Unsettled: Coded World

Historical Essay

by Adriana Camarena

Originally published in El Tecolote September 6, 2018

Photo: Adriana Camarena

Joel Uicab is a 22-year-old coder living in the tech-gentrified Mission. He is also a Mayan-Mexican immigrant and an award-winning Latino student, who has been labeled a “gang-affiliate” by the criminal justice system. He scaled the wall at the border when he was 11. Now, he is trying to life-hack his way out of the school-to-prison pipeline that keeps his people down in the Land of the Free. That’s a lot of code to break!

Leaping the Wall

Scaling the border, he lost a shoe and his black plastic bag with his identification and school papers. In the hours that followed, Joel would lay hopeless under a tarp, hiding from the Border Patrol that hunted his group. Convinced that his lost papers meant that he would not be able to enroll in school, he asked himself, “Was there any point in going on now?”

Later, smashed up against each other in the back of a van for a 15-hour ride to San Francisco, Joel and his cohort of survivors would finally relax. This is when one of them opened the black bag he picked up on the run and realized it did not hold his papers, it held Joel’s. The dream was back on.

When he and his cousin were dropped at the foot of the building where his parents lived in San Francisco, his father and mother came out to meet them. His father asked, “How was your crossing?” Joel stoically responded, “It was alright.” His mother gave him a heartfelt hug, and his father declared, “Well, we have to go off to work now.” It was 5 a.m. in the New World.

‘Memoria del Futuro’. Raúl Cruz / RACRUFI

Decoding Language

“Everything was code for me,” explains Joel, “Because I didn’t know English, I had to decode everything.”

On his arrival, Joel was enrolled by his parents in Everett Middle School in the Mission District. His teacher, Ms. Alicia Medina, encouraged him to draw images for every new word that he learned. “I had to create a dictionary, word by word, of what people said. I had a notebook full of characters!”

The notebook was pitched out in a housecleaning by his cousin. I am left to imagine Joel’s lost pictionary as a contemporary Mayan Codex for students of English as a second language, or in Joel’s case, as a third language, since he is Mayan from the state of Quintana Roo in Mexico.

Speak English

Joel made a friend at school: Christopher Arreola from Mexico City. Shaking his head with pride, he exclaims, “He’s my nigga!” After school, they would head to Dolores Park where they would push each other to speak better English in the seclusion of their companionship. “No more Spanish when we get to the park!” they promised each other. “Pronounce it right! Open your mouth,” Joel would egg Christopher. Christopher would shoot back with his better written English.

Back at home, late in bed until 1 a.m., or even riding the J-line to school, Joel commandeered his mom’s flip phone to access “Inglés Sin Barreras” (English Without Barriers) or surf internet dictionaries for words he didn’t know or needed to translate. “You’d have to activate the little blue and green planet icon to access the internet. You also had to click, click, click for everything!” he reminisces, making a two thumb typing gesture.

Meanwhile, Ms. Medina—the underpaid teacher aide-para, the genius hero of our story—asked the newcomers to meet her on Saturday and Sunday at the school. “She wasn’t even getting paid extra for us,” tells Joel. “It was all so we could pass our test.”

In 2010, three 11th grade students out of a class of 27 received a full five score on their California standard assessment tests at Everett Middle School. The three were Joel, Christopher and Maria Campos, all part of the group coached by Ms. Medina.

Joel received the school’s César E. Chávez Award and made the honor roll.

MySpace

The other reason Joel’s English was improving was because he was on MySpace, the most successful social media experience before Facebook. How else was he supposed to communicate and flirt with American teenage girls, if he lacked the vocabulary to chat them up properly? The format also allowed him to think about what he wanted to say, and take the time to find the right words.

Computers with visual art display welcome guests inside Noisebridge, on Sept. 12, 2018.

Photo: Adriana Camarena

A necessary consequence was that, besides learning English on his mom’s flip phone, Joel taught himself fourth and fifth languages: HTML and CSS, coding to customize his MySpace profile, layout and song. Programmers will learn at least three to a dozen different programming and scripting languages in their trade. In 2016, NPR Latino and Business Insider reported that MySpace is the most often cited reason given by women, including Latina youth, about why they code and work in tech. As one Black Twitter user @StillEWills remembered, “Myspace had us all coding and not knowing we were flirting with a six-figure skill.” In hindsight, MySpace appears as a unique egalitarian coding space that showed off everyone’s capacity to learn and wield a new common language.

Then the prefabricated interfaces of Facebook came along and made us all—literally—none the wiser.

