Chinese Restaurants in the 19th Century

Historical Essay

by Barbara Berglund

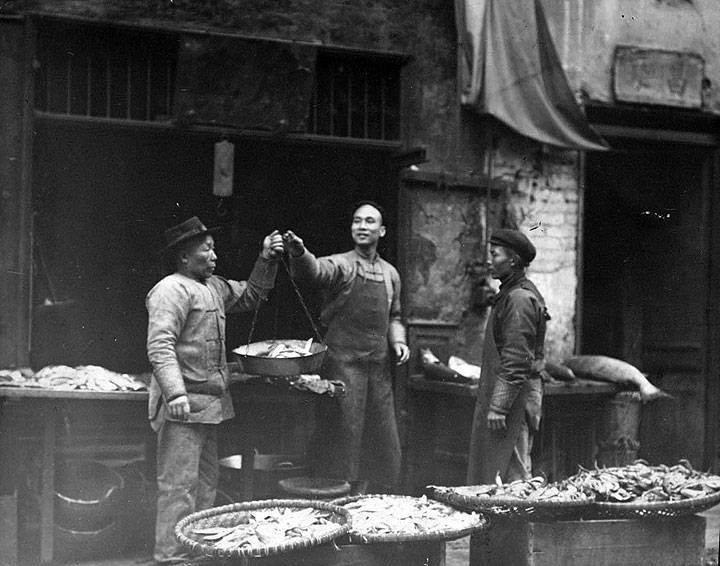

Chinese restaurant interior, 1890s.

Photo: Bancroft Library, BANC-PIC-1985.084-107--ALB

While it might seem a little odd that after an enumeration of the dangerous public health conditions that existed in Chinatown, visitors would then be directed to go there and eat, this was, in many respects, precisely the point. Many accounts tended to stress the strangeness and difference of Chinese food and customs. In doing so, they often further developed the idea of the Chinese as dangerous alien contaminants by representing the Chinese diet as filled with polluted foods—or at least those unpalatable to Anglo-American tastes. In this configuration the Chinese were literally what they ate. "They eat things," Joseph Carey told readers of his guide, "which would be most repulsive to the epicurean taste of the Anglo-Saxon. Even lizards and rats and young dogs they will not refuse." Reverend Otis Gibson noted that many Chinese dishes "taste of rancid oil or strong butter," and local writer Josephine Clifford reported to her readers that while she did not want to "say anything mean against the Chinese" she did believe that "the funny little things…at the bottom of a deep earthen jar were rat's tails skinned." Both Carey and Clifford also stressed that appearances could be deceiving and that tourists, if they were not careful, might be misled into consuming polluted foods. Clifford, for example, rather incongruously noted that despite the supposedly unsavory products from which they were made, various Chinese edibles "came out as tempting morsels, square, round, diamond-shaped, octagonal, all covered with coating and icing in gay colors, and so tastefully laid out that had we seen them at a confectioner's on Market or Kearny street, we could not have resisted the wish to devour them." Nevertheless, while they may have been forewarned to the point of being terrified by the time they got there, tourists flocked to Chinatown's restaurants. As Disturnell's Strangers' Guide succinctly put it, Chinese restaurants were "often visited out of curiosity by white persons."(26)

A tourist could engage in several different kinds of activities, involving varying levels of participation, when it came to visiting a Chinese restaurant. Many tourists, like E.G.H., exercised caution and limited their consumption to tea and sweetmeats—"some small bean-meal cookies, a saucer of lichee nut, some salted almonds… candied strips of cocoanut, melon-rind and like delicacies"—which represented a sort of middle-ground between actually eating a full meal and simply watching Chinese people eat, two other popular alternatives. This allowed tourists to partake of some food and drink and to observe a tea-making process that—given how frequently it was described and commented upon—they found fascinating in its elaborateness. They also generally found the tea produced by this ritual to be delicious. As E.G.H. explained it, a waiter arrived table-side with "a large teacup on a carved wooden stand, with a saucer covering it" as well as a "smaller cup without a saucer" for each person. The larger cup was "filled with dry tea leaves" over which the waiter poured boiling water and after allowing it to steep "for a few seconds," "he dexterously poured the liquid off into the smaller cup, and it was ready for drinking." Yet even in this setting some tourists evinced a certain wariness about the strangeness and difference of the Chinese that they were experiencing through their foodways, even when they responded positively to the experience as a whole as well as to the items consumed. When Will Brooks, for example, related requesting the "boy" to bring him and his party "some tea and sweetmeats" he added that, "If he brings us cakes, we will not kill him; but we will not eat the cakes, lest they kill us." While Brooks might have stayed away from the cakes, he thoroughly enjoyed other aspects of the Chinese fare he tried, concluding that "in the preparation of ginger chow-chow, candied and pickled fruits, the Chinaman is a signal success… They all taste good, and may be indulged in without much fear of after consequences."(27)

