea that the women needed to be rescued from the vices of the Chinese requires examining. It is true that many women were forced into prostitution, and physically abused. In other cases, the life led by Chinese immigrants was viewed negatively because it was different than the traditional American lifestyle. Additionally, many white people were customers of the Chinatown brothels. Yet prostitution was seen as a Chinese problem rather than a city-wide problem, linking disease and vices to Chinatown rather than the whole of San Francisco.

Cameron was notable due to her daring rescues and the reach of her programs. When, in 1900, there was fear of bubonic plague in Chinatown, police blocked off the roads to quarantine the neighborhood (9). Cameron “made her way from people’s roofs and basement, up and down, and found her way” to a girl she was rescuing (10). Another incident became later known as the Palo Alto Kidnapping; on March 29, 1900, two Chinese men and a police officer arrived at the Mission Home looking for a girl, Kum Quai, who they claimed was a thief. Cameron was used to such antics: it was a tactic used by the brothel owners to reclaim women. Quai was arrested, but Cameron would not let her be alone with the men, so she joined on the train journey to Palo Alto. Quai was to be locked in a cell for the night, and Cameron remained with her. At 2 am, the deputy tried to open the door, but Cameron was suspicious of the early morning entry and barricaded them inside until the officers started breaking down the doors. The men took Quai in a buggy, and Cameron attempted to follow but she was pushed out and tumbled into the road. In a panic, Cameron woke townspeople up to explain what was happening, and frustration spread throughout Palo Alto. Soon a crowd demonstrated in San Jose where the lawyer who planned the event was practicing. “The public uproar led to criminal indictments,” and the men involved were punished (11). This incident led to notoriety for Cameron, and increased support for the Mission House.

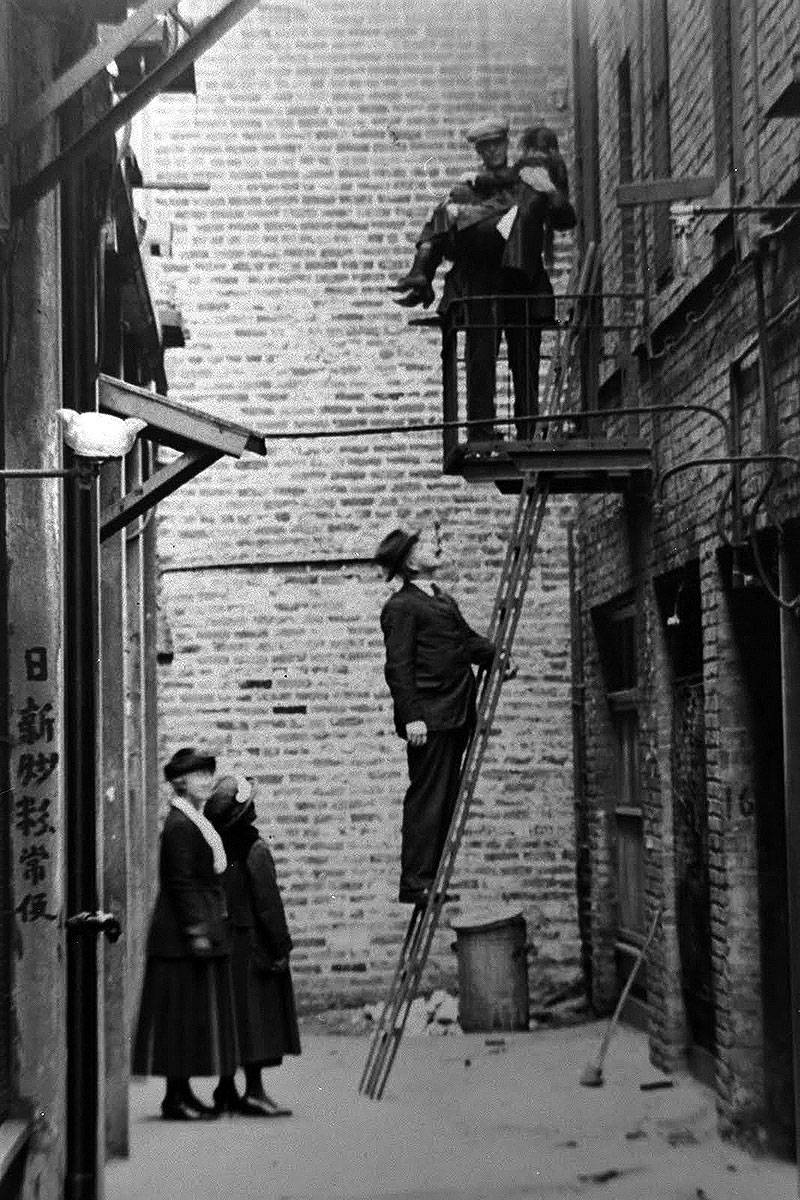

Staged photo of Cameron during Chinatown rescue. Cameron stands at base of ladder during a Chinatown rescue.

