San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit Commission—The Beginnings

Historical Essay

by Michael C. Healy

Text originally published in BART: The Dramatic History of the Bay Area Rapid Transit System Heyday Books: Berkeley CA, 2016

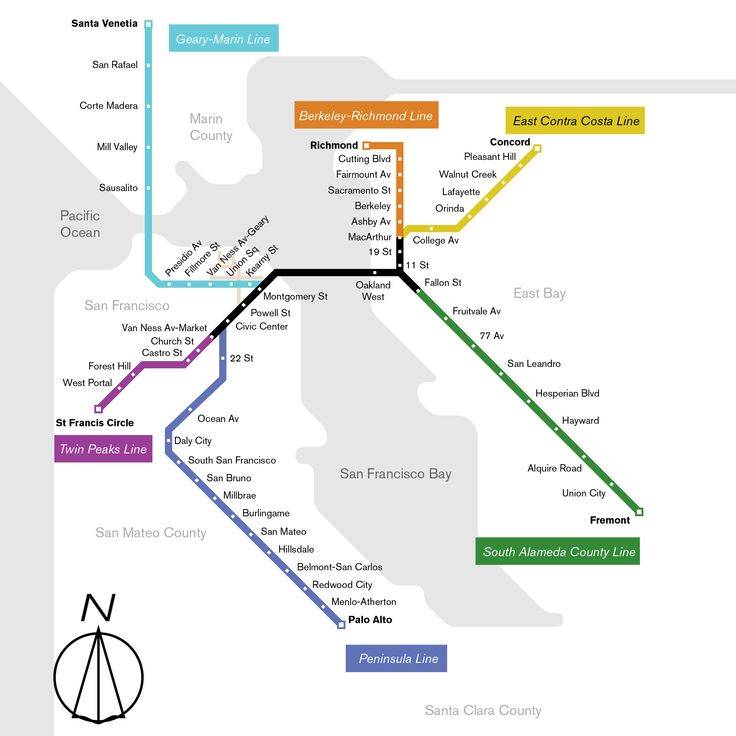

Original BART plan map, c. 1960.

In 1951 the legislature in Sacramento passed an amendment to the 1949 bill… to create the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit Commission. It was signed into law by Governor Earl Warren. The bill appropriated $50,000 for the commission to evaluate the need for a rapid transit district and then report back to the legislature. The new commission’s work was intended to lead to the creation of a master plan for regional transit, although some feared the outcome of the work could differ greatly from what [San Francisco Supervisor and trial lawyer Marvin] Lewis’s unofficial committee was seeking. There were twenty-six members of the newly formed commission, representing the nine Bay Area counties. Most of the members were appointed by the governor and were certainly not beholden to the idea of a regional transit system.

With the official state-created commission now in place, Lewis’s unofficial transit group dissolved. Lewis and other community business leaders, including San Francisco’s venerable Cyril Magnin, Clair W. MacLeod from Piedmont, and John Beckett from Marin County, were among those appointed to serve on the commission. At the very least, these men, all of whom were advocates of a regional transit system, had a voice in the decision-making process, and as it turned out, the commission did end up on the same page as Lewis’s unofficial transit committee.

The primary charge of the commission was to determine how the diversified economics of the region would potentially blend with its geographic features, and how a linear fixed-rail transit system would fit in.

The first thing the commission did in 1951 to help answer such questions was hire De Leuw, Cather & Company, an engineering firm. Its mission was to study the requirements of rail rapid transit from a technical perspective. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, very few regions or individual cities had master plans, as is common today. These plans, if they had existed, would naturally have answered relevant questions about the characteristics of the Bay Area, such as where housing, industry, and commercial development should be located, where recreation areas such as parks and open space should be placed, and how concerns for water availability and utility infrastructure should be addressed.

De Leuw, Cather asked the important questions: Where did the people of the region live? Where did they work? What were their travel patterns? Where was growth expected in the future? Because these questions needed to be answered in a comprehensive way, the consultant’s work was mostly qualitative, in the sense that its findings could only pave the way for a more detailed study of the region. In 1952, De Leuw, Cather & Company submitted its preliminary study to the Rapid Transit Commission, recommending that the commission combine a regional land-use plan with a regional transportation plan, which would ensure that the plans were complementary. The estimated cost for further study and the development of such an ambitious undertaking was $750,000. A hard-fought deal was struck with the state to appropriate $400,000 if the cities of the region would cough up the remaining $350,000. It took a lot of doing, but the various constituent cites within the nine-county region did contribute their share based on population apportionment. The state legislature did not act until 1953 to appropriate its portion of the funds for the project. The goal then became to hire a firm to carry out a comprehensive land-use and transportation study. It was a tall order. Meanwhile, the writing was on the wall for the Key System.

