More Than Just Baseball—OctoberTogether

Historical Essay

by Adriana Camarena

Originally published on unsettlers.org, October 28, 2014

Dedicated to Bay Area families victims of police brutality and their supporters

Organizers, activists, and artists at Giants ballpark during 2014 playoffs.

Photo: Adriana Camarena

I. October Spirit

“October Together” is the slogan for the Giants during the 2014 playoffs. Today they play to win their third World Series in five years. The Giants will be playing the Royals in Kansas City for the title. Many of the fans back home will watch together at the Civic Center mega-screen. We Giants fans are at the edge of our seats, because once again, this team of misfits and wild card underdogs stepped up to the plate and outperformed our expectations.

“October together” is also the feeling that I’ve been carrying since the start of the month, when I began working on altars for Day of the Dead, a Mexican celebration of ancestry and deceased loved ones. In late October, the veil between the worlds of the living and the dead symbolically thins, and we can choose to be together again, in grief, joy, mischief, and memory…

I am also at my most homesick in October. I arrived to San Francisco in late October of 2006 driving from Mexico City […]. A week into my arrival, a few Burner friends insisted that I attend Día de Muertos in the Mission. Oddly, we only walked to Mission Dolores from the Castro. I don’t know why we didn’t walk further into the heart of the festivities, but here is where I tethered my memory of arrival. In a niche of the old Mission Dolores, I placed a dead migrating Monarch butterfly. This butterfly had struck and then stuck to my car roof in passing through Michoacan. She was my sacrifice, and so I carried her north to complete her generational journey. A piece of my past was also laid to rest at the Mission Dolores. Two years later, I would settle in the Mission with a lifelong radical San Franciscan who loved the Giants, and had raised a kid in this Latino working class community, where loyalty is a lifestyle.

Photo from “Mission Photo Essay: Still Life After Dark”

Photo: Adriana Camarena

The offering of the migrating butterfly at Mission Dolores now feels symbolic. Living in the Mission, I developed an obsession for comprehending the dolores (the sorrows) that have plagued the people of this conquered valley for a near 240 years to date. I am obsessed with the stories of resistance of the underdogs of society who struggle and sometimes win in the face of fierce adversity, which is how I came to find myself building altars for victims of police brutality this early October.

II. Twilight

On October 3rd, Elvira Nieto and I began painting the walls of our SOMArts altar titled The Twilight of Alex Nieto, in honor of her son, Alex Nieto. Alex Nieto was killed at twilight on Bernal Hill by four still unnamed police officers on March 21st, 2014 at approximately 7:18 p.m. Alex was eating a meal, dressed for his upcoming night shift as a security guard with a licensed holstered taser. Eyewitnesses described him as non-threatening, “just a guy eating a burrito,” watching the sunset over Twin Peaks. Despite the fact that Alex was not doing anything threatening, a dogwalker didn’t like the sight of this young working class man on his path and called 911 to describe a tall Latino male wearing a red jacket and a “gun” at his hip. He added that Alex was eating sunflower seeds or chips. Despite no mention of a threat, police officers rushed to Bernal Hill Park to hunt for Alex.

Alex’s autopsy report shows 15 entrance bullet wounds. Four wounds in an upward trajectory to his wrist, arm, and right lower leg appear to be the initial shots that took him down. The wounds on his wrists seem to indicate that he was raising his hands or taking cover when bullets impacted him. In an impossible story to believe, Chief Greg Suhr stated in a Town Hall meeting that Alex —a young man who had just completed his credits towards a career in administration of justice, and who interned at the probation department— tracked approaching officers with his taser. Chief Suhr admitted that the first shots fired took Alex down to the ground, but in a continued impossible version of events, Chief Suhr explained that Alex —wounded and on the ground— again tracked officers with his taser prompting a volley of shots. The other eleven bullet wounds to Alex’s body were caused by downward trajectory shots to his head, face, chest, and back, indicating that Alex was repeatedly struck by bullets fired by officers from a vantage point, who were evidently intent on killing him, even though he was in a defenseless position.