You Have Math In Your Blood, Burros

“I like numbers. Mayans like numbers. We invented the zero. I inherited all that,” he says, matter-of-factly. Joel learned math at a young age in Mexico, both at school and at home. “My mom would put maizitos, corn kernels, out on the table as she cooked. It helped me visualize how numbers added up.” Joel’s dad had a sterner method. “My Dad insists that I add up everything in my head. He’ll say ‘Don’t you have a cabeza? Didn’t you go to school? In my time, there wasn’t paper, not even ink!’”

A member of fifth cohort of dev/Mission, sits in his first workshop at 360 Valencia St, on Sept. 10, 2018.

Photo: Adriana Camarena

After graduating from Everett, Joel enrolled in Mission High School. In his junior year, he enrolled in Computer Art Class. Ed Martinez and his brother Jesse, founders of Latino Startup Alliance, volunteered their time to teach computer literacy, contributing their maizito so to speak, towards toppling the race and gender digital divide in the tech industry.

“Ed, he saw something in me,” says Joel, “He started teaching me how to code.” Coding made sense to Joel. “You give a computer instructions, and it can only do what you say. I related it to my life. For every action, there is a consequence. If the syntax [that is the spelling and grammar of a programming language] is not correct, there will be an error.” Learning to code is therefore also about learning to find the bugs (mistakes) in the syntax of a code, and debugging the instruction. “Ed wouldn’t give me the solutions… If I had a very hard time, he’d only give me a hint.”

Joel learned to code through information sharing on the one hand, and autodidactic curiosity on the other. His mom bought him a computer. “I took that computer apart 500 to 1,000 times, and put it back together as many times,” says Joel. What Joel did to his computer is the original meaning of hacking: taking apart a technology, figuring it out, and trying to make it better. One day his computer caught a virus and a neighborhood guy helped by tragically reformatting it and erasing every bit of beloved information Joel owned, including early photographs from his arrival to San Francisco. With dogged true grit, Joel was back on the flip-phone, learning the meaning of “tab” and “window.” He recovered the thumbnails first, and then learned about pixelling. Pixel by pixel he recovered his digital memories. “The flip phones were the shit to me.”

Later on, Joel would find Noisebridge, an anarchist hacker space on 2169 Mission Street, 3rd floor, where he would plop down at a corner for hours, reading tutorial books on computer programming languages. About the same time, he enrolled in Mission Techies at MEDA, which focuses on teaching adults, 18 years and older, an array of IT skills.

At Mission Techies, Joel improved his HTML, CSS and PHP skills, and learned the ZWIFT programming language. Part of the curriculum at Mission Techies also takes students to visit a significant number of Silicon Valley tech company campuses.

“We visited the new Infinity Loop Apple headquarters in Cupertino, and the Google campus in Menlo Park… We rode bus shuttles from the Mission over there. At Google, I got in a self-driving car that took me from Building A to Building D. We ate an awesome lunch at the free buffet. Did you know there are free bikes that you can just grab and go anywhere? No one would call the cops on me for stealing, because there is no need to steal. I felt entitled to all of it. I desired having access… Then I went back to the Mission and just thought, why does it work there and not out here in real life? Why if it’s exactly the same tech professionals coming back to the Mission, who are not greedy there, who are sociable there, why can’t it be the same in the Mission?” Joel asked.

Logic Gates

The digital revolution was built on binary logic. Engineers built computers to interpret any character they typed as a series of zeros and ones. Zeros and ones were further assigned logical values of “false” and “true.” This allowed engineers to make computers that could perform Boolean algebra operations. In Boolean algebra, two binary values are given—each one can be either false or true—and one of seven basic logic operations applied to them: “and,” “or,” “not” “not-and,” “not-or,” “exclusive-or,” and “exclusive not-or.” These operations are also known as “logic gates.” Without going into lots of detail, actual physical logic gates exist inside computers that compute electric zeros and ones. These binary transactions are the basis of all modern computing and programming.

The basic logic operations of a computer mimic human logic, except that when computers equate zeros and ones as “false” and “true,” they are not making any moral judgement about zeros and ones. In this, computers are very unhuman-like, because we guide our everyday conduct by moral value systems that define access to the gateways of power and wealth. In the binary value system that we live in, one race and gender has been given greater value.