The San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit Commission

In 1953 the work was set to begin on the new BART system. By this time the postwar building boom was in full swing in the region’s suburbs, with new communities springing up and creating what was referred to as urban sprawl. The work had a new sense of urgency, a feeling that time was running out in terms of potential right-of-way availability.

With the $750,000 funding supplied by the state and the various Bay Area cities, the transit commission advertised for consultant bids. Four proposals were submitted. On November 12, 1953, the transit commission awarded a contract to the New York–based engineering consortium Parsons, Brinckerhoff, Hall & MacDonald (PBHM). The firm’s mission was to do a comprehensive study of the nine-county Bay Area from the standpoint of land use and fixed-rail rapid transit. The commission laid out four key questions: (1) Is a rapid transit system needed for the Bay Area? (2) If it is, what areas should it serve and what routes should it take? (3) What type of rapid transit should it be? (4) What will it cost, and will the cost be justified? One of the first tasks was to determine the current travel patterns in as definitive a way as possible. For this the joint venture conducted an origin-destination survey to quantify both commute and non-commute journeys taken each weekday, collecting information on destinations, lengths of trips, and key corridors used.

Two years later, on January 5, 1956, PBHM submitted its findings to the Bay Area Rapid Transit Commission. The report, based on a detailed study of the burgeoning Bay Area community, concluded that there was a pressing need for a balanced approach to meeting the region’s transportation needs, both short-term and long-term. Moreover, the report recommended that a high-speed, grade-separated regional rapid transit system was critical as a complementary component of a highway network, stating also that it was economically justified. It was estimated in 1953 dollars that a rapid transit system serving all nine counties would cost somewhere in the neighborhood of $1.5 billion. It was also recommended that such a system should be built in three stages. The first stage would include an underwater tube between Oakland and San Francisco.

The first phase as outlined by the consultant’s report included six counties. It called for building a line from San Francisco north to San Rafael in Marin County; south through San Mateo County to Palo Alto and on to Los Altos in Santa Clara County; and east to Concord in Contra Costa County, with Oakland serving as the East Bay hub. The vital link would be the tube built under bay waters. In 1953 dollars the estimated cost for an optimal first phase was $750 million. It would require a debt service of somewhere between $33 and $38 mil lion a year for thirty years.

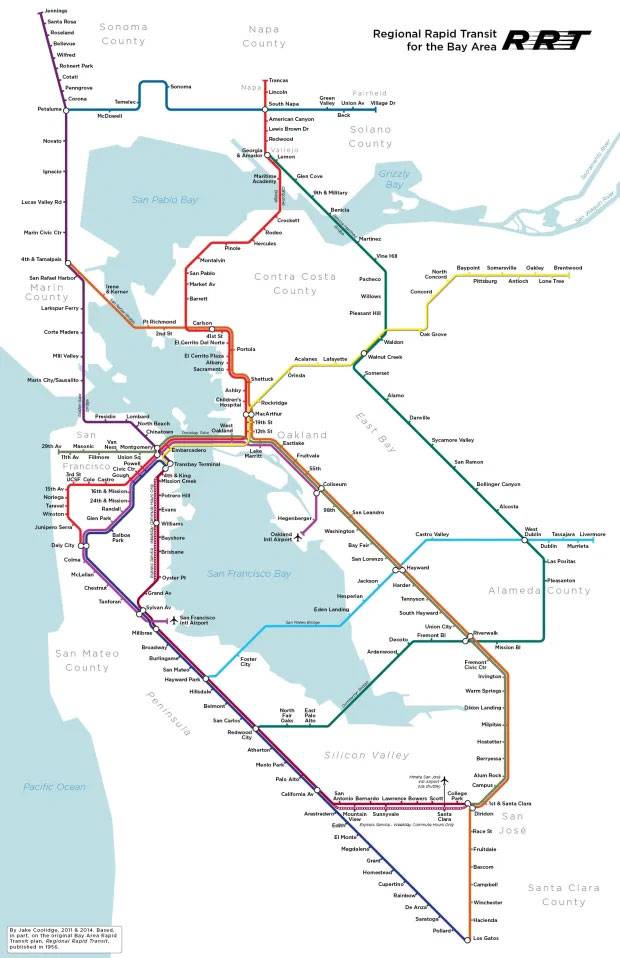

Regional Transit map based on original BART plans from 1958.