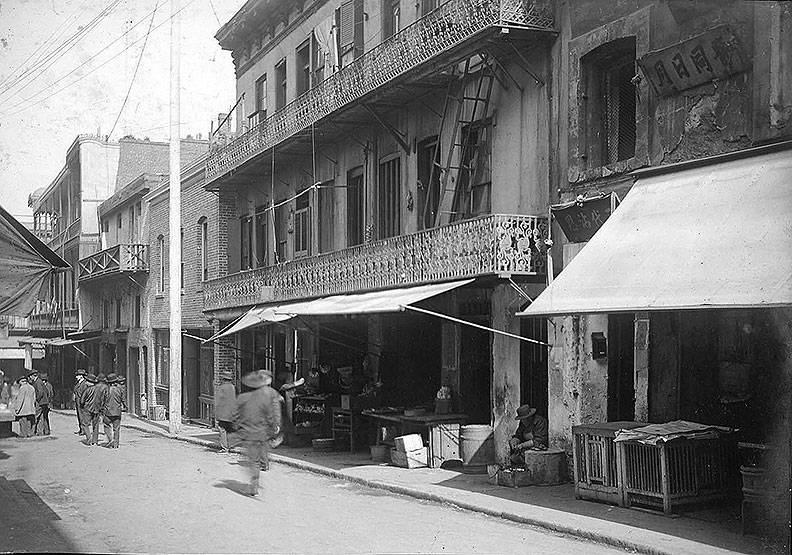

Chinese fish mongers, c. 1900.

Photo: Bancroft Library, BANC-PIC-1985.084-125--ALB

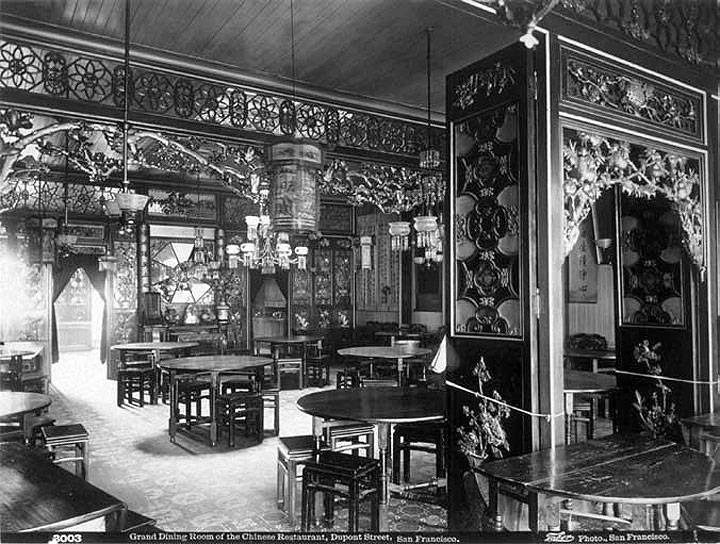

Chinatown's Fish Alley, c. 1890s.

Photo: Online Archive of California

More adventurous tourists went beyond just having tea and sweetmeats and partook of a full meal in a Chinese restaurant. Mabel Craft—a local journalist, fiction writer, and collaborator with Chinatown photographer Arnold Genthe—who described Chinese cuisine as "appetizing after you have overcome your first repugnance," told readers that "if you want a regular Chinese dinner and give notice, a wonderful meal will be prepared." She cautioned, however, that "no one should try it except those of good digestion, for at first it is just a little trying" since the menu included such unfamiliar items as "varnished pig, shark's fins, Bird's nest soup, pickled duck's head, tea, and ShamShu or rice brandy." For these braver few, it was not just the food that would present a challenge but unfamiliar rules of etiquette as well. Reverend Otis Gibson provided his readers with some practical tips and general information to aid in navigating a meal at a Chinese restaurant. "The principal dishes," he told them, "are prepared and placed on the table within easy reach of all. Then each one drives his own chopsticks into the common dish and carries a piece to his mouth. This requires considerable skill and practice. Americans generally find 'many a slip between the cup and the lip.'" "If you get a bone in your mouth after getting all the meat off," he added, "just turn your head and drop the bone on the floor." For the less adept, Gibson noted, the "high toned restaurants" that tourists frequented also kept on hand "knives, forks, plates, table-cloths, and napkins."(28)