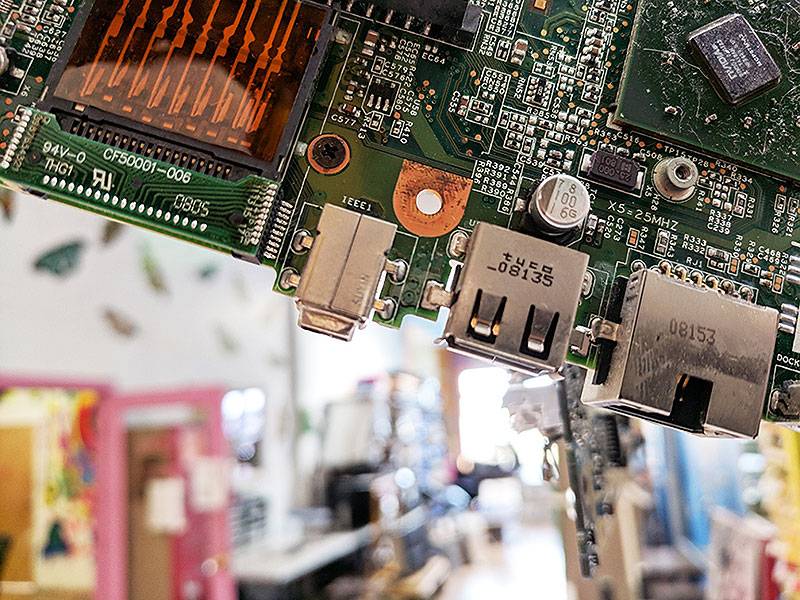

A detail of a mobile art piece made with computer circuits hangs inside the Noisebridge “hackerspace” in the Mission District, on Sept.12, 2018.

Photo: Adriana Camarena

In 2013, three Black women founded the Black Lives Matter movement (#BLM) in California. A year later, #BLM hit the national stage, in the wake of the 2014 Ferguson uprising in fury over the killing by police of Mike Brown. By saying that Black lives have true value, and calling for a Black-led and centered movement, #BLM bumped White lives off their pedestal of highest human value. The simple syntax of “Black Lives Matter” fried the circuitry of the White supremacist right—“Off=0=False=White, On=1=True=Black.”

Then in 2016 Colin Kaepernick kneeled and broke the internet.

For other racial minorities the binary script is even more problematic, because it leaves little space to claim the value of our own lives, without clumsily wandering into a national race war that disproportionately impacts Black people. In the binary national script, Latinas and Latinos, Asians, Arabs, and others are human UFOs floating between the polarities. We are the unexplained dark matter. Only Native Americans are more invisibilized, more impacted than any other life. The history of original peoples, marred by genocidal violence, is the red pill that hacks into the founding matrix of modern democratic capitalist economies across the Americas.

You Belong Here

Two weeks ago, I visited Leonardo Sosa at his start-up nonprofit called dev/Mission at the Valencia Gardens housing complex at 360 Valencia St. Sosa arrived in San Francisco in 1985, at the age of 15, a refugee of the Guatemalan civil war. His life, his family, and his skills from Radio and TV Trade School were his sole possessions. After hacking English, getting a high school degree, and making a baby with his high school sweetheart, Sosa had all but given up on a career in tech. He earned well enough in a union job at Safeway to support his young family, but as life would have it, he got injured. The union gave him a choice: cash out or go back to school. He chose to attend the Mission Language and Vocational School. Soon enough he was teaching there, because old school hackers share what they know. It’s almost a code.

A banner seen at the entrance to dev/Mission located at 360 Valencia St., on Sept. 10, 2018.

Photo: Adriana Camarena

Leo sought to work in the tech sector of Silicon Valley: “I applied for the jobs, I had the programming certifications they required, I had the experience they demanded, but it was always Caucasian males getting the jobs. They never got back to me.” Leo knew what was up: “White=True=1=On=Hire ∴ Latino=False=0=Off=No Hire.”

White male-dominated work environments insidiously perpetuate barriers to access for women and people of color because they entrench the moral value of White men over other humans. A 2017 report by Ascend Foundation on race and gender disparity in Bay Area tech companies, also found that recent efforts to increase diversity showed that companies value Whiteness: White women were more likely to become executives than Hispanic men by 31 percent, 88 percent more likely than Asian men, and 97 percent more likely than Black men. Meanwhile, the report found that between 2007 and 2015 the race and gender gap for minority women had actually worsened across the board. Perhaps the most dramatic finding is that Asians in tech, who comprise 29 percent of all workers in top tech companies, only have the illusion of success. They are the racial group least likely to ascend to executive positions, with Asian women the least likely of all people.