Refugio & Elvira Nieto sitting in “The Twilight of Alex Nieto” altar at SOMARTS 11/2/14. Collaboratos: Elvira Nieto, Refugio Nieto, Adriana Camarena, Paz de la Calzada, Ivonne Iriondo, and Maria Villalta.

Photo: Adriana Camarena

Over the following first week of October, other collaborators —artist Paz de la Calzada, filmmaker Ivonne Iriondo, Refugio Nieto (father of Alex) and Maria Villalta (friend of Alex and justice cause supporter)— detailed the altar. Our altar references the Nieto Family living room. Here guests are entertained, but here too Alex would watch and translate favorite shows like CSI and Law & Order to his parents, or watch Giants and 49ers games with family or friends. In this room, Alex also slept and dressed, because the living room was also his bedroom.

For our altar, Elvira brought items of Alex’s clothing. She arranged his multicolored baseball caps —all proudly bearing the classic Giants SF lettering—on the same vertical rack that used to hang on his bedroom side of the room. With a mother’s touch, she placed his security guard uniform and vest on a hanger, next to a shiny black Giants shirt with an orange trim. She touched his framed City College certificate in Administration of Justice several times to straighten it just so. The TV remained on in our altar living room with a looping video of the path that Alex last walked on Bernal Heights Park at sunset. At the end of the video, we catch a glimpse of Alex Nieto on his 28th birthday, seventeen days before being killed by police. The video loops much like the effect of trauma, but this altar is not only about loss. This altar is about Alex’s legacy as a community organizer, Buddhist, family-oriented young man, and an intellectual and artistic spirit. This altar is about those who remain living and speaking for him, his family and his affected communities, the underdogs who nobody sees.

<iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/110516035" width="640" height="360" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

The Twilight of Alex Nieto

Video: Co-directed by Adriana Camarena and Ivonne Iriondo

The day after the altar exhibit opened at SOMArts, on October 11th, Alex’s Giants shirt was stolen from its hanger. The shirt was a keepsake of his brother Hector. When I told Elvira the bad news, she responded, “Adriana don’t worry. These are just material things. We will overcome this obstacle like every other obstacle that they have thrown in our path.” Elvira was referring to SFPD’s attempt to murder Alex’s character, but also a period of vandalism of Alex’s permanent memorial altar on Bernal hill. On the sidetable in our SOMArts altar, I placed a coffee cup with an image of the sunrise twilight on Bernal Hill. This image was taken during a time when volunteers spontaneously set up vigils through the night and into the dawn and through the middle of the day and back into the night to fend off a moronic vandal who would throw altar items down the side of the hill. In the spirit of mischief of Día de Muertos and taking a cue from Elvira, we chose to believe that the Giants jersey was spirited away by Alex who needed it for the pennant race. That day, October 11th, the Giants won their first game against the St. Louis Cardinals. (Yo, Alex! Your brother Hector would really like a replacement shirt though.)

Twilight over the Mission, an image taken by A.Camarena during a sunrise vigil to ward off a vandal attack on Alex’s Bernal Hill Memorial site. This image was imprinted on the coffee cup placed in the altar.

Photo: Adriana Camarena

III. Tipping the playing field

A homicide by police breaks a family’s peace far beyond the loss of a loved one. A homicide by police thrusts a working class family into activism over- night, because the first thing a family victimized by an officer-involved homicide notices is that the character of their beloved is being butchered by police spokespeople in the mass media. Police tip the playing field to their advantage by controlling the release of the story to the media, in a manner aimed at dis- suading public interest in the shooting. By law, police officers can only shoot if there is a justifiable threat to an officer’s safety or the safety of another person. Therefore, police narratives always describe the victim as “a threat.” As if following a script, police version of events will describe the deceased as having pointed an object or appearing to reach for an object that may or may not be a weapon, but which supports the narrative of a threat to which officers “in fear for their lives” shoot deadly rounds.

