SAN FRANCISCO'S ROLE IN THE WAR IN THE PHILIPPINES

Historical Essay

by James Sobredo

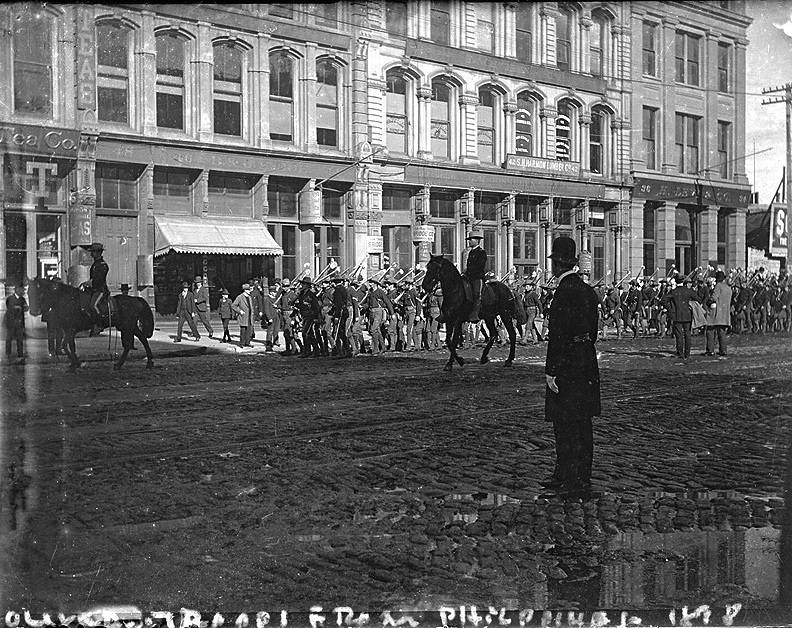

Parade of troops returning from the Philippines, marching on Market Street in San Francisco, c. 1898.

Photo: Online Archive of California

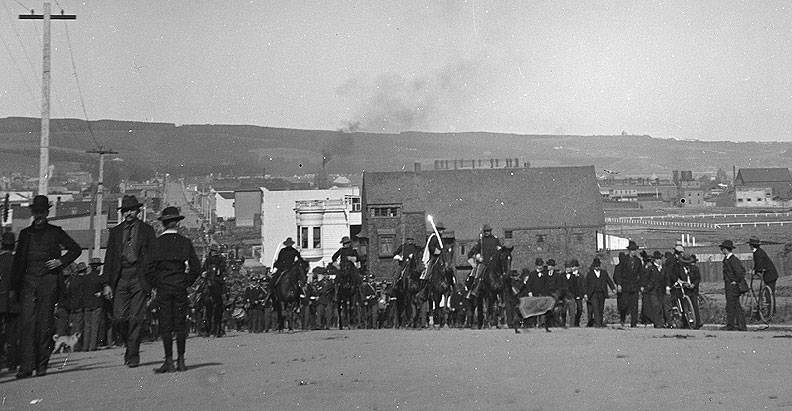

Military expedition leaving for the Philippines during "Spanish-American War" in 1898, seen here on Lombard near Van Ness, looking west.

Photo: Alice Burr, via California Historical Society

President McKinley addresses troops returned from the Philippines in the Presidio in 1901.

Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco, CA

San Francisco's Presidio played a crucial role in America's rise to becoming a world superpower. On May 1, 1898, Commodore George Dewey and the U.S. Navy's Third Asiatic Squadron engaged the Spanish naval fleet in Manila Bay. This battle signalled America's first military action in the Spanish-American War. Overnight, Dewey's military triumph transformed him into a national hero, and a monument in the middle of Union Square in downtown San Francisco stands in commemoration of Dewey's naval victory in the Philippines.

Union Square Monument dedicated to Admiral Dewey at Manila.

This monument, which used to be at Market and Van Ness, now sits at Dolores and Market. It is dedicated to the "California Volunteers" who went to the Philippines during the US-Philippine War 1898-1903, when they participated in the slaughter of at least a half million Filipinos.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Dewey's naval victory did not, however, immediately mean an American victory in the Philippines. Manila's Intramuros fortress was still occupied by the Spaniards, and, throughout the country the rest of the Spanish armed forces were quickly being overwhelmed by Philippine nationalist forces. Dewey and the U.S. Naval fleet were anchored in the middle of Manila Bay waiting for the arrival of reinforcements: ground troops for a land invasion of the Philippines.

San Francisco's Presidio would be the training center and embarkation point for the U.S. Army's land invasion of the Philippines. The invasion force was under the command of U.S. Army General Wesley Merritt. In May of 1898, over 10,000 "volunteers" would come from the western and middle-west states to train in the Presidio. Like the 1991 Persian Gulf War, the Spanish-American War was so popular that a draft was not needed!

Camp Merriam was hastily erected on the southern end of the Presidio. Made of canvas tents, the Camp processed and trained recruits who enlisted for the War. In some cases, entire regiments would show up, for instance, the Tennessee Volunteers. Soon, with thousands of people living in a constricted place, the campgrounds became an unsanitary muddy mess. Morale and enthusiasm for the war was high, and through careless discharging of firearms, some soldiers were killed even before they saw the Philippines.

When the Treaty of Paris was signed on 10 December 1898, which formally ended the Spanish-American War, Gen. Merritt's forces had already captured Manila in a staged battle between the Americans and Spaniards. The Spaniards could not countenance the prospect of surrendering to Filipino rebel forces, so they collaborated with the Americans in a famous "Mock Battle"!

The rest of the Philippines, however, was under the control of Filipino rebels. Led by Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo, Filipinos has established a provisional government, elected a Congress, and drafted a constitution -- which, ironically enough, was based on the U.S. Constitution. At the signing of the peace treaty, a peculiar situation existed in the Philippines: the American forces in Manila were surrounded by Gen. Aguinaldo's army, and the rest of the Philippines was controlled by Filipino nationalist rebels.

Nonetheless, the United States formally claimed the Philippines as a "U.S. Territory" under the 1898 Treaty of Paris, and paid Spain $20 million as an indemnity for the war. A few months later, shooting would erupt between American and Filipino soldiers. The United States called it the "Philippine Insurrection," but, to Filipinos, the "Philippine-American War" was another war of independence against another imperialist nation. It lasted from 1899 to 1902, when Gen. Aguinaldo was captured by Col. Frederick Funston, but sporadic fighting continued in the countryside until 1904. American historians acknowledge that the war cost Filipinos over 200,000 lives, most of whom were innocent civilians. Filipino nationalist historians, however, claim a much higher number. Citing figures given in the New York Times that over 300,000 civilians alone were killed in U.S. military campaigns in Samar Island in the Visayas, Filipino historians claim that the casualties were closer to 1 million. It was in the Philippines that "concentration camps" and "free fire zones" would be practiced by the U.S. military, which led to outbreaks of starvation and diseases, killing thousands of Filipino civilians.

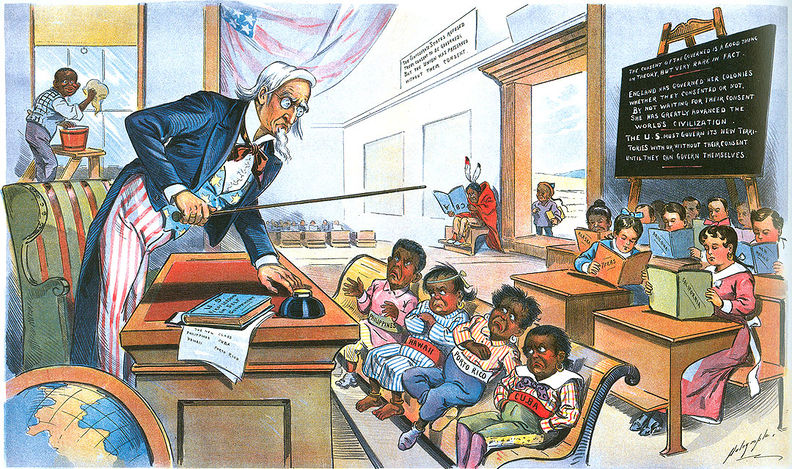

School Begins: "Uncle Sam (to his new class in Civilization)—Now, children, you've got to learn these lessons whether you want to or not! But just take a look at the class ahead of you, and remember that, in a little while, you will feel glad to be here as they are. (artist: Louis Dalrymple, Puck, New, York, Jan. 25, 1899)

During the brief Spanish-American War and the longer Philippine-American War, the Presidio also served as a military hospital and rehabilitation center for soldiers wounded in the War. Over 125,000 soldiers fought in the war in the Philippines. It would cost the United States billions of dollars and over 4,234 American lives. Today, there is a Spanish-American War section in the Presidio Museum, and there are very few reminders of the existence of Camp Merriam. The monument to Commodore George Dewey still stands in the middle of Union Square, surrounded by Macy's, Nieman Marcus, the Hilton Hotel, and other fashionable icons of American corporate capitalism. And near Daly City, the Bay Area's modern-day "Filipinotown," Col. Frederick Funston, a villain in the Philippines, has a National Park named in his honor. Fort Funston National Park sits on a beautiful cliff overlooking the sand and surf of the Pacific Ocean, and is a popular park for families, dog lovers, and hang-glider enthusiasts.

--James Sobredo, April 1996