Gibson also related to his readers his own experience of dining in a Chinese restaurant with out-of-town visitors—an experience familiar to many San Franciscans before and since. "In company with the Rev. Dr. Newman, Mrs. Newman, and Rev. Dr. Sutherland, of Washington City, and Dr. J. T. M'Lean, of San Francisco," he explained, "I once took a Chinese dinner at the restaurant on Jackson Street." He then described how members of his very respectable party liked their meal and gave some hint as to how each approached the novel event. "Dr. Newman took hold and ate like a hungry man, and when I thought he must be about filled, he astonished me by saying that the meats were excellent, and were it not that he had to deliver a lecture that evening, he would take hold and eat a good hardy dinner. Dr. Sutherland did not seem to relish things quite so well." His description that followed of Mrs. Newman's flexibility and resourcefulness was particularly striking given that middle-class women were so strongly associated with upholding proper etiquette. "Mrs. Newman," he wrote, "relishing some of the meats, and failing to get the pieces to her mouth with the chopsticks, wisely threw aside all conventional notions, used her fingers instead of chopsticks and, as the Californians would say, 'ate a square meal.' "(29)

Gibson's position as a Chinatown missionary certainly gave him unique insights into the neighborhood but his taking of a meal at a Chinese restaurant did not, by any means, make him an exceptional San Franciscan. During the gold rush, before there was even a specific area known as Chinatown, Chinese restaurants attracted wide patronage. In later years, locals not only stopped in for tea and sweetmeats as well as the occasional meal but Chinese elites also frequently used the occasion of a Chinese banquet to make political alliances with other local elites and officials. Typical attendees included members of the press, the police, lawyers, judges, and politicians. Press coverage of such banquets generally gave them high praise, offering detailed descriptions of the food that was served and noting the lavishness and expense of such affairs. As one account in the Alta in 1864 reported, "The dinner for twenty people consisted of over one hundred dishes and could hardly have cost less than $1,000, and may have cost double that sum." Yet, however favorable the overall reviews, the press also frequently felt compelled to make mention of the fact that some of the food was so strange as to be "not at all gastronomically appreciated by the guests."(30)

Now, if on a symbolic level, the Chinese were what they ate, what did it mean when white visitors to Chinese restaurants ate Chinese food? While not every account went so far as to suggest that rats and dogs were being served at Chinese restaurants, the idea that many strange, unknown, and possibly taboo and polluting things were served up in Chinese cooking was pervasive. Given the fact that among nineteenth-century elites and middle classes, restaurants and public dining were freighted with concerns about social purity and mixture, this was a highly charged arena. Food, food-tastes, and the rituals surrounding the consumption of food in both public and private were intricately connected to, on both material and symbolic levels, the articulation of social hierarchies. For white San Franciscans, eating French food, for example, carried with it the connotation of refinement, taste, and civility, while the eating of Chinese food in Chinese restaurants resonated with very different kinds of social meanings. Eating Chinese food in a Chinese restaurant might have been experienced by some as furthering cultural understanding and softening the social lines that congealed around racial differences. But, even in the best of circumstances or with the best of intentions, taking in or simply observing food that was unfamiliar and sometimes unpalatable also often reinforced the otherness of the Chinese and the whiteness of the patrons that was at the core of anti-Chinese sentiment. In effect, the frequent wariness—if not revulsion—with which whites approached consuming Chinese food echoed and reinforced the prevailing distaste for incorporating Chinese immigrants into the American fold.(31)

Grand dining room of the Chinese Restaurant, Dupont Street, one of Chinatown's finer eateries.

Photo: I.W .Taber, photographer. Chinese in California, Ban croft Library, University of California, Berkeley

For visitors to Chinatown who were not adventurous enough to partake of refreshments at one of its restaurants—as well as for some who were but still wanted to see more—the option also existed of experiencing Chinese eateries by observing the ways Chinese people took a meal in them. Given the fact that Chinatown was full of single workingmen who often rented rooms in dormitory-like hotels, it is no wonder that numerous observers commented on the ubiquity of restaurants for ordinary folk. Many of these "cheap cellar places" were somewhat off the beaten path as far as the tourist trade—which gravitated toward the fancier eateries—was concerned and did not have much interest in the practices of merchants who often employed a cook to feed themselves and their staff from small kitchens in the rear of their establishments. William Doxey explained to readers of his guidebook that in the most humble restaurants "under the sidewalks or in basements" there were "wide benches and tables" for eating and "a series of shelves" for sleeping and usually, at the entrance, "a big cauldron steaming and scenting the air with a fishy smell."(32) Josephine Clifford related being led by her police guide into the basement of a house—described as a "respectable place"—which contained "a barber-shop, a restaurant, a pawnbroker's shop, an opium den, and a lodging house." Inside, sitting "at the round table in the restaurant," Clifford encountered "an enormously fat Chinaman busy with his rice and meat." Although this was clearly a space in which Chinese lived, socialized, and conducted business, her guide promptly asked the man to perform for the tourists he had in tow. What transpired next made it clear that while these kinds of excursions might have felt safer for some tourists—as they exempted them from any culinary obligations—it did not require the eating of Chinese food for restaurants and foodways to do racializing work. "'Hello, John,' the captain addressed him; 'let the ladies see you use your chopsticks.' 'All light,' he answered, laughing all over this broad, shining face; 'me eat licee with chopsticks.'" In language that gave the man animalistic qualities and emphasized his barbarous manners, Clifford declared, "Forthwith, he flung the 'licee' into his capacious maw with such rapidity that his cheeks were filled up and stood out like the pouch of a hamster who has been depredating on the nearest corn-crib." She and her group quickly "moved on for fear he should choke eating rice for our entertainment."(33)

While gazing upon Chinese in the "cheap cellar places" gave tourists a firsthand view of the working poor, elite eateries—generally located in upstairs apartments—were another favorite spot of observation that provided a somewhat different view of the Chinese and their environs. Accounts of these places, which were the kinds of restaurants that tourists typically frequented, often stressed the beauty of their appointments-offering a tone of appreciation that stood in contrast to the appraisals of lower-class eateries and the overriding emphasis on the strangeness of Chinese foodways. Charles Keeler—local writer, artist, and naturalist—described one such restaurant he visited as "elegantly furnished with black teak-wood tables and carved chairs, inlaid with mother-of-pearl" and decorated with "carved open work screens." W H. Gleadell recounted a scene in a more upscale Chinese restaurant and offered some insight into the way Chinese patrons reacted to white observers in their midst. He explained that he and his party "were conducted by our guide to a mammoth restaurant." "Attracted by the confused babel of noise proceeding from an upper-room," they made their way in that direction, making sure that they kept close to their guide. They found themselves "in a large square room in the midst of a mixed crowd of Chinese men and women, all chattering and shouting at one and the same time, and busily engaged in their evening meal." Most "were seated round a table, in the centre of which stood a huge bowl" from which "chop sticks were… dipped into and withdrawn from… all corners with rare dispatch." Gleadell and his companions "walked about quite unchallenged, and apparently quite unremarked, without arousing the slightest expression of curiosity or concern." It was, he wrote, "as though our presence were nobody's business but our own." Gleadell, perhaps, expected the Chinese to have viewed him as exotic or threatening as the Chinese were to him. Instead, it was quite possible that white visitors to Chinatown had become such a mundane occurrence that its residents found that it was safer and more convenient to simply avoid or ignore them when they could.(34)

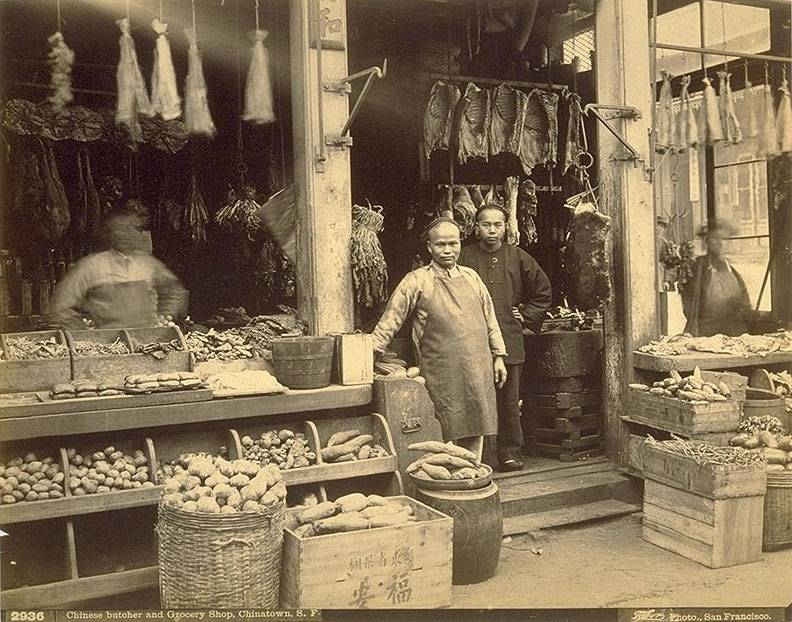

Chinese butcher and grocery store, c. 1890s.

Photo: Online Archive of California

Notes

26. Carey, By the Golden Gate, 196; Gibson, Chinese in America, 71; Josephine Clifford, "Chinatown," Potter's American Monthly (May 1880): 354-364; Doxey, Doxey's Guide to San Francisco, 118; Disturnell’s Strangers' Guide. It is worth noting as well that much of Gibson's description was reprinted in "Chinese in San Francisco," 182. For further description of the polluted quality of Chinese food, see also Ames, "Day in Chinatown," 500; Browne, Trip to California; Kessler, "Evening in Chinatown," 445; and Caldwell, "Picturesque in Chinatown," 657. Brooks, "Fragment of China," 4, also noted the possibilities for deception. Lee, Orientals, 38-39.

27. Craft, "Some Days and Nights in Little China," 102-103; E.G.H., Surprise Land, So; Brooks, "Fragment of China," 3-4. See also, '"China Town' in San Francisco," 52; and Doxey, Doxey's Guide to San Francisco, 115.

28. Craft, "Some Days and Nights in Little China," 102-103. Doxey, Doxey's Guide to San Francisco, 118, also mentioned arranging a meal in advance in suspiciously similar language. Gibson, Chinese in America, 70-71.

29. Gibson, Chinese in America, 71-72.

30. Lloyd, Lights and Shades, 23 I mention these banquets. Daily Alta California, September 20, 1864; San Francisco Examiner, January 28, 1868. See also, for example, the San Francisco Call, March 1, 1896. Two of these banquets in the 1860s, as reported in the local papers, hosted high-ranking members of the police force and law enforcement at one and "members of the press, the Judiciary, the bar, the army" and the fire department at the other. Another in 1896, that feted numerous city officials "at the Hang Fer Low restaurant, 713 Dupont street" was sponsored by "The Tinn Yee Quang Sow Benevolent Association of the Low Quang Chung Chew—a group organized specifically to smooth relations between whites and Chinese.

31. As Mary Douglas has shown, the specific ways people feed their physical bodies disclose and shed light on the needs and fears of the social body. See Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger:An Analysis of the Concepts of Pollution and Taboo (London:Routledge, 1966). See also John Kasson, Rudeness and Civility (New York: Hill and Wang, 1990), 182.

32. "Chinese in San Francisco," 182. This article was paraphrasing from Gibson, Chinese in America, 70. Doxey, Doxey's Guide to San Francisco, 118; Carey, By the Golden Gate, 187. See also Keeler, San Francisco and Thereabout, 62.

33. Clifford, "Chinatown," 354-355.

34. Keeler, San Francisco and Thereabout , 62; Gleadell, "Night Scenes in Chinatown," 379•

Originally published in chapter 3 “Making Race in the City: Chinatown's Tourist Terrain” in Making San Francisco American: Cultural Frontiers in the Urban West, 1846-1906 by Barbara Berglund (University Press of Kansas: Lawrence KS 2007)