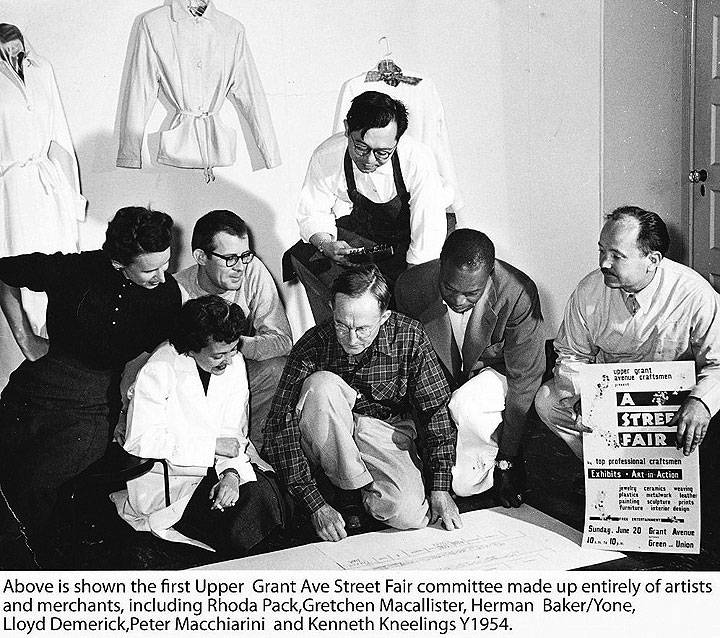

Upper Grant Avenue Street Fair--An Oral History

Historical Essay

by Romalyn Schmaltz, originally published in The Semaphore #215, Autumn 2016

(l to r): Mary Erckenbrack, Peter Macchiarini, and Judy Weld, pose with a street fair sign on June 22, 1956. The group, Judy with watering can in hand, gathered on Union Street to promote THD's tree planting campaign. Mary and Peter were artists, and Judy was Miss San Francisco 1956. The sign reads "Upper Grant Avenue craftsmen present their third annual fair--exhibits, art in action."

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

This summer, North Beach celebrated the 62nd Annual North Beach Festival with hundreds of vendors lining Grant Avenue, Vallejo and Green Streets, Columbus Avenue, and Washington Square Park. Nowadays, we think of this as a North Beach weekend event, but it was born as a small fair on upper Grant Avenue. Many of the Telegraph Hill Dwellers’ board members volunteered at THD’s Green Street booth, and we got to talking about the Festival’s origins, and whether its future iterations might be able to revisit its roots.

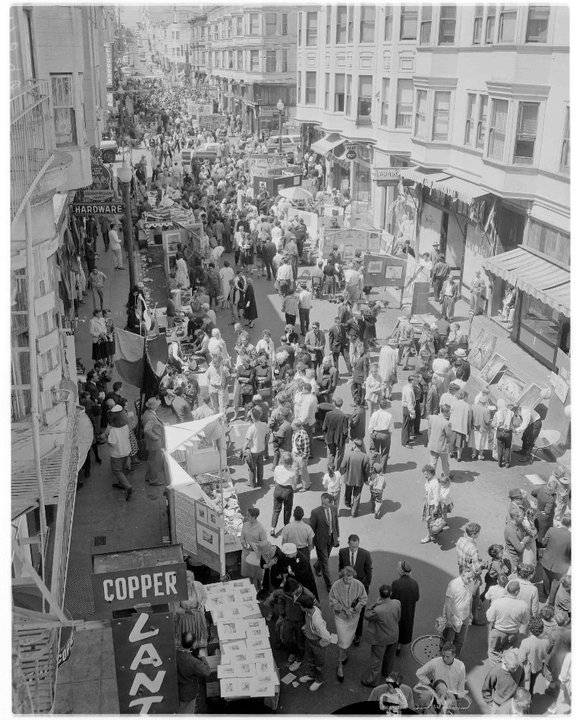

Grant Avenue Street Fair, or open air art show, June 18, 1960.

Photo: San Francisco Examiner archives, via Bancroft Library

Daniel Macchiarini is the second-generation North Beach artist and historian at his old-world yet avant-garde shop, Macchiarini Creative Design, at 1544 Grant Avenue. He welcomes discussions about the real, textural history of the neighborhood when you drop in at his shop. As his family was central to the Fair’s origins, Danny easily launches into the oral history of the North Beach Street Fair at once.