Police version of events will also always describe the homicide victim as threatening, most often using facts and half-truths that are irrelevant to the cir- cumstances of the shooting. For example, in the case of Alex Nieto, a restraining order issued against him was referenced immediately by SFPD to the media and at the Town Hall Meeting, while failing to mention that Alex held a prior restraining order against the man in question (Vega, a formerly convicted felon.) Alex had never been arrested in his life. Only after Vega violated the restraining order, which ended in a physical confrontation, did Vega seek a restraining order against Alex. (Possibly, as a legal tactic to cover his violation of the original restraining order.) In the face of media manipulation by police, families and and friends victimized by an officer-involved shooting are left with one recourse: Restore the memory of their beloved.

Family and friends march in protest on Bernal Hill.

Photo: Adriana Camarena

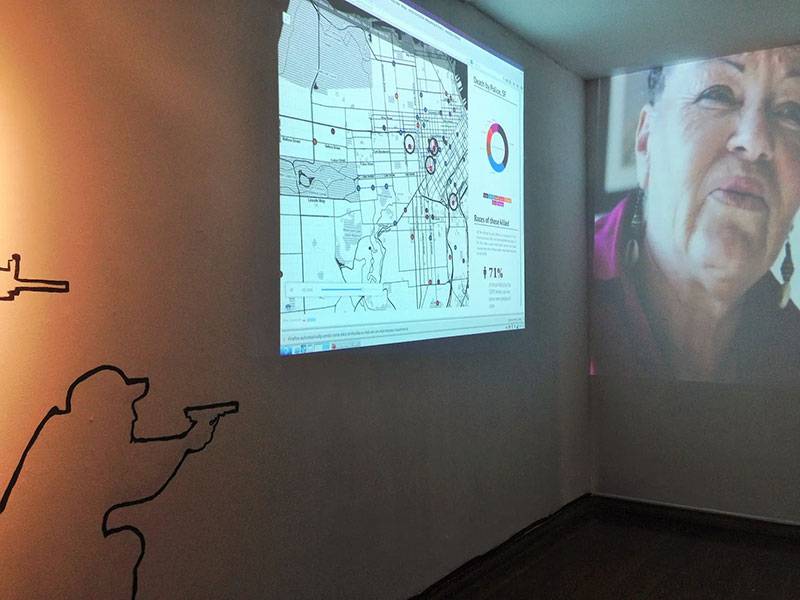

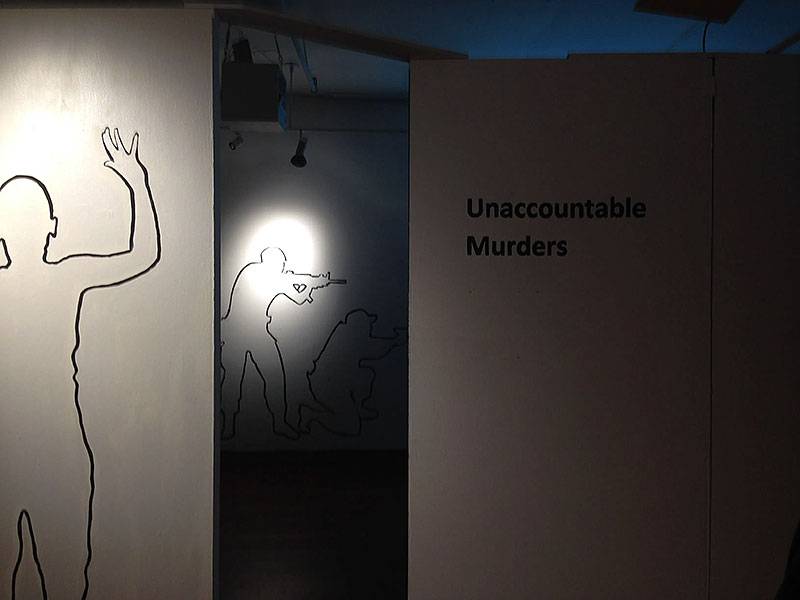

IV. Unaccountable Murders

Over the extended Columbus Day weekend (October 11th-13th), we begin readying the walls of another altar. Our altar at the Mission Cultural Center for Latino Arts is titled “Unaccountable Murders: Counting and recounting homicides by police in San Francisco,” a collaboration of filmmaker Ivonne Iriondo, activist and artist Erin McElroy, and myself. Erin McElroy is best known for her work with the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project (AEMP), which gained notoriety for mapping out the escalating crisis of Ellis Act Evictions. However, after Alex Nieto was killed March 21, 2014, the AEMP felt compelled to map out known fatal officer-involved shootings since 1985 in San Francisco.

For many, the death of Alex Nieto was a “death by gentrification,” because the police was called to the hill by an unnamed dogwalker, who many suspect to be a techie newcomer to the neighborhood. Many suspect that Alex was profiled as dangerous simply for being working-class and brown on Bernal. Paraphrasing Alex’s best friend Ben Bac Sierra, if Alex had been white (and not Latino), he would have been approached as an off duty police officer or as the security guard that he was, and an avid 49ers fan, instead of as a gang member implied by the mention of his nice red jacket. Dispatch from that evening reveals police officers hunting him without any intention towards investigation: “He is walking inside the park…” “There’s a guy… way up the hill walking towards you guys…” “I got a guy right here…” “Shots fired! Shots fired!”

The “murder map” created by AEMP shows that 71% of those killed by the SFPD, since 1985, were people of color. Yet perhaps most shocking is that 41% of those killed by the SFPD were black, when only 6% of the population of San Francisco is black according to the 2013 US Census. Racism seems inherent to police shootings everywhere, however, the more subtle connection is about the role police play in protecting private property.