Map: Jake Coolidge

The financial plan report had been done by the Stanford Research Institute, whose reputation automatically lent credibility to the numbers. Federal funds were not available for such capital investment in those days, nor was the state providing capital funding. It was clear that future funding would have to come from Bay Area taxpayers. Thus the big question was the feasibility of local taxpayer support. When it came to taxing themselves, Bay Area residents historically tended to pull in their horns. As the report commented in its summary,

Without rapid transit the region will ultimately pay many times its cost in additional hours of travel time, (lost productivity) in additional cost of trucking goods over highways congested by automobiles…, and in the premium costs of urban freeways and parking garages. We do not doubt that the Bay Area citizens can afford rapid transit; we question seriously whether they can afford not to have it. If the Bay Area is to be preserved as a fine place to live and work, a regional rapid transit system is essential to prevent total dependence on automobiles and freeways.

It should be noted that the engineering consultant’s report recognized that plans were already under way for constructing a regional highway system.

The second phase of the recommended plan would construct the line from Fremont south to San Jose and circle back up to meet the line coming south from San Francisco to Palo Alto. Extensions to Antioch and Livermore in the East Bay and from San Rafael north to Novato were also identified as part of the second phase.

The State Interim Committee Holds Hearings

The Bay Area Rapid Transit Commission submitted its final report to the state legislature on January 5, 1956. This prompted the appointment of a State Senate Interim Committee on San Francisco Bay Area Metropolitan Rapid Transit Problems. The interim committee then held public hearings in San Francisco to test the waters, so to speak, and to get a sense of the desirability and feasibility of regional rail transit. This may also have been a way for politicians to determine just how far out they wanted to stick their collective neck in making future decisions on the matter. As it turned out, the waters seemed pretty tepid. No significant opposition to the concept being touted by the PBHM report seemed to exist. One barometer was how the press heralded the report’s recommendations: reporters mostly quoted local officials and prominent citizens who greeted the report with unqualified enthusiasm. Also, the results of a Bay Area survey conducted by the Stanford Research Institute showed 80 percent approval for rapid transit by respondents.

The interim committee, chaired by Senator John F. McCarthy of San Rafael, then published its own report, “Mass Rapid Transit,” supporting the Bay Area Rapid Transit Commission’s work and endorsing the PBHM recommendations. One later change was that, at the county’s request, Santa Clara County was dropped from the proposed bill to establish the Bay Area Rapid Transit District. The bill, jointly sponsored by Senator McCarthy and the interim committee’s vice chairman, Senator Arthur H. Breed Jr. of Oakland, went through several revisions. One involved how district directors would be selected, and another very key provision enabled the District to negotiate for unionization of its eventual employees, rather than making them come under civil service. This critical move was recommended by Clair W. MacLeod of Piedmont, who was a member of the Rapid Transit Com mission. He argued that without the change, the proposed system was unlikely to get support from organized labor.

When it came to figuring out how to financially support this new district once it was created, that particular section of the bill caused a great deal of consternation, and the plan went through several more iterations.

“Everyone seems to be for rapid transit,” MacLeod said, “but they run out the back door when you start talking about who’s going to pay for it.” The outcome was that the District would have very limited taxing powers.

On September 8, 1957, a banner headline in the Oakland Tribune read: RAPID TRANSIT AGENCY GETS OFFICIAL STATUS WEDNESDAY. A three-column story, in advance of the bill being signed into law, set out what the next steps would be in establishing this brand-new agency. The story’s byline named a young urban-affairs writer, Bill Stokes, who was to become a very prominent player in BART’s history.

On June 4, 1957, the California State Legislature actually approved the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District (BARTD) Act, which created a special district made up of five core counties: Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, San Francisco, and San Mateo. The enabling legislation under the California Public Utilities Act recognized that some initial administrative funding would be necessary for the fledgling district. Part of the act gave the new entity the ability to levy a five-cent administrative tax on each $100 of assessed valuation of all tax-roll properties in the member counties, which was considered not much more than a stipend. This approach had been hammered out between Senator McCarthy and members of the Rapid Transit Commission.

On September 11, 1957, Governor Goodwin J. Knight signed the rapid transit bill into law. December 31, 1957, saw the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit Commission fade into the sunset and the brand-spanking-new Rapid Transit District come to the forefront. Its charge: “Build and operate a regional rapid transit system.” But even though the idea had reached this stage, its full execution was still no more than a gleam in the eyes of its longtime supporters. Although it had been created by the state, the new rapid transit district was in many ways born a political orphan, on the street and on its own. A multitude of hurdles and a lot of uncertainty lay ahead, but that first big step in the journey had been taken. Marvin Lewis must have been elated that his early efforts had finally gained traction.

Next Document

Originally published in BART: The Dramatic History of the Bay Area Rapid Transit System Heyday Books: Berkeley CA, 2016