Irish Hill

Historical Essay

by Steven Fidel Herraiz

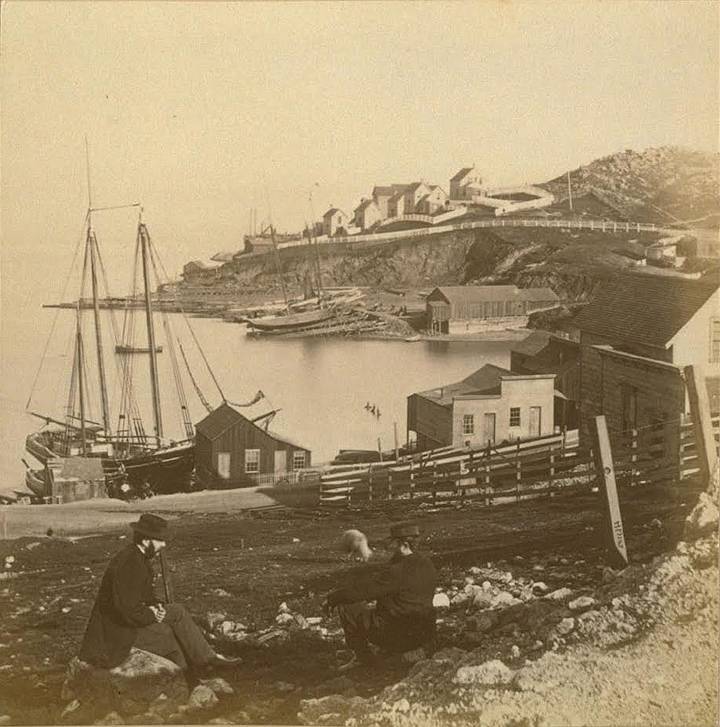

This Edweard Muybridge photo from 1862 was taken from near today's intersection of 19th and Illinois Streets looking southeast. The buildings on the hill were Irish Hill's first settlement and date from the late 1850's. These saloons, boarding houses and single family residences were on 22nd Street, which has since been excavated to just above the sea level. The small bay in the middle of the photo was filled in to provide land for Union Iron Works' Machine Shop (1883) and to extend 20th Street from today's Dogpatch to San Francisco Bay.

Photo: Bancroft Library

| During the late 1850s, Irish Hill rose to prominence as a home for laborers employed by nearby manufacturing plants. For the disproportionately male demographic which called this community home, life presented numerous challenges. Local hotels and saloons fostered a hostile environment for residents, fueling the alcoholism and organized crime that ravaged the neighborhood. The industrial development which facilitated the area’s genesis eventually orchestrated its demise, as the Union Iron Works leveled sections of Irish Hill for expansion beginning in 1897; the “Irish Mound” that remains with us today was all that survived by the 1940s. |

Ours is a city known for its hills, our beloved Potrero being one of them. In our city’s short history, those hills have been shaved off, cut into, built upon, and, in some cases, obliterated. Yet, however changed, each hill has retained its name, recognized by most San Franciscans, and at least some evidence of its residents.

All hills except for one, a mostly unknown hill that met its demise nearly a century ago, a hill we could have seen from Potrero Hill, looking east toward the Bay: Irish Hill, the Potrero’s lost neighborhood.

This photo was taken from the west side of Illinois near 20th Street in May 1918. The Bethlehem Steel Administration Building (built in 1917, still standing) is on the left. These Irish Hill businesses, in order, left to right, were a saloon, a French laundry, and another saloon. Within three months, these buildings would be razed. Today, a parking lot occupies this site.

Photo: San Francisco National Maritime Museum

One fragment of Irish Hill remains, a craggy, shorn slope of blue serpentinite rock, visible from Illinois Street. It rises gradually along Michigan Street (which no longer exists, but ran one block east of Illinois Street), between Shasta Street and Sierra Street. We know Shasta Street as 21st Street, Sierra Street as 22nd Street.

So, how can one visualize a neighborhood, with few photographs or visual markers, a neighborhood whose topography has been so dramatically altered, whose streets, buildings, and residents have disappeared nearly ninety-six years ago?

1859 USGS Coastal Survey Map showing Potrero Hill, Mission Bay (and Mission Rock out in the water), and the eastern part of the Mission District when there were two horse racing tracks occupying what is today all residential. Note the "rope walk" at shore middle left. Irish Hill is the slope near bottom of map that reaches the bay at San Quentin Point on this map.