The altar at MCCLA asks the public to express thoughts or comments on the wall by providing two probing questions: “What does (or who do) police protect?” and “How do we end police impunity?” For the first one, a definition of police is also provided:

po•lice /pəˈlēs/ noun A police force is a constituted body of persons empowered by the state to enforce the law, protect property, and limit civil disorder.

The altar walls continue to shift with the days as public comments are aggregated. A few commentators agree with this definition by pointing out that police protect “themselves” or the “state,” but I’m waiting for the commentator who will hone in on the relevance of having a state armed force with a primary duty to protect property, because by nature of the institution, police end up policing the have-nots versus the haves. Thanks to the residual history of conquest and colonialism the have-nots tend to be people of color, and more generally low-income minorities, who are racially or ethnically discriminated against. Police also exist to protect against civil disorder towards the state, should anyone have the uncomfortable idea that there is a problem with the foundations of a state poised to promote and protect the hierarchies of capitalism.

Our MCCLA altar “Unaccountable Murders” includes a video interview of Mesha Monge-Irizarry, contributed by Ivonne Iriondo. Mesha is the mother of Idriss Stelley, a 23-year-old young man who was killed by nine SFPD officers, when they shot him 48 times at the Metreon in 2001. After the death of her son, Mesha became a ferocious advocate against police brutality, and established the “Idriss Stelley Foundation” in honor of her son. The foundation provides free, confidential services to biological and extended families whose loved ones have been disabled or killed by law enforcement. This is a critical service considering that cities do not acknowledge police shooting victims as victims of crime. While in San Francisco therapy services are offered to any family victimized by a homicide, receiving services from the City that the family will likely fight in a legal case might not be the best environment for recovery. Mesha is a veteran first responder to families facing a crisis over a police brutality incident, and a pain in the ass of SFPD.

Walls of “Unaccountable Murders” with “Murder Map” by Anti-Eviction Mapping Project, and documentary of Mesha Irizarry by Ivonne Iriondo.

Photo: Adriana Camarena

All these thoughts loomed large in my mind, as I continued to paint silohuettes of police with weapons drawn on the altar walls, on Columbus Day, in the Mission, which name itself echoes a long history of armed enforcement of outsider claims to land.