Photo: Debunking the "White Rescue Myth", Julia Flynn Siler.

There were also constant threats from brothel owners who were angry Cameron was taking their women. In fact, on Cameron’s first day ever at the Mission House, sticks of dynamite were found around the premises (12). Lorna Logan, who worked with Cameron, credited a strong resolve. "This kind of militancy… she would go to jail with a girl if it was necessary, and she would fight. But at the same time, she would be so loving that she would be so, so concerned about her girl's feelings and fears and family. And those two things don't go together always” (13).

Cameron pointed to her Scottish heritage to explain her bravery. At the same time, she once referred to some of the rescued slaves as “half-frenzied creatures,” employing a white superiority attitude (14). Variously, Cameron strongly opposed racist attitudes towards the Chinese. Brian Donovan, who wrote about how white Americans reacted to new immigrant groups, noted that “Nothing angered Miss Cameron more than the racial discrimination to which Chinese were subjected in housing, employment, and education” (15). For the time, Cameron was progressive and accepting. However, she still forced the residents to comply with her leadership and culture.

There was strict life at the Mission Home with a schedule full of housekeeping, prayer, classes, and entertaining guests. Residents needed staff permission to leave and had limited contact with people outside the home (16). She still forced them to concede to Anglo-American ways: when they married their chosen suitor, they would wear a white gown, rather than the traditional red. White gowns symbolize funerals in Chinese culture (17).

At first, Cameron’s work was deeply ingrained in converting women to the Presbyterian church. However, as time passed she focused more on protecting women and children to give them a better life. When asked if she thought their conversions were real, a question that would offend many missionaries, she replied that it was real for most. Cameron was realistic and did not assume everyone would convert (18).

Despite living in Chinatown for 40 years, Cameron never learned Chinese, and depended deeply on her Chinese aides to complete her work (19). Tien Wu, who arrived at the Mission Home before Cameron, was afraid of Cameron at first and disliked her, until one morning when Cameron’s previous aide passed away. “She came in and just threw herself against her bed and sobbed and sobbed and sobbed… I was very proud to see outwardly [how much she cared].” The next day, Wu began assisting Cameron in her day-to-day work. The pair worked together until Cameron’s death, with Wu living next door to Cameron when she was an elderly woman living in Palo Alto.