Map: courtesy David Rumsey

Irish Hill was a seven-block square, working-class neighborhood situated between Dogpatch and San Francisco Bay between the early 1860’s and 1918. At its highest elevation of 90’, it once connected to Potrero Hill. Inhabited as early as 1861, years before Dogpatch or Potrero Hill, its development owed much to the completion of Long Bridge in 1867, which crossed Mission Bay and effectively linked downtown San Francisco to Potrero Point, a rocky promontory that jutted into the Bay at the terminus of what is now 23rd Street. This connection to the rest of San Francisco hastened the growth the large, developing industrial areas in the southeast part of San Francisco. In the1850’s and 1860’s, heavy industries, drawn by Potrero Point’s inexpensive land,, relative distance from the City’s populace, access to rail lines, and deep waters just offshore, opened there: several blasting powder manufacturers, Tubbs Cordage (a rope manufacturer), the City Gas and Light Company, (which would later become PG&E), a whale and seal oil refinery, and the Pacific Rolling Mills, the first steel mill on the West Coast. In 1883, the Union Iron Works relocated to Potrero Point, its first buildings surrounded by the steep cliffs of Irish Hill on the north, south and west.

Despite its noise and pollution, poor immigrants settled on Irish Hill because of its proximity to the industries that hired them. In 1892, the Union Iron Works employed 1.200-1,500 men, many of whom could walk to work from Irish Hill, Dogpatch, and Potrero Hill.

Irish Hill was bounded on the north by Napa (20th) Street, south by Sierra (22nd) Street, west by Illinois Street and east by San Francisco Bay. Several streets that no longer exist ran parallel to Illinois Street toward the Bay. In order from west to east were: Michigan Street, Georgia Street, Louisiana Street, Maryland Street, and Delaware Street. The rumor was that the City named the streets of the Potrero and outer Mission after states, to ease the homesickness felt by the many recent arrivals to San Francisco from other states. There were two compact, distinct areas that made up the neighborhood of Irish Hill. At the southern end, several boarding houses, saloons and sixty cottages overlooked the Union Iron Works from the 90’ hill on Sierra (22nd) Street between Georgia and Maryland Streets. One had to climb 98 steps to reach the upper part of Irish Hill. At the northern end was a small business district, built on the flatter lands near Napa (20th) and Illinois Streets, which housed more boarding houses, hotels, saloons, residences and grocery/liquor stores. Most of Irish Hill’s streets were never paved, which made traveling them after a rainstorm particularly challenging. According to Sanborn Fire Maps, some of its streets were either ‘not opened’ or ‘impassable.’ Some streets came to a dead end mid-block because of the area’s hilly terrain.

Because of the number of single men that lived there, most of Irish Hill’s businesses were private and public boarding houses, hotels, and, of course, saloons. Interviewed in 1946, Billy Carr, a sheriff’s deputy who grew up there said, “You went up on Irish Hill when you got off work and you never left it until morning.”

Places like the White House, Paddy Kearns’ Hotel, the Brooklyn House, the Mechanics’ Exchange, the Monterey House, and the Union Hotel housed, fed, and often imbibed the men of Irish Hill. At the crest of Irish Hill at Sierra (22nd) and Maryland Streets, Mike Boyles’ Steam Beer Dump hosted bare-knuckle boxing matches in the intersection every Saturday night, pitting men from different hotels against each other. The losers bought the winners five-cent steam beers at Boyles’ popular saloon. Life was hard for these men. Twelve hour work days at dangerous jobs, the loneliness of being separated from loved ones both here and abroad, and abject poverty made liquor a popular salve. In 1889, Irish Hill’s seven square blocks housed 38 businesses. One could purchase alcohol at 25 of those businesses, in either saloons or ‘sealed package houses’ (liquor stores).

This photo was taken in 1918 from near 22nd and Michigan Streets, looking north toward downtown San Francisco. Michigan Street was one block east and parallel to Illinois Street (where the utility poles are). Though it no longer exists, it was a main thoroughfare on Irish Hill. These buildings, many of them derelict, would be razed within months of when this photo was taken. A portion of the Bethlehem Steel Administration Building can be seen on the upper right.