Unaccountable Murders, (altar installation), MCCLA, 2014 by Adriana Camarena, Ivonne Iriondo, Erin McElroy

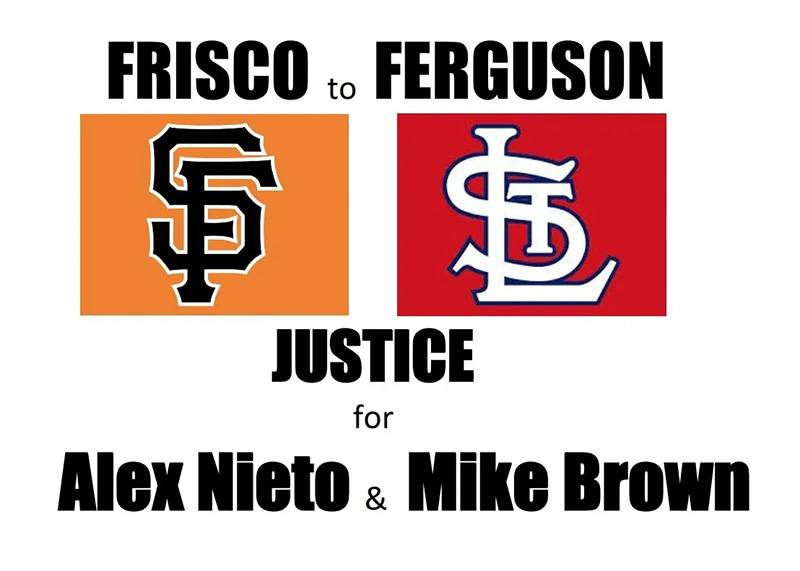

V. Giants for Justice

On Wednesday and Thursday, Refugio, Elvira and I joined local activists, artists, and youth coordinating through local organizations, friends from the PICO Network (who had been in Ferguson), as well as peeps from Stop Mass Incarceration at the Willie Mays plaza outside AT&T ballpark. We all wore our Giants colors, mixing passions for social justice with passions for baseball. We all love to belong to something together! Something bigger than us all, and that includes raising awareness about injustice. Organizers had made a colorful banner that read “Step up to the plate against police brutality!” and we held our big black and white banner “Justice for Alex Nieto.” Together we chanted: “Giants for Justice! G-I-A-N-T-S for JUSTICE!” and “Step Up to the Plate, End This Police State!” On Thursday, we were back out again before the game. This time our big banners had literally gone sailing in McCovey Cove with an impromptu justice flotilla. So we held smaller printed signs bearing messages such as “Frisco to Ferguson, Justice for Alex Nieto & Mike Brown.” Many passing fans (from St. Louis and San Francisco alike) raised their hands in solidarity to the chant of “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot!”

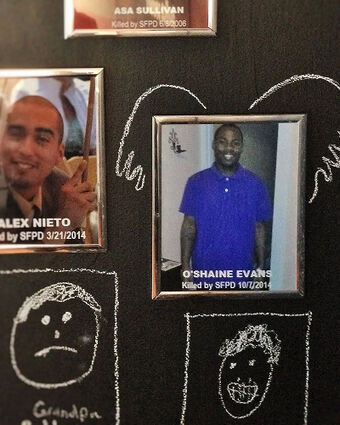

Photo: Adriana Camarena

In the saddest coincidence of the playoffs, a new family joined our ranks at the ballpark with their newly sharpied signs: “Justice for O’Shaine Evans.” On October 7th, after the Giants clinched the win against the Washington Wal- greens (Nationals) and fans partied around the ballpark, O’Shaine was killed by Officer David Goff blocks away at Jack London Alley and 2nd Street. According to the police version of events, O’Shaine was in the driver’s seat of his car, when two friends got out to break into a Mercedes SUV and steal a laptop. Undercover cop, David Goff —who was supposedly part of a sting operation in this area known for car break-ins— followed them back to the car and allegedly, from afar and in the dark, saw a gun on O’Shaine’s lap. This prompted Officer Goff to identify himself as police and demand to see O’Shaine’s hands. Allegedly, O’Shaine pointed a gun at him, which made Officer Goff fire seven rounds into the car.