Leo Sosa likes hacking systems, and he is relentless about getting youth of color to enter tech as early as possible. “Boot Camps are fine, but those programming skills need to be offered to every single person, for free,” he says. Over the years, he has participated in large scale nationwide campaigns and hyperlocal neighborhood efforts to that end. A few years ago, he founded Mission Techies at MEDA. Seeking to reach a still younger crowd, last year he founded dev/Mission through the Mission Housing Development Corporation, which serves youth 16 to 24 years of age. The program is starting to establish satellite projects in other public housing sites in Visitacion Valley and Hunters Point, and also Oakland.

A giant banner at the entrance of dev/Mission declares, “You Belong Here.” Sosa wants the youth walking through the door to see and receive that message. “I don’t sugarcoat the truth for them. I prepare them to face the possibility of harassment at work. Some of these youth might have tattoos and other reasons to be further racially profiled. We also talk about the ‘soft skills’ that they will need to succeed in a corporate environment.”

I entered dev/Mission with the same snarky attitude seen in Boots Riley’s recent film “Sorry to Bother You,” knowing that the tech sector is no golden egg. After sitting in on the first day of class of a new cohort, the young women and men of color reminded me, however, that they need and want to make a dignified living in this unforgiving world.

Hackers and Hats

Old Western films traditionally give the good guy a white hat and the bad guy a black hat. This meme was translated to hacker parlance to identify “white hats” as good hackers and “black hats” as bad hackers. White hats are considered to somewhat represent the original hacker culture that developed from the ‘50s to ‘70s: People curiously and playfully figuring out how computer systems function and can be manipulated, and sharing this information with each other. Today, large corporations—Twitter, Facebook, Google, MasterCard, Western Union, etc.—all employ white hats to identify vulnerabilities in their systems and take preventative actions against unwanted intrusions.

Black hats—the adversaries—exploit weaknesses in a system for nefarious reasons or their own personal gain. “Gray hats” are somewhere in the middle, many hacking for the joyride and bragging rights of illegal breaking and entering. Then there are the “red hats,” who are like white hats, but they work for governments. There are also “hacktivists,” but they’re not given a hat. Rather, they are masked crusaders with a political or social change agenda, like Anonymous, who has used the Guy Fawke’s mask in attacks on the CIA and the Ku Klux Klan.

Graffiti in chalk over a marketing poster for the film “BlacKkKlansman,” seen on 24th and Street near Folsom Street, on Sept. 7, 2018.

Photo: Adriana Camarena

For youth in inner cities there are other hats and colors that may come into play. Schooled in the Mission, Joel started taking an interest in blue hats. It happened almost accidentally after Joel brought his Mayan chops to a school yard fight. The fight ended up placing him on the same side as another student I will refer to as “O.” O. would always arrive “blued-up” both from the bruises he sported and the all-blue clothing he wore. Needing friends, O. started sitting with the two newcomers Christopher and Joel.

By high school Joel just wanted to be with the gang: “I was just a pee wee, a wannabe, I would be sent away by the older guys kicking it in Dolores Park, smoking weed and drinking. I started saving lunch money so I could buy some weed. I wanted to be from the block.”

“Why did you want to be with them?”

“Because I didn’t have anyone to talk to!” he exclaims. With his parents working hard to cover rent, save money, pay debts, put their children through school, and send money back home, they were simply never there. “I often got high or drunk after school, but by the time they came home at 10 p.m., I just pretended to be asleep in bed.”

This is such a common narrative among immigrant Latino families—their sense of familial responsibility leading both to their over-achievements as workers and the neglect of their children—that organizations such as Horizons Unlimited dedicate resources to educate immigrant parents on the challenges faced by their children. Latina and Latino youth are also acutely aware of money shortages at home. Taking after their parents, they rather figure out a hustle of their own, than be an extra burden on their caretakers.

Joel took up a temp job, cutting school in the morning but returning before noon: “From 8 a.m. to 11:20 a.m. I was on the block making money.” He also learned the most valuable street codes: “show respect” and “no snitching.” In the afternoon, he went back to school to learn Javascript.

In Prison with Python

Joel eventually got into a fight over colors that landed him in juvenile detention doing a nine-month sentence. “I started school in jail, but they were doing kindergarten math in there!” With assistance of a lawyer and skilled law clerk, Joel was able to convince the judge to allow him to teach himself to use the Python programming language for cryptography and security. Curiously, the school filed charges while he was in detention alleging that Joel had hacked the school system, but his legal team proved it couldn’t have been him. “When I got out, my P.O. didn’t want to let me enroll in Mission High School. I was determined to graduate from there. I convinced the principle to let me back in.”

Joel clawed his way up the wall again, pulling double and triple school shifts, after-school hours and night school, 12 hours a day, to graduate from Mission High School with a 3.2 GPA. Everyone he loved showed up for his graduation.