Photo: courtesy San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park

Red Cross vehicles parked in front of buildings at foot of Irish Hill, 1918. In the background is the white office building of Bethlehem Steel.

Photo: courtesy San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park

Of course, liquor caused more problems than it solved. Crime plagued Irish Hill. Stories of the alcohol-fueled mayhem were reported regularly in the newspapers. Barroom brawls were commonplace, but stranger events took place too. There was the case of a man who ‘went insane’ (code for ‘got very drunk’) and after a three day bender had to be pulled, naked and incoherent, out of the shallow mudflats, where he’d tried unsuccessfully to drown himself. Another man blacked out while sitting in an outhouse and fell 14 feet to his death. Another poor soul died after a night of drinking and cards at a friend’s place, when he mistook the back door for the front door and fell off a cliff, landing on Illinois Street, 50’ feet below. A son got into a fistfight with his father, knocked the elder’s glass eye out, and stepped on it, smashing it to bits.

However, not all of Irish Hill’s residents were single men. According to a sampling from the 1900 United States Census report, 35% of the adults (18 years of age and older) were women. One third of them were children, 10% of whom had jobs. Seventy percent of them were first-generation immigrants; 30% were second generation. Though 55% were of Irish descent, Scotch, German, Italian, Swedish, Dutch, and Norwegian people (and one Australian) called Irish Hill ‘home.’ And it was a hard life for these people too. Newspaper articles from 1887-1892 reported:

- • Six accidental deaths, two of them job-related,

- • Three suicides (one attempted suicide),

- • Ten assaults (five with a deadly weapon),

- • Eighteen burglaries,

- • Two minor fires, and

- • One major fire.

- • Six accidental deaths, two of them job-related,

By far, the most well-known resident of Irish Hill was Frank McManus, known citywide as the ‘King of the Potrero.’ Escaping the Irish potato famine, Frank and his younger brothers set off for San Francisco in 1865. He made his fortune selling mining stocks and, according to rumors, won the Union Hotel in a card game. Wielding great power on Irish Hill, both politically and economically, he became an outspoken member of the County Republican Committee and influenced many elections. And if one wanted to get a job at the Union Iron Works, he would have to go through Frank McManus, stay at his Union Hotel, and drink at his saloon. Those who didn’t suffered brutal beatings by McManus and his thugs. But in 1885, his housing and boozing monopoly was challenged by brothers Thomas and John Welsh, who brazenly opened not one, but two hotels with ground-floor saloons on Irish Hill, one of them directly behind McManus Union Hotel. To add insult to injury, the Welshes were staunch Democrats. Their brazen affront to ‘His Royal Highness’ (as he was referred to in the press) ignited a bitter, violent rivalry that was known across San Francisco, and eventually dubbed ‘The Blue Mud Wars’ (named for the condition of Irish Hill Streets after a rain, where their street fights raged). The threats of bodily harm (and more actual bodily harm) perpetrated by both sides, in addition to arson, thefts, and attempted murders, were reported regularly in the newspapers. The war went on for several years, its final battle taking place in 1892. The foes and their supporters fought it out in the streets, knee-deep in the mud, wielding knives and clubs, and in at least one case, a gun. By the time the policemen of the Potrero Station arrived, Frank McManus had fired his gun at Thomas at point blank range, and missed.

And so, after years of unpunished criminal activity (extortion, bribery, public drunkenness, vandalism, battery, assault with a deadly weapon, and even vulgar language), the ‘King of the Potrero’ was finally dethroned. In 1894, when his favorite brother, Cornelius, was stabbed and killed in a bar fight at the Union Hotel, Frank McManus slowly drank himself to death. He died two years later at the age of 57.

Most Irish Hill residents were hard working, law-abiding citizens. They worked there as laborers at the Iron Works, shipbuilders, carpenters, welders, cooks, clerks, waiters, dressmakers, butchers, grocers and blacksmiths. There was widow Jane Jackson, who owned and operated a successful bakery on Irish Hill from 1885-1891. When her shop was destroyed in the 1887 fire, she moved across the street; eventually she opened a second bakery in another part of town. Patrick McCormick lived and worked on Irish Hill almost as long as Irish Hill existed. He started off as a ‘ship carpenter,’ in the mid-1870s opened his own grocery and liquor store, and eventually purchased several large corner lots. He was the proprietor of the Nevada House (which can be seen in the panorama photograph) at the corner of 20th and Illinois Street from 1905 until 1910.

This 1918 photo, courtesy San Francisco Maritime Research Center, was taken from the north side of 20th Street, mid-block, near the Bethlehem Steel Powerhouse. Twentieth Street was the main business district of Irish Hill. These buildings featured a saloon and restaurant on the ground floor, and hotel/boarding rooms upstairs. Business like these were common on Irish Hill and catered to the mostly-single men who worked at various shipyard industries. Note the Bethlehem Steel Machine Shop (1883) on the left, which is currently being rehabilitated as part of Pier 70's redevelopment.

Photo: San Francisco National Maritime Museum

The death knells began pealing for Irish Hill as early as 1897, when the Union Iron Works acquired a 200’x200’ parcel of the hill just south of their foundry and began grading it to expand their operations. They continued chopping away at the hill until 1899, in order to build additional structures. The City may have funded this as part of a plan to extend Sixth Street from Channel Bridge to Kentucky (3rd) Street. The extension was never built. Then, in 1918, flush with cash from their prolific shipbuilding for WW1, Bethlehem Steel (formerly Union Iron Works) bought up the lots at 20th Street between Michigan and Illinois Streets to build a $130,000 concrete foundry building. Like the Sixth Street extension, the foundry building was never built. The land was used as a parking lot, looking very much as it looks today. The war effort for the Second World War necessitated more of the decimation of Irish Hill, this time on a larger scale. Millions of cubic yards of rock and soil were blasted and hauled away from the area surrounding 22nd, Street between Georgia and Maryland Streets (where the bare knuckle boxing matches were held in the 1880s). One of Pier 70’s warehouses, Building 12, and its parking lot, built in 1941, sit on excavated land that is actually 90’ below the intersection of 22nd (Sierra) Georgia Streets, one block from where Mike Boyles’ Steam Beer Dump hosted the bare-knuckle boxing matches on Saturday nights.

How ironic that the industry that brought about the settlement of Irish Hill also brought about its destruction.

Irish Hill can never rise out of the ashes, like the phoenix on our City’s flag, but as part of the Union Iron Works Historical District, it can be preserved by the developers of Pier 70, so that the history of Irish Hill, the only visible reminder of whose existence is a lonely clump of rock topped with wild fennel, can be shared with all San Franciscans.

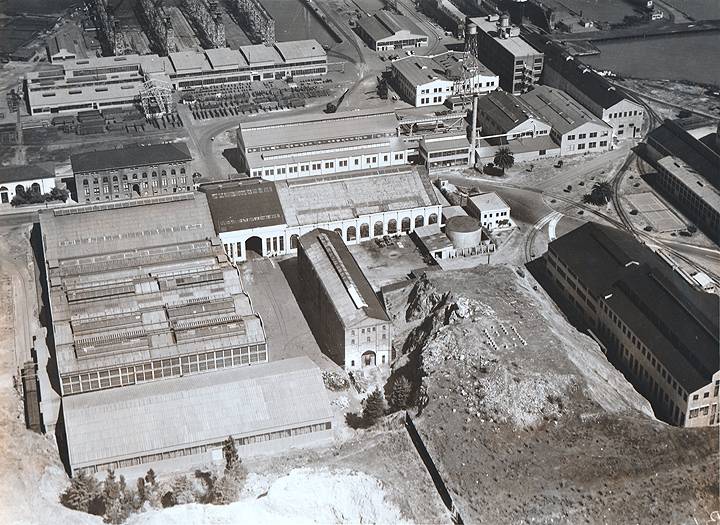

'This 1937 aerial shot of Pier 70 shows the last portion of Irish Hill before it was leveled (lower right). This mass of the hill was at least 10 times larger than the portion of Irish Hill that remains today (barely visible on the lower left). Once leveled, from a 90' elevation to just above sea level, this area of flat land (along with the land created by the razing of the buildings to the immediate left and the immediate right of the hill) became home to Bethlehem Steel's Building 2 (a warehouse) and Building 16 (a plate shop). This expansion in 1941 was necessary for Bethlehem Steel's increased production for WWII. Both Building 2 and Building 16 are still standing.

Photo: courtesy Pier70.org.