A Town Hall meeting was organized by SFPD in the days after, but they failed to invite the family of O’Shaine Evans. His brother Troy found out about the meeting accidentally from a reporter seeking comments, so the family attended all the same. At the Town Hall meeting, the gun was described by Chief Suhr as unloaded and known to be stolen out of New York State. Family and friends of O’Shaine are puzzled because they never knew him to have a gun, and questioned why a police officer unloaded seven bullets at the car, killing O’Shaine with shots to the heart and an execution-style shot to the top back of the head. (The family viewed the body at the morgue, which is why they know at least about these shots.) The more important point, however, is that O’Shaine Evans was killed because of a stolen laptop. His death underscores that police feel justified killing to protect property. Consider also Mike Brown, who was killed in Ferguson by Officer Daren Wilson, who detained him after he allegedly stole something from a convenience store. Consider Kenneth Harding Jr., 19 years old, shot to death in San Francisco for running away from officers, because he didn’t want to be ticketed for lack of a $2 MUNI transfer. His mother Denika has spent countless hours teaching public school children not to run from police, so that she may save lives.

At the Town Hall meeting for O’Shaine Evans, Chief Greg Suhr did his best to destroy 26-year-old O’Shaine’s character by mentioning that he had a juvie record (failing to mention this was from when O’Shaine was 12), even though he did not have a criminal record as an adult in San Francisco or anywhere else. Chief Suhr failed to mention or investigate that O’Shaine was a devoted boxer in training, with an extremely chill temperament, who loved to read National Geographic and Sports Illustrated on a daily basis and study boxing matches at home. It is unbelievable to his family that O’Shaine would risk his life by pointing an unloaded gun at an officer with a loaded gun pointed at him. The Jamaican-born family often talked together about the importance of calm behavior around police in the United States, knowing police have a tendency to shoot black folk. His mother is a lifelong school security guard in the U.S.

Outside AT&T ballpark that Thursday afternoon, October 16th, Elvira and Refugio gave Troy a hug. Tears were not exchanged, only a solid gesture of understanding. Drowned in the deafening roar coming from the crowd inside the stadium, Refugio took in the Willie Mays plaza and said, “Alex loved this. He would have loved being here.” Elvira nodded in agreement.

The action ended and with the game underway we walked around to ob- serve the “justice flotilla” in McCovey Cove bearing banners against police brutality from Frisco to Ferguson. With the sailboat in perfect position for TV coverage, I started wishing hard for a Giants splash homerun. Juana and others went off to enjoy the game, and the Nietos went home, but Troy and I stayed to talk. I noticed that Troy was wearing an A’s green hoodie, and I was wearing my SF orange hoodie, and gave him attitude. He tilted his head with pride, “Hey, I’m from Oakland.” We laughed and Troy continued to explain why the SFPD version of his brother’s killing didn’t add up. Deeply immersed in his storytelling, we were suddenly interrupted by a rising roar. I remember the moment in slow motion. The fans around us tilted their heads up, searching for a ball, while the people above us in the bleachers started following the arc of Joe Panik’s hit to the deep corner of right field. Every gaze and everybody began swiveling to converge around a point somewhere above Troy and me. Instinctively, Troy grabbed my shoulders and pulled me in tight, bracing for the projectile that was surely rocketing towards us, but Panik’s homerun never cleared the stadium. The fountain pillars shot water into the air to celebrate the homerun. Later that night, the Mission District exploded in celebration as the Giants historically made their way to the World Series.

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/yUx29PceE2Y" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Video: Adriana Camarena

VI. October Together, the new normal…

On Saturday October 18th, I spent the afternoon with the family of O’Shaine Evans in deep Oakland helping them create a record of police version of events, much in the way we Alex Nieto supporters have done on our website to help keep the public informed and battle misinformation. While I was there, Jonathan Melrod called Troy. Melrod is an activist, who is part of the Justice for Andy Lopez Coalition (the 13 year old who was killed by Officer Gelhouse on October 22, 2013 in Santa Rosa), and also the lawyer representing the family of Yanira Serrano-Garcia (killed by Deputy Menh Trieu in Half Moon Bay on June 3, 2014.) Troy and his mom were struggling to find a lawyer, and Melrod was helping connect them to one. The family was already in contact with Mesha, as well as with George Russell, who makes buttons for families who lose loved ones to police shootings.

Sitting in O’Shaine’s family living room, watching Troy fatigued by grief and responsibility, I turned to his auntie visiting from Canada, and whispered “Troy needs to get some rest.” To which in all her wisdom, she responded, “This is the new normal.”

Altar wall as part of “Unaccountable Murders” at MCCLA, 2014 Day of the Dead altars.

Photo: Adriana Camarena

October Together is the new normal for victims of police brutality…

On October 22nd, across the Bay Area, organizers responded to the National Day Against Police Brutality called forth by October 22nd Movement nineteen years ago against police brutality, repression, and criminalization of minorities.

On October 22nd, supporters of Andy Lopez, 13 years old, commemorated his killing exactly a year ago in Santa Rosa.

On October 22nd, the family of O’Shaine Evans, 26 years old, held his funeral and burial in Oakland.

On October 23rd, the family of Yanira Serrano-Garcia confronted Sheriff Greg Munks in Moonridge for her fatal officer-involved shooting, when the family had explicitly called for mental health medical assistance.

On October 21st, 2014, family and supporters commemorated Alex’s 7th month anniversary of being killed by SFPD, on Bernal Hill, with no answers yet as to the names of the officers who killed him, the original 911 call, police reports, or witness statements.

In October we build altars.

In October, the underdogs come together to remember and fight for our beloved dead killed by police. You may not see us misfits coming, but much like the wildcard Giants, we’re fighting a righteous cause against abuse from the royal blue!

Justice Flotilla, October 2014, outside Giants stadium in McCovey Cove.

Photo: Adriana Camarena

VII. List of Bay Area homicide victims killed by police

For more information about specific police homicides in the Bay Area or NorthCal please refer to the justice causes below, each of which has a website or facebook page. Except for the case of Oscar Grant, no officer-involved shooting has resulted in a criminal trial. (This is an incomplete list):

Idriss Stelley Foundation, Idriss Stelley (23yrs) killed 6/12/2001, San Francisco

Justice for Asa Sullivan (25yrs) killed 6/6/2006, San Francisco, (Brother tells Asa’s story)

Oscar Grant Foundation, Oscar (22yrs) killed 1/31/2009, Oakland

Justice for Kerry Baxter, Jr. (19yrs) killed 1/16/2011, Oakland (article)

Justice for Valente Galindo (47yrs), killed 12/15/2011, San Jose (article)

Kenneth Harding, Jr. Foundation, Kenneth (19yrs) killed 7/16/2011, San Francisco

Justice for Alan Blueford (18yrs), killed 5/6/2012, Oakland

Justice for Andy Lopez (13yrs), killed 10/22/2013, Santa Rosa

Justice for Eroll Chang (34yrs), killed 3/17/2014, San Mateo

Justice for Angel Ruiz (42yrs), killed 3/20/2014, Salinas (article)

Justice for Alex Nieto (28yrs), killed 3/21/2014, San Francisco

Justice for Osman Hernandez (26yrs), killed 5/9/2014, Salinas

Justice for Carlos Mejia (44yrs), killed 5/20/2014, Salinas (video)

Justice for Yanira Serrano-Garcia (18yrs), killed 6/3/2014, San Mateo

Justice for Frank Alvarado (39yrs), killed 8/11/2014, Salinas

Justice for O’Shaine Evans (26yrs), killed 10/7/2014, San Francisco