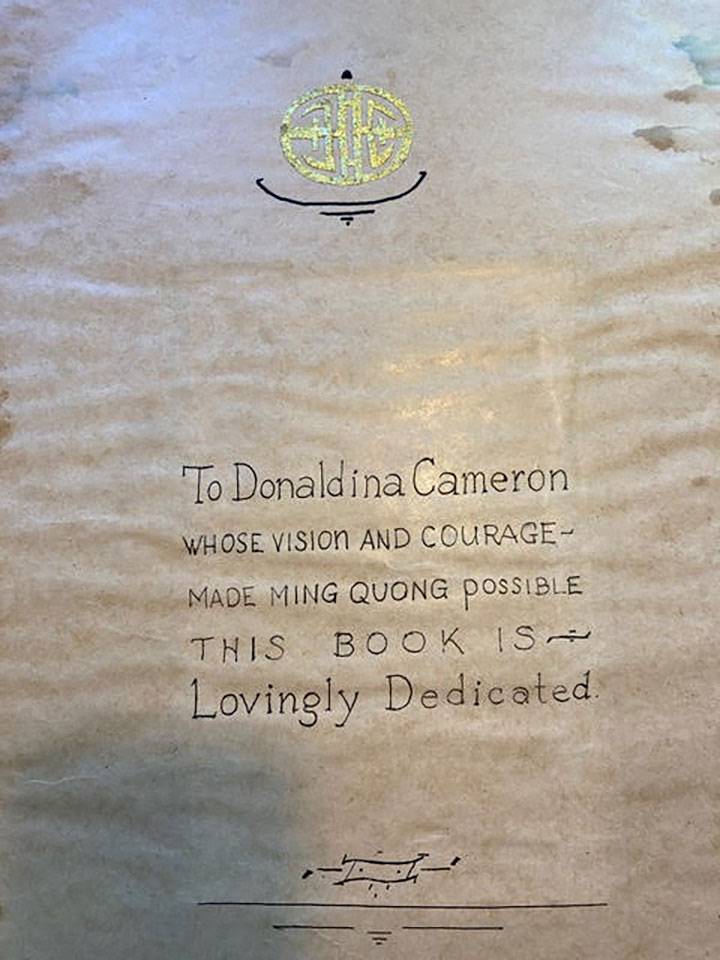

She was remembered for her kindness as well. Ron Cameron, Donaldina’s great nephew, remembers that when visiting the elderly Cameron on her birthday, years after she stopped working, he “would have to get in a line that was about two blocks long of Chinese people who had driven… to wish her a happy birthday… Many of them had their kids with them, and they all gave her cards… after she died we cleaned out her house, there were sacks and sacks of cards like that” (20). He also owns a scrapbook the women at Ming Quong, a children’s home Cameron started, made in honor of Donaldina. “To Donaldina Cameron,” the dedication reads, “Whose vision and courage made Ming Quong possible” (21).

Dedication page of Ming Quong scrapbook. Unknown year of creation.

Image: courtesy personal Collection of Ron Cameron.

By all accounts, Cameron’s kindness seems imperative to her successes. “The thing that… stuck with me,” remembered schoolteacher Dick Wigman, who requested that Cameron speak to his students year after year, “is whenever I have heard Cameron talk about a man, Mr. Lee or Mr. Huang, or Mr. Chen or Mr. Chu, you’d have to be halfway into the story before finding out that it was the butcher, the baker, the candlestick maker. I mean, she had a… very loving and personal relationship… with everybody that entered her life” (12). She was also remembered as proper and orderly, but not cold. Mae Wong, who lived in the home, noted that even in her old age, “she got to be fully dressed, properly dressed. Miss Cameron’s most proper” (22).

Today, Cameron’s legacy of protecting Chinese people in San Francisco’s Chinatown lives on. The Mission Home, renamed the Donaldina Cameron House, still remains in San Francisco’s Chinatown, providing resources for women and their children through the Presbyterian faith (23).

Notes

1. Shah, N. (2001). Public Health and the Mapping of Chinatown, in Contagious Divides: Epidemics and Race in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Berkeley: University of California Press, page 37

2. Siler, J. F. (2019). The White Devil's Daughter. Vintage.

3. Donovan, B. (2007). White Slave Crusades: Race, Gender, and Anti-vice Activism, 1887-1917. Social Forces, 86(1), 375–377. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2007.0092 , page 110

4. Siler, J. F. (2019). The White Devil's Daughter. Vintage, page 97

5. Siler, J. F. (2019). The White Devil's Daughter. Vintage, page 167

6. Donovan, B. White Slave Crusades: Race, Gender, and Anti-Vice Activism, page 117

7. Welter, B. (1978). She Hath Done What She Could: Protestant Women's Missionary Careers in Nineteenth-Century America. American Quarterly, 30(5). https://doi.org/10.2307/2712401, page 623

8. Welter, B. She Hath Done What She Could: Protestant Women’s Missionary Careers in Nineteenth-Century America, page 637

9. Shag, N. Public Health and the Mapping of Chinatown, page 40

10. WU, T. (n.d.). Tien Wu 1969. other. https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/kh509wv0662.

11. Siler, J. F. (2019). The White Devil's Daughter. Vintage, page 131

12. Siler, J. F. (2019). The White Devil's Daughter. Vintage, page 98

13. Logan, L., & Wigman, D. (n.d.). Lorna Logan & Dick Wigman Interview. other. https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/cv159ty4650.

14. Donovan, B. White Slave Crusades: Race, Gender, and Anti-Vice Activism, page 120

15. Donovan, B. White Slave Crusades: Race, Gender, and Anti-Vice Activism, page 123

16. Donovan, B. White Slave Crusades: Race, Gender, and Anti-Vice Activism, page 118

17. Donovan, B. White Slave Crusades: Race, Gender, and Anti-Vice Activism, page 126

18. Siler, J. F. (2019). The White Devil's Daughter. Vintage, page 162

19. Siler, J. F. (2019). The White Devil's Daughter. Vintage, page 152

20. Reller, A. C., & Cameron, R. (2021, May 22). Interview with Ron Cameron. personal.

21. “Ming Quong scrapbook”. Unknown year of creation. Personal Collection of Ron Cameron.

22. Wong, M. (n.d.). Mae Wong Interview. other. https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/gj400hq0839.

23. Donaldina Cameron House. (n.d.). Donaldina Cameron House : A Vision of Hope in Chinatown. Donaldina Cameron House. https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/pr547gc3932.