The dream was back on.

Ms. Betty Goes On Vacation

For his final school year Computer Art Class project, of all things, like a true white hatter, Joel created the electronic Student Tracker system that is still in use today at Mission High School. The Student Tracker substituted the reams and reams of paper used by the school guards to record late arrivals, early exits, and paper passes that they handed out all day long to students visiting the bathroom, lockers and other offices. These registries then had to be transcribed by the school attendance clerk Ms. Betty, followed by a hundred personal phone calls to respective parents about any out of line behavior. With the electronic Student Tracker, the guards began using barcode-handguns and mobile apps that sent and compiled information in a file on Ms. Betty’s computer. The computer would then send out an automatic pre-recorded message with her voice to parents to inform them of what their child was up to.

This is how the school avoided having to buy an extravagantly priced and licensed system, trees were saved, and Ms. Betty finally went on vacation.

Of course, Joel made sure the Student Tracker went online after he graduated.

Taquero Guardian

While Joel’s parents were off working double and triple shifts every day from 5 a.m. to 10 p.m., Joel would take himself to school and back, and learn from the world around him. The taquero near his home would chat him up, acting as a surrogate parent. He’d nod towards the homies at the corner and say, “You came to study, right? That’s why you came, right? Don’t you be kicking it with them.” Teenage Joel would reaffirm his commitment to the taquero.

Shaking his head, Joel confessed to me, “For years I couldn’t even stand near the taquería with my friends. I didn’t want to disappoint the taquero.”

The taquero was not his only guardian. His mom and dad stepped up to the plate, and there were lawyers, parole officers, therapists, O.G.s, and a torrent of community social workers that along the way showed him that despites the odds, he still had choices.

I accompany Joel back home after our talk, avoiding any circuitous route that the ankle bracelet he wears could construe as a violation of his sentencing. I can’t help myself, and ask, “How does it feel to be tracked like your Student Tracker?” He just cringes and grabs his head, “Fuck! I know!”

Debug Yourself

Coming out of Mission High, life was looking up for Joel. He received a special immigrant juvenile status. He had papers, at last! CARECEN (Central American Resource Center) took him in and coached him in youth leadership roles. He even travelled to Nicaragua to learn first-hand about the criminal justice system there. Then he came back home, and he didn’t have enough money to pay rent. Joel started hustling. It didn’t seem like nothing, he was enjoying the cash, the clothes, the lifestyle, the attention from “friends,” and then he broke a street rule: he started using his product, first cocaine, next meth.

Joel Uicab, a programmer at HOMEY poses for a portrait on on Aug. 28, 2018.

Photo: Adriana Camarena

Behind every addiction is a great sorrow. I asked Joel about his. “It was the contradictions that got to me. On the one hand, I was working at CARECEN trying to be better for others. On the other hand, I was poisoning my people.” His situation spiraled out of his hands, and he ended up locked up again.

Joel was lucky. His stint in the jailhouse was brief, and the staff at [[|HOMEY Mural 24th and Capp|HOMEY (Homies Organizing the Mission to Empower Youth)]] believed in his desire to get back on track, enough to hire him. At HOMEY, Joel provides tech support and youth computer literacy skills. He also practices HOMEY’s mission of supporting other young people like himself, with hope, empowerment, leadership, culture and love.

Joel hasn’t given up on his dream of working in tech, but right now he is working on “debugging himself.” “How?” I ask. “Through ceremonia, sweatlodges, and danza,” he answers. As of late, he has been meditating on his abuelito’s dying words, the same abuelito who was his caretaker in Quintana Roo before he came to the U.S., the one Joel never went back to see, even when he had the money for airfare. The word of his Mayan ancestor was, “Tell my grandchildren not to do evil. To little Joel, tell him to do good.”

About Unsettled

Unsettled in the Mission is a series of literary non-fiction essays by Adriana Camarena to be published periodically as supplements in El Tecolote through January 2019. Her writing is based on portraits of the traditional working class and poor residents of the Mission District for an exploration of Latino identities and histories. This is a collaborative project supported by the Creative Work Fund, however, the views and opinions expressed in “Unsettled” are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Acción Latina.

About the Author

Adriana Camarena is a Mexican from Mexico, complicated by an upbringing in the U.S., Uruguay, and Mexico. She became a resident of the Mission District of San Francisco in 2008. Since arriving in the Mission, Adriana began collecting tales of borders, line-crossings, and overlapping identities told by residents to provide a layered picture of this traditionally working class immigrant neighborhood in California. To learn more about the author and her work, please visit her website.