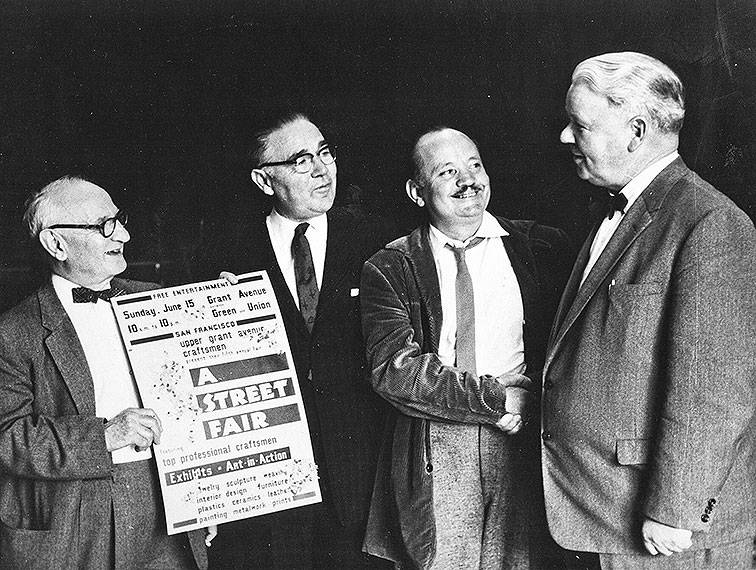

City Supervisors and supporters of the original Upper Grant Avenue Street Fair.

Photo: courtesy Dan Macchiarini

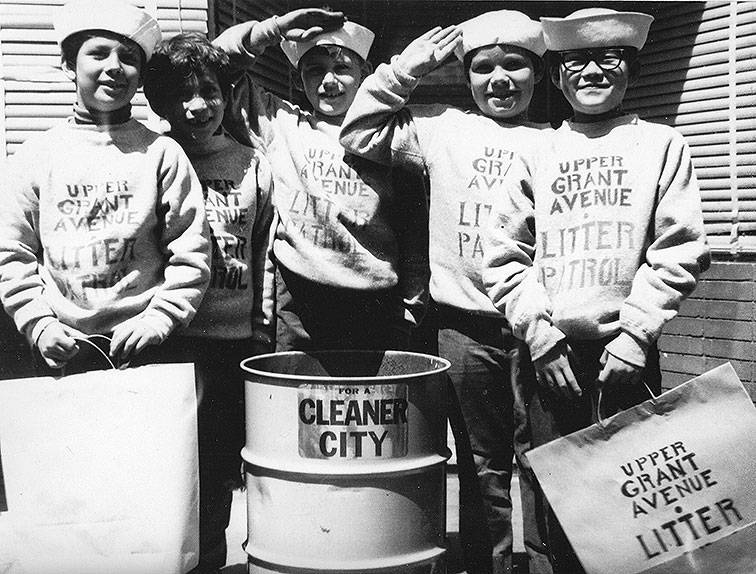

Young neighborhood stewards clean up at the Upper Grant Avenue Street Fair.

Photo: courtesy Dan Macchiarini

Sidewalk chalk era and patrons at an early Fair, c. 1970s.

Photo: courtesy Dan Macchiarini

A local weaving vendor at an early Fair.

Photo: courtesy Dan Macchiarini

“The idea of a street fair was always a crackpot idea of artists, and it actually started with Benny Bufano and my father (sculptor Beniamino Benevenuto Bufano and sculptor/jeweler Peter Macchiarini) in the late 30s, early 40s, before the war broke out. They’d always had this idea that we should just take part of the street and close it to traffic, but the idea of closing a thoroughfare, even then, was considered a truly crackpot idea.

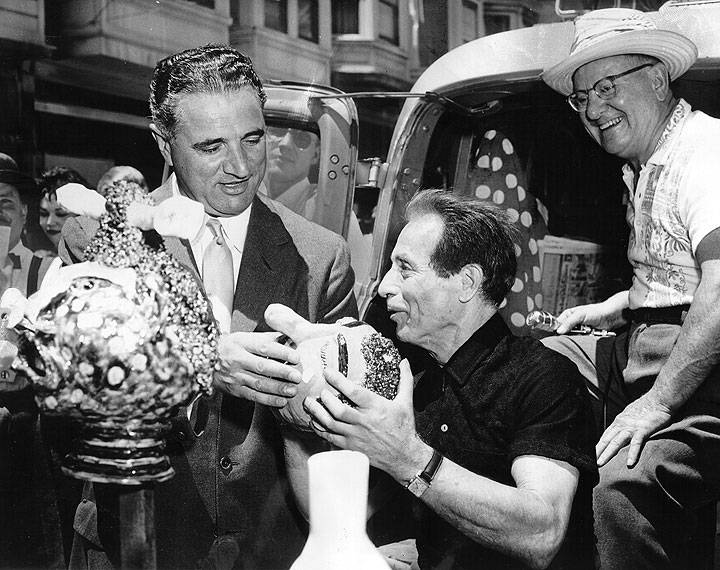

June 16, 1958: Sculptor Benny Bufano and Mayor George Christopher, a surprise visitor, inspect some of the works of art at the upper Grant Avenue Fair yesterday. The Fair, which had to fight for its existence in the face of opposition from both police and fire departments, drew some 35,000 visitors. Works of some 70 artists were displayed.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

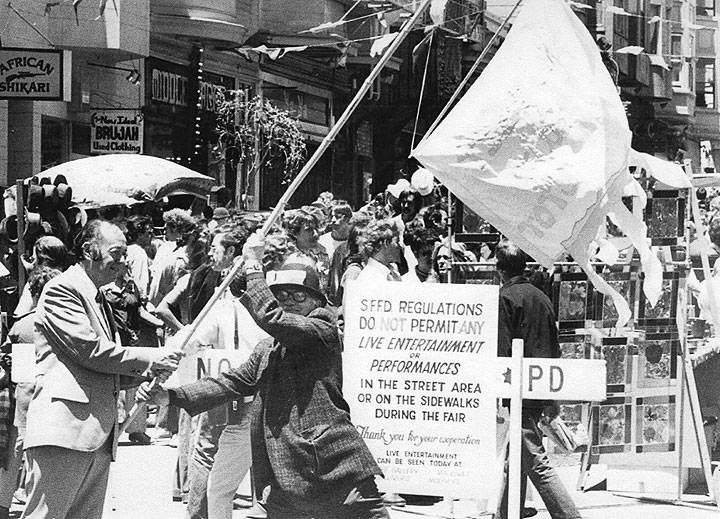

“It was never conceived of as a ‘festival.’ It was not a fair in the park, it was a street fair, conceived of as one day, Father’s Day, and it went from 10 AM to 10 PM. It was a huge success, even though they had no way of knowing how to do this. They had never closed a street completely, not even for big parades. This proposal was extremely new, to only allow emergency vehicles if necessary. So it had to go to the Board of Supervisors for a vote. There was no ISCOTT [Interdepartmental Staff Committee on Traffic and Transportation] then, and it was only the next year that they formed the Police, Fire and Safety Committee, but this was the precedent-setter. It passed the BOS by one vote, and the reason they voted for it was because at this time there was a newly formed residents’ organization on Telegraph Hill called the Telegraph Hill Dwellers, and my father was very close to them, and a lot of the artists who lived on the hill that time were instrumental in the formation of this group, including Bufano. The Telegraph Hill Dwellers have always been an essential part of the Fair’s backbone.

“The great thing about it was that there was no food and no booze in the street. What happened instead was that the little merchants put tables out on the sidewalk for people to sit at, and then the local vendors were able to take in the commerce, so it directly benefited local merchants. It was a symbiotic relationship between the artists in the street and the local merchants. There were a tremendous amount of artists on just those three blocks.

Photo: courtesy Dan Macchiarini

State Senator Milton Marks raising the Street Flag with Upper Grant Avenue Street Fair Director Peter Macchiarini, 1971.

Photo: courtesy Dan Macchiarini

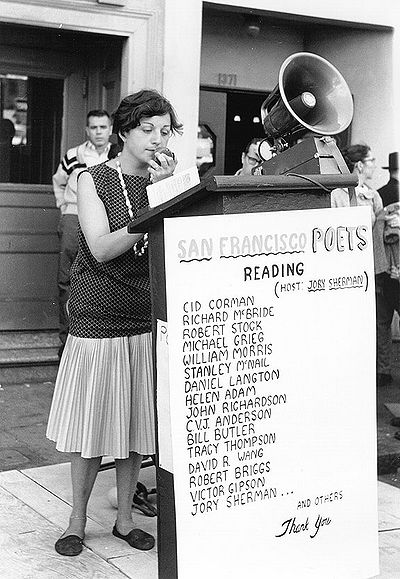

“It was a tremendous success! We got excellent reviews and write-ups, such as from Herb Caen, who said, “This has to become a San Francisco institution!” It took until 1959 for it to really take hold, and it kind-of smoothed out. At its height, in the seventies, it attracted over 200 merchants, mainly artists, from all over the world—potters from Japan, weavers from Germany—and it was extremely affordable. You could buy two spaces—the equivalent of 12 feet—along the curb for $30 for two days, and that would be the equivalent of maybe $100 today, so it was accessible. My father and mother formed a coalition with other artists called The Upper Grant Avenue Artists and Merchants Association (UGAAMA).

“My mother was UGAAMA’s first treasurer, and she figured out that if you made just enough money on it, and spent it all on the community, even to do things like security, which locals like the Telegraph Hill Dwellers did, that it would basically zero out the amount of money so that all you would have left over was the seed money to hold the event again the next year. This prevented everyone from starting fights over money. The object was not to make money for the festival itself, or its organizers. The object was to share North Beach art and culture with the world, and feature great world artists who would share with us. So there was much less chance of corruption or graft.

“It was a direct sum of benefits: it was a boon for the community, the local restauranteurs, the merchants, and the local residents. The thing to keep in mind was that because of its huge success, it became the progenitor and the template for every street fair in this country at that time. We were the mold.

Ruth Weiss reads at the Grant Avenue Fair in 1960.

Photo: C.R. Snyder

“Then the city government got wise to how much money there was in this and started dipping their hands into the pot of money, so a space that cost $15 now would cost hundreds of dollars, saying, ‘Oh, we need to pay our police overtime,’ so it became a kind of legal extortion, a graft machine. And then the insurance companies wanted a piece of the pie. So with this new, falsely created complexity, the merchants suddenly seemed to have little choice but to bring in corporate sponsors and organizations that did street fairs. My mother had actually made this incredible pamphlet called ‘How to Make a Street Fair,’ as a blueprint, with correspondence, meeting minutes, and she basically handed them the prototype. Then came all the corporations, like Apple and Chevy. What does Chevy have to do with North Beach?”

Mid-1970s Upper Grant Avenue Street Fair street crowd scene.

Photo: courtesy Dan Macchiarini

This, Macchiarini insists, runs counter not just to the spirit but to the whole methodology of the original street fair, which often invited inebriated patrons to work off their infractions, rather than just threw them in the drunk tank. “Huge vats,” the size of kegs but filled with coffee, were offered to the hyper-Dionysians in the crowd, who helped clean up the fair and assisted with the fray. It was, in Macchiarinni’s estimation, another way in which the neighborhood took care of its own while giving back to the greater community experience.

North Beach Business Association president Fady Zoubi, who oversaw some of the planning for this year’s event, feels part of the problem consists of merchants’ dwindling interest in the Fair/Festival. Many seem to feel the event doesn’t represent the character of the neighborhood anymore, and if anything, it’s a financial burden. “I literally went knocking on every neighborhood business’s door, and no one wanted to have a table or a booth, even at a discounted, local price. They just don’t see the point.” Zoubi went on to say that he hopes the coming year will include outreach to these local merchants, enticing them to stake their claim in the 2017 Festival at an affordable price, and return it, if not to its roots on one stretch of Grant Avenue, to a more truly local affair. “There’s very little surplus—the money made is instantly reinvested into next year, with a lot of those funds earmarked for locals, if they’ll take a chance and join us.”

Grant Avenue Street Fair, 2017.

Photo: Chris